Journal of Military and Veterans' Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oseberg Ship

V 46 B78o A 1 1 6 8 5 4 1 1^6 OSEBERG SHIP by ANTON WILHELM BROGGER Professor of Archeeology in the University of Christiania Price Fifty Cents Reprinted from The American-Scandinavian Revi. July 1921 The Oseberg Ship By Anton Wilhelm Broggek 4^ The ships of the Viking Age discovered in Norway count among the few national productions of antiquity that have attained world wide celebrity. And justly so, for they not only give remarkable evidence of a unique heathen burial custom, but they also bear witness to a very high culture which cannot fail to be of interest to the world outside. The Oseberg discoveries, the most remarkable and abundant anti- quarian find in Norway, contain a profusion of art, a wealth of objects and phenomena, coming from a people who just at that time, ,"^ of Europe. ^ the ninth century, began to come into contact with one-half ^ It was a great period and it has given us great monuments. We have long been acquainted with its literature. Such a superb production as Egil Skallagrimson's Sonartorrek, which is one hundred years later than the Oseberg material, is a worthy companion to it. / The Oseberg ship was dug out of the earth and caused the great- est astonishment even among Norwegians. Who could know that on that spot, an out of the way barrow on the farm of Oseberg in the parish of Slagen, a little to the north of Tcinsberg, there would be excavated the finest and most abundant antiquarian discoveries of Norway? Xtj^^s in the summer of the year 1903 that a farmer at Oseberg began to dig the })arrow. -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Air Force Trades Contents Introduction to the Take Your Trade Further in the Air Force

AIR FORCE TRADES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE TAKE YOUR TRADE FURTHER IN THE AIR FORCE .................................4 QUALIFIED TRADES ...........................................................................12 AIR FORCE TRADES AIRCRAFT SPRAY PAINTER ...............................................................13 ELECTRICIAN ....................................................................................14 It may come as a surprise to you but the Air Force has a lot to offer tradies in a vast variety of jobs. Becoming FITTER & TURNER .............................................................................15 part of one of Australia’s most dynamic organisations will give you the opportunity to work on some of the TRAINEESHIPS ..................................................................................16 most advanced aircraft and sophisticated equipment available. You’ll be in an environment where you will be AIRCRAFT ARMAMENT TECHNICIAN .................................................17 challenged and have an opportunity to gain new skills, or even further the skills you already have. AERONAUTICAL LIFE SUPPORT FITTER .............................................18 AIRCRAFT TECHNICIAN .....................................................................19 AVIONICS TECHNICIAN ......................................................................20 CARPENTER ......................................................................................21 COMMUNICATION ELECTRONIC TECHNICIAN ....................................22 -

Dame Lucy Neville-Rolfe DBE, CMG, FCIS Biography ______

Dame Lucy Neville-Rolfe DBE, CMG, FCIS Biography ___________________________________________________________________________ Non-Executive President of Eurocommerce since July 2012, Lucy Neville-Rolfe began her retail career in 1997 when she joined Tesco as Group Director of Corporate Affairs. She went on to also become Company Secretary (2004-2006) before being appointed to the Tesco plc Board where she was Executive Director (Corporate and Legal Affairs) from 2006 to January 2013. Lucy is a life peer and became a member of the UK House of Lords on 29 October 2013. Before Tesco she worked in a number of UK Government departments, starting with the then Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, where she was private secretary to the Minister. She was a member of the UK Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1992 – 1994 where her responsibilities included home and legal affairs. She later became Director of the Deregulation Unit, first in the DTI and then the Cabinet Office from 1995 - 1997. In 2013 Lady Neville-Rolfe was elected to the Supervisory Board of METRO AG. She is also a member of the UK India Business Advisory Council. She is a Non-Executive Director of ITV plc, and of 2 Sisters Food Group, a member of the PWC Advisory Board and a Governor of the London Business School. She is a former Vice– President of Eurocommerce and former Deputy Chairman of the British Retail Consortium In 2012 she was made a DBE (Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in the Queen’s Birthday Honours in recognition of her services to industry and the voluntary sector. -

Contents Theresa May - the Prime Minister

Contents Theresa May - The Prime Minister .......................................................................................................... 5 Nancy Astor - The first female Member of Parliament to take her seat ................................................ 6 Anne Jenkin - Co-founder Women 2 Win ............................................................................................... 7 Margaret Thatcher – Britain’s first woman Prime Minister .................................................................... 8 Penny Mordaunt – First woman Minister of State for the Armed Forces at the Ministry of Defence ... 9 Lucy Baldwin - Midwifery and safer birth campaigner ......................................................................... 10 Hazel Byford – Conservative Women’s Organisation Chairman 1990 - 1993....................................... 11 Emmeline Pankhurst – Leader of the British Suffragette Movement .................................................. 12 Andrea Leadsom – Leader of House of Commons ................................................................................ 13 Florence Horsbrugh - First woman to move the Address in reply to the King's Speech ...................... 14 Helen Whately – Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party ............................................................. 15 Gillian Shephard – Chairman of the Association of Conservative Peers ............................................... 16 Dorothy Brant – Suffragette who brought women into Conservative Associations ........................... -

Of the Viking Age the Ornate Burials of Two Women Within the Oseberg Ship Reveals the Prominent Status That Women Could Achieve in the Viking Age

T The Oseberg ship on display in The Viking Ship Museum. Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo Queen(s) of the Viking Age The ornate burials of two women within the Oseberg ship reveals the prominent status that women could achieve in the Viking Age. Katrina Burge University of Melbourne Imagine a Viking ship burial and you probably think homesteads and burials that tell the stories of the real of a fearsome warrior killed in battle and sent on his women of the Viking Age. The Oseberg burial, which journey to Valhöll. However, the grandest ship burial richly documents the lives of two unnamed but storied ever discovered—the Oseberg burial near Oslo—is not a women, lets us glimpse the real world of these women, monument to a man but rather to two women who were not the imaginings of medieval chroniclers or modern buried with more wealth and honour than any known film-makers. warrior burial. Since the burial was uncovered more than a century ago, historians and archaeologists have The Ship Burial tried to answer key questions: who were these women, Dotted around Scandinavia are hundreds of earth mounds, how did they achieve such prominence, and what do they mostly unexcavated and mainly presumed to be burials. tell us about women’s lives in this time? This article will The Oseberg mound was excavated in 1904, revealing that explore current understandings of the lives and deaths the site’s unusual blue clay had perfectly preserved wood, of the Oseberg women, and the privileged position they textiles, metal and bone. -

Raaf Base. Wagga

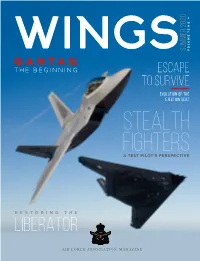

SUMMER 2020 WINGS NO.4 72 VOLUME QANTAS: THE BEGINNING ESCAPE TO SURVIVE EVOLUTION OF THE EJECTION SEAT STEALTH FIGHTERS A TEST PILOT'S PERSPECTIVE RESTORING THE LIBERATOR AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE defencebank.com.au 1800 033 139 The credit card that has tails wagging. Introducing Australia’s Defence Bank Foundation VISA Credit card. It’s a win for members, a win for veterans and a win for specially-trained dogs like Bruce, whose handsome face appears on the card. .99 p.a.% .99 p.a.% 6 month Ongoing 3 introductory rate.* 8 rate.* • Up to 55 days interest free on purchases. • Same low rate for purchases and cash advances. • Additional cardholder at no extra cost. Australia’s Defence Bank Foundation supports the Defence Community Dogs’ Program. It provides specially-trained assistance dogs to veterans living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Thanks to you, we’ll donate half of the annual card fee every year to do what we can to serve those who protect us. Find out why this credit card is getting tongues and tails wagging at defencebank.com.au/creditcard *Rates are current as 1 October 2020 and subject to change. Introductory rate is applicable for the first six months and then reverts to the variable credit card rate, currently 8.99% p.a. Credit eligibility criteria, terms and conditions, fees and charges apply. Card is issued by Defence Bank Limited ABN 57 087 651 385 AFSL / Australian Credit Licence 234582. CONTENTS. ON THE COVER Two stealthy birds from the Skunk Works stable: Jim Brown flying the F-117 and the late Dave Cooley flying the F-22. -

House of Lords Library Note: the Life Peerages Act 1958

The Life Peerages Act 1958 This year sees the 50th anniversary of the passing of the Life Peerages Act 1958 on 30 April. The Act for the first time enabled life peerages, with a seat and vote in the House of Lords, to be granted for other than judicial purposes, and to both men and women. This Library Note describes the historical background to the Act and looks at its passage through both Houses of Parliament. It also considers the discussions in relation to the inclusion of women life peers in the House of Lords. Glenn Dymond 21st April 2008 LLN 2008/011 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Life peerages – an historical overview .......................................................................... 2 2.1 Hereditary nature of peerage................................................................................... 2 2.2 Women not summoned to Parliament ..................................................................... 2 2.3 Early life peerages.................................................................................................. -

Warriors Walk Heritage Trail Wellington City Council

crematoriumchapel RANCE COLUMBARIUM WALL ROSEHAUGH AVENUE SE AFORTH TERRACE Wellington City Council Introduction Karori Cemetery Servicemen’s Section Karori Serviceman’s Cemetery was established in 1916 by the Wellington City Council, the fi rst and largest such cemetery to be established in New Zealand. Other local councils followed suit, setting aside specifi c areas so that each of the dead would be commemorated individually, the memorial would be permanent and uniform, and there would be no distinction made on the basis of military or civil rank, race or creed. Unlike other countries, interment is not restricted to those who died on active service but is open to all war veterans. First contingent leaving Karori for the South African War in 1899. (ATL F-0915-1/4-MNZ) 1 wellington’s warriors walk heritage trail Wellington City Council The Impact of Wars on New Zealand New Zealanders Killed in Action The fi rst major external confl ict in which New Zealand was South African War 1899–1902 230 involved was the South African War, when New Zealand forces World War I 1914–1918 18,166 fought alongside British troops in South Africa between 1899 and 1902. World War II 1939–1945 11,625 In the fi rst decades of the 20th century, the majority of New Zealanders Died in Operational New Zealand’s population of about one million was of British descent. They identifi ed themselves as Britons and spoke of Services Britain as the ‘Motherland’ or ‘Home’. Korean War 1950–1953 43 New Zealand sent an expeditionary force to the aid of the Malaya/Malaysia 1948–1966 20 ‘Mother Country’ at the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914. -

The History Journal Volume 14

annual service of rededication Order of St John St Hohn Historyenduring faith Awkward Hours, Awkward Jobs Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia Christ Church Anglican Cathedral Frank Dunstan MStJ Darwin Historical Society of Australia annual service of rededication Order of St John St Hohn Historyenduring faith THE JOURNAL OF THE ST JOHN AMBULANCE HISTORICALCapitular SOCIETY Procession OF AUSTRALIA of the Priory in Australia Christ ChurchVOLUME Anglican 14, 2014 Cathedral ‘Preserving and promoting the St John heritage’ Historical Society of Australia Darwin Frank Dunstan MStJ Awkward Hours, Awkward Jobs The front cover of St John History Volume 14 shows the members of the Order of St John who took part in the Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia at their annual service of rededication in Christ Church Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia Anglican Cathedral in Darwin on Sunday 2 June 2013. enduring faith The members of the Order are pictured outside the porch of the cathedral, which is all that remains of the original structure built and consecrated in 1902. Constructed from the local red limestone, the original Christ Church Anglican Cathedral cathedral was damaged during a Japanese air raid in February 1942. After that the Australian military forces annual service of rededication used the building until the end of the war. Cyclone Tracy destroyed everything but the porch of the repaired cathedral in December 1974. Order of St John The new cathedral, built around and behind the porch, was consecrated in the presence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Reverend Donald Coggan, on 13 March 1977. -

Print This Article

242 Salvage Stories, Preserving Narratives, and Museum Ships Andrew Sawyer* Abstract Preserved ships and other vessels are associated with a historiography, in Europe at least, which is still marked by parochialism, antiquarianism, and celebratory narrative. Many evidence difficult histories, and they are also extremely expensive to preserve. Yet, they are clearly valued, as nations in Europe invest heavily in them. This survey examines a range of European examples as sites of cultural, political and national identity. An analytical framework foregrounding the role of narrative and story reveals three aspects to these exhibits: explicit stories connected with specific nations, often reinforcing broader, sometimes implicit, national narratives; and a teleological sequence of loss, recovery and preservation, influenced by nationality, but very similar in form across Europe. Key words: European; maritime; ships; narrative; nationalism; identity; museums. Introduction European nations value their maritime and fluvial heritage, especially as manifested in ships and boats. What may be the world’s oldest watercraft, from around 8,000 BC, is preserved at the Drents Museum in Assen, the Netherlands (Verhart 2008: 165), whilst Greece has a replica of a classical Athenian trireme, and Oslo has ships similar to those used by the Norse to reach America. Yet, such vessels are implicated in a problematic historiography (Smith 2011) tending to parochialism and antiquarianism (Harlaftis 2010: 214; Leffler 2008: 57-8; Hicks 2001), and which often (for whatever reason) avoids new historiographical approaches in favour of conventional celebratory narratives (Witcomb 2003: 74). They are also linked to well-known problematic histories of imperialism and colonialism. They are sites of gender bias: ‘Vasa has from its construction to its excavation been the prerogative and the playground of men’ (Maarleveld 2007: 426), and they are still popularly seen as providing access to ‘toys for boys’ (Gardiner 2009: 70). -

Song of the Beauforts

Song of the Beauforts Song of the Beauforts No 100 SQUADRON RAAF AND BEAUFORT BOMBER OPERATIONS SECOND EDITION Colin M. King Air Power Development Centre © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Approval has been received from the owners where appropriate for their material to be reproduced in this work. Copyright for all photographs and illustrations is held by the individuals or organisations as identified in the List of Illustrations. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release, distribution unlimited. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. First published 2004 Second edition 2008 Published by the Air Power Development Centre National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: King, Colin M. Title: Song of the Beauforts : No 100 Squadron RAAF and the Beaufort bomber operations / author, Colin M. King. Edition: 2nd ed. Publisher: Tuggeranong, A.C.T. : Air Power Development Centre, 2007. ISBN: 9781920800246 (pbk.) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Beaufort (Bomber)--History. Bombers--Australia--History World War, 1939-1945--Aerial operations, Australian--History.