The Improvement of Student Teaching Through a Consortium of Greater Cleveland Schools and Colleges. Vol. 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020 SST Building District Level District Region Received Award Winners 1 Bryan Elementary Bryan City Bronze 1 Horizon Science Academy- Springfield Silver 1 Horizon Science Academy- Toledo Bronze 1 Fairfield Elementary Maumee City Schools Bronze 1 Fort Meigs Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Frank Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Hull Prairie Intermediate Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg Junior High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Toth Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Woodland Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Crissey Elementary Springfield Local Schools Bronze 1 Dorr Elementary Springfield Local Schools Silver 1 Old Orchard Elementary Toledo City Schools Bronze 1 Robinson Achievement Toledo City Schools Silver 2 Vincent Elementary School Clearview Local School District Bronze 2 Lorain County Early Learning Center Educational Service Center of Lorain Bronze County 2 Prospect Elementary School Elyria City Schools Bronze 2 Keystone Elementary School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone High School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone Middle School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Midview East Intermediate School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview High School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview Middle School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview North Elementary School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview West Elementary -

ACT-Ohio-PLA-List-Ju

City Client Value Haverhill (Tri-State BTC) Aristech Chemical $100 Million Powell Cleveland (Cleveland BTC) City of Cleveland $300 Million Greenville, Darke County (Dayton BTC) DPL Energy $40 Million Elyria (N. Central Ohio BTC) City of Elyria Lorain Cty (N. Central OH BTC) Lorain Cty. Eastlake (Cleveland BTC) Eastlake Minor league Baseball complex Tri-State BCTC Scioto County Bd of Commissioners $10-12 Million Dayton OH BCTC Global Performance Ironton, Lawrence County Ironton City School Board of Education Akron Board of Ed of Akron Schoold District $10 Million Canton City of Canton Brooklyn / Cleveland OH BCTC Brooklyn Idlewood Properties Portsmouth, Scioto County Washington-Nile Local School Board of Education $16 Million Akron Tri-County BCTC Crystal Clinic/Summa Health Systems Joint Venture $105 Million Cleveland BCTC Cleveland Museum of Art $120 Million Williamson College of Business Administration (Youngstown State Western Reserve BCTC $26.5 Million University) Parkersburg-Marietta BCTC Marietta City School Project $80 Million Western Reserve BCTC Mahoning County Parkersburg-Marietta BCTC Board of Ed of the Switzerland of Ohio Local Schl Dstrct Columbus/Central Ohio BCTC Circleville City School District Tri-County BCTC Schumacher Community Learning Center $11 Million Tri-County BCTC Hyre Community Learning Center $25 Million Tri-County BCTC Buchtel/Perkins Community Learning Center $48 Million Cleveland BCTC Berea City School District North Central Ohio BCTC Ohio School Facilities Commission (OSFC) Western Reserve BCTC Brier Hill -

Parma City School District Cuyahoga County

PARMA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT CUYAHOGA COUNTY SINGLE AUDIT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2005 PARMA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT CUYAHOGA COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE Schedule of Federal Awards Receipts and Expenditures 1 Notes to the Schedule of Federal Awards Receipts and Expenditures 3 Independent Accountants’ Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Required By Government Auditing Standards 5 Independent Accountants’ Report on Compliance with Requirements Applicable to Major Federal Programs and Internal Control Over Compliance in Accordance with OMB Circular A-133 7 Schedule of Findings 9 This page intentionally left blank. PARMA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT CUYAHOGA COUNTY SCHEDULE OF FEDERAL AWARDS RECEIPTS AND EXPENDITURES FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2005 Federal Grantor/ Pass Through Federal Pass Through Grantor Entity CFDA Non-Cash Non-Cash Program Title Number Number Receipts Receipts Disbursements Disbursements U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Passed Through Ohio Department of Education: Child Nutrition Cluster: Food Distribution Program N/A 10.550 $0 $275,904 $0 $275,904 National School Breakfast 044636-05PU-2004 10.553 1,926 0 1,926 0 044636-05PU-2005 5,225 0 5,225 0 Total CFDA 7,151 0 7,151 0 National School Lunch Program 044636-LLP4-2004 10.555 268,033 0 268,033 0 044636-LLP4-2005 685,165 0 685,165 0 Total CFDA 953,198 0 953,198 0 Total U.S. Department of Agriculture - Nutrition Cluster 960,349 275,904 960,349 275,904 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Passed Through Ohio Department of Education: -

Phone # Site Name Contact Person Title & Address Fax Email

Phone # Site Name Contact Person Title & Address Fax Email Albion Middle School Donald Berkey Guidance Counselor 440-572- 11109 Webster Rd, Strongsville, OH 0617 44136 330-636- 3500 AI Root M.S. 333 W. Sturbridge, Medina, OH 44256 Bay Village City Schools Steven Steinhilber Director of Guidance 440-617- 29230 Wolf Rd., Bay Village, OH 44140 440-617-7401 Bay Middle School Tom Groclek 7413 277725 Wolf Rd, Bay Village, OH 44140 440-617- 7600 Carl F. Shuler Middle School Isabel Summers School Counselor 216-471- 13501 Terminal Ave, Cleveland OH 0272 44135 Clearview High School Alicia Howard School Counselor 440-233- 4700 Broadway Ave Lorain, Ohio 6313 EXT. 1313 Cuyahoga Heights Middle Frank Sapara Guidance Counselor 216-429- 4820 East 71st St., Cuyahoga Heights, 216-429-5735 School 5759 OH 44125 Cleveland Hts/Univ. Hts Michael Bailey 216-320- 2155 Miramar Blvd, Univ. Hts, OH 44118 School District 2049 Cleveland Municipal School Kim Petrovich Head 216-634- 3145 W 46th St. Cleveland, OH 44102 1440 216-592-7746 District Kimberly Allen Counselor 2439 Lakeside Ave, Cleveland, OH 44114 Manager 216-592- 7749 Denison Elementary Catherine Ginley Guidance Liasion 216-741- 3799 W. 33rd St. Cleveland OH 44109 2916 Durling Middle School Alicia Howard 440-233- 100 N. Ridge Rd, Lorain, OH, 44052 6864 Euclid Central Middle School Jim Poulson Principal 216-797- 20701 Euclid Ave, Euclid, OH, 44117 216-797-5333 5301 Euclid High School Karen L. Brown Guidance Counselor 711 E.222nd St. OH 44123 Fairview High School Gabriella Bitz 4507 W 213th St, Fairview Park, OH 44126 FDR Middle School Carnetta Cheek Dept. -

AVTT Traveling Vietnam Wall at Tri-C This Month by Jeannie Roberts of Hurt: Between Innocence Mayor Tim Degeeter

Please P “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything”- Dwight D. Eisenhower TAKEFREE! ONE! atronize Our Advertisers Interested In Writing For The Observer? - Join Us At Our Public Meeting At Arabica Coffee House (6285 Pearl Rd.) Every Tuesday 7 PM Proud Member Of The Observer Media Family Of Community Owned Newspapers & Websites Volume 10 • Issue 6 • June, 2018 AVTT Traveling Vietnam Wall At Tri-C This Month by Jeannie Roberts of Hurt: Between Innocence Mayor Tim DeGeeter. “We cifically honors those who gave The American Veterans and Arrogance in Vietnam.” respect and honor those who their lives in the Vietnam War, Traveling Tribute (AVTT) is Sgt. Hack volunteered for have served and are currently and we are humbled to host an 80-percent scale version of Vietnam in 1968, joining the serving in our country’s armed this recognition.” the Vietnam Memorial Wall 1st Infantry Division and was forces. The Traveling Wall spe- in Washington D.C. Across its wounded in Lai Khe in1968, 360-foot length, the wall con- and subsequently awarded the tains every single name etched Purple Heart. He spent a full on the original. The Traveling calls for the truck to arrive at year in a U.S. Army hospital in Wall will arrive in Parma on 5:30 p.m. on Wednesday, June Fort Knox. Wednesday evening, June 27 27 and to be escorted from mile Powell was an Army and will be escorted to the cam- marker 225 on I-71, then north Nurse at the 24th Evacua- pus by the Rolling Thunder, on I-71 to Pearl Road, then to tion Hospital in Long Binh. -

Front Office Directory Brad Mohr

FRONT OfficE DIRECTORY Brad Mohr ................................................................................................ Manager, Baseball Operations Willie Jenks .................................................................................................Visiting Clubhouse Manager OFFICERS Steve Walters .......................................................................................... Coordinator, Ballpark Services Lawrence J. Dolan ................................................................................ Owner & Chief Executive Officer Gloria Carter ........................................................................................... Assistant, Ballpark Operations Paul J. Dolan ............................................................................................................................ President Kenny Campbell ...................................................................................................Main Lobby Reception Mark Shapiro ...................................................................... Executive Vice President, General Manager Louis Pavlick .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Dennis Lehman ................................................................................Executive Vice President, Business Ray Branham .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Victor Gregovits .................................................................... -

Challenging Past Year Gives Way to Summer Optimism

Spring/Summer 2021 Challenging past year gives way to summer optimism By Tim DeGeeter events: Parma Night, Summer Band Concert Series and Movie Night, which will include several nights with the help Last spring when I looked out my of the Parma City School District. We will also unveil the office window, I saw the progress Warrior Fitness Course at James Day Park. that construction workers were making on Ridge Road, but I also Keep in mind that our Recreation Department events and saw a nearly vacant parking lot at other city activities, such as our Independence Day Parade The Shoppes at Parma. Little traffic (this year is Saturday, July 3 because the holiday lands on a meant Ridge would be completed Sunday) all hinge on health department guidelines. I in record time, but it also meant no remain optimistic, however, that we can resume these shoppers at our largest retail and community activities as we gradually return to better and restaurant center. more normal times. To see what is on the calendar for summer and early fall, go to the back page of this It was challenging as we navigated newsletter for a list of upcoming events. a shutdown, heeded the warnings of health officials and faced an uncertain year ahead. Like other mayors As for our Donna Smallwood Activities Center, it was the throughout the country, I worried about the economic first closure we made last year and will be the last to impact, as well as the public health of our community. reopen this year. Meanwhile, the staff continues to prepare and deliver meals to its homebound members, Despite a year like no other, Parma residents pulled assist with senior transportation for important medical together. -

Than 500 Businesses

Updated JUNE 2020 City Guide UNITED STATES // OHIO // CUYAHOGA // CLEVELAND 41° 30′ 35″ N 81° 33′ 48″ W Became a city 1921 | Incorporated as a village 1903 CLEVELAND HEIGHTSL . T E Home to the ARTS A Y L MTICELL Population R 46,238 | 2010 Census & CAIN PARK MAIELD IELD MA Y D. BLV HTS EUCLID More than CET More than 500 CEDA LEE F L AIMUT A 135 Acres Independently owned S. T of Parks Businesses Wide Selection of Home Choices Cleveland Heights is rich in architectural history 54 offering many home styles in virtually any budget Historical Landmarks Winter Lows Summer Highs AVERAGE 22 – 30 °F TEMPERATURE 79 – 83 °F Home to the Inventor (–5 – –1 °C) US CLIMATE DATA (26 – 28 °C) of the Traffic Signal Great Choice of Public, • 10 minutes to University Circle Private & Parochial • 15 minutes to World Class Health Care schooling options • 20 minutes to Downtown Cleveland 8 Higher Education • minutes to 5 Major Interstates Campuses within 20 10 Miles • 40 minutes to Hopkins Airport www.ClevelandHeights.com & www.CHParks.com Important Phone Numbers EMERGENCY Police or Fire ....... 9 - 1 - 1 Police Non-emergency 216/321-1234 Fire Non-emergency 216/321-1212 City Hall Main Number 216/291-4444 City Manager’s Office 216/291-3737 Building Department 216/291-4900 Cain Park (summer only) 216/371-3000 Community Center 216/691-7373 Community Relations 216/291-2323 Finance Department 216/291-3900 Forestry 216/691-7317 Housing Inspections 216/291-5900 Housing Preservation 216/291-4877 Human Resources 216/291-5757 Municipal Court 216/291-4901 Parks and Recreation 216/691-7373 Planning & Development 216/291-4878 Public Relations 216/291-5794 Public Works, Refuse & Recycling 216/691-7300 Senior Activity Center 216/691-7377 Service Department 216/691-7300 Sewer Department 216/291-5995 Cleveland Water 216/664-3130 County Board of Health 216/201-2001 Regional Income Tax (R.I.T.A.) 440/526-0900 Annual City-Wide Events Cain Park Dr. -

Clearing the Path

2020 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY CLEARING THE PATH LETTER FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND CEO College Now’s mission is to increase postsecondary educational attainment hen students first start working with College Now, many cannot envision their postsecondary pathway. Everything MISSION in Greater Cleveland through college and career access advising, financial Wfrom applying to a college, university, or certificate program to thinking about a major and eventual career path aid counseling, and scholarship and retention services. can seem like a daunting task, with obstacles to overcome and challenges to face. Sometimes, those challenges seem insurmountable and their dreams unachievable. At College Now, we work diligently every day to educate our students – of all ages – on the opportunities available to them in postsecondary and beyond. Through our traditional high school advising, scholarships and financial aid, adult programs FINANCIAL RESULTS and services, and the College Now Mentoring Program, we help students navigate the often-complicated path to achieve Operational Revenue Operational Expenses their goals. Ending July 31, 2019 Ending July 31, 2019 College Now has been doing this – clearing the path – for students for over 50 years, starting in 1967 with a small group Foundations $4,203,039 Advising and Counseling Services $7,512,452 of students from the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD). What started as small scholarships for this group (one Corporations $2,211,369 Scholarship Awards $3,775,735 of whom, Philip Thompson, you will read more about later in this report) quickly grew into advising services for students Individuals and Organizations $416,688 Scholarship and Retention Services $1,172,417 throughout the CMSD, then the suburbs and parochial schools, followed by adult advising. -

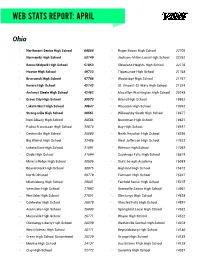

Web Stats Report: April

WEB STATS REPORT: APRIL Ohio 1 Northmont Senior High School 64084 31 Roger Bacon High School 22705 2 Normandy High School 53749 32 Jackson-Milton Local High School 22262 3 Berea-Midpark High School 51853 33 Cleveland Heights High School 22176 4 Hoover High School 49723 34 Tippecanoe High School 21768 5 Brunswick High School 47786 35 Woodridge High School 21747 6 Revere High School 42742 36 St. Vincent-St. Mary High School 21324 7 Amherst Steele High School 42462 37 Massillon Washington High School 20248 8 Grove City High School 39073 38 Hiland High School 19582 9 Lakota West High School 38647 39 Wauseon High School 19342 10 Strongsville High School 38561 40 Willoughby South High School 18677 11 New Albany High School 36506 41 Boardman High School 18631 12 Padua Franciscan High School 35874 42 Bay High School 18557 13 Centerville High School 35080 43 North Royalton High School 18295 14 Big Walnut High School 33406 44 West Jefferson High School 17623 15 Lakota East High School 31891 45 Rittman High School 17063 16 Clyde High School 31594 46 Cuyahoga Falls High School 16874 17 Mineral Ridge High School 30505 47 Saint Joseph Academy 16083 18 Beavercreek High School 30075 48 Highland High School 15672 19 North Olmsted 29779 49 Fairmont High School 15327 20 Miamisburg High School 29641 50 Fairfield Senior High School 15275 21 Vermilion High School 27992 51 Greenville Senior High School 14967 22 Westlake High School 27851 52 Olentangy High School 14828 23 Coldwater High School 26879 53 Olmsted Falls High School 14597 24 Avon Lake High School -

FINAL REPORT Countywide All Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan For

FINAL REPORT Countywide All Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan for Cuyahoga County Prepared for Cuyahoga County Emergency Services Cuyahoga County, Ohio December 2003 Countywide All Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Cuyahoga County, Ohio TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CUYAHOGA COUNTY NATURAL DISASTER BACKGROUND ....................................................... 1 2.0 COUNTY INFORMATION ..................................................................................................... 3 2.1 CUYAHOGA COUNTY PROFILE AND COMMUNITY INFORMATION ............................................... 3 Cleveland Metroparks ............................................................................................................ 3 Watershed Organizations ...................................................................................................... 6 Chagrin Region ...................................................................................................................... 7 1. Hunting Valley ............................................................................................................... 7 2. Woodmere Village ......................................................................................................... 7 3. Orange Village .............................................................................................................. 8 4. Moreland Hills .............................................................................................................. -

Varsity Baseball (Boys) Spring 2020-2021

Fairview High School 4507 213Th St Fairview Park, OH 44126 School Phone: 440-356-3500 Fax: 440-356-3529 Email: [email protected] Superintendent Principal Athletic Director Athletic Director Dr. Bill Wagner Christopher J. Vicha Joe Dianetti Joe Dianetti Varsity Baseball (Boys) Spring 2020-2021 Day Date Opponent Place Time S Monday Mar. 22 North Olmsted High School Fairview High School 4:30PM S Thursday Mar. 25 Brookside High School Fairview High School 5:00PM Saturday Mar. 27 @ Brooklyn Middle/High School Brooklyn Middle/High School 11:00AM Monday Mar. 29 @ Midview High School Midview High School 5:00PM Thursday Apr. 01 Lakewood HS-Lakewood Fairview High School 4:30PM Saturday Apr. 03 Columbian High School Fairview High School 1:00PM Monday Apr. 05 @ Lakewood HS-Lakewood Lakewood HS-Lakewood 4:30PM Tuesday Apr. 06 @ Buckeye High School(Medina) Buckeye High School(Medina) 5:00PM Thursday Apr. 08 Buckeye High School(Medina) Fairview High School 5:00PM Saturday Apr. 10 @ Open Door Christian Schools Open Door Christian Schools 11:00AM Monday Apr. 12 @ Bay High School Bay High School 5:00PM Tuesday Apr. 13 Bay High School Fairview High School 4:30PM Thursday Apr. 15 Valley Forge High School Fairview High School 5:00PM Friday Apr. 16 @ OPEN (Cleveland Indians OPEN TBA Charities Hardball Classic @ Progressive Field) Monday Apr. 19 @ Valley Forge High School Valley Forge High School 5:00PM Tuesday Apr. 20 Holy Name High School Fairview High School 4:30PM Thursday Apr. 22 @ Holy Name High School Holy Name High School 5:00PM Friday Apr. 23 Lutheran HS West Fairview High School 7:00PM Monday Apr.