Chapter 5: Lagos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mis-Education of the African Child: the Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925

Athens Journal of History - Volume 7, Issue 2, April 2021 – Pages 141-162 The Mis-education of the African Child: The Evolution of British Colonial Education Policy in Southern Nigeria, 1900–1925 By Bekeh Utietiang Ukelina Education did not occupy a primal place in the European colonial project in Africa. The ideology of "civilizing mission", which provided the moral and legal basis for colonial expansion, did little to provide African children with the kind of education that their counterparts in Europe received. Throughout Africa, south of the Sahara, colonial governments made little or no investments in the education of African children. In an attempt to run empire on a shoestring budget, the colonial state in Nigeria provided paltry sums of grants to the missionary groups that operated in the colony and protectorate. This paper explores the evolution of the colonial education system in the Southern provinces of Nigeria, beginning from the year of Britain’s official colonization of Nigeria to 1925 when Britain released an official policy on education in tropical Africa. This paper argues that the colonial state used the school system as a means to exert power over the people. Power was exercised through an education system that limited the political, technological, and economic advancement of the colonial people. The state adopted a curricular that emphasized character formation and vocational training and neglected teaching the students, critical thinking and advanced sciences. The purpose of education was to make loyal and submissive subjects of the state who would serve as a cog in the wheels of the exploitative colonial machine. -

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

The Politics of Architecture and Ur-Banism In

The Politics of Architecture and Urbanism in Postcolonial Lagos, 1960–1986 DANIEL IMMERWAHR Department of History, University of California, Berkeley This is a preprint of an article to appear in the Journal of African Cultur- al Studies 19:2 (December 2007). It will be available online at http://journalsonline.tandf.co.uk/ After independence, the Nigerian government faced a number of choices about how to manage its urban environment, particularly in Lagos, Ni- geria’s capital. By favoring a program of tropical modernist architecture for its prestige buildings in Lagos and British New Town style for its housing estates there, the government sought to demonstrate both its in- dependence from European culture and its ability to perform the func- tions of a modern state. And yet, the hopes of government officials and elites for Lagos were frustrated as Lagosians, in response to new eco- nomic and demographic forces, shaped a very different sort of city from below. The Nigerian government’s retreat to Abuja and its abandonment of Lagos mark the failures of urban policymaking in Nigeria. 1. Colonial and Postcolonial Cities In the past twenty-five years, historians have devoted a good deal of attention to the spatial aspects of colonial rule. The ―colonial city‖ has emerged as an archetype fundamentally different from the metropolitan city. Anthony King‘s pioneering work (1976, 1990) emphasized the im- portance of the world economy in determining the shape of colonial ci- ties, and a number of case studies, including those of Janet Abu-Lughod (1980), Gwendolyn Wright (1991), Anja Nevanlinna (1996), and Zeynep Çelik (1997) have further explored the consequences of colonial urban policy. -

Heial Gazette

gx?heial© Gazette No. 87 LAGOS -*4th November, 1965 CONTENTS Page : Page Movements of Officers 1802-11 Loss of Assessment of Duty Book -¢ 1833 Applications for Registration of Trade Unions - 1811 Loss of Hackney Carriage Driver’s Badges... 1833 Probate Notices 1811-12 Loss of Revenue Collectors Receipt .. 1834 Notice of Proposal to declare a Pioneer \ Recovery of Lost Government Marine Industry 1812 Warrants . - 1834 Granting of a Pioneer Certificate — 1813 Loss of Specific Import Licences i. « 1834 i Application to eonstruct a Leat 1813 Loss of Local Purchase Orders 1834 Application for an Oil Pipeline Licence 1813-4 Admission into Queen’s College, 1966 1835 Appointments of Notary Public 1814-5 Admission into King’s College, 1966 - 1836 Addition to the List of Notaries Public 1815 Tenders 1837-8 Corrigenda 1815 Vacancies 1838-45 Nigeria Trade Journal Vol. 13 No. 3.. 1815 Competition of Entry into the Administrative and Special Departmental Classes of the Release of Two Values of the New Definitive Eastern Nigeria Public Service, 1966 1845-6 Postage Stamps . .. ws 1816 _ Adult Education Evening Classes, 1966 . - 1847-8 Transfer of Control—OporomaPostal Agency 1816 : : Federal School of Science, Lagos—Evening : Prize Draw—National Premium Bonds 1816-7 Classes, 1966 + . 1848 Board of Customs and Excise—Customs and Board of Customs and Excise—Sale of " 1849-52 Excise Notice No. 44 -- 1818-20 Goods oe .. .e Re Lats Treasury Returns Nos, 2, 3, 3.1, 3.2, and 4 1821-5 Official Gazette—Renewal Notice 1. 1853" Federal Land Registry—Registration of Titles .- - os 1826-33 INDEX TO Lecat Notice in SUPPLEMENT Appointmentof Member of National Labour L.N. -

Jalabi Practice: a Critical Appraisal of a Socio-Religious Phenomenon in Yorubaland, Nigeria

ISSN 2411-9563 (Print) European Journal of Social Sciences September-December 2015 ISSN 2312-8429 (Online) Education and Research Volume 2, Issue 4 Jalabi Practice: a Critical Appraisal of a Socio-Religious Phenomenon in Yorubaland, Nigeria Dr. Afiz Oladimeji Musa [email protected] International Islamic University Malaysia Prof. Dr. Hassan Ahmad Ibrahim [email protected] International Islamic University Malaysia Abstract Jalabi is an extant historical phenomenon with strong socio-religious impacts in Yorubaland, south-western part of Nigeria. It is among the preparatory Dawah strategies devised by the Yoruba Ulama following the general mainstream Africa to condition the minds of the indigenous people for the acceptance of Islam. This strategy is reflected in certain socio-religious services rendered to the clients, which include, but not limited to, spiritual consultation and healing, such as petitionary Dua (prayer), divination through sand-cutting, rosary selection, charm-making, and an act of officiating at various religious functions. In view of its historicity, the framework of this research paper revolves around three stages identified to have been aligned with the evolution of Jalabi, viz. Dawah, which marked its initial stage, livelihood into which it had evolved over the course of time, and which, in turn, had predisposed it to the third stage, namely syncretism. Triangulation method will be adopted for qualitative data collection, such as interviews, personal observation, and classified manuscript collections, and will be interpretively and critically analyzed to enhance the veracity of the research findings. The orality of the Yoruba culture has greatly influenced the researcher’s decision to seek data beyond the written words in order to give this long-standing phenomenon its due of study and to help understand the many dimensions it has assumed over time, as well as its both positive and adverse effects on the socio-religious live of the Yoruba people of Nigeria. -

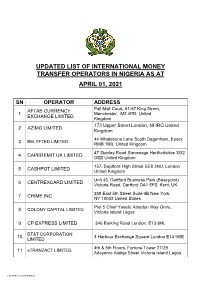

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

Analysis of Management Practices in Lagos State Tertiary Institutions Through Total Quality Management Structural Framework

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.7, No.8, 2016 Analysis of Management Practices in Lagos State Tertiary Institutions through Total Quality Management Structural Framework Abbas Tunde AbdulAzeez Faculty of Education, Lagos State University Ojo Campus, Ojo, Lagos State, Nigeria Abstract This research investigated total quality management practices and quality teacher education in public tertiary institutions in Lagos State. The study was therefore designed to analyse management practices in Lagos state tertiary institutions through total quality management structural framework. The selected public tertiary institutions in Lagos State were Lagos State University (LASU) Ojo, University of Lagos (UNILAG) Akoka, Michael Otedola College of Primary Education (MOCOPED) Inaforija, Epe, Federal College of Education Technical (FCET)Akoka, and Adeniran Ogunsanya College of Education (AOCOED) Oto-Ijanikin. A descriptive survey research design was adopted. A Total Quality Management practices and Quality Teacher Education Questionnaire (TQMP-QTEQ) was used to obtain data for the study. The structured questionnaire was administered on 905 academic and non-academic staff members and final year students of sampled institutions using purposive sampling technique. The questionnaire was content-validated using expert opinion method and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistics of sampling adequacy. In terms of the measure of reliability, the Cronbach’s Alpha values for the two major constructs of the study are satisfactory – quality teacher education (0.838) and TQM (0.879). Their Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistics of sampling adequacy were equally above the acceptable standard of 0.7. The hypotheses were tested at the 5 percent level of significance. -

Here Is a List of Assets Forfeited by Cecilia Ibru

HERE IS A LIST OF ASSETS FORFEITED BY CECILIA IBRU 1. Good Shepherd House, IPM Avenue , Opp Secretariat, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers) 2. Residential block with 19 apartments on 34, Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Dilivent International Limited). 3.20 Oyinkan Abayomi Street, Victoria Island (remainder of lease or tenancy upto 2017). 4. 57 Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi. 5. 5A George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited), 6. 5B George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 7. 4A Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 8. 4B Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 9. 16 Glover Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 10. 35 Cooper Road , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 11. Property situated at 3 Okotie-Eboh, SW Ikoyi. 12. 35B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi. 13. 38A Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Meeky Enterprises Limited). 14. 38B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Aleksander Stankov). 15. Multiple storey multiple user block of flats under construction 1st Avenue , Banana Island , Ikoyi, Lagos , (with beneficial interest therein purchased from the developer Ibalex). 16. 226, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 17. 182, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos , (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 18. 12-storey Tower on one hectare of land at Ozumba Mbadiwe Water Front, Victoria Island . -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

Curriculum Vitae Fagbayi, Tawakalt Ajoke

CURRICULUM VITAE FAGBAYI, TAWAKALT AJOKE PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS 1, Omidiji street, Otto, Ebute-Metta, Lagos Nigeria TEL NO: 08094105289/0701151913 E-MAILS: [email protected] [email protected] FAGBAYI, T.A. Page 1 PERSONAL DATA FULL NAME: FAGBAYI, Tawakalt Ajoke PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH: Ebute-Metta, Lagos, Nigeria 8th December, 1983 PERMANENT Home ADDRESS 1, Omidiji street, Otto, Ebute-Metta, Lagos, Nigeria. SEX: Female NATIONALITY Nigerian STATE/ LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA Lagos State/ Mainland LGA MARITAL STATUS: Single NUMBER OF CHILDREN: None POSTAL ADDRESS Departement of Cell Biology & Genetics, Fauclty of Science, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria TEL NO: 08094105289/0701151913 E-MAILS: [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: (with dates) POST SECONDARY Qualifications Dates University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos Ph.D. Cell & Molecular Biology in-view • University of Lagos, Akoka Lagos. MSc. Cell Biology & Genetics 2009-2010 • University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos BSc. Cell Biology & Genetics 2003-2007 Second Class, Upper Division SECONDARY • Grace High School, Gbagada, Lagos, WASC 1996-2001 FAGBAYI, T.A. Page 2 ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS University Degree Class (If any) Institution Date of Award B.Sc. Hons Cell Biology & Second Class upper University of Lagos, 2008 Genetics Division Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria. M. Sc. Cell Biology and ,, 2010 Genetics Ph.D. Cell & Molecular ,, In - view Biology STATEMENT OF EXPERIENCE: PAST WORK & TEACHING EXPERIENCE Employer Designation Date Nature of Duty Department of Cell Facilitator and December 2014 Actively involved in all aspects of workshop Biology and Genetics Organizer March 2015 planning, including workshop simulation, University of Lagos, CBG Molecular compilation and acquisition of workshop Workshop & DNA materials, as well as facilitation of some Basics Workshop topics and hands-on practicals during workshop. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

Standard Chartered Bank Branch Network from 1St

STANDARD CHARTERED BANK BRANCH ST NETWORK FROM 1 JANUARY 2019 REGION BRANCH ADDRESS Ahmadu Bello No. 142, Ahmadu Bello Way, Victoria Island, Lagos (Head Office) Tel: +234 (1) 2368146, +234 (1) 2368154 Airport Road No. 53, Murtala Mohammed International Airport Road, Lagos Tel:234 (1) 2368686 Ajose Adeogun Plot 275, Ajose Adeogun, Victoria Island, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368051, +234 (1) 2368185 Apapa No. 40, Warehouse Road, Apapa, Lagos Tel:+234 (1) 2368752, +234 (1) 2367396 Aromire No. 30, Aromire Street, Ikeja, Lagos Tel:+234 (1) 2368830 – 1 Awolowo Road No.184, Awolowo Road, Ikoyi, Lagos LAGOS Tel:+234 (1) 2368852, +234 (1) 2368849 Broad Street No. 138/146, Broad Street, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368790, +234 (1) 2368611 Ikeja GRA No. 47, Isaac John Street, GRA Ikeja, Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2368836 Ikota Shops K23 - 26, 41 & 42 Ikota Shopping Complex, 1/F Beside VGC, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Lagos. Tel:+234 (1) 2368841, 234 (1) 2367262 Ilupeju No. 56, Town Planning way, Ilupeju, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368845, +234 (1) 2367186 Lekki Phase 1 Plot 24b Block 94, Lekki Peninsula Scheme 1, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368432, +234 (1) 2367294 New Leisure Mall Leisure Mall, 97/99 Adeniran Ogunsanya Street, Surulere, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368827, +234 (1) 2367212 Maryland Shopping Mall 350 – 360, Ikorodu Road, Anthony, Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2267009 Novare Mall Novare Lekki Mall, Monastery Road, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Sangotedo, Lekki-Ajah Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2367518 Sanusi Fafunwa Plot 1681 Sanusi Fafunwa Street, Victoria Island, Lagos Tel: +234 (1)