Vulnerability of Children Living in the Red Light Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tollygunge Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-152-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-827-8 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 167 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Ward-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Ward by Population Size | 11-12 Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) | Religious -

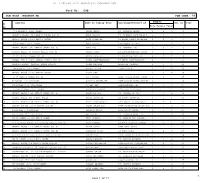

Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 7/2 KHANPUR SHAID NAGAR ABALA GAYAN LT. GOBINDA GAYAN 2 2 4 2 2 GANGULY BAGAN 23A GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ABHA BAGCHI LT. BHABANI PADA BAGCHI 4 3 7 3 3 NETAJI NAGAR 11/23 NETAJI NAGAR ALOK MUKERJEE LT BIMAL KANTI MUKERJEE 2 2 4 6 4 55 KHANPUR SOHID NAGAR AMAL BISWAS LATE GOPAL BISWAS 3 1 4 7 5 NETAJI NAGAR 2/42 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMAL DAS LT. MANMATO DAS 3 0 3 8 6 SUBHAS PALLY 33 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 AMITA DUTTA LT LAKSHMINARAYAN DUTTA 0 1 1 9 7 7/11B NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMIYA BALA SIL LT.NARENDRA NATH SIL 0 3 3 10 8 SUBHAS PALLY 32A/1 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 ANIMA BHATTHACHARYA LT MUKUL BHATTACHARYA 0 1 1 11 9 GANGULY BAGAN GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ANIMA DEVNATH PRAFULLY DEVNATH 1 4 5 12 10 9A KHANPUR SOHIDNAGAR ANJALI SINHA JIBAN SINHA 1 2 3 13 11 NETAJI NAGAR 8/76C NETAJI NAGAR ANJAN DEY 2 2 4 14 12 1/37 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ANJU DUTTA LATE SUSHIL KUMAR DUTTA 1 2 3 15 13 BIJOYGAR 5/17 BIJOYGAR ANURUPA MUKHERJEE LATE KOLLAN KUMAR MUKHERJ 0 1 1 16 14 POLLYSREE 15/1 POLLYSREE APURBA DEY HARAPRASANNA DEY 2 1 3 17 15 1/2/5 KHANPUR SAHID NAGAR ARABINDA BISWAS LATE SUSHIL BISWAS 1 1 2 18 16 NETAJI NAGAR 1/40 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ARABINDA DAS LT. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2010 Rescued, Rehabilitated, Returned: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal Robynne A. Locke University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Locke, Robynne A., "Rescued, Rehabilitated, Returned: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Sex Trafficking in India and Nepal" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 378. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/378 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. RESCUED, REHABILITATED, RETURNED: INSTITUTIONAL APPROACHES TO THE REHABILITATION OF SURVIVORS OF SEX TRAFFICKING IN INDIA AND NEPAL __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Robynne A. Locke June 2010 Advisor: Richard Clemmer-Smith, Phd ©Copyright by Robynne A. Locke 2010 All Rights Reserved Author: Robynne A. Locke Title: Institutional Approaches to the Rehabilitation of Survivors of Trafficking in India and Nepal Advisor: Richard Clemmer-Smith Degree Date: June 2010 Abstract Despite participating in rehabilitation programs, many survivors of sex trafficking in India and Nepal are re-trafficked, ‘voluntarily’ re-enter the sex industry, or become traffickers or brothel managers themselves. -

Sexual Slavery Without Borders: Trafficking for Commercial Sexual

International Journal for Equity in Health BioMed Central Research Open Access Sexual slavery without borders: trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India Christine Joffres*1, Edward Mills1, Michel Joffres1, Tinku Khanna2, Harleen Walia3 and Darrin Grund1 Address: 1Simon Fraser University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Blusson Hall, Room 11300, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6, Canada, 2State Coordinator, Bihar Anti-trafficking Resource, Centre Apne Aap Women Worldwide http://www.apneaap.org, Jagdish Mills Compound, Forbesganj, Araria, Bihar 841235, India and 3Technical Support – Child Protection, GOI (MWCD)/UNICEF, 253/A Wing – Shastri Bhavan,, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Marg,, New Delhi:110001, India Email: Christine Joffres* - [email protected]; Edward Mills - [email protected]; Michel Joffres - [email protected]; Tinku Khanna - [email protected]; Harleen Walia - [email protected]; Darrin Grund - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 25 September 2008 Received: 17 March 2008 Accepted: 25 September 2008 International Journal for Equity in Health 2008, 7:22 doi:10.1186/1475-9276-7-22 This article is available from: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/7/1/22 © 2008 Joffres et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Trafficking in women and children is a gross violation of human rights. However, this does not prevent an estimated 800 000 women and children to be trafficked each year across international borders. Eighty per cent of trafficked persons end in forced sex work. -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

'10 9Fi~

Of~ DH FWS/HOW /2267 /17 ~: 08.09.2017 ~ ~ ~"15\!)t ~ ~ ~ ~ \Q~ ~q/o~/~o~~ ~ 9fi£r ~ HFWINRHM-20/2006/Part-III1631 \£l~ 15T~1"'l1~1 I5lt~l~ ~'8~ ~ ~ '8 @1f<1~~1 ~~t~l~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ \£l~ I5Tl~ll"15~ ~~ @c:ttCAfJ~ \£l~ ~~ ~~ <1>1<1Pi"15l~~ W~ ~ C~ @'8> ~ ~ ~~~~~~I "h'l<1~ g ~) ~<1(;'j~I~ R<1I~\!) / ~ / I5Tll1l(;'j\!)"15'1"15~FQ.~(ft1 ~ ~ ~~(;'jl~ 15T1C<1I1"'l~ ~I ~) 15l'f~ W~ I5l<1A~ ~~~ ~ ~ <11~"'11~ ~I ~~I"'l~*9f ~ ~ \!)1M"15I I5lt>1IC~ w~ \5Bf EPIC '8 ~1"'l"1511$ \Q~ ~\!)J@\!) ~ ~ ~ ~ ~I~ <11>1-aJ"'l'>1M<1'¢"'lfl W~ ~ \!)I~ '>1M<1IC~~c<n9f ~ ~ ~ ~I e) Jfl~ W~ <IWf ~/~/~o~q ~ ~o C~ 80 ~ ~~ ~ ~I \!)~ ~/~~ ~~(;'jICI1~ ~ ~~ - 80 ~ ~I 8) W~ I5l<1A~ ~ <n >1~~(;'jj ~ 15l<1~;f ~ ~I ~~ <n >1~~(;'jj ~ W~ ~ ~ ~ ~I @tlj\!)~ ~~ c<n9fJ\5i mr W~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~<ijJI~"'l <n RC<1[j"'lI~~ ~ onl c) ~ '8~ \£l~~ ~ ~ ~H~~C'}~ JfVfJUi, ~ W~ ~ \Q~~ ~~<p '8m<Pm9fr1~~~ ~~ "1~Jfl9fi£r~ ~ 15T$'~ f<k<1[j"'lI~c<n9fJ~I ~) >11<1C>14Jr~~ 'ri111"'l"15I~~1~>1~C~~(~~ BWu) ~oo~ ~ ~~ \!)~ ~9fiOf ~ \!)~ ~/~~ "1~Jfl9fi£r~ ~ ~~~,*C"'l~ ~ RC<1f5\!)~ (~~ C<f~~)1 q) 15T1C<1I1"'l"15JlVlfI~~ C<f~ ~~ ~\!)Jlrn\!) ~ ~ ~ ~ :- <p) \St;U\!)IMC~ "1~Jfl9fi£r<n ~~ <n >1~~(;'jJ ~ \!iU\SMG *1 ~) \Q~ <11~"'11~ ~ ~ 9fi£r (EPIC)/~l"'l"1511$1 9f) ~~ ~~ V1"8m ~~ ~9fi£r (\!)~ ~, ~~ '8 15l"'ll1"'ll GT;r~ ~~, ~~ ~ C<f~ ~)I '4) ~~ ~~ V1"8m ~ ~ '8 ~ ~HI$~ C9fI~~'8>>1I1>jJ/ ~ W~ ~ / ~~<p '8m<Pm ~I (~ ~)I @) W~ ~1,*~>1~ ~ <1Sf9r 9ftJfC9f11~; ~B Wil ~9ft£f ~~ ~~ C<f~ \£l~ 15T1C<1I1"'l~ JlVlf ~'8> "iff ~ 15T1C<1I1"'l9fi£r ~ ~ ~I ~~ '10 9fi~ I5l<1A~ <p) C~ @) ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~I '0-) ~~ ~ ~~ W~ >11,*IC\!)~~ >11,*IC\!)~~, -

Child Trafficking in India

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Human Trafficking 2013 Trafficking at the University of Nebraska 10-2013 Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz Helwan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5 Abdelaziz, Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah, "Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India" (2013). Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking at the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz This article reviews the current research on domestic trafficking of children in India. Child trafficking in India is a highly visible reality. Children are being sold for sexual and labor exploitation, adoption, and organ harvesting. The article also analyzes the laws and interventions that provide protection and assistance to trafficked children. There is no comprehensive legislation that covers all forms of exploitation. Interven- tions programs tend to focus exclusively on sex trafficking and to give higher priority to rehabilitation than to prevention. Innovative projects are at a nascent stage. Keywords: human trafficking, child trafficking, child prostitution, child labor, child abuse Human trafficking is based on the objectification of a human life and the treat- ment of that life as a commodity to be traded in the economic market. -

Compendium of Best Practices on Anti Human Trafficking

Government of India COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS Acknowledgments ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ms. Ashita Mittal, Deputy Representative, UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia The Working Group of Project IND/ S16: Dr. Geeta Sekhon, Project Coordinator Ms. Swasti Rana, Project Associate Mr. Varghese John, Admin/ Finance Assistant UNODC is grateful to the team of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi for compiling this document: Ms. Bharti Ali, Co-Director Ms. Geeta Menon, Consultant UNODC acknowledges the support of: Dr. P M Nair, IPS Mr. K Koshy, Director General, Bureau of Police Research and Development Ms. Manjula Krishnan, Economic Advisor, Ministry of Women and Child Development Mr. NS Kalsi, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Ms. Sumita Mukherjee, Director, Ministry of Home Affairs All contributors whose names are mentioned in the list appended IX COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS © UNODC, 2008 Year of Publication: 2008 A publication of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110 021 www.unodc.org/india Disclaimer This Compendium has been compiled by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights for Project IND/S16 of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the Government of India or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The designations used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, frontiers or boundaries. -

Report, the Term ‘Child’ Is Taken to Mean All Children Below the Age of 18 Years

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS X AFFIRMATION X GLOSSARY/ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS X WORKING DEFINITIONS X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY X PART I. INTRODUCTION X Ƈ Human trafficking – a global phenomenon Ƈ Legal framework and definition Ƈ Child trafficking for sexual purposes in india Ƈ West bengal Ƈ Background to the project Ƈ Purpose and objectives of the present baseline PART II. METHODOLOGY X Ƈ Data collection tools Ƈ Quantitative component Ƈ Qualitative component Ƈ Research team Ƈ Most vulnerable children Ƈ Ethics Ƈ Limitations 2 World Vision India 2018 | 3 PART III. DEMOGRAPHICS OF STUDY POPULATION X Ƈ Children and their caregivers (Darjeeling and 24 south parganas) Ƈ Single mothers in commercial Sexual exploitation (cse) living in sonagachi PART IV. COMMERCIAL SEXUAL EXPLOITATION X & TRAFFICKING IN WEST BENGAL Ƈ Current estimates of human trafficking in west bengal Ƈ International debate about Sex trafficking and sex work Ƈ Life trajectories of women in cse in sonagachi Ƈ Work and migration history Ƈ Vulnerability factors and reasons for getting into cse Ƈ Processes for entry into cse Ƈ Living and working conditions Ƈ Hopes for the future PART V. PARENTING AND CAREGIVERS X RELATIONSHIP TO THEIR CHILDREN Ƈ Caring practices of parents (Darjeeling/24 south parganas) Ƈ Connection to caregivers Ƈ Knowledge about the local Ƈ Caring environment occurrence of trafficking Ƈ Violent discipline Ƈ Causes of trafficking Ƈ Perceptions of safety Ƈ Stigma and trafficking Ƈ Caring for children in sonagachi Ƈ Basic needs PART VIII. CHILD PROTECTION SERVICES X Ƈ Early childhood development Ƈ Knowledge about protective Ƈ Child discipline actions from trafficking Ƈ Knowledge about services PART VI. -

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC 2015-16

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC 2015-16 BIDHANNAGAR COLLEGE GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL EB-02, SECTOR-I SALT LAKE KOLKATA-700064 WEST BENGAL Revised Guidelines of IQAC and submission of AQAR Page 1 CONTENTS Part – A 1. Details of the Institution 3 2. IQAC Composition and Activities 6 Part – B 3. Criterion – I: Curricular Aspects 9 4. Criterion – II: Teaching, Learning and Evaluation 10 5. Criterion – III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 13 6. Criterion – IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 17 7. Criterion – V: Student Support and Progression 19 8. Criterion – VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 22 9. Criterion – VII: Innovations and Best Practices 26 10. Abbreviation 31 10.Annexure – 1 32 11. Annexure – 2 33 12. Annexure – 3 35 13. Annexure – 4 38 14. Annexure – 5 67 Revised Guidelines of IQAC and submission of AQAR Page 2 The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Part – A AQAR for the year 2015 - 16 1. Details of the Institution 1.1 Name of the Institution BIDHANNAGAR COLLEGE 1.2 Address Line 1 EB - 2 Address Line 2 SECTOR I City/Town: SALT LAKE State: WEST BENGAL Pin Code: 700064 [email protected] Institution e-mail address: Contact Nos.: 033-23374761 Name of the Head of the Institution: DR. MADHUMITA MANNA Tel. No. with STD Code: 033-23374782 Mobile: 9903072249 Revised Guidelines of IQAC and submission of AQAR Page 3 Name of the IQAC Co-ordinator: SRI ARUP KUMAR HAIT Mobile: 9433878779 IQAC e-mail address: [email protected] WBCOGN12751 1.3 NAAC Track ID(For ex. -

A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003

NHRC - UNIFEM - ISS Project A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003 Coordinator Sankar Sen Principal Investigator - Researcher P.M. Nair IPS Volume I Institute of Social Sciences National Human Rights Commission UNIFEM New Delhi New Delhi New Delhi Final Report of Action Research on Trafficking in Women and Children VOLUME – 1 Sl. No. Title Page Reference i. Contents i ii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Justice Dr. A.S. Anand, Chairperson, NHRC) iii-iv iii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Sujata V. Manohar) v-vi iv. Foreword (by Ms. Chandani Joshi (Regional Programme Director, vii-viii UNIFEM (SARO) ) v. Preface (by Dr. George Mathew, ISS) ix-x vi. Acknowledgements (by Mr. Sankar Sen, ISS) xi-xii vii. From the Researcher’s Desk (by Mr. P.M. Nair, NHRC Nodal Officer) xii-xiv Chapter Title Page No. Reference 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Review of Literature 7-32 3. Methodology 33-39 4. Profile of the study area 40-80 5. Survivors (Rescued from CSE) 81-98 6. Victims in CSE 99-113 7. Clientele 114-121 8. Brothel owners 122-138 9. Traffickers 139-158 10. Rescued children trafficked for labour and other exploitation 159-170 11. Migration and trafficking 171-185 12. Tourism and trafficking 186-193 13. Culturally sanctioned practices and trafficking 194-202 14. Missing persons versus trafficking 203-217 15. Mind of the Survivor: Psychosocial impacts and interventions for the survivor of trafficking 218-231 16. The Legal Framework 232-246 17. The Status of Law-Enforcement 247-263 18. The Response of Police Officials 264-281 19.