Impact Ejecta Emplacement on Terrestrial Planets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Impact Structures Provide the Only Ground Truth Against Which Computational and Experimental Results Can Be Com Pared

Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1987. 15:245-70 Copyright([;; /987 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved TERRESTRIAL IMI!ACT STRUCTURES ··- Richard A. F. Grieve Geophysics Division, Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario KIA OY3, Canada INTRODUCTION Impact structures are the dominant landform on planets that have retained portions of their earliest crust. The present surface of the Earth, however, has comparatively few recognized impact structures. This is due to its relative youthfulness and the dynamic nature of the terrestrial geosphere, both of which serve to obscure and remove the impact record. Although not generally viewed as an important terrestrial (as opposed to planetary) geologic process, the role of impact in Earth evolution is now receiving mounting consideration. For example, large-scale impact events may hav~~ been responsible for such phenomena as the formation of the Earth's moon and certain mass extinctions in the biologic record. The importance of the terrestrial impact record is greater than the relatively small number of known structures would indicate. Impact is a highly transient, high-energy event. It is inherently difficult to study through experimentation because of the problem of scale. In addition, sophisticated finite-element code calculations of impact cratering are gen erally limited to relatively early-time phenomena as a result of high com putational costs. Terrestrial impact structures provide the only ground truth against which computational and experimental results can be com pared. These structures provide information on aspects of the third dimen sion, the pre- and postimpact distribution of target lithologies, and the nature of the lithologic and mineralogic changes produced by the passage of a shock wave. -

Impact Cratering

6 Impact cratering The dominant surface features of the Moon are approximately circular depressions, which may be designated by the general term craters … Solution of the origin of the lunar craters is fundamental to the unravel- ing of the history of the Moon and may shed much light on the history of the terrestrial planets as well. E. M. Shoemaker (1962) Impact craters are the dominant landform on the surface of the Moon, Mercury, and many satellites of the giant planets in the outer Solar System. The southern hemisphere of Mars is heavily affected by impact cratering. From a planetary perspective, the rarity or absence of impact craters on a planet’s surface is the exceptional state, one that needs further explanation, such as on the Earth, Io, or Europa. The process of impact cratering has touched every aspect of planetary evolution, from planetary accretion out of dust or planetesimals, to the course of biological evolution. The importance of impact cratering has been recognized only recently. E. M. Shoemaker (1928–1997), a geologist, was one of the irst to recognize the importance of this process and a major contributor to its elucidation. A few older geologists still resist the notion that important changes in the Earth’s structure and history are the consequences of extraterres- trial impact events. The decades of lunar and planetary exploration since 1970 have, how- ever, brought a new perspective into view, one in which it is clear that high-velocity impacts have, at one time or another, affected nearly every atom that is part of our planetary system. -

The Recognition of Terrestrial Impact Structures

Bulletin of the Czech Geological Survey, Vol. 77, No. 4, 253–263, 2002 © Czech Geological Survey, ISSN 1210-3527 The recognition of terrestrial impact structures ANN M. THERRIAULT – RICHARD A. F. GRIEVE – MARK PILKINGTON Natural Resources Canada, Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario, KIA 0ES Canada; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Earth is the most endogenically active of the terrestrial planets and, thus, has retained the poorest sample of impacts that have occurred throughout geological time. The current known sample consists of approximately 160 impact structures or crater fields. Approximately 30% of known impact structures are buried and were initially detected as geophysical anomalies and subsequently drilled to provide geologic samples. The recognition of terrestrial impact structures may, or may not, come from the discovery of an anomalous quasi-circular topographic, geologic or geo- physical feature. In the geologically active terrestrial environment, anomalous quasi-circular features, however, do not automatically equate with an impact origin. Specific samples must be acquired and the occurrence of shock metamorphism, or, in the case of small craters, meteoritic fragments, must be demonstrated before an impact origin can be confirmed. Shock metamorphism is defined by a progressive destruction of the original rock and mineral structure with increasing shock pressure. Peak shock pressures and temperatures produced by an impact event may reach several hundreds of gigaPascals and several thousand degrees Kelvin, which are far outside the range of endogenic metamorphism. In addition, the application of shock- wave pressures is both sudden and brief. Shock metamorphic effects result from high strain rates, well above the rates of norma l tectonic processes. -

Appendix a Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable

Appendix A Recovery of Ejecta Material from Confirmed, Probable, or Possible Distal Ejecta Layers A.1 Introduction In this appendix we discuss the methods that we have used to recover and study ejecta found in various types of sediment and rock. The processes used to recover ejecta material vary with the degree of lithification. We thus discuss sample processing for unconsolidated, semiconsolidated, and consolidated material separately. The type of sediment or rock is also important as, for example, carbonate sediment or rock is processed differently from siliciclastic sediment or rock. The methods used to take and process samples will also vary according to the objectives of the study and the background of the investigator. We summarize below the methods that we have found useful in our studies of distal impact ejecta layers for those who are just beginning such studies. One of the authors (BPG) was trained as a marine geologist and the other (BMS) as a hard rock geologist. Our approaches to processing and studying impact ejecta differ accordingly. The methods used to recover ejecta from unconsolidated sediments have been successfully employed by BPG for more than 40 years. A.2 Taking and Handling Samples A.2.1 Introduction The size, number, and type of samples will depend on the objective of the study and nature of the sediment/rock, but there a few guidelines that should be followed regardless of the objective or rock type. All outcrops, especially those near industrialized areas or transportation routes (e.g., highways, train tracks) need to be cleaned off (i.e., the surface layer removed) prior to sampling. -

Remove This Report from Blc8. 25

.:WO _______CUfe\J-&£sSU -ILtXJZ-.__________ T REMOVE THIS REPORT FROM BLC8. 25 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey standards and nomenclature. Prepared by the Geological Survey for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration U )L Interagency Report: 43 GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY OF SUDBURY BASIN, ONTARIO, CANADA (Apollo 17 Training Exercise, 5/23/72-5/25/72) by I/ 2/ Michael R. Dence , Eugene L. Boudette 2/ and Ivo Lucchitta May 1972 Earth Physics Branch Dept. of Energy, Mines & Resources Ottawa, Canada 21 Center of Astrogeology U. S. Geological Survey Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 ERRATA Guide to the geology of Sudbury Basin, Ontario, Canada by Michael R. Dence, Eugene L. Boudette, and Ivo Lucchitta Page ii. Add "(photograph by G. Mac G. Boone) 11 to caption. iii. P. 2, line 5; delete "the" before "data", iv. P. 1, line 3; add "of Canada, Ltd." after "Company", iv. P. 1, line 7; delete "of Canada" after "Company". v. Move entire section "aerial reconnaissance....etc..." 5 spaces to left margin. 1. P. 2, line 6; add "moderate to" after "dips are". 1. P. 2, line 13; change "strike" to "striking". 2. P. 1, line 2; change "there" to "these". 2. P. 2, line 7; change "(1) breccias" to "breccias (1)". 2. P. 3, line 3; add "slate" after "Onwatin". 4. P. 1, line 7; change "which JLs" to "which are". 7. P. 1, line 9; add "(fig. 3)" after "surveys". 7. P. -

ANIC IMPACTS: MS and IRONMENTAL P ONS Abstracts Edited by Rainer Gersonde and Alexander Deutsch

ANIC IMPACTS: MS AND IRONMENTAL P ONS APRIL 15 - APRIL 17, 1999 Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research Bremerhaven, Germany Abstracts Edited by Rainer Gersonde and Alexander Deutsch Ber. Polarforsch. 343 (1999) ISSN 01 76 - 5027 Preface .......3 Acknowledgements .......6 Program ....... 7 Abstracts P. Agrinier, A. Deutsch, U. Schäre and I. Martinez: On the kinetics of reaction of CO, with hot Ca0 during impact events: An experimental study. .11 L. Ainsaar and M. Semidor: Long-term effect of the Kärdl impact crater (Hiiumaa, Estonia) On the middle Ordovician carbonate sedimentation. ......13 N. Artemieva and V.Shuvalov: Shock zones on the ocean floor - Numerical simulations. ......16 H. Bahlburg and P. Claeys: Tsunami deposit or not: The problem of interpreting the siliciclastic K/T sections in northeastern Mexico. ......19 R. Coccioni, D. Basso, H. Brinkhuis, S. Galeotti, S. Gardin, S. Monechi, E. Morettini, M. Renard, S. Spezzaferri, and M. van der Hoeven: Environmental perturbation following a late Eocene impact event: Evidence from the Massignano Section, Italy. ......21 I von Dalwigk and J. Ormö Formation of resurge gullies at impacts at sea: the Lockne crater, Sweden. ......24 J. Ebbing, P. Janle, J, Koulouris and B. Milkereit: Palaeotopography of the Chicxulub impact crater and implications for oceanic craters. .25 V. Feldman and S.Kotelnikov: The methods of shock pressure estimation in impacted rocks. ......28 J.-A. Flores, F. J. Sierro and R. Gersonde: Calcareous plankton stratigraphies from the "Eltanin" asteroid impact area: Strategies for geological and paleoceanographic reconstruction. ......29 M.V.Gerasimov, Y. P. Dikov, 0 . I. Yakovlev and F.Wlotzka: Experimental investigation of the role of water in the impact vaporization chemistry. -

N of L. Superior: Mineralization in Diatremes

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Effect of Volatiles and Target Lithology on the Generation and Emplacement of Impact Crater Fill and Ejecta Deposits on Mars

Effect of volatiles and target lithology on the generation and emplacement of impact crater fill and ejecta deposits on Mars Item Type Proceedings; text Authors Osinski, Gordon R. Citation Osinski, G. R. (2006). Effect of volatiles and target lithology on the generation and emplacement of impact crater fill and ejecta deposits on Mars. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 41(10), 1571-1586. DOI 10.1111/j.1945-5100.2006.tb00436.x Publisher The Meteoritical Society Journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science Rights Copyright © The Meteoritical Society Download date 26/09/2021 23:08:45 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/656199 Meteoritics & Planetary Science 41, Nr 10, 1571–1586 (2006) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Effect of volatiles and target lithology on the generation and emplacement of impact crater fill and ejecta deposits on Mars Gordon R. OSINSKI Canadian Space Agency, 6767 Route de l’Aeroport, Saint-Hubert, Quebec, J3Y 8Y9, Canada E-mail: [email protected] (Received 15 October 2005; revision accepted 15 March 2006) Abstract–Impact cratering is an important geological process on Mars and the nature of Martian impact craters may provide important information as to the volatile content of the Martian crust. Terrestrial impact structures currently provide the only ground-truth data as to the role of volatiles and an atmosphere on the impact-cratering process. Recent advancements, based on studies of several well-preserved terrestrial craters, have been made regarding the role and effect of volatiles on the impact-cratering process. Combined field and laboratory studies reveal that impact melting is much more common in volatile-rich targets than previously thought, so impact-melt rocks, melt-bearing breccias, and glasses should be common on Mars. -

Meteorite Impacts, Earth, and the Solar System

Traces of Catastrophe A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures Bevan M. French Research Collaborator Department of Mineral Sciences, MRC-119 Smithsonian Institution Washington DC 20560 LPI Contribution No. 954 i Copyright © 1998 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion thereof requires the written permission of the Insti- tute as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. Figures 3.1, 3.2, and 3.5 used by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press, Inc. Figures 3.13, 4.16, 4.28, 4.32, and 4.33 used by permission of the publisher, Springer-Verlag. Figure 4.25 used by permission of the publisher, Yale University. Figure 5.1 used by permission of the publisher, Geological Society of America. See individual captions for reference citations. This volume may be cited as French B. M. (1998) Traces of Catastrophe:A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures. LPI Contribution No. 954, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 120 pp. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113, USA Phone:281-486-2172 Fax:281-486-2186 E-mail:[email protected] Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. Cover Art.“One Minute After the End of the Cretaceous.” This artist’s view shows the ancestral Gulf of Mexico near the present Yucatán peninsula as it was 65 m.y. -

PDF Linkchapter

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] A arsenic, 116, 143, 168 brecciation, shock, 225, 231 Ashanti crater, Ghana. See Bosumtwi Brent crater, Ontario, 321 Abitibi Subprovince, 305 crater, Ghana bromine, 137 Acraman depression, South Australia, A thy ris Broodkop Shear Zone, 180 211, 212, 218 gurdoni transversalis, 114 Budevska crater, Venus, 24 geochemistry, 216 hunanensis, 114 Bunyeroo Formation, 209, 210, 219, geochronology, 219 aubrite, 145 220, 221, 222 melt rock, 216, 218 augite, 159 Bushveld layered intrusion, 337 paleomagnetism, 219 Australasian strewn field, 114, 133, See also Acraman impact structure 134, 137, 138, 139, 140, 143, Acraman impact structure, South C 144, 146 Australia, 209 australite, 136, 141, 145, 146 Cabin-Medicine Lodge thrust system, Adelaid Geosyncline, 210, 220, 222 Austria, moldavites, 142 227 adularía, 167 Cabin thrust plate, 173, 225, 226, Aeneas on Dione crater, Earth, 24 227, 231, 232 aerodynamically shaped tektites, 135 B calcite, 112, 166 Al Umchaimin depression, western Barbados, tektites, 134, 139, 142, 144 calcium, 115, 116, 128 Iraq, 259 barium, 116, 169, 216 calcium oxide, 186, 203, 216 albite, 209 Barrymore crater, Venus, 44 Callisto, rings, 30 Algoman granites, 293 Basal Member, Onaping Formation, Cambodia, circular structure, 140, 141 alkali, 156, 159, 167 266, 267, 268, 271, 272, 273, Cambrian, Beaverhead impact alkali feldspar, 121, 123, 127, 211 289, 290, 295, 296, 299, 304, structure, Montana, 163, 225, 232 almandine-spessartite, 200 307, 308, 310, 311, 314 Canadian Arctic, -

The Geological Record of Meteorite Impacts

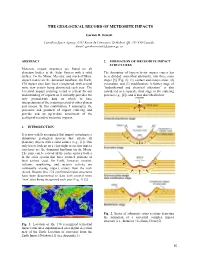

THE GEOLOGICAL RECORD OF METEORITE IMPACTS Gordon R. Osinski Canadian Space Agency, 6767 Route de l'Aeroport, St-Hubert, QC J3Y 8Y9 Canada, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. FORMATION OF METEORITE IMPACT STRUCTURES Meteorite impact structures are found on all planetary bodies in the Solar System with a solid The formation of hypervelocity impact craters has surface. On the Moon, Mercury, and much of Mars, been divided, somewhat arbitrarily, into three main impact craters are the dominant landform. On Earth, stages [3] (Fig. 2): (1) contact and compression, (2) 174 impact sites have been recognized, with several excavation, and (3) modification. A further stage of more new craters being discovered each year. The “hydrothermal and chemical alteration” is also terrestrial impact cratering record is critical for our considered as a separate, final stage in the cratering understanding of impacts as it currently provides the process (e.g., [4]), and is also described below. only ground-truth data on which to base interpretations of the cratering record of other planets and moons. In this contribution, I summarize the processes and products of impact cratering and provide and an up-to-date assessment of the geological record of meteorite impacts. 1. INTRODUCTION It is now widely recognized that impact cratering is a ubiquitous geological process that affects all planetary objects with a solid surface (e.g., [1]). One only has to look up on a clear night to see that impact structures are the dominant landform on the Moon. The same can be said of all the rocky and icy bodies in the solar system that have retained portions of their earliest crust. -

The Effect of Target Lithology on the Products of Impact Melting

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 43, Nr 12, 1939–1954 (2008) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org The effect of target lithology on the products of impact melting G. R. OSINSKI 1*, R. A. F. GRIEVE2, G. S. COLLINS3, C. MARION4, and P. SYLVESTER4 1Departments of Earth Sciences/Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario, 1151 Richmond Street, London, ON N6A 5B7, Canada 2Earth Sciences Sector, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa, ON K1A 0E4, Canada 3IARC, Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom 4Department of Earth Sciences, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL A1B 3X5, Canada *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 31 March 2008; revision accepted 04 September 2008) Abstract–Impact cratering is an important geological process on the terrestrial planets and rocky and icy moons of the outer solar system. Impact events generate pressures and temperatures that can melt a substantial volume of the target; however, there remains considerable discussion as to the effect of target lithology on the generation of impact melts. Early studies showed that for impacts into crystalline targets, coherent impact melt rocks or “sheets” are formed with these rocks often displaying classic igneous structures (e.g., columnar jointing) and textures. For impact structures containing some amount of sedimentary rocks in the target sequence, a wide range of impact- generated lithologies have been described, although it has generally been suggested that impact melt is either lacking or is volumetrically minor. This is surprising given theoretical constraints, which show that as much melt should be produced during impacts into sedimentary targets.