Spring 2006 Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kap Community Final Version

COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2020 Photo by User: P199 at Wikimedia Commons Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... 5! 1.0 Introduction and Background .................................................................................................... 6! 1.1 Developing the Community Vision and Mission Statements ................................................. 6! 1.2 Vision Statement ..................................................................................................................... 6! 1.3 Mission Statement .................................................................................................................. 6! 2.0 Communications and Consultation ............................................................................................ 7! 2.1 Steering Committee ................................................................................................................ 8! 2.2 On-line Survey ........................................................................................................................ 8! 2.3 Focus Groups .......................................................................................................................... 9! 2.4 Interviews ............................................................................................................................... 9! 2.5 Public Consultation ............................................................................................................... -

Summer 2015 Vol

Summer 2015 Vol. 42 No. 2 Quarterly Journal of the Wilderness Canoe Association The crew on a beautiful day getting ready to head out on Racine Lake. From L to R: Gary Ataman, Ginger Louws, Larry Hicks, Matt Eberly, Jeff Haymer, Gary James, Mary Perkins, Richard Griffith. Chapleau River 2 013 by Richard Griffith For lovers of whitewater, Chapleau-Nemegosenda River spent the first night at Missinaibi Headwaters Outfitters. Provincial Park, west of Timmins, ON, presents a unique and Racine Lake is huge, and I’m sure that crossing it on a windy interesting loop. The two rivers flow north on their way to day would present a formidable challenge. Fortunately for us, James Bay, and run parallel to each other for about 90 km, starting out in warm weather on Canada Day 2013, it was a until they meet at Kapuskasing Lake. One can paddle down sheet of glass. Calm as it was, it still took a long time to one river and up the other, finishing close to the start, thus cross. minimizing the car shuttle. Good plan. That’s what we When we emerged from the lake, the river narrowed and, thought, but it didn’t quite work out that way. The trip was after some miles, practically disappeared into an almost im - capably led by Gary James. The other participants were Gary penetrable thicket of downed trees. We couldn’t find the cur - Ataman, Mary Perkins, Larry Hicks, Jeff Haymer, Matt rent. We couldn’t find the portage either, though we had a Eberly, Ginger Louws and myself. -

2008 Ontario Hunting Regulations Summary Complete

A MESSAGE from the Government of Ontario unting has long been a popular outdoor activity for thousands of Ontario residents and visitors to the province. Each year, Havid hunters take to the field in pursuit of waterfowl, deer, moose and other quarry. Hunter support is key to the success of Ontario’s wildlife management programs. This can include everything from actively participating in resource management such as habitat improvement projects to responding to harvest surveys. The sustainable management of the province’s wildlife populations allows for the continued expansion of hunting opportunities, where appropriate. This year, the ministry is updating Ontario’s Wild Turkey Management Plan to provide long-term guidance for management of this species as part of southern and central Ontario’s biodiversity. The tremendous success of wild turkey restoration has seen populations thriving in suitable habitats. A fall turkey season has been proposed in numerous Wildlife Management Units (WMUs) in southern Ontario. New spring turkey seasons in three central Ontario WMUs are in place for 2008. ATTENTION NON-RESIDENT HUNTERS A broad review of Ontario’s moose program is now underway, with special emphasis this year on updating the moose policy and Non-resident Outdoors Card population management tools. There will also be preliminary The Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) has discussions on enhancements to the moose draw system this year and embarked on a project to improve the way that more in-depth discussions in early 2009. The goal is to ensure that the hunting and fishing licences are sold, including the province’s moose management program remains modern and world- development of an automated licence system for class and that it responds to environmental changes and societal needs. -

Draft Environmental Report Ivanhoe River

Draft Environmental Report Ivanhoe River - The Chute and Third Falls Hydroelectric Generating Station Projects Revised May 2013 The Chute and Third Falls Draft Environmental Report May 2013 Insert “Foreword” i The Chute and Third Falls Draft Environmental Report May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Waterpower in Ontario ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Introduction to Project .................................................................................................. 1 1.2.1 Zone of Influence .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Screening Process ........................................................ 4 1.4 Approach to the Environmental Screening Process ........................................................ 5 1.4.1 Legal Framework ................................................................................................... 6 1.4.2 Characterize Local Environment of Proposed Development ................................... 7 1.4.3 Identify Potential Environmental Effects ................................................................. 8 1.4.4 Identify Required Mitigation, Monitoring or Additional Investigations ................... 8 1.4.5 Agency and Public Consultation and Aboriginal Communities Engagement ............ 8 2. -

Rails Across Canada

Rails across Canada American Museum of Natural History American Museum of Natural History Rails across Canada On the rails 1 Vancouver-Kamloops • Kamloops-Jasper • Jasper-Edmonton; Edmonton-Winnipeg • Winnipeg-Sudbury • Sudbury-Montreal Canadian basics 37 Government • Population • Language • Time zones • Metric system • Media • Taxes • Food • Separatist movement Early Canada 41 Petroglyphs and pictographs • The buffalo jump at Wanuskewin • Ancient and modern indigenous cultures Modern history: Cartier to Chrêtien 49 Chronology • The fur traders: Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company • Railway history: The building of the transcontinental railway; The Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad & Canadian National Railways Index 68 On the rails Jasper Edmonton Kamloops Vancouver Saskatoon Winnipeg Thunder Bay Montreal Fort Frances Ottawa 2 • Rails across Canada Vancouver to Kamloops Vancouver Contrary to all logic, Vancouver is not on Vancouver Island. Instead, it sits beau- tifully on a mainland peninsula with the ocean before it and the Rockies behind. Its mild climate and inspiring scenery may have contributed a good deal to the laid-back demeanor of its inhabitants, who, Canadians are fond of saying, are more Californian in their outlook than Canadian. Vancouver's view out towards the Pacific is appropriate, for the last two decades "British Columbia is its own ineffable self have seen an extraordinary influx of investment and immigration from the Orient, because it pulls the protective blanket notably Hong Kong. Toronto and the Prairies are much further away, to Van- of the Rockies over its head couver's way of thinking, than are Sydney or Seoul. Vancouver is Canada's third and has no need to look out. -

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2011 Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2011

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2011 Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2011 Edited by: T.A. Scarr1, K.L. Ryall2, and P. Hodge3 1 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Forests Branch, Forest Health & Silviculture Section, Sault Ste. Marie, ON 2 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Great Lakes Forestry Centre, Sault Ste. Marie, ON 3 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Science and Information Branch, Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Section, Sault Ste. Marie, ON © 2012, Queen’s Printer for Ontario For more information on forest health in Ontario visit the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources website: www.ontario.ca/foresthealth You can also visit the Canadian Forest Service website: www.glfc.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca Telephone inquiries can be directed to the Natural Resources Information Centre: English/Français: 1-800-667-1940 Email: [email protected] 52095 ISSN 1913-6164 (print) ISBN 978-1-4435-8489-0 (2011 ed., print) ISSN 1913-617X (online) ISBN 978-1-4435-8490-6 (2011 ed., pdf) Front Cover Photos: Circular photos top to bottom – Diplodia tip blight (W. Byman), Snow damage (S. Young), Emerald ash borer galleries (P.Hodge), Spruce budworm (W. Byman), Forestry workshop in Algonquin Park (P.Hodge). Background: Severe defoliation caused by forest tent caterpillar in Bancroft District (P. Hodge). Banner: Hardwood forest in autumn (P.Hodge). Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2011 Dedication We are proud to dedicate this report to the memory of our friend, colleague, and mentor, Dr. Peter de Groot, 1954-2010. Peter was a long-time supporter of forest health, forest entomology, and forest management in Ontario and Canada. -

Ontario Aboriginal Waterpower Case Studies Ontario 3

Footprints to Follow Ontario Aboriginal Waterpower Case Studies Ontario 3 9 8 6 5 4 2 1 7 Welcome – Aaniin, Boozhoo, Kwey, Tansi, She:kon A core tenet of the Ontario Waterpower Association’s (OWA’s) approach to achieving its objectives has always been working in collaboration with those who have an interest in what we do and how we do it. The OWA has long recognized the importance of positive and productive relationships with Aboriginal organizations. An emergent good news story, particularly in waterpower development, is the growth of the participation of Aboriginal communities. Aboriginal communities have moved from being partners in a waterpower project to the proponent of the project. Waterpower projects are long-term ventures and investments. Projects can take years to bring into service and a decade or more to show a simple payback. However, once in service, a waterpower facility literally lasts forever. Aboriginal partners and proponents taking this long-term view are realizing the multigenerational opportunity to support local capacity development, training, job creation and community growth. Revenue generated from waterpower development can be reinvested in the project to increase the level of ownership, used for other community needs such as housing and infrastructure development, or investing in other economic opportunities. Ontario is fortunate to have significant untapped waterpower potential. In the north in particular realizing this potential will undoubtedly involve the participation of Aboriginal communities. Importantly, a successful industry/First Nations relationship can help establish a business foundation for further expansion. This catalogue aims to share first hand stories in proven Aboriginal communities’ waterpower developments. -

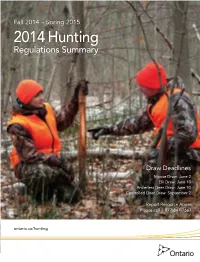

Spring 2015 2014 Hunting Regulations Summary

Fall 2014 – Spring 2015 2014 Hunting Regulations Summary Draw Deadlines Moose Draw: June 2 Elk Draw: June 10 Antlerless Deer Draw: June 30 Controlled Deer Draw: September 2 Report Resource Abuse Please call 1-877-847-7667 ontario.ca/hunting Check out an expanded selection of hunting gear and fi nd a Canadian Tire Pro Shop location near you at canadiantire.ca/proshop © 2014 Canadian Tire Corporation, Limited. All rights reserved. CTR135006TA_SFHG_Rev1.indd 1 13-12-13 3:06 PM Process CyanProcess MagentaProcess YellowProcess Black CLIENT Canadian Tire APPROVALS CTR135006TA_SFHG_Rev1.indd CREATIVE TEAM CREATED 25/10/2013 TRIM 8" x 10.5" CREATIVE Michael S ACCOUNT Rebecca H PROOFREADER TAXI CANADA LTD LIVE 7" x 9.625" MAC ARTIST Chris S PRODUCER Sharon G x2440 495 Wellington Street West PRODUCER Suite 102, Toronto BLEED .25" INSERTION DATE(S) AD NUMBER ON M5V 1E9 STUDIO T: 416 342 8294 COLOURS CYANI MAGENTAI YELLOWI BLACKI F: 416 979 7626 CLIENT / ACCOUNT MANAGER PUBLICATION(S) Saskatchewan Fishing & Hunting Guide MAGAZINE All colours are printed as process match unless indicated otherwise. Please check before use. In spite of our careful checking, errors infrequently occur and we request that you check this proof for accuracy. TAXI’s liability is limited to replacing or correcting the disc from which this proof was generated. We cannot be responsible for your time, film, proofs, stock, or printing loss due to error. SUPERB TECHNOLOGY. SPECTACULAR SUPERIOR OPTICAL PERFORMANCE. NIKON CREATES SCOPES, RANGEFINDERS AND BINOCULARS FOR VIRTUALLY ANY APPLICATION, MAKING IT EASY TO FIND BRILLIANT, IMPECCABLE OPTICS FOR ALL VIEW. -

Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2016

Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2016 Some of the information in this document may not be compatible with assistive technologies. If you need any of the information in an alternate format, please contact [email protected] Forest Health Conditions in Ontario, 2016 Compiled by: • Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Science and Research Branch — Biodiversity and Monitoring Section, Forest Research and Monitoring Section, Natural Resources Information Section © 2017, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Find the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry on-line at: http://www.ontario.ca For more information about forest health in Ontario visit the natural resources website: www.ontario.ca/foresthealth Cette publication hautement spécialisée Forest Health Conditions in Ontario 2016 n’est disponible qu’en anglais conformément au Règlement 671/92, selon lequel il n’est pas obligatoire de la traduire en vertu de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir des renseignements en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère des Richesses naturelles et des Forêts au [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-4868-0306-4 PDF ISSN 1913-617X (online) Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Contributors: Forest health technical specialists (MNRF): • Vance Boudreau • Kirstin Hicks • Vanessa Chaimbrone • Susan McGowan • Rebecca Lidster • Chris McVeety • Mike Francis • Christine Orchard • Lia Fricano • Kyle Webb • Victoria Hard • Cheryl Widdifield Scientific -

E of L. Superior, Nb-Bearing Complexes

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Hunting Regulations Summary

Fall 2018 – spring 2019 2018 HUNTING REGULATIONS SUMMARY 2018 Restricted Sales Period: See page 6 for more details DRAW DEADLINES Moose Draw: May 31 Elk Draw: June 11 Antlerless Deer Draw: July 3 Controlled Deer Draw: August 31 Report Resource Abuse | Please call 1-877-847-7667 ontario.ca/hunting BLEED IT’S IN YOUR CORNER® OFFICE. IT’S IN YOUR NATURE. Let’s face it, hunting isn’t just something you do. It’s who you are. At Cabela’s, we feel the same way. That’s why it’s in our nature to support you with thousands of experts, more than 50 years of experience and every last bit of expertise, so you can treasure this passion for the rest of your days. Barrie – 50 Concert Way 705-735-8900 Ottawa – 3065 Palladium Dr. 613-319-8600 Visit cabelas.ca/stores for more information GET LOST WHERE YOU WANT TO. GET FOUND WHEN YOU NEED TO. The SPOT product family offers peace of mind beyond the boundaries of cellular. Whether you want to check in, alert emergency responders of your GPS location, or monitor your prized possessions, SPOT uses 100% satellite technology to keep you connected to the people and things that matters most. Learn more and see our latest SPOT Products at FindMeSPOT.ca/OntHunt18 SPOT18_OntarioHunting_8x10.5.indd 1 2/26/18 9:15 AM Your source for Firearms, Ammunition and Reloading Supplies 4567 Road 38, Harrowsmith (613) 372-2662 [email protected] www.theammosource.com Table of Contents Table Table of Contents Important Messages for Hunters ......................................................5-7 Maps Map 1 – Southwestern (includes WMUs 79 to 95) ............... -

Smoky Falls Generating Station Was Put in Service in 1931, the Little Long Station in 1963, the Harmon Station in 1965 and the Kipling Station in 1966

Hydro One Networks Inc. 8th Floor, South Tower Tel: (416) 345-5700 483 Bay Street Fax: (416) 345-5870 Toronto, Ontario M5G 2P5 Cell: (416) 258-9383 www.HydroOne.com [email protected] Susan Frank Vice President and Chief Regulatory Officer Regulatory Affairs BY COURIER June 29, 2009 Ms. Kirsten Walli Secretary Ontario Energy Board Suite 2700, 2300 Yonge Street P.O. Box 2319 Toronto, ON. M4P 1E4 Dear Ms. Walli: EB-2009-0078 – Hydro One Networks' Section 92 Bruce – Lower Mattagami Transmission Reinforcement Project– Interrogatory Responses I am attaching three (3) copies of the Hydro One Networks' interrogatory responses to questions from OEB Staff and from the Métis Nation of Ontario. An electronic copy of the responses has been filed using the Board's Regulatory Electronic Submission System (RESS) and the proof of successful submission slip is attached. Sincerely, ORIGINAL SIGNED BY SUSAN FRANK Susan Frank Attach. c. Mr. Jason Madden Filed: June 29, 2009 EB-2009-0078 Page 1 of 2 1 Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) INTERROGATORY #1 List 1 2 3 Interrogatory 4 5 Reference: Exhibit B, Tab 6, Sch. 1, p. 2, lines 13 to 19. 6 7 Preamble: The application states that “An Environmental Assessment Report was 8 submitted to the Ministry of the Environment for the predecessor “Hydroelectric 9 Generating Station Extensions Mattagami River” and approved in 1994. There was no 10 expressed opposition to the project and all concerns were satisfactorily resolved. There 11 are no requirements under the Environmental Assessment Act for the current project; 12 however, Hydro One is undertaking an environmental screening for due diligence 13 purposes.