Italy Failed the Test | International Affairs at LSE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objection Résolution Di ECR “Lead Gunshot in Or Around Wetlands”- Risultati Votazione Per Appello Nominale

Objection Résolution di ECR “Lead gunshot in or around Wetlands”- Risultati votazione per appello nominale Favorevoli 292 + ECR Aguilar, Sergio Berlato (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia), Buxadé Villalba, de la Pisa Carrión, Dzhambazki, Eppink, Carlo Fidanza (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Pietro Fiocchi (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Raffaele Fitto (FRATELLI D’ITALIA - Intergruppo Caccia ) , Geuking, Kempa, Lundgren, Nicola Procaccini (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Rooken, Roos, Ruissen, Slabakov, Raffaele Stancanelli (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) Stegrud, Terheş, Tertsch, Tomaševski, Tomašić, Tošenovský, Vondra, Vrecionová, Weimers, Zahradil GUE/NGL: Konečná, MacManus ID: Matteo Adinolfi (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia) , Anderson, Androuët, Annemans, Simona Baldassarre (LEGA), Bardella , Alessandra Basso (LEGA), Bay, Beck, Berg, Bilde, Mara Bizzotto (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Blaško, Anna Cinzia Bonfrisco (LEGA), Paolo Borchia (LEGA), Buchheit, Marco Campomenosi, (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Massimo Casanova (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) ; Susanna Ceccardi (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Angelo Ciocca (LEGA), Collard, Rosanna Conte (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia) , Gianantonio Da Re, (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) David, De Man, Francesca Donato (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Marco Dreosto (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Fest, Gianna Gancia (LEGA), Garraud, Grant, Griset, Haider, Hakkarainen, Huhtasaari, Jalkh, Jamet, Juvin, Krah, Kuhs, Lacapelle, Oscar Lancini (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Laporte, Lebreton, -

The Hidden Cost of September 11 Liz Fekete

Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete A special issue of the European Race Bulletin Globalisation has set up a monolithic economic system; September 11 threatens to engender a monolithic political culture. Together, they spell the end of civil society. – A. Sivanandan, Director, Institute of Race Relations Institute of Race Relations 2-6 Leeke Street, London WC1X 9HS Tel: 020 7837 0041 Fax: 020 7278 0623 Web: www.irr.org.uk Email: [email protected] Liz Fekete is head of European research at the Insitute of Race Relations where she edits the European Race Bulletin. It is published quarterly and available on subscription from the IRR (£10 for individuals, £25 for institutions). •••••• This report was compiled with the help of Saba Bahar, Jenny Bourne, Norberto Laguia Casaus, Barry Croft, Rhona Desmond, Imogen Forster, Haifa Hammami, Lotta Holmberg, Vincent Homolka, Mieke Hoppe, Fida Jeries, Simon Katzenellenbogen, Virginia MacFadyen, Nitole Rahman, Hazel Waters, and Chris Woodall. Special thanks to Tony Bunyan, Frances Webber and Statewatch. © Institute of Race Relations 2002 ISBN 085001 0632 Cover Image by David Drew Designed by Harmit Athwal Printed by Russell Press Ltd European Race Bulletin No. 40 Contents Introduction 1 1. The EU approach to combating terrorism 2 2. Removing refugee protection 6 3. Racism and the security state 10 4. Popular racism: one culture, one civilisation 16 References 22 European Race Bulletin No. 40 Introduction ollowing the events of September 11, it became commonplace to say that the world would Fnever be the same again. -

European Parliament Mid-Term Election: What Impact on Migration Policy?

www.epc.eu 16 March 2017 01/12/2009 European Parliament mid-term election: what impact on migration policy? Marco Funk As the dust settles from the European Parliament’s (EP) mid-term election held on 17 January 2017, migration continues to top the EU’s agenda. The election of Antonio Tajani to replace Martin Schulz as president of the EP brought the institution under the leadership of the European People’s Party (EPP) after a power-sharing agreement with the socialist S&D was cancelled and replaced by a last-minute deal with the liberal ALDE group. A closer look at Tajani’s election and associated reshuffle of key internal positions suggests little change in the EP’s course on migration in the short term. However, upcoming developments may significantly change Parliament dynamics in the longer term. New president, different style Antonio Tajani is considered by many to be a less political, less activist president compared to Martin Schulz. The former is also apparently less willing to insist on a prominent role for the EP than the latter. Furthermore, Tajani shares the same conservative political affiliation as the heads of the European Commission and European Council, which makes ideological confrontations with Jean-Claude Juncker and Donald Tusk even less likely than under Schulz, who had few disagreements with either. While Schulz already maintained good relations with Juncker and closely coordinated responses to the large influx of refugees in 2015/2016, Tajani is even better placed to cooperate effectively due to his previous Commission experience and ideological alignment. Despite Tajani’s association with Italy’s populist conservative leader Silvio Berlusconi, he has adopted a more mainstream conservative political identity, which ultimately won him the EPP’s support. -

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Silvio Is Back: Understanding Berlusconi's Latest Revival Ahead of the Italian

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Silvio is back: Understanding Berlusconi’s latest revival ahead of the Italian general election Page 1 of 3 Silvio is back: Understanding Berlusconi’s latest revival ahead of the Italian general election Despite currently being banned from holding office, Silvio Berlusconi is well placed to have a key role in the Italian general election in March. Fabio Bordignon outlines the factors behind his latest comeback, and how his Forza Italia party could play a central part in the formation of the next Italian government. In the past when we Italian scholars of political science met our colleagues at international conferences, it was always the same question: why Berlusconi? How could a media tycoon, facing multiple-trials and allegations, an unlikely politician later known for his ‘bunga bunga’ parties, have become the leading figure in one of the largest western democracies? The astonishment of the international observer was particularly acute in 2011, when Berlusconi, hit by personal scandals and by the Eurozone debt crisis, resigned as prime minister. Now the world has changed, and it’s full of Berlusconi-style politicians. But at a time when political leaders seem to fade as fast as they rise, Berlusconi is still there. The ‘Eternal Leader’ has survived the collapse of his last government, a ban from the Italian Parliament, and a seemingly irreversible electoral (and personal) decline. And now the 81-year-old leader is ready for a new comeback. He cannot be a candidate, but he still leads (owns) his personal party, Forza Italia. And he could win with his centre-right coalition at the Italian general election in March. -

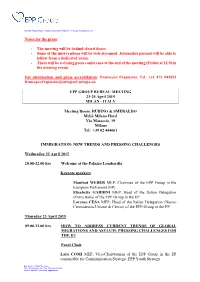

Programme of the Meeting and Press Accreditation Information

Parliamentary Works - Parlamentarische Arbeiten - Travaux Parlementaires Notes for the press: - The meeting will be behind closed doors. - Some of the interventions will be web-streamed. Journalists present will be able to follow from a dedicated room. - There will be a closing press conference at the end of the meeting (Friday at 12.30 in the meeting room). For information and press accreditation: Francesco Frapiccini, Tel: +32 473 941652 [email protected] EPP GROUP BUREAU MEETING 23-24 April 2015 MILAN - ITALY Meeting Room: RUBINO & SMERALDO Meliá Milano Hotel Via Masaccio, 19 Milano Tel: +39 02 444061 IMMIGRATION: NEW TRENDS AND PRESSING CHALLENGES Wednesday 22 April 2015 20.00-22.00 hrs Welcome at the Palazzo Lombardia Keynote speakers Manfred WEBER MEP, Chairman of the EPP Group in the European Parliament (EP) Elisabetta GARDINI MEP, Head of the Italian Delegation (Forza Italia) of the EPP Group in the EP Lorenzo CESA MEP, Head of the Italian Delegation (Nuovo Centrodestra-Unione di Centro) of the EPP Group in the EP Thursday 23 April 2015 09.00-11.00 hrs HOW TO ADDRESS CURRENT TRENDS OF GLOBAL MIGRATIONS AND ASYLUM: PRESSING CHALLENGES FOR THE EU Panel Chair Lara COMI MEP, Vice-Chairwoman of the EPP Group in the EP responsible for Communication Strategy, EPP Youth Strategy Rue Wiertz - B-1047 Bruxelles Tel: +32 (2) 284.21.11 - Fax: +32 (2) 230.97.93 Internet address: http://www.eppgroup.eu Rob WAINWRIGHT, Director of Europol Pier Ferdinando CASINI, President of the International Centre Democratic Party -

Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies

The London School of Economics and Political Science Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies Giulia Pastorella A thesis submitted to the European Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, February 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 86852 words, excluding bibliography, appendix and annexes. Statement of joint work Chapter 3 is based on a paper co-authored with Christopher Wratil. I contributed 50% of this work. 2 Acknowledgements This doctoral thesis would have not been possible without the expert guidance of my two supervisors, Professor Sara Hobolt and Doctor Jonathan White. Each in their own way, they have been essential to the making of the thesis and my growth as an academic and as an individual. I would also like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for their generous financial support of my doctoral studies through their scholarship. -

Activity Report 2011 Centre for European Studies

Our CES Team Credits Activity Report 2011 Centre for European Studies Editors: José Luis Fontalba, Ana María Martín, John Lageson, Erik Zolcer, Rodrigo Castro Publication design: Andreas Neuhaus | PEPATO–GROUP Brussels, December 2011 Centre for European Studies Rue du Commerce 20 B–1000 Brussels The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP) dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. © Centre for European Studies 2012 Photos used in this publication: © Centre for European Studies 2012 The European Parliament assumes no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Table of Contents 04 Welcome 06 About us Executive Board (08) Academic Council (10) Research Associates (12) Staff 2011 (14) Visiting Fellows (15) Internships (16) Individual Members (17) CES Member Foundations (18) 20 Research and Publications · Research Research Papers (22) CES Watch and Policy Briefs (24) CES Flashes (25) · Regular Publications European View (26) European Factbook (27) · Collaborative Publications (28) · Other Publications (30) 32 Events · Our Events Economic Ideas Forum (34) International Visitors Programme (38) The Arab Spring Programme (40) 2nd Transatlantic Centre-Right Think Tank Conference (42) NEW ACTIVITY! CES Authors Dinner (44) Freedom in the Days of the Internet (46) Integration -

Reuters Euro Zone Summit 2013

REUTERS EURO ZONE SUMMIT 2013 An illuminated euro sign is seen in front of the headquarters of the European Central Bank (ECB) in the late evening in Frankfurt January 8, 2013. REUTERS/ KAI PFAFFENBACH The Euro Zone Crisis is Back ollowing a fractured Italian election result the mour and creating the conditions for the crisis to flare heat is back on the Euro Zone with its auster- up again. Could that be spur to galvanise policymakers Fity mantra offering little to douse growing so- again, following signs they have soft-pedalled on closer cial unease in southern Europe. The European Central economic integration and building a banking union in Bank’s pledge to do whatever it takes to save the euro recent months? The Reuters Euro Zone Summit held took some heat out of the debt crisis but unless Italy over four days in Brussels, Frankfurt, Paris, Madrid and can establish a durable, reform-minded government London pressed a dozen of Europe’s top policymakers it might have put itself outside the ECB’s protection, on their plans, hopes and fears and whether they expect opening a dangerous chink in the currency bloc’s ar- the ECB to have to back up its words with actions. 1 REUTERS EURO ZONE SUMMIT 2013 EU’s Barroso urges leaders to stick to austerity goals BY LUKE BAKER AND MICHAEL STOTT The result leaves the euro zone’s third BRUSSELS, FEBRUARY 26, 2013 largest economy facing an extended period of political uncertainty, with the prospect of uropean Commission President Jose another round of elections if a government Manuel Barroso appealed to EU cannot be formed. -

Islam Councils

THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Peter O’Brien THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Political Controversies and Public Philosophies TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2016 by Temple University—Of Th e Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2016 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: O’Brien, Peter, 1960– author. Title: Th e Muslim question in Europe : political controversies and public philosophies / Peter O’Brien. Description: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania : Temple University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: LCCN 2015040078| ISBN 9781439912768 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912775 (paper : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912782 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Europe—Politics and government. | Islam and politics—Europe. Classifi cation: LCC D1056.2.M87 O27 2016 | DDC 305.6/97094—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040078 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Andre, Grady, Hannah, Galen, Kaela, Jake, and Gabriel Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Clashes within Civilization 1 2 Kulturkampf 24 3 Citizenship 65 4 Veil 104 5 Secularism 144 6 Terrorism 199 7 Conclusion: Messy Politics 241 Aft erword 245 References 249 Index 297 Acknowledgments have accumulated many debts in the gestation of this study. Arleen Harri- son superintends an able and amiable cadre of student research assistants I without whose reliable and competent support this book would not have been possible. -

«Poor Family Name», «Rich First Name»

ENCIU Ioan (S&D / RO) Manager, Administrative Sciences Graduate, Faculty of Hydrotechnics, Institute of Construction, Bucharest (1976); Graduate, Faculty of Management, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest (2003). Head of section, assistant head of brigade, SOCED, Bucharest (1976-1990); Executive Director, SC ACRO SRL, Bucharest (1990-1992); Executive Director, SC METACC SRL, Bucharest (1992-1996); Director of Production, SC CASTOR SRL, Bucharest (1996-1997); Assistant Director-General, SC ACRO SRL, Bucharest (1997-2000); Consultant, SC GKS Special Advertising SRL (2004-2008); Consultant, SC Monolit Lake Residence SRL (2008-2009). Vice-President, Bucharest branch, Romanian Party of Social Solidarity (PSSR) (1992-1994); Member of National Council, Bucharest branch Council and Sector 1 Executive, Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSDR) (1994-2000); Member of National Council, Bucharest branch Council and Bucharest branch Executive and Vice-President, Bucharest branch, Social Democratic Party (PSD) (2000-present). Local councillor, Sector 1, Bucharest (1996-2000); Councillor, Bucharest Municipal Council (2000-2001); Deputy Mayor of Bucharest (2000-2004); Councillor, Bucharest Municipal Council (2004-2007). ABELA BALDACCHINO Claudette (S&D / MT) Journalist Diploma in Social Studies (Women and Development) (1999); BA (Hons) in Social Administration (2005). Public Service Employee (1992-1996); Senior Journalist, Newscaster, presenter and producer for Television, Radio and newspaper' (1995-2011); Principal (Public Service), currently on long -

Abolizione Dell'imu Per La Prima Casa

COMUNE DI FONDI (provincia di Latina) ORIGINALE Delibe~onen. 13 del 27/312013 VERBALE DI DELmERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE Adunanza straordinaria di I convocazione - seduta pubblica Oggetto: Mozione per l'abolizione dell'IMU per la prima casa L'anno duemilatredici, adcli ventisette del mese di mano alle ore 9,43 nella sala delle adunanze consiliari Previa l'osservanza di tutte le formalità prescritte dalla vigente legge comunale e provinciale, vennero oggi convocati a seduta i componenti del Consiglio Comunale neIl e persone d el•. sl~.n: Presente Assente 1) Salvatore De Meo Sindaco l 2) Parisella Piero Componente 2 3) Trani Giovanni Componente 1 4) La Rocca Guido Componente 3 5) Sansoni Alessandro Componente 4 6) Carnevale Marco Antonio Componente 5 7) Corina Luigi Componente 2 8) Mattei Vincenzo Componente 6 9) Leone Oronzo Componente 3 lO) Muccitelli Roberta Componente 7 11) Ref"mi Vincenzo Componente 8 121 Paparello Elio Componente 9 13) Spagnardi Claudio Componente lO 14) Saccoccio Carlo Componente 4 15) Coppa Biagio Componente Il 16) Gentile Sergio Componente 12 17) Giuliano Elisabetta Componente 13 18) Marino Maria Luigia Componente 14 19) Di Manno Giulio Cesare Componente 15 20) Cima Maurizio Vincenzo Componente 16 21) Cardinale Franco Componente 5 22) Fiore Giorgio Componente 6 23) Turchetta El!idio Componente 17 24) Padula Claudio Componente 7 25) Forte Antonio Componente 18 26) Paparello Maria Civita Componente 19 27) Faiola Arnaldo Componente 8 28) Fiore Bruno Componente 20 29) Di Manno Giancarlo Componente 21 30) De Luca Luil!i Componente 22 31) Trani Vincenzo Rocco Componente 9 ASSIste il segretarIO generale don. -

Download File

POLITICAL FUNDING REGULATIONS IN LATIN AMERICA: UNCERTAINTY, EQUITY AND TRANSPARENCY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ángel E. Álvarez Michael Coppedge, Director Graduate Program in Political Science Notre Dame, Indiana November 2011 © Copyright by ANGEL E. ALVAREZ 2011 All rights reserved POLITICAL FUNDING REGULATIONS IN LATIN AMERICA: UNCERTAINTY, EQUITY AND TRANSPARENCY Abstract by Angel E. Alvarez Why do self-interested legislators regulate their own finances, allocate public money to minority parties and candidates, impose disclosure rules on politicians‘ financial accounts, and establish penalties for violations of financial regulations? The simplest answer is that politicians regulate political funding to enhance their chances of winning elections. Form this point of view, campaign and party funding rules would be always aimed at providing financial advantages for majority parties and to hinder financial activities of minority parties. The answer is consistent with the mainstream political science literature, but it misses the point that politicians and political parties need money not only to win the election. They need money to endure between elections and to be able to remain in the electoral race. Another response is that legislators regulate their funds if voters demand it. Yet, this other approach wrongly assumes that popularly supported reforms necessarily increase transparency and equity. In many Angel E. Alvarez cases, politicians manipulate scandal-driven reforms to avoid transparency and equity. An alternative answer is that funding regulations are shaped by political parties‘ specific needs for funding. Party organizations and electoral systems could certainly make some reforms more likely than others, but they are both endogenous to politicians‘ anticipations of electoral results.