Arxiv:1912.00685V2 [Gr-Qc] 30 Mar 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotating Stars in Relativity

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Rotating Stars in Relativity Vasileios Paschalidis Nikolaos Stergioulas · Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Rotating relativistic stars have been studied extensively in recent years, both theoretically and observationally, because of the information they might yield about the equation of state of matter at extremely high densi- ties and because they are considered to be promising sources of gravitational waves. The latest theoretical understanding of rotating stars in relativity is re- viewed in this updated article. The sections on equilibrium properties and on nonaxisymmetric oscillations and instabilities in f-modes and r-modes have been updated. Several new sections have been added on equilibria in modi- fied theories of gravity, approximate universal relationships, the one-arm spiral instability, on analytic solutions for the exterior spacetime, rotating stars in LMXBs, rotating strange stars, and on rotating stars in numerical relativ- ity including both hydrodynamic and magnetohydrodynamic studies of these objects. Keywords Relativistic stars · Rotation · Stability · Oscillations · Magnetic fields · Numerical relativity Vasileios Paschalidis Theoretical Astrophysics Program, Departments of Astronomy and Physics, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Department of Physics, Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544, USA E-mail: [email protected] http://physics.princeton.edu/~vp16/ Nikolaos Stergioulas Department of Physics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece E-mail: [email protected] http://www.astro.auth.gr/~niksterg arXiv:1612.03050v2 [astro-ph.HE] 30 Nov 2017 2 Vasileios Paschalidis, Nikolaos Stergioulas The article has been substantially revised and updated. New Section 5 and various Subsections (2.3 { 2.5, 2.7.5 { 2.7.7, 2.8, 2.10-2.11,4.5.7) have been added. -

Relativistic Stars with a Linear Equation of State: Analogy with Classical Isothermal Spheres and Black Holes

A&A 483, 673–698 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20078287 & c ESO 2008 Astrophysics Relativistic stars with a linear equation of state: analogy with classical isothermal spheres and black holes P. H. Chavanis Laboratoire de Physique Théorique (UMR 5152 du CNRS), Université Paul Sabatier, 118 route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse, France e-mail: [email protected] Received 16 July 2007 / Accepted 10 February 2008 ABSTRACT We complete our previous investigations concerning the structure and the stability of “isothermal” spheres in general relativity. This concerns objects that are described by a linear equation of state, P = q, so that the pressure is proportional to the energy density. In the Newtonian limit q → 0, this returns the classical isothermal equation of state. We specifically consider a self-gravitating radiation (q = 1/3), the core of neutron stars (q = 1/3), and a gas of baryons interacting through a vector meson field (q = 1). Inspired by recent works, we study how the thermodynamical parameters (entropy, temperature, baryon number, mass-energy, etc.) scale with the size of the object and find unusual behaviours due to the non-extensivity of the system. We compare these scaling laws with the area scaling of the black hole entropy. We also determine the domain of validity of these scaling laws by calculating the critical radius (for a given central density) above which relativistic stars described by a linear equation of state become dynamically unstable. For photon stars (self-gravitating radiation), we show that the criteria of dynamical and thermodynamical stability coincide. Considering finite spheres, we find that the mass and entropy present damped oscillations as a function of the central density. -

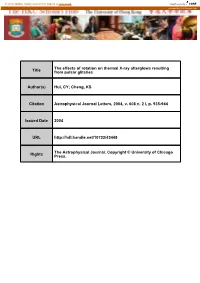

Title the Effects of Rotation on Thermal X-Ray Afterglows Resulting from Pulsar Glitches Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub The effects of rotation on thermal X-ray afterglows resulting Title from pulsar glitches Author(s) Hui, CY; Cheng, KS Citation Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2004, v. 608 n. 2 I, p. 935-944 Issued Date 2004 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/43448 The Astrophysical Journal. Copyright © University of Chicago Rights Press. The Astrophysical Journal, 608:935–944, 2004 June 20 # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE EFFECTS OF ROTATION ON THERMAL X-RAY AFTERGLOWS RESULTING FROM PULSAR GLITCHES C. Y. Hui and K. S. Cheng Department of Physics, University of Hong Kong, Chong Yuet Ming Physics Building, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China; [email protected], [email protected] Received 2003 December 3; accepted 2004 March 1 ABSTRACT We derive the anisotropic heat transport equation for rotating neutron stars, and we also derive the thermal equilibrium condition in a relativistic rotating axisymmetric star through a simple variational argument. With a simple model of a neutron star, we model the propagation of heat pulses resulting from transient energy releases inside the star. Such sudden energy release can occur in pulsars during glitches. Even in a slow rotation limit ( 1 ; 103 sÀ1), the results with rotational effects involved could be noticeably different from those obtained with a spherically symmetric metric in terms of the timescales and magnitudes of thermal afterglow. We also study the effects of gravitational lensing and frame dragging on the X-ray light curve pulsations. -

Rotating Stars in Relativity

Living Rev Relativ (2017) 20:7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41114-017-0008-x REVIEW ARTICLE Rotating stars in relativity Vasileios Paschalidis1,2 · Nikolaos Stergioulas3 Received: 8 December 2016 / Accepted: 3 October 2017 / Published online: 29 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Rotating relativistic stars have been studied extensively in recent years, both theoretically and observationally, because of the information they might yield about the equation of state of matter at extremely high densities and because they are considered to be promising sources of gravitational waves. The latest theoretical understanding of rotating stars in relativity is reviewed in this updated article. The sec- tions on equilibrium properties and on nonaxisymmetric oscillations and instabilities in f -modes and r-modes have been updated. Several new sections have been added on equilibria in modified theories of gravity, approximate universal relationships, the one-arm spiral instability, on analytic solutions for the exterior spacetime, rotating stars in LMXBs, rotating strange stars, and on rotating stars in numerical relativity including both hydrodynamic and magnetohydrodynamic studies of these objects. Keywords Relativistic stars · Rotation · Stability · Oscillations · Magnetic fields · Numerical relativity This article is a revised version of https://doi.org/10.12942/lrr-2003-3. Change summary: Major revision, updated and expanded. Change details: The article has been substantially revised and updated. Expanded all sections, and moved former Subsect. 2.10 to Sect. 3. The number of references (now 863) has more than doubled. B Nikolaos Stergioulas [email protected] Vasileios Paschalidis [email protected] 1 Theoretical Astrophysics Program, Departments of Astronomy and Physics, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 2 Department of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 3 Department of Physics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 123 7 Page 2 of 169 V. -

Neutron Star Collapse Times, Gamma-Ray Bursts and Fast Radio Bursts

MNRAS 441, 2433–2439 (2014) doi:10.1093/mnras/stu720 The birth of black holes: neutron star collapse times, gamma-ray bursts and fast radio bursts ‹ Vikram Ravi1,2 and Paul D. Lasky1 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/441/3/2433/1126394 by California Institute of Technology user on 24 June 2019 1School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia 2CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, Australia Telescope National Facility, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia Accepted 2014 April 8. Received 2014 April 7; in original form 2013 November 29 ABSTRACT Recent observations of short gamma-ray bursts (SGRBs) suggest that binary neutron star (NS) mergers can create highly magnetized, millisecond NSs. Sharp cut-offs in X-ray afterglow plateaus of some SGRBs hint at the gravitational collapse of these remnant NSs to black holes. The collapse of such ‘supramassive’ NSs also describes the blitzar model, a leading candidate for the progenitors of fast radio bursts (FRBs). The observation of an FRB associated with an SGRB would provide compelling evidence for the blitzar model and the binary NS merger scenario of SGRBs, and lead to interesting constraints on the NS equation of state. We predict the collapse times of supramassive NSs created in binary NS mergers, finding that such stars collapse ∼10–4.4 × 104 s (95 per cent confidence) after the merger. This directly impacts observations targeting NS remnants of binary NS mergers, providing the optimal window for high time resolution radio and X-ray follow-up of SGRBs and gravitational wave bursts. -

Gravitation and Multimessenger Astrophysics Imre Bartos

Gravitation and Multimessenger Astrophysics by Imre Bartos Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 c 2012 Imre Bartos All Rights Reserved Abstract Gravitation and Multimessenger Astrophysics by Imre Bartos Gravitational waves originate from the most violent cosmic events, which are often hidden from traditional means of observation. Starting with the first direct observation of gravita- tional waves in the coming years, astronomy will become richer with a new messenger that can help unravel many of the yet unanswered questions on various cosmic phenomena. The ongoing construction of advanced gravitational wave observatories requires disruptive innovations in many aspects of detector technology in order to achieve the sensitivity that lets us reach cosmic events. We present the development of a component of this technology, the Advanced LIGO Optical Timing Distribution System. This technology aids the detection of relativistic phenomena through ensuring that time, at least for the observatories, is absolute. Gravitational waves will be used to look into the depth of cosmic events and understand the engines behind the observed phenomena. As an example, we examine some of the plausible engines behind the creation of gamma ray bursts. We anticipate that, by reaching through shrouding blastwaves, efficiently discovering off-axis events, and observing the central engine at work, gravitational wave detectors will soon transform the study of gamma ray bursts. We discuss how the detection of gravitational waves could revolutionize our understanding of the progenitors of gamma ray bursts, as well as related phenomena such as the properties of neutron stars. -

Pos(MPCS2015)012 , M

Numerical models of isolated rotating compact stars PoS(MPCS2015)012 J. Novak∗, M. Oertel, D. Chatterjee and A. Sourie LUTH, Observatoire de Paris, PSL Research University, CNRS, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon E-mail: [email protected] Realistic global neutron star models require numerical approach. Here, we briefly motivate and recall the general-relativistic framework for the description of rotating compact stars and show how global observable quantities can be computed unambiguously. Then, we present some recent results on the building of more detailed physical models, including realistic microphysics, fol- lowing two directions. First, we describe the inclusion of magnetic field and its effects on both, global equilibrium and equation of state, and finally we discuss superfluid (two-fluid) models in an attempt to model glitch phenomena. The Modern Physics of Compact Stars 2015 30 September 2015 - 3 October 2015 Yerevan, Armenia ∗Speaker. c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). http://pos.sissa.it/ Compact star numerical models J. Novak 1. Introduction The building of compact stars models requires inputs from many different fields of physics, with overall conditions that can hardly be tested on Earth. These include nuclear physics, with cold, highly asymmetric nuclear matter; general relativity, with stars possessing a very strong grav- itational field (only a black hole can possess a stronger one); electromagnetism, with an intense magnetic field up to about 1013 T; and special relativity, with rotation velocities approaching that of light for rapidly rotating stars. -

Compact Relativistic Star with Quadratic Envelope

Pramana – J. Phys. (2019) 92:40 © Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12043-018-1695-x Compact relativistic star with quadratic envelope P MAFA TAKISA1,2, S D MAHARAJ1 ,∗ and C MULANGU2 1Astrophysics and Cosmology Research Unit, School of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa 2Department of Electrical Engineering, Mangosuthu University of Technology, Umlazi, Durban 4031, South Africa ∗Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] MS received 9 June 2018; accepted 17 July 2018; published online 1 February 2019 Abstract. We consider an uncharged anisotropic stellar model with two distinct equations of state in general relativity. The core layer has a quark matter distribution with a linear equation of state. The envelope layer has a matter distribution which is quadratic. The interfaces between the core, envelope and the vacuum exterior regions are smoothly matched. We find radii, masses and compactifications for five different compact objects which are consistent with other investigations. In particular, the properties of the pulsar object PSR J1614-2230 are studied. The metric functions and the matter distribution are regular throughout the star. In particular, it is shown that the radii associated with the core and the envelope can change for different parameter values. Keywords. General relativity; relativistic star; equation of state. PACS Nos 04.20.–q; 04.20.Jb; 04.40.Dg 1. Introduction Hartle [6] pointed out that when the matter density of a spherical stellar compact object is much higher The study of the physical behaviour in superdense than the nuclear density, it is difficult to have an exact astronomical objects is an important subject for inves- description of stellar matter distributions. -

Relativistic Fluid Dynamics

Living Reviews in Relativity (2021) 24:3 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41114-021-00031-6 REVIEW ARTICLE Relativistic fluid dynamics: physics for many different scales Nils Andersson1 · Gregory L. Comer2 Received: 1 June 2020 / Accepted: 22 January 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract The relativistic fluid is a highly successful model used to describe the dynam- ics of many-particle systems moving at high velocities and/or in strong gravity. It takes as input physics from microscopic scales and yields as output predictions of bulk, macroscopic motion. By inverting the process—e.g., drawing on astrophysi- cal observations—an understanding of relativistic features can lead to insight into physics on the microscopic scale. Relativistic fluids have been used to model sys- tems as “small” as colliding heavy ions in laboratory experiments, and as large as the Universe itself, with “intermediate” sized objects like neutron stars being considered along the way. The purpose of this review is to discuss the mathematical and theo- retical physics underpinnings of the relativistic (multi-) fluid model. We focus on the variational principle approach championed by Brandon Carter and collaborators, in which a crucial element is to distinguish the momenta that are conjugate to the particle number density currents. This approach differs from the “standard” text-book deriva- tion of the equations of motion from the divergence of the stress-energy tensor in that one explicitly obtains the relativistic Euler equation as an “integrability” condition on the relativistic vorticity. We discuss the conservation laws and the equations of motion in detail, and provide a number of (in our opinion) interesting and relevant applications This article is a revised version of https://doi.org/10.12942/lrr-2007-1. -

Innermost Stable Circular Orbits and Epicyclic Frequencies Around a Magnetized Neutron Star

129129 Univ.Univ. Sci. Sci. 201 2013,4, V Vol. 1 (): 3 doi:doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC1 10.11144/Jav -. FreelyFreely available available on on line line ORIGINALORIGINAL ARTICLEPAPER Innermost stable circular orbits and epicyclic frequencies around a magnetized neutron star Andrés F. Gutiérrez-Ruiz1, Leonardo A. Pachón1, César A. Valenzuela-Toledo2 B Abstract A full-relativistic approach is used to compute the radius of the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO), the Keplerian, frame-dragging, precession and oscillation frequencies of the radial and vertical motions of neutral test particles orbiting the equatorial plane of a magnetized neutron star. The space-time around the star is modelled by the six parametric solution derived by Pachón et al. (2012) It is shown that the inclusion of an intense magnetic field, such as the one of a neutron star, have non-negligible effects on the above physical quantities, and therefore, its inclusion is necessary in order to obtain a more accurate and realistic description of physical processes, such as the dynamics of accretion disks, occurring in the neighbourhood of this kind of objects. The results discussed here also suggest that the consideration of strong magnetic fields may introduce non-negligible corrections in, e.g., the relativistic precession model and therefore on the predictions made on the mass of neutron stars. Keywords: Relativistic precession frequencies; innermost stable circular orbits; neutron stars. Edited by Humberto Rafeiro & Alberto Acosta Introduction 1 Grupo de Física Atómica y Molecular, Instituto de Física, Fac- ultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Antioquia Stellar models are generally based on the Newto-nian UdeA; Calle 70 No. -

A New Class of Analytical Solutions Describing Anisotropic Neutron Stars in General Relativity

A New Class of Analytical Solutions Describing Anisotropic Neutron Stars in General Relativity Jay Solanki Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology, Surat - 395007, Gujarat, India E-mail: [email protected] Bhashin Thakore Department of Physics, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich - 80539, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new class of solutions describing analytical solutions for compact stellar structures has been developed within the tenets of General Relativity. Con- sidering the inherent anisotropy in compact stars, a stable and causal model for realistic anisotropic neutron stars was obtained using the general theory of relativity. Assuming a physically acceptable non-singular form of one metric potential and radial pressure containing the curvature parameter ', the constant :, and the radius A, analytical solutions to Einstein’s field equa- arXiv:2108.00161v1 [gr-qc] 31 Jul 2021 tions for anisotropic matter distribution were obtained. Taking the value of : as -0.44, it was found that the proposed model obeys all necessary physical conditions, and it is potentially stable and realistic. The model also exhibits a linear equation of state, which can be applied to describe compact stars. Keywords: Anisotropic compact star; general relativity; EOS; interior solu- tion. 1 1 Introduction A star towards the end of its life has exhausted all of its fuel, and undergoes core collapse[1, 2]. When the collapsing core is approximately between 1.4 to 3 " , it becomes a neutron star. To decipher the nature of such exotic compact bod- ies is made possible through careful perusal of Einstein’s field equations and the Schwarzschild metric. Ruderman[3] and Canuto [4] proposed that highly compact stars are anisotrop- ically composed. -

Homologous Stellar Models and Polytropes Main Sequence Stars

Homologous Stellar Models and Polytropes Main Sequence Stars Post-Main Sequence Hydrogen-Shell Burning Post-Main Sequence Helium-Core Burning White Dwarfs, Massive and Neutron Stars Degenerate Gas Equation of State and Chandrasekhar Mass White Dwarf Cooling Massive Star Evolution Core Collapse and Supernova Explosion Energetics Introduction In this lecture, consideration is given to final evolution stages and this too is dependent on mass. The vast majority of stars become white dwarfs in which all nuclear • reactions have ceased. Interest therefore centres on cooling, structural changes during cooling and the cooling time. Equally important is what the study of white dwarfs can reveal about their progenitors on the Asymptotic Giant Branch. Very massive stars (& 8 M ) experience mass-loss throughout their • evolution and for this reason their evolution is substantially different from that of lower mass stars. Very massive stars (& 8 M ) are neutron star and black hole progen- • itors following a supernova explosion. Circumstances leading to a neutron star, as opposed to a black hole, • need to be understood. Equation of State of a Degenerate Gas { I So far it has been assumed that stars are formed of ideal gases although degeneracy pressure has been mentioned in connection with cores formed at the centres of lower mass stars on the RGB and AGB. Degeneracy pressure resists gravitational collapse and in connection with white dwarfs, the final evolution stage for most stars, this idea now needs to be developed. At high densities, gas particles become so close that interactions between them can no • longer be ignored. Beyond the regime where pressure ionisation becomes important, as pressure on a highly • ionised gas is further increased the Pauli Exclusion Principle becomes relevant.