Exploring Core and Peripheral Insurgencies in India's Northeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

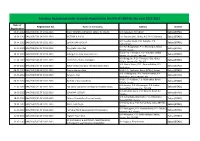

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Current Status of Insurgencies in Northeast India

THE INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN Registered under societies registration Act No. XXI of 1860 The Institute of Strategic Studies was founded in 1973. It is a non- profit, autonomous research and analysis centre, designed for promoting an informed public understanding of strategic and related issues, affecting international and regional security. In addition to publishing a quarterly Journal and a monograph series, the ISS organises talks, workshops, seminars and conferences on strategic and allied disciplines and issues. BOARD OF GOVERNORS Chairman Ambassador Khalid Mahmood MEMBERS Dr. Tariq Banuri Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ali Chairman, Higher Education Vice Chancellor Commission, Islamabad Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad Ex-Officio Ex-Officio Foreign Secretary Finance Secretary Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ministry of Finance Islamabad Islamabad Ambassador Seema Illahi Baloch Ambassador Mohammad Sadiq Ambassador Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry Director General Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad (Member and Secretary Board of Governors) Current Status of Insurgencies in Northeast India Muhammad Waqas Sajjad * & Muhammad Adeel Ul Rehman** September 2019 * Muhammad Waqas Sajjad was Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad. ** Muhammad Adeel Ul Rehman was an intern at ISSI from September- November 2017. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief : Ambassador Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry Director General, ISSI Editor : Najam Rafique Director Research Publication Officer : Azhar Amir Malik Composed and designed by : Syed Muhammad Farhan Title Cover designed by : Sajawal Khan Afridi Published by the Director General on behalf of the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad. Publication permitted vide Memo No. 1481-77/1181 dated 7-7-1977. ISSN. 1029-0990 Articles and monographs published by the Institute of Strategic Studies can be reproduced or quoted by acknowledging the source. -

China's New Game in India's Northeast

MANTRAYA ANALYSIS#15: 04 JULY 2017 China’s New Game in India’s Northeast - Bibhu Prasad Routray - Abstract Could China be drastically altering its policy with regard to insurgency movements in India’s northeastern region? A series of developments point at that direction. To blunt India’s assertive postures under the BJP-led government, Beijing could be gradually unveiling a grand design to revive the battered insurgencies. Provision of safe houses, supply of weapons, and even playing a more prominent role in directing attacks on security forces could be emerging as Beijing’s instrumentalities to disturb peace in the fragile northeast and checkmate India’s Act East policy. India’s relations with Myanmar that can defeat this Chinese ploy, therefore, assumes greater importance. New Delhi must take notice. (Map of India’s Northeastern States) Every revolutionary has a right to utilise China’s space and armoury in a true spirit of internationalism. – Chairman Mao Zedong In the 1960s and 1970s, insurgents from Nagaland travelled to China for training and also to seek support for their armed struggle.[1]While some of the outfits received training in East Pakistan, till the late 1970s and early 1980s China reportedly provided arms and finances to these outfits. Beijing’s support, however, ended coinciding with the power struggle within the Communist Party. While a minor flow of arms and ammunition did continue from the arms manufacturing units in mainland China to the war chests of various insurgent formations operating in the Northeast, Beijing’s decision to stay clear of the insurgencies in the region continued. -

Vicenç Fisas Vicenç Fisas Armengol (Barcelona, 1952) Is the Director of the School for a Culture of Peace at the Autonomous University of Barcelona

Peace diplomacies Negotiating in armed conflicts Vicenç Fisas Vicenç Fisas Armengol (Barcelona, 1952) is the director of the School for a Culture of Peace at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford (UK) and won the National Human Rights Award in 1988. He is the author of more than 40 books on peace, conflicts, disarmament and peace processes. He has published the “Yearbook of Peace Processes” since 2006, and in the past two decades he has participated in some of these peace processes. (http://escolapau.uab.cat). School for a Culture of Peace PEACE DIPLOMACIES: NEGOTIATING IN ARMED CONFLICTS Vicenç Fisas Icaria Más Madera Peace diplomacies: Negotiating in armed conflicts To my mother and father, who gave me life, something too beautiful if it can be enjoyed in conditions of dignity, for anyone, no matter where they are, and on behalf of any idea, to think they have the right to deprive anyone of it. CONTENTS Introduction 11 I - Armed conflicts in the world today 15 II - When warriors visualise peace 29 III - Design and architecture of peace processes: Lessons learned since the crisis 39 Common options for the initial design of negotiations 39 Crisis situations in recent years 49 Proposals to redesign the methodology and actors after the crisis 80 The actors’ “tool kit”: 87 Final recommendations 96 IV – Roles in a peace process 99 V - Alternative diplomacies 111 VI – Appendixes 129 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years. 130 Peace agreements and ratification of -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

Unit-26 History and Geographical Spread

UNIT-26 HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD . Structure 26.0 Objectives 26.1 Introduction 26.2 Cultural Pattern . 26.3 Geographical Spread:Tribal Zones 263.1, Northern and North-Eastern 2633' Central _ 2633 . South-Western 263.4 . Scattered 26.4 History, Language and Ethnicity 26.4.1 Northern and North-eakern Tribes 26.42 Central Indian Tribes 26.43 South-Western Tribes 26.4.4 Scattered Tribes 265 Let Us Sum Up 26.6 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A DaMa Tribal Girl, Gqjarat. Appendix ( 26.0 OBJECTIVES ; i, This Unit attempts to analyse history and geographical spread of tribes. After reading this unit you uould know about : / cultural spread of tribes, and , the tribal culture with respect to its history and geographical spread in the Northern, NorthiEastem, Central, South-Westem, and scattered zones, and 1 languhges and ethnicity of a few tribes. { 26.1 INTRODUCTION -+ The tribal groups are presumed to form the oldest ethnological sector of the national population. Tribal population of India is spread all over the country. However, in Haryana, Punjab,Chandigarh, DeUli,Goa and Pondicherry there exist very little tribal population.The rest of the states and union territories possess fairly good number of tribal population. You wiU find that forest and hilly areas possess greater concentration of tribal population; while in the plains their number isquite less. Madhya Pradesh registers the largest number oftribes (73) followed by Anrnachal Pradesh (62), Orissa (56), Maharashtra (52), Andhra Pradesh (43), etc. The vast variety and numbers of Indian tribes and tribal groups have\always been a matter of great social and literary discourse for the past several decades. -

Rengma Nagas Demand Autonomous Council

Rengma Nagas demand autonomous council They write to Union Home Minister and Assam Chief Minister, asking for their voices to be heard Vijaita Singh have no history in the Reng- the Rengma Nagas, whose New Delhi ma Hills. People who are population is around The Rengma Nagas in Assam presently living in Rengma 22,000. We are also de- have written to Union Home Hills are from Assam, Aruna- manding a separate legisla- Minister Amit Shah demand- chal Pradesh and Meghalaya. tive seat for Rengmas,” he ing an autonomous district They speak different dialects said. council amid a decision by and do not know Karbi lan- The National Socialist the Central and the State go- guage of Karbi Anglong,” the Council of Nagaland or NSCN vernments to upgrade the memorandum said. (Isak-Muivah), which is in Karbi Anglong Autonomous RNPC president K. Solo- talks with the Centre for a Council (KAAC) into a terri- mon Rengma told The Hindu peace deal, said in a state- torial council. that the government was on ment on Monday that the The Rengma Naga Peo- the verge of taking a decision Rengma issue was one of the ples’ Council (RNPC), a regis- Long fight:The Rengma Naga community has been seeking without taking them on important agendas of the tered body, said in the mem- board and thus they had “Indo-Naga political talks” an automous council for many years now. * FILE PHOTO orandum that the Rengmas written to Mr. Shah and and no authority should go were the first tribal people in Narrating its history, the sam and Nagaland at the Chief Minister Himanta Bis- far enough to override their Assam to have encountered council said that during the time of creation of Nagaland wa Sarma. -

Role of Economic Development and Governance in Mitigating Ethnic Insurgency: a Case Study of Tripura, India

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com Role of Economic Development and Governance in Mitigating Ethnic Insurgency: A Case Study of Tripura, India Sanjib Banik1, Gurudas Das2 1) Michael Madhusudan Dutta College, Sabroom, Tripura, India 2) National Institute of Techonology Silchar, Assam, India Date of publication: March 30th, 2019 Edition period: March 2019– July2019 To cite this article: Banik, S., & Das, G. (2019). Role of Economic Development and Governance in Mitigating Ethnic Insurgency: A Case Study of Tripura, India. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences,8(1), 51-78. doi:10.17583/rimcis.2019.4053 To link this article: http://doi.org/10.17583/rimcis.2019.4053 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License(CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 8 No.1 March 2019pp. 51-78 Role of Economic Development and Governance in Mitigating Insurgency: A Case Study of Tripura, India Sanjib Banik Gurudas Das Michael Madhusudan Dutta National Institute of Technology College Silchar Abstract The purpose of this paper is two folds: firstly, to analyze the short run and long run relationship between insurgency on the one hand and economic development and governance on the other and secondly, to determine the direction of causality between these three variables in Tripura, one of the conflict-ridden states in India during 1980- 2005. With the application of auto-regressive distributed lag model (ARDL), an inverse relationship has been established which formalises the descriptive notions about the cointegration between insurgency on the one hand and economic development and governance on the other in the long run. -

ADMINISTRATION and POLITICS in TRIPURA Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY

ADMINISTRATION AND POLITICS IN TRIPURA MA [Political Science] Third Semester POLS 905 E EDCN 803C [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Biswaranjan Mohanty Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, SGTB Khalsa College, University of Delhi Authors: Neeru Sood, Units (1.4.3, 1.5, 1.10, 2.3-2.5, 2.9, 3.3-3.5, 3.9, 4.2, 4.4-4.5, 4.9) © Reserved, 2017 Pradeep Kumar Deepak, Units (1.2-1.4.2, 4.3) © Pradeep Kumar Deepak, 2017 Ruma Bhattacharya, Units (1.6, 2.2, 3.2) © Ruma Bhattacharya, 2017 Vikas Publishing House, Units (1.0-1.1, 1.7-1.9, 1.11, 2.0-2.1, 2.6-2.8, 2.10, 3.0-3.1, 3.6-3.8, 3.10, 4.0-4.1, 4.6-4.8, 4.10) © Reserved, 2017 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. -

Home-Makers Without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam

Home-Makers without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam Wasbir Hussain Home-Makers without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed here are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Preface………….....……….........………......................…….. 5 Acknowledgements………….....………………......................…….. 7 Conflict Dynamics in Assam: An Introduction ................................. 9 Home-Makers without the Men ....................................................... 14 Survivors of terror: Pariahs in society? ...................................... 19 How Lakshi Hembrom lost her power to think ......................... 23 Life’s cruel jokes on Kamrun Nissa ........................................... 27 Family ties cost Bharati Dear .................................................... -

The Other Burma (Webspread PDF, 742KB)

TheConflict, counter-insurgency other Burma? and human rights in Northeast India Ben Hayes Contents 1. Introduction: where east meets west 4 2. Conflict and insec urity in Northeast India 6 3. Counter-insurg ency and human rights 10 4. Problems facing women and children 12 5. The rule of law 14 6. Resource extraction, hydro-electric power and land acquisition 15 7. Freedom of association and expression 21 8. Conclusions 24 Acknowledgements 9. Recommendations 25 The author is very grateful to Rick van der Woud for his considerable input into this report and to Max Rowlands for editing the text. Further reading 26 Notes 27 The other Burma? Conflict, counter-insurgency and human rights in Northeast India The other Burma? Conflict, counter-insurgency and human rights in Northeast India Northeast India (NEI) is a triangle-shaped territory sandwiched between Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar/ Burma (hereafter: Burma) and Bangladesh and connected to the rest of the country via a thin strip of land known as the ‘Chicken’s Neck’. It comprises the State of Sikkim and parts of West Bengal (the neck) plus the seven ‘sister states’ of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. estled in the foothills of the Himalayas, and because of the Today the people of NEI face many challenges. Fifty years of N mountain range, NEI is the physical gateway between India, conflict has led to a strong military presence and engendered a China and Southeast Asia. Strategically important to both coun- culture of violence. Prolonged underdevelopment and the forces tries, China also claims the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh of modernisation and globalisation have opened the region to as part of South Tibet.