DSWA Dorset News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As the Upkeep Bomb Was Not Only a Different Shape to Contemporary

CARRYING UPKEEP As the Upkeep bomb was not only a different shape to contemporary bombs but also had to be spun before release, Barnes Wallis and Vickers-Armstrongs had to come up with a purpose built mounting to be fitted to the Type 464 Lancasters. This section was the most significant and important of all the Type 464 modifications, yet due to its position, in shadow under the black painted belly of the Lancaster, it has never clearly been illustrated before. 14 15 starboard front port rear the calliper arms The four calliper arms were made of cast aluminium with the connecting piece at the apex made of machined steel. Each apex piece contained a circular hub upon which the Upkeep would be suspended. The four arms were attached to the fuselage by heavy duty brackets which allowed the arms to rotate freely outwards to allow a clean release of the bomb. To load the Upkeep, the arms were closed onto it and retained in that position by means of a heavy-duty cable in an inverted ‘Y’ shaped form, with each of the V shaped lengths being connected to one of the front calliper arms, while the stem was attached to a standard 4000lb ‘Type F’ bomb release unit. After the arms were closed, the threaded ends of the cables were fitted through eyelets in the front calliper arms, and retained in position by large bolts, which also allowed for some adjustment and tensioning. 16 17 port front starboard spinning the Upkeep To enable the Upkeep to be spun, A Vickers Variable Speed Gear (VSG) unit was installed forward of the calliper arms and securely bolted to the roof of the bomb bay. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

3.1 the Dambusters Revisited

The Dambusters Revisited J.L. HINKS, Halcrow Group Ltd. C. HEITEFUSS, Ruhr River Association M. CHRIMES, Institution of Civil Engineers SYNOPSIS. The British raid on the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams on the night of 16/17 May, 1943 caused the breaching of the 40m high Möhne and 48m high Eder dams and serious damage to the 69m high Sorpe dam. This paper considers the planning for the raid, model testing, the raid itself, the effects of the breaches and the subsequent rehabilitation of the dams. Whilst the subject is of considerable historical interest it also has significant contemporary relevance. Events following the breaching of the dams have been used for the calibration of dambreak studies and emphasise the vulnerability of road and railway bridges which is not always acknowledged in contemporary studies. INTRODUCTION In researching this paper the authors have been very struck by the human interest in the story of English, German and Ukrainian people, whether civilian or in uniform, who participated in some aspect of the raid or who lost their lives or homes. As befits a paper for the British Dam Society, this paper, however, concentrates on the technical questions that arise, leaving the human story to others. This paper was prompted by the BDS sponsored visit, in April 2009, to the Derwent Reservoir by 43 members of the Association of Friends of the Hubert-Engels Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Applied Hydromechanics at Dresden University of Technology. There is a small museum at the dam run by Vic Hallam, an employee of Severn Trent Water. -

S I D M O U T H

S I D M O U T H Newsletter September 2017 Issue 48 From the Chairman I closed my piece in the last newsletter by wishing you a great summer unfortunately that has now passed and, according to the met office, we are now officially in Autumn! One of the "hot topics" for the last newsletter was the proposed takeover of the lease of St Francis Church Hall by the Sidmouth Town Band, this has been delayed with no further developments likely until December this year. I'm confident that many organisations, apart from the U3A, hope that the layout of the hall does not change regardless of who operates the lease. It is with some sadness that I've learnt of the passing of Joy Pollock, a founder member of Sidmouth U3A. Joy along with Madge White and June Newbould were the three ladies who met at the Sidmouth Sports Centre and decided to create a steering committee to set-up a U3A branch in Sidmouth. That small seed planted in October 1993 with 15 members has blossomed into our present branch with approaching 350 members. The original membership fee was £5 per head but interestingly the attendance charge for a monthly meeting was 50p the same as it is today! The U3A which Joy helped to start was very different to the organisation we have today, however, when Joy attended the anniversary lunch in 2014 she seemed to approve of the way the branch had developed. There will be those who remember Joy and mourn the passing of one our founder members. -

Airships Over Lincolnshire

Airships over Lincolnshire AIRSHIPS Over Lincolnshire explore • discover • experience explore Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum 2 Airships over Lincolnshire INTRODUCTION This file contains material and images which are intended to complement the displays and presentations in Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum’s exhibition areas. This file looks at the history of military and civilian balloons and airships, in Lincolnshire and elsewhere, and how those balloons developed from a smoke filled bag to the high-tech hybrid airship of today. This file could not have been created without the help and guidance of a number of organisations and subject matter experts. Three individuals undoubtedly deserve special mention: Mr Mike Credland and Mr Mike Hodgson who have both contributed information and images for you, the visitor to enjoy. Last, but certainly not least, is Mr Brian J. Turpin whose enduring support has added flesh to what were the bare bones of the story we are endeavouring to tell. These gentlemen and all those who have assisted with ‘Airships over Lincolnshire’ have the grateful thanks of the staff and volunteers of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum. Airships over Lincolnshire 3 CONTENTS Early History of Ballooning 4 Balloons – Early Military Usage 6 Airship Types 7 Cranwell’s Lighter than Air section 8 Cranwell’s Airships 11 Balloons and Airships at Cranwell 16 Airship Pioneer – CM Waterlow 27 Airship Crews 30 Attack from the Air 32 Zeppelin Raids on Lincolnshire 34 The Zeppelin Raid on Cleethorpes 35 Airships during the inter-war years -

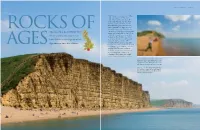

Agesalmost As Old As Time Itself, the West Dorset Coastline Tells Many

EXPLORING BRITAIN’ S COASTLINE H ERE MAY BE DAYS when, standing on the beach at TCharmouth, in the shadow of the cliffs behind, with the spray crashing against the shore and the wind whistling past your ears, it is ROCKS OF hard to imagine the place as it was 195 million years ago.The area was Almost as old as time itself, the west a tropical sea back then, teeming with strange and wonderful creatures. It is Dorset coastline tells many stories. a difficult concept to get your head around but the evidence lies around Robert Yarham and photographer Kim your feet and in the crumbling soft mud and clay face of the cliffs. AGES Disturbed by the erosion caused by Sayer uncover just a few of them. the spray and wind, hundreds of small – and very occasionally, large – fossils turn up here.The most common fossils that passers-by can encounter are ammonites (the curly ones), belemnites (the pointy ones); and, rarely, a few rarities surface, such as ABOVE Locals and tourists alike head for the beaches by Charmouth, where today’s catch is a good deal less intimidating than the creatures that swam the local seas millions of years ago. MAIN PICTURE The layers of sand deposited by the ancient oceans can be clearly seen in the great cliffs of Thorncombe Beacon (left) and West Cliff, near Bridport. A37 A35 A352 Bridport A35 Dorchester Charmouth A354 Lyme Regis Golden Cap Abbotsbury Osmington Mills Swannery Ringstead Bay The Fleet Weymouth Chesil Beach Portland Harbour Portland Castle orth S N I L 10 Miles L Isle of Portland O H D I V A The Bill D icthyosaurs or plesiosaurs – huge, cottages attract hordes of summer predatory, fish-like reptiles that swam visitors.They are drawn by the the ancient seas about 200 million picturesque setting and the famous years ago during the Jurassic period. -

The Dams Raid

The Dams Raid An Air Ministry Press Release, dated Monday, 17th May 1943, read as follows: In the early hours of this (Monday) morning a force of Lancasters of Bomber Command led by Wing Commander G. P. Gibson, D.S.O, D.F.C., attacked with mines the dams at the Möhne and Sorpe reservoirs. These control two-thirds of the water storage capacity of the Ruhr basin. Reconnaissance later established that the Möhne Dam had been breached over a length of 100 yards and that the power station below had been swept away by the resulting floods. The Eder Dam, which controls head waters of the Weser and Fulda valleys and operates several power stations, was also attached and was reported as breached. Photographs show the river below the dam in full flood. The attacks were pressed home from a very low level with great determination and coolness in the face of fierce resistance. Eight of the Lancasters are missing. That short statement lacked some of the secret details and the full human story behind one of the most famous raids in the history of the Royal Air Force. It is the real story of the Dambusters. The story of the “bouncing bomb” designer Barnes Wallis and 617 Squadron is heavily associated with the film, starring Michael Redgrave as Dr Barnes Wallis and Richard Todd as Wing Commander Guy Gibson – and featuring the Dambusters March, the enormously popular and evocative theme by Eric Coates. The film opened in London almost exactly twelve years after the events portrayed. The main detail of the raid which was not fully disclosed until much later was the true specification of the bomb, details which were still secret when the film was made. -

Dorsetguidebook.Com

Welcome to Dorset Durdle Door on the Purbeck coast is an iconic symbol of Dorset DORSET is situated in south- The combination of a benign bour and the vast area of coun- west England on the the Eng- climate, wonderful coastal tryside to explore, Dorset rare- lish Channel coast. It covers an scenery, unspoilt countryside ly feels busy, especially away area of 1,024mi2 (2,653km2) and nearby urban areas has from the main attractions. and stretches about 60mi made tourism the main indus- (96km) from west to east and try in Dorset. Its popularity The oldest evidence for the 45mi (72km) from north to first developed in the late 18th presence of people is Palaeo- south. With no motorways century when the fashion for lithic handaxes from 400,000 and few dual carriageways the bathing in the sea and taking years ago. The county has been roads tend to be slow if busy. seaside holidays started. continuously inhabited since c.11,000BC when the first The total population of the Today nearly 4 million people Mesolithic hunter-gatherers county including the Unitary visit the county for a week or arrived after the last glaciation. Authorities was 763,700 in more and a further 21 mil- the 2011 census. Bourne- lion take day trips. Of these Since then Neolithic, Bronze mouth and Poole together had c.58% go to the towns, c.26% and Iron Age cultures flour- 331,600 people, while the Dor- to the coast and only c.16% to ished. Romans, Saxons, Vi- set County Council non-met- the rural interior. -

Jurassic Coast Challenge 22/23 May 2021

Jurassic Coast Challenge 22/23 May 2021 Final Event Guide The 2021 Jurassic Coast Challenge is approaching quickly, and with about 2,000 people taking part – it should be a great event! This ‘Final Event Guide’ will help with your final planning, and please read this alongside other material set out in the in the ‘App’ or in the Participant Area of the Ultra Challenge website. With official Covid rules & regulations in place – you will of course see appropriate risk reduction measures throughout the event – and you’ll also be required to make a formal ‘Covid Screening Declaration’ prior to the event. CHALLENGE APP Download the APP for access to key info & updates. Available in both the Apple or Google Stores, search 'Action Challenge' and download. Use the code AC1 to get started on the front screen – then go to 'load challenge' in the menu and enter the code JCC – which downloads the info for The Jurassic Coast Challenge. The App gets updates in the lead up to the Challenge, including maps & special features to use whilst on the actual event - so make sure you have it on your phone! In the APP you will find: ‘Need to Know’ list – all the info! Merchandise shop Travel advice Optional Extras booking Route Maps – rest stop info Kit Lists + Much More ..... We also have a Participant Area on the website that holds some of the key info: https://ultrachallenge.com/participant-area/jurassic-coast-participant-area/ KEY PRE-EVENT INFO.... Start times For anyone registered before 21 April 2021, you should have received your allocated start time sent via EMAIL on Wed 21st April (+ a text alert). -

Abbotsbury Walks

DISCOVERING ABBOTSBURY An Introduction to the Village and some Short Village Walks Prepared by Chris Wade & Peter Evans The Friends of St Nicholas Abbotsbury Time-line 170* Jurassic coast formed million 100 years Chesil Beach created ago 50 Abbotsbury fault occurred, creating the The Friends of St Nicholas Ridgeway to the north of the village 6000 BC* First evidence of hunters / gatherers ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: around the Fleet We would like to thank The Friends of St Nicholas for financing 500 BC* Iron Age fort built on ridge this booklet, the profits from which will help to maintain 44 AD Roman invasion of Great Britain began – the fabric of the church. We also thank the following for first mill built here photographs/illustrations: 6th C A Chapel built here by Bertulfus? Mrs Francesca Radcliffe 1023 King Canute gave land, including Mr Torben Houlberg Portesham & Abbotsbury, to Orc Mrs Christine Wade 1044 Abbey built Mr Peter Evans Mr Andrew King 14th C Church of St Nicholas, Tithe Barn & Mr Eric Ricketts - St Catherine’s Chapel illustration published by permission The Dovecote Press 1540’s Abbey destroyed (Henry VIII), first Manor House built USEFUL LINKS 1644 Manor House burned down in Civil War www.abbotsbury.co.uk 1672 First non-conformist meeting place Abbotsbury village website, info on businesses including arts, established in Abbotsbury crafts, galleries, tea rooms, restaurants & accommodation. 1765 Second Manor House built overlooking www.abbotsbury.co.uk/friends_of_st_nicholas Chesil Beach Friends of St Nicholas website 1890’s Railway opened – for iron ore mining initially, then tourism www.abbotsbury-tourism.co.uk The Abbotsbury Swannery, Subtropical Gardens and the Tithe 1913 Second Manor House burned down, third Barn (Childrens’ Farm). -

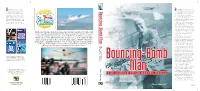

Bouncing-Bomb Man

r Iain Murray is a lecturer in arnes Wallis is best known as the the School of Computing at the ‘boffin’ behind the famous bouncing D Bouncing B University of Dundee, where his bomb used by 617 Squadron to breach research interests include emotion the Ruhr dams in 1943, but his work in synthesised speech. He is Chair covers a far wider canvas. It ranges of the Tayside & Fife Branch of the from airships, through novel aircraft British Science Association and acted structures and special weapons to as a consultant for an episode of the long-range supersonic aircraft, and an ITV drama series Foyle’s War, which extensive patent portfolio. featured a group working on the So how did Wallis’s engineering ‘bouncing bomb’. He lives in Dundee. brilliance take ideas from airships and push them forward to create aircraft - faster than Concorde? Dr Iain Murray Bomb Man Bomb describes the huge breadth of Wallis’s work, showing why his genius brought totally new ideas into these fields, and From giant airships, hypersonic passenger aircraft and a better cricket ball reveals the science and engineering to the legendary bouncing bomb, this fascinating book examines the work expertise that he deployed to make them work. of British engineering genius Sir Barnes Wallis. Dr Iain Murray analyses This is the first book to describe Wallis’s ideas as he did himself – like an experiment, to be invented, built the entire life’s work of Wallis in detail, viewed through the prism of his and tested in operation. He looks at the huge range of Wallis’s inventions technical achievements. -

Geological Sights! Southwest England Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society

Geological Sights! Southwest England Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society @GeolAssoc Geologists’ Association www.geologistsassociation.org.uk Southwest England Triassic Mercia Mudstone & Penarth Groups (red & grey), capped with Early Jurassic Lias Group mudstones and thin limestones. Aust Cliff, Severn Estuary, 2017 Triassic Mercia Mudstone & Penarth Groups, with Early Jurassic Lias Group at the top. Looking for coprolites Gypsum at the base Aust Cliff, Severn Estuary, 2017 Old Red Sandstone (Devonian) Portishead, North Somerset, 2017 Carboniferous Limestone – Jurassic Inferior Oolite unconformity, Vallis Vale near Frome Mendip Region, Somerset, 2014 Burrington Oolite (Carboniferous Limestone), Burrington Combe Rock of Ages, Mendip Hills, Somerset, 2014 Whatley Quarry Moon’s Hill Quarry Carboniferous Limestone Silurian volcanics Volcaniclastic conglomerate in Moon’s Hill Quarry Mainly rhyodacites, andesites and tuffs - England’s only Wenlock-age volcanic exposure. Stone Quarries in the Mendips, 2011 Silurian (Wenlock- age) volcaniclastic conglomerates are seen here above the main faces. The quarry’s rock types are similar to those at Mount St Helens. Spheroidal weathering Moons Hill Quarry, Mendips, Somerset, 2011 Wave cut platform, Blue Lias Fm. (Jurassic) Kilve Mercia Mudstone Group (Triassic) Kilve St Audrie’s Bay West Somerset, 2019 Watchet Blue Lias Formation, Jurassic: Slickensiding on fault West Somerset, 2019 Triassic, Penarth Group Triassic, Mercia Mudstone Blue Anchor Fault, West Somerset, 2019 Mortehoe, led by Paul Madgett. Morte Slates Formation, Devonian (Frasnian-Famennian). South side of Baggy Point near Pencil Rock. Ipswichian interglacial dune sands & beach deposit (125 ka) upon Picton Down Mudstone Formation (U. Devonian) North Devon Coast, 1994 Saunton Down End. ‘White Rabbit’ glacial erratic (foliated granite-gneiss). Baggy Headland south side.