China Antitrust Review 2016 January 25, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Beer Duopoly a Primer for Policymakers and Regulators

Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Marin Institute Report October 2009 Marin Institute Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Executive Summary While the U.S. beer industry has been consolidating at a rapid pace for years, 2008 saw the most dramatic changes in industry history to date. With the creation of two new global corporate entities, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors, how beer is marketed and sold in this country will never be the same. Anheuser-Busch InBev is based in Belgium and largely supported and managed by Brazilian leadership, while MillerCoors is majority-controlled by SABMiller out of London. It is critical for federal and state policymakers, as well as alcohol regulators and control advocates to understand these changes and anticipate forthcoming challenges from this new duopoly. This report describes the two industry players who now control 80 percent of the U.S. beer market, and offers responses to new policy challenges that are likely to negatively impact public health and safety. The new beer duopoly brings tremendous power to ABI and MillerCoors: power that impacts Congress, the Office of the President, federal agencies, and state lawmakers and regulators. Summary of Findings • Beer industry consolidation has resulted in the concentration of corporate power and beer market control in the hands of two beer giants, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors LLC. • The American beer industry is no longer American. Eighty percent of the U.S. beer industry is controlled by one corporation based in Belgium, and another based in England. • The mergers of ABI and MillerCoors occurred within months of each other, and both were approved much quicker than the usual merger process. -

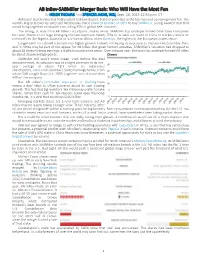

AB Inbev-Sabmiller Merger Bash: Who Will Have the Most Fun by HELEN THOMAS and SPENCER JAKAB, WSJ, Sept

AB InBev-SABMiller Merger Bash: Who Will Have the Most Fun By HELEN THOMAS And SPENCER JAKAB, WSJ, Sept. 16, 2015 12:53 p.m. ET Anheuser-Busch InBev has finally opted to down its pint, but everyone else in the bar may end up having more fun. The world’s largest brewer by sales said Wednesday that it planned to make an offer to buy SABMiller, a long-awaited deal that would bring together companies controlling 30% of global beer volumes. The timing, at least from AB InBev’s standpoint, makes sense. SABMiller has underperformed other beer companies this year, thanks to its huge emerging-markets exposure. Nearly 70% of its sales are made in China or markets reliant on commodities like Nigeria, Australia or sub-Sahran Africa, notes Barclays, the highest in the European staples sector. Longer-term this should translate into higher growth. Indeed, increasing its exposure to markets like Colombia, Peru and in Africa may be part of the appeal for AB InBev. But given current anxieties, SABMiller’s valuation had dropped to about 18 times forecast earnings, a slight discount to the sector. Over the past year, the stock has underperformed AB InBev by about 30 percentage points. SABMiller still won’t come cheap. Even before the deal announcement, its valuation was at a slight premium to its five- year average of about 18.3 times. Its substantial shareholders, Altria and Colombia’s Santo Domingo family, from whom SAB bought Bavaria in 2005, together control more than 40% of the company. But AB InBev’s formidable reputation in slashing costs means a deal helps to offset concerns about its own slowing growth. -

Meet China's Corporates: a Primer

Meet China’s Corporates: A Primer An At-A-Glance Guide to China’s Non-Financial Sectors July 9, 2020 S&P Global (China) Ratings www.spgchinaratings.cn July 9, 2020 Meet China’s Corporates: A Primer July 9, 2020 Contents Beer ..................................................................................................... 3 Car Makers ........................................................................................... 6 Cement ................................................................................................ 9 Chemical Manufacturers .................................................................... 11 Coal ................................................................................................... 13 Commercial Real Estate ..................................................................... 16 Engineering and Construction ............................................................ 18 Flat Panel Display Technology ............................................................ 21 Household Appliances ....................................................................... 23 Liquor ................................................................................................ 25 Online and Mobile Gaming.................................................................. 28 Power Generation ............................................................................... 31 Real Estate Development ................................................................... 34 Semiconductors ................................................................................ -

View Presentation

WORLD BREWING CONGRESS 2016 World Brewing Congress August 13-17, 2016 Prospective demand for malting barley and malt quality for the global brewing industry Sheraton Downtown Denver 159 Peter Watts1, Dr. Yueshu Li1 and Dr. Jessica Yu2 Denver, CO 80202, U.S.A. 1. Canadian Malting Barley Technical Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3C 3G7 2. Tsingtao Brewery Co. Ltd, Qingdao, China 266100 Introduction China Beer Market Evolving Quality Requirements Rapid changes in the world brewing industry including the boom in craft brewing, diversification in In addition to international brewing groups such as Carlsberg and AB-InBev, China Resource Snow Brewery, Tsingtao Brewery, and Beijing Yangjing Beer are dominant Rising beer production in China and the rapid development of craft brewing in the US beer brand/style as well as changing ownership present both challenges and opportunities for the players in China accounting for 71% of beer output. Increasingly Chinese beer manufacturers are strengthening their brand positioning. In 2014 China Resources Snow are driving increased demand for malting barley and malt, and are also shifting quality malting barley industry. In this presentation, trends in global malting and brewing sectors, Breweries produced 107 million hectolitres of Snow beer making it the world’s largest beer brand at 5.4% of the global market. Its total volume is higher than the requirements. In China, brewers are demanding barley with higher grain protein and specifically in China and the United States, and changing quality requirements for malting barley combined volume of Budweiser (4.6 billion liters) and Budlight (5.0 billion liters). Together with Tsingtao Brewery and Beijing Yangjing Beer, these three Chinese brewers very high enzyme potential to compensate for large adjunct incorporation. -

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert's Report In

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert’s Report in relation to the Proposed Demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (ABN 28 050 036 372) 17 March 2011 GRANT SAMUEL & ASSOCIATES LEVEL 6 1 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 T: +61 3 9949 8800 / F: +61 3 99949 8838 www.grantsamuel.com.au Financial Services Guide Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (“Grant Samuel”) holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 240985 authorising it to provide financial product advice on securities and interests in managed investments schemes to wholesale and retail clients. The Corporations Act, 2001 requires Grant Samuel to provide this Financial Services Guide (“FSG”) in connection with its provision of an independent expert’s report (“Report”) which is included in a document (“Disclosure Document”) provided to members by the company or other entity (“Entity”) for which Grant Samuel prepares the Report. Grant Samuel does not accept instructions from retail clients. Grant Samuel provides no financial services directly to retail clients and receives no remuneration from retail clients for financial services. Grant Samuel does not provide any personal retail financial product advice to retail investors nor does it provide market-related advice to retail investors. When providing Reports, Grant Samuel’s client is the Entity to which it provides the Report. Grant Samuel receives its remuneration from the Entity. In respect of the Report in relation to the proposed demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited (“Foster’s”) (“the Foster’s Report”), Grant Samuel will receive a fixed fee of $700,000 plus reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for the preparation of the Report (as stated in Section 8.3 of the Foster’s Report). -

Discussion Materials

BMO Financial Group China’s Role in the Global Food Economy A Look Forward BMO Financial Group in China - Timeline 1818 1961 1996 2003 2004 BMO undertakes first BMO is one of the first BMO is the first BMO becomes a 16.7% BMO is the first FX transaction in western banks to Canadian bank owner of Fullgoal Fund Canadian bank to be support of trade with establish direct licensed for a full- Management, China’s 2nd- licensed by the China China business ties with the service branch in largest mutual fund Banking Regulatory Bank of China Beijing company (increased to Commission to sell 28% in 2004) derivatives in China BMO China Timeline 2005 2005 2006 2008 2010 BMO is the first BMO selected to work BMO opens Shanghai branch officially BMO is the first Canadian bank licensed alongside the BOC, the Investment Banking begins operations Canadian bank to to provide RMB local CITIC and the ICBC as a representative office in incorporate in China currency services to market maker for the new Beijing foreign and local FX trading platform companies in China BMO Financial Group in China – Market Presence Bank of Montreal (China) Co. Ltd. -Office presence since 1983 Beijing -4 Greater China branches and 200 staff ▪ -FX pioneer and government-appointed FX market maker -USD & CNY licenses with national coverage -Active in trade finance -Close relationships with top Chinese banks -Expanded product range with 2010 local incorporation ▪ Shanghai Guangzhou ▪ ▪ Hong Kong Bank of Montreal (China) Co. Ltd is a wholly-owned subsidiary of BMO Financial Group Observations The food industry continues to be one of China’s largest, fastest growing and most important sectors. -

Annual Report 2015 Report Annual

SABMiller plc SABMiller Annual Report 2015 SABMiller plc Annual Report 2015 We are in the beer and soft drinks business. We bring refreshment and sociability to millions of people all over the world who enjoy our drinks. We do business in a way that improves livelihoods and helps build communities. We are passionate about brewing and have a long tradition of craftsmanship, making superb beer from high quality natural ingredients. We are local beer experts. We have more than 200 local beers, from which we have carefully selected and nurtured a range of special regional and global brands. Performance highlights Group net producer revenue1 Revenue3 EBITA4 EBITA margin progression -2% -1% -1% 0basis points 2015: US$26,288m 2015: US$22,130m 2015: US$6,367m 2015: 24.2% 2014: US$26,719m 2014: US$22,311m 2014 5: US$6,460m 2014: 24.2% 2 2 2 +5% +6% +6% +30 basis points2 Beverage volumes Profit before tax Adjusted EPS6 Dividends per share7 +2% 0% -1% +8% 2015: 324m hectolitres 2015: US$4,830m 2015: 239.1 US cents 2015: 113.0 US cents 2014: 318m hectolitres 2014: US$4,823m 2014: 242.0 US cents 2014: 105.0 US cents Water usage (beer)8 Net debt9 Free cash flow10 Total shareholder return11 -6% -27% +26% 121% 2015: 3.3 hl/hl 2015: US$10,465m 2015: US$3,233m Peer median: 85% 2014: 3.5 hl/hl 2014: US$14,303m 2014: US$2,563m 1 Group net producer revenue (NPR) is defined on page 188 and includes the group’s 6 A reconciliation of adjusted earnings to the statutory measure of profit attributable to equity attributable share of associates’ and joint ventures’ net producer revenue of shareholders is provided in note 8 to the consolidated financial statements. -

Sabmiller Plc U.S.$5,000,000,000

Proof3:8.7.09 PROSPECTUS DATED 9 July 2009 SABMiller plc (incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales) (Registered Number 3258416) U.S.$5,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme Under the Euro Medium Term Note Programme described in this Prospectus (the ‘‘Programme’’), SABMiller plc (the ‘‘Issuer’’ or ‘‘SABMiller’’), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Euro Medium Term Notes (the ‘‘Notes’’). The aggregate nominal amount of Notes outstanding will not at any time exceed U.S.$5,000,000,000 (or the equivalent in other currencies). Application has been made to the Financial Services Authority in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (‘‘FSMA’’) (the ‘‘UK Listing Authority’’) for Notes issued under the Programme for the period of 12 months from the date of this Prospectus to be admitted to the official list of the UK Listing Authority (the ‘‘Official List’’) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the ‘‘London Stock Exchange’’) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s Regulated Market (the ‘‘Market’’). References in this Prospectus to Notes being ‘‘listed’’ (and all related references) shall mean that such Notes have been admitted to the Official List and have been admitted to trading on the Market. The Market is a regulated market for the purposes of the Directive 2004/39/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on markets in financial instruments. However, unlisted Notes may be issued pursuant to the Programme. -

Identifying & Addressing Water Risks In

WATER FOOTPRINTING IDENTIFYING & ADDRESSING WATER RISKS IN THE VALUE CHAIN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01 1.0 INTRODUCTION 02 1.1 The water footprint network 02 1.2 Objectives of this report 02 2.0 WATER CHALLENGES & OPPORTUNITIES 04 2.1 Why is water different? 04 2.2 Water–related business risks 06 2.3 SABMiller’s approach to water management 07 2.4 WWF’s view of water footprinting 07 3.0 A BackgROUND TO waTER FOOTPRINTING 08 4.0 CASE STUDY METHODOLOGY 10 4.1 Definitions of water footprint terms 12 4.2 Considering the different aspects of water footprint methodology 12 5.0 CASE STUDIES 14 5.1 SAB Ltd – South Africa 14 5.2 Water pricing in South Africa 15 5.3 Plzensky Prazdroj – Czech Republic 16 5.4 Comparison between the South African and Czech Republic water footprints 17 6.0 CONSIDERING THE BUSINESS IMPLICATIONS 21 6.1 Local action plans 21 6.2 W ater policy 22 6.3 Business value of water footprinting 22 7.0 THE FUTURE FOR WATER FOOTPRINTS 23 7.1 Methodology improvement 23 7.2 Impact analysis 23 7.3 Looking to the future 24 About SABMiller: As one of the world’s largest brewing companies, SABMiller has brewing interests and distribution agreements across six continents. Our wide portfolio of brands includes premium international beers such as Pilsner Urquell, Peroni Nastro Azzurro, Miller Genuine Draft and Grolsch along with leading local brands such as Aguila, Castle, Miller Lite, Snow and Tyskie. Six of our brands are among the top 50 in the world. -

Beverages in Asia

ISSUES FOR RESPONSIBLE INVESTORS BEVERAGES IN ASIA JUNE 2010 Rebecca Lewis Author Rumi M. Morales Editor COMMISSIONED BY Responsible Research is an independent provider of sectoral and thematic Asian environment, Responsible Research is the exclusive partner in Asia for RepRisk, a web-based tool which provides social and governance (ESG) research, targeted at global institutional investors. Many of these fund insights on environmental and social issues that present financial and reputational risks to companies managers and asset owners now find that traditional investment banking reports, financial models and and investment portfolios. The tool enables commercial and investment bankers, asset managers, public information sources can no longer be relied on to cover all risks to earnings and deliver superior and supply chain managers to manage the corresponding risks and to implement effective screening returns. Companies who do not monitor and report on this ‘non-financial’ performance not only risk procedures. financial penalties for non-compliance with stricter regulatory environments but are also denied access to substantial pools of global capital which are managed according to sustainable principles. About the RepRisk® tool Our approach is based on analysis of material ESG factors, which change according to sector and RepRisk® is a web-based tool that allows you to identify and assess the environmental and social market. We provide our clients with local market knowledge of important regulatory landscapes in issues which may present financial, reputational and ethical risks. It is used by investment pro- Asia, along with a fresh perspective on local operational and sectoral issues. We offer an annual fessionals, financial institutions, supply chain managers, multinational corporations and compliance subscription model for our monthly sectoral or thematic reports and give our clients access to the managers, and includes a variety of features enabling clients to monitor risk trends over time, create underlying data. -

Sabmiller Plc Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. PART II OF THIS DOCUMENT COMPRISES AN EXPLANATORY STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SECTION 897 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2006. THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO A TRANSACTION WHICH, IF IMPLEMENTED, WILL RESULT IN THE CANCELLATION OF THE LISTINGS OF SABMILLER SHARES ON THE OFFICIAL LIST OF THE LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE AND THE MAIN BOARD OF THE JOHANNESBURG STOCK EXCHANGE, AND OF TRADING OF SABMILLER SHARES ON THE LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE’S MAIN MARKET FOR LISTED SECURITIES AND ON THE MAIN BOARD OF THE JOHANNESBURG STOCK EXCHANGE. THE SECURITIES PROPOSED TO BE ISSUED PURSUANT TO THE UK SCHEME WILL NOT BE REGISTERED WITH THE SEC UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES. THE APPROVAL OF THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND WALES PROVIDES THE BASIS FOR THE SECURITIES TO BE ISSUED WITHOUT REGISTRATION UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT, IN RELIANCE ON THE EXEMPTION FROM THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE US SECURITIES ACT PROVIDED BY SECTION 3(a)(10). If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own independent advice as soon as possible from your stockbroker, bank, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent professional adviser who, if you are taking advice in the United Kingdom, is appropriately authorised to provide such advice under the United Kingdom Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended), or from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser if you are in a territory outside the United Kingdom. -

The Case for the Global Megabrewer Here at Tufts, Our Beer of Choice Is

Walker Kehoe Consumer Staples Lead Analyst Tufts Financial Group 12/1/2015 The Case for the Global Megabrewer Here at Tufts, our beer of choice is Natural Light—it’s cheap, easy to drink, and tastes marginally better than Keystone. Natural Light, or ‘Natty’ as we call it, is brewed by Anheuser-Busch InBev (BUD), the multinational megabrewer that recently decided to acquire its closest rival SABMiller (SAB). A potential acquisition was announced by AB in mid-September and finalized on November 11th. The nearly $108 billion deal is complex and hard to swallow, which explains why BUD stock traded horizontally between September and November. In the next few paragraphs, we hope to break down the megadeal and convince you that it’s a good idea. What exactly is AB buying? Understanding why a combined AB InBev SABMiller will be successful requires us to understand what exactly AB is buying. AB is the world’s largest beer producer with a portfolio containing 17 brands with retail sales over $1 billion. Despite the company’s size, they have little to no presence in Africa and Latin America outside of Brazil. These two regions are SABMiller’s top two revenue-generators as shown on the right. Though AB and SAB are the world’s two largest beer companies, they have little SABMiller’s 2015 revenue by region regional overlap. Hence, the combined company will boast a regionally- complimentary brand portfolio. Below is a graphic of the combined company’s global beer production. The yellow represents all the markets that AB can tap into with the acquisition of SAB.