North Carolina's Digital Preservation Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collecting and Preserving Digital Materials

COLLECTING AND PRESERVING DIGITAL MATERIALS A HOW-TO GUIDE FOR HISTORICAL SOCIETIES BY SOPHIE SHILLING CONTENTS Foreword Preface 1 Introduction 2 Digital material creation Born-digital materials Digitisation 3 Project planning Write a plan Create a workflow Policies and procedures Funding Getting everyone on-board 4 Select Bitstream preservation File formats Image resolution File naming conventions 5 Describe Metadata 6 Ingest Software Digital storage 7 Access and outreach Copyright Culturally sensitive content 8 Community 9 Glossary Bibliography i Foreword FOREWORD How the collection and research landscape has changed!! In 2000 the Federation of Australian Historical Societies commissioned Bronwyn Wilson to prepare a training guide for historical societies on the collection of cultural materials. Its purpose was to advise societies on the need to gather and collect contemporary material of diverse types for the benefit of future generations of researchers. The material that she discussed was essentially in hard copy format, but under the heading of ‘Electronic Media’ Bronwyn included a discussion of video tape, audio tape and the internet. Fast forward to 2018 and we inhabit a very different world because of the digital revolution. Today a very high proportion of the information generated in our technologically-driven society is created and distributed digitally, from emails to publications to images. Increasingly, collecting organisations are making their data available online, so that the modern researcher can achieve much by simply sitting at home on their computer and accessing information via services such as Trove and the increasing body of government and private material that is becoming available on the web. This creates both challenges and opportunities for historical societies. -

Module 8 Wiki Guide

Best Practices for Biomedical Research Data Management Harvard Medical School, The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine Module 8 Wiki Guide Learning Objectives and Outcomes: 1. Emphasize characteristics of long-term data curation and preservation that build on and extend active data management ● It is the purview of permanent archiving and preservation to take over stewardship and ensure that the data do not become technologically obsolete and no longer permanently accessible. ○ The selection of a repository to ensure that certain technical processes are performed routinely and reliably to maintain data integrity ○ Determining the costs and steps necessary to address preservation issues such as technological obsolescence inhibiting data access ○ Consistent, citable access to data and associated contextual records ○ Ensuring that protected data stays protected through repository-governed access control ● Data Management ○ Refers to the handling, manipulation, and retention of data generated within the context of the scientific process ○ Use of this term has become more common as funding agencies require researchers to develop and implement structured plans as part of grant-funded project activities ● Digital Stewardship ○ Contributions to the longevity and usefulness of digital content by its caretakers that may occur within, but often outside of, a formal digital preservation program ○ Encompasses all activities related to the care and management of digital objects over time, and addresses all phases of the digital object lifecycle 2. Distinguish between preservation and curation ● Digital Curation ○ The combination of data curation and digital preservation ○ There tends to be a relatively strong orientation toward authenticity, trustworthiness, and long-term preservation ○ Maintaining and adding value to a trusted body of digital information for future and current use. -

Metadata Demystified: a Guide for Publishers

ISBN 1-880124-59-9 Metadata Demystified: A Guide for Publishers Table of Contents What Metadata Is 1 What Metadata Isn’t 3 XML 3 Identifiers 4 Why Metadata Is Important 6 What Metadata Means to the Publisher 6 What Metadata Means to the Reader 6 Book-Oriented Metadata Practices 8 ONIX 9 Journal-Oriented Metadata Practices 10 ONIX for Serials 10 JWP On the Exchange of Serials Subscription Information 10 CrossRef 11 The Open Archives Initiative 13 Conclusion 13 Where To Go From Here 13 Compendium of Cited Resources 14 About the Authors and Publishers 15 Published by: The Sheridan Press & NISO Press Contributing Editors: Pat Harris, Susan Parente, Kevin Pirkey, Greg Suprock, Mark Witkowski Authors: Amy Brand, Frank Daly, Barbara Meyers Copyright 2003, The Sheridan Press and NISO Press Printed July 2003 Metadata Demystified: A Guide for Publishers This guide presents an overview of evolving classified according to a variety of specific metadata conventions in publishing, as well as functions, such as technical metadata for related initiatives designed to standardize how technical processes, rights metadata for rights metadata is structured and disseminated resolution, and preservation metadata for online. Focusing on strategic rather than digital archiving, this guide focuses on technical considerations in the business of descriptive metadata, or metadata that publishing, this guide offers insight into how characterizes the content itself. book and journal publishers can streamline the various metadata-based operations at work Occurrences of metadata vary tremendously in their companies and leverage that metadata in richness; that is, how much or how little for added exposure through digital media such of the entity being described is actually as the Web. -

2016 Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials

September 2016 Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials Creation of Raster Image Files i Document Information Title Editor Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials: Thomas Rieger Creation of Raster Image Files Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date September 2016 Source Documents Title Editors Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials: Don Williams and Michael Creation of Raster Image Master Files Stelmach http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/guidelines/FADGI_Still_Image- Tech_Guidelines_2010-08-24.pdf Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date August 2010 Title Author s Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Records for Electronic Steven Puglia, Jeffrey Reed, and Access: Creation of Production Master Files – Raster Images Erin Rhodes http://www.archives.gov/preservation/technical/guidelines.pdf U.S. National Archives and Records Administration Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date June 2004 This work is available for worldwide use and reuse under CC0 1.0 Universal. ii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 7 SCOPE .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 THE FADGI STAR SYSTEM ....................................................................................................................... -

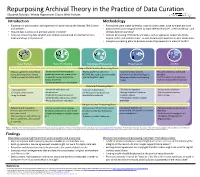

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation Elizabeth Rolando| Wendy Hagenmaier |Susan Wells Parham Introduction Methodology • Expansion of data curation and digital archiving services at the Georgia Tech Library • Process the same digital collection, once by data curator, once by digital archivist and Archives. • Data curation processing informed by OAIS Reference Model1, ICPSR workflow2, and • How do data curation and archival science intersect? UK Data Archive workflow3 • How can comparing data curation and archival science lead to improvements in • Archival processing informed by concepts, such as appraisal, respect des fonds, local workflows and practices? original order, and archival value4, as well documented practices at peer institutions • Compare processing plans to discover areas of agreement and areas of conflict Data Transfer Data Processing Metadata Processing Preservation Access Unique Data Curation Processing Steps -Deposit agreement modeled on -Format transformation policies -Review and enhancement of -Varied retention periods, -Datasets treated as active and institutional repository license guided by reuse over preservation README file, used to accommodate determined by Board of Regents reusable -Funding model for sustainability -Create derivatives to promote diverse depositor needs Retention Schedule and funding -Datasets linked to publications access and re-use model -Bulk or individual file download -Correct erroneous or missing data Common Processing Steps -Data quarantine -Format identification -

Archives First: Digital Preservation Further Investigations Into Digital

Archives First: digital preservation Further investigations into digital preservation for local authorities Viv Cothey * 2020 * Gloucestershire County Council ii Not caring about Archives because you have nothing to archive is no different from saying you don’t care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say. Or that you don’t care about freedom of the press because you don’t like to read. (after Snowden, 2019, p 208) Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily represent those of the institutions to which the author is affiliated. iii iv Executive summary This report is about an investigation into digital preservation by (English) local authorities which was commissioned by the Archives First consortium of eleven local authority record offices or similar memory organisations (Archives). The investigation is partly funded by The National Archives. Archival institutions are uniquely able to serve the public by providing current and future generations with access to authentic unique original records. In the case of local authority Archives these records will include documents related to significant decision making processes and events that bear on individuals and their communities. Archival practice, especially relating to provenance and purposeful preservation, is instrumental in supporting continuing public trust and essential to all of us being able to hold authority to account. The report explains how Archival practice differs from library practice where provenance and purposeful preservation are absent. The current investigation follows an earlier Archives First project in 2016-2017 that investigated local authority digital preservation preparedness. The 2016-2017 investigation revealed that local authority line of business systems in respect of children services, did not support the statutory requirement to retain digital records over the long- term (at least 100 years). -

Applying Library Values to Emerging Technology Decision-Making in the Age of Open Access, Maker Spaces, and the Ever-Changing Library

ACRL Publications in Librarianship No. 72 Applying Library Values to Emerging Technology Decision-Making in the Age of Open Access, Maker Spaces, and the Ever-Changing Library Editors Peter D. Fernandez and Kelly Tilton Association of College and Research Libraries A division of the American Library Association Chicago, Illinois 2018 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences–Permanence of Paper for Print- ed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. ∞ Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress. Copyright ©2018 by the Association of College and Research Libraries. All rights reserved except those which may be granted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Copyright Revision Act of 1976. Printed in the United States of America. 22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................ix Peter Fernandez, Head, LRE Liaison Programs, University of Tennessee Libraries Kelly Tilton, Information Literacy Instruction Librarian, University of Tennessee Libraries Part I Contemplating Library Values Chapter 1. ..........................................................................................................1 The New Technocracy: Positioning Librarianship’s Core Values in Relationship to Technology Is a Much Taller Order Than We Think John Buschman, Dean of University Libraries, Seton Hall University Chapter 2. ........................................................................................................27 -

Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives

Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives! Jefferson Bailey & Maria LaCalle, Internet Archive ALA 2015 | ALCTS PARS | June 27, 2015 @jefferson_bail | [email protected] Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives! Jefferson Bailey & Maria LaCalle, Internet Archive ALA 2015 | ALCTS PARS | June 27, 2015 @jefferson_bail | [email protected] •! We are a non-profit Digital Library & Archive founded in 1996 •! 20+PB unique data: 10PB web, ~8m text, 2m vid, 2m aud, 100K soft, etc •! We work in a former church and it’s awesome •! Developed: Heritrix, Wayback, warcprox, Umbra, NutchWax, ARC format •! Engineers, librarians/archivists, program staff •! https://archive.org/web •! Largest and oldest publicly available web archive in existence •! 485,000,000,000+ URLs (that’s billions) •! Like a billion websites, domain agnostic •! Content in 40+ Languages •! Periodic snapshot; 1b+ URLs per week •! https://archive-it.org/ •! Web archiving service used by 370+ institutions •! 3500+ collection, 10 billion+ URLs •! 49 states and 19 countries •! Libraries, archives, museums, governments, non-profits, etc. •! User groups, Annual Meeting, collaborative and educational projects What is a web archive? •! Web archiving is the process of collecting portions of web content, preserving the collections, and then providing access to the archives - for use and re use. •! A web archive is a collection of archived URLs grouped by theme, event, subject area, or web address. •! A web archive contains as much as possible from the original resources and documents the change over time. It recreates the experience a user would have had if they!had visited the live site on the day it was archived. -

Digital Preservation Metadata for Practitioners Implementing PREMIS

springer.com Computer Science : Computer Applications Dappert, A., Guenther, R.S., Peyrard, S. (Eds.) Digital Preservation Metadata for Practitioners Implementing PREMIS Provides an introduction to fundamental issues related to digital preservation metadata and to its practical use and implementation Bridges the gap between the formal specifications provided in the PREMIS Data Dictionary and specific implementations Addresses the needs of both practitioners and students in Library, Information and Archival Science degree programs or related fields for understanding digital preservation issues This book begins with an introduction to fundamental issues related to digital preservation Springer metadata before proceeding to in-depth coverage of issues concerning its practical use and 1st ed. 2016, XIV, 266 p. 69 implementation. It helps readers to understand which options need to be considered in 1st illus. specifying a digital preservation metadata profile to ensure it matches their individual content edition types, technical infrastructure, and organizational needs. Further, it provides practical guidance and examples, and raises important questions. It does not provide full-fledged implementation solutions, as such solutions can, by definition, only be specific to a given preservation context. Printed book As such, the book effectively bridges the gap between the formal specifications provided in a Hardcover standard, such as the PREMIS Data Dictionary – a de-facto standard that defines the core metadata required by most preservation repositories – and specific implementations.Anybody Printed book who needs to manage digital assets in any form with the intent of preserving them for an Hardcover indefinite period of time will find this book a valuable resource. The PREMIS Data Dictionary ISBN 978-3-319-43761-3 provides a data model consisting of basic entities (objects, agents, events and rights) and basic £ 54,99 | CHF 71,00 | 59,99 € | properties (called “semantic units”) that describe them. -

Digital Preservation Metadata for Practitioners : Implementing Premis Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DIGITAL PRESERVATION METADATA FOR PRACTITIONERS : IMPLEMENTING PREMIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Angela Dappert | 266 pages | 18 Jan 2017 | Springer International Publishing AG | 9783319437613 | English | Cham, Switzerland Digital Preservation Metadata for Practitioners : Implementing PREMIS PDF Book As such, the book effectively bridges the gap between the formal specifications provided in a standard, such as the PREMIS Data Dictionary — a de-facto standard that defines the core metadata required by most preservation repositories — and specific implementations. Skip to content. History The beginnings of a standardized metadata scheme for collections of digital objects can be traced back to , when UC Berkeley and the Digital Library Federation DLF initiated a project to further the concept of digital libraries sharing resources. This chapter presents such challenges and illustrates them with the choices made in the Portico preservation service. Digital preservation metadata profiles vary because of different content types held in the repository, different functions performed on them, different organizational mandates and processes, different policies, different technical platforms, and other reasons. They are using a set of tools, generally open source, to identify, harvest, store, index, make available to end users, and preserve internet content over the long term. I think that to put it simply, the PREMIS Data Dictionary provides a clear guide to what specific information needs to be known about a digital collection and its individual objects in order to best support any digital preservation activities. This is where we can support each other and develop a mutual consensus of best metadata practice for digital preservation sub-domains. By , it had become clear that METS could not only serve as an answer to the interoperability needs associated with sharing digital objects, but that METS is also valuable for preservation purposes. -

PREMIS EC Barcelona March 2009

Digital Preservation Metadata Angela Dappert The British Library, Planets, PREMIS EC Barcelona March 2009 Some of the slides on PREMIS are based on slides by Priscilla Caplan, Florida Center for Library Automation Rebecca Guenther, Library of Congress Brian Lavoie, OCLC Overview Introduction to Digital Preservation Metadata – What is Digital Preservation Metadata – Hands-on Exercise – Case Study: eJournals (1) Preservation Metadata in Practice – Workflow Issues – Tools and Standards – PREMIS Data Dictionary •Overview • Hands-on Exercise • Implementation Issues – Case Study: eJournals (2) Overview Introduction to Digital Preservation Metadata – What is Digital Preservation Metadata – Hands-on Exercise – Case Study: eJournals (1) Preservation Metadata in Practice – Workflow Issues – Tools and Standards – PREMIS Data Dictionary •Overview • Hands-on Exercise • Implementation Issues – Case Study: eJournals (2) Domain What is Digital Preservation Metadata? Metadata = data about data Information that is essential to ensure long-term accessibility of digital resources What is Digital Preservation Metadata? A best guess on the future – little experience with digital objects – uncertain future technical possibilities – uncertain future legal framework in which we will operate Digital objects must be self-descriptive Must be able to exist independently from the systems which were used to create them – XML (machine and human readable) Why do we need new forms of metadata? - Use Cases Supporting New Features MetaD: Semantic Information for the designated -

GVSU Libraries Digital Preservation Policy | 1

Version GVSU 1.0, November Libraries 15th, 2016 Digital Preservation Policy TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. PURPOSE ................................ .......................................................................................................... 2 SECTION 2. MANDATE ................................ ......................................................................................................... 2 SECTION 3. OBJECTIVES ................................ ..................................................................................................... 2 SECTION 4. SCOPE ................................ ................................................................................................................ 3 N COPE ATERIALS 4.1. I -‐S M ................................ ...................................................................................................................... 3 UT OF COPE ATERIALS 4.2. O -‐ -‐S M ................................ ............................................................................................................ 3 SECTION UPPORTED 5. DESIGNATED RESERVATION COMMUNITY EVELS ................................ ......................................................................... 4 4.3. S P L ................................ ............................................................................................. 3 ACULTY TAFF TUDENTS 5.1. GVSU F , S & S ................................ ..........................................................................................