A Collection of Italian Opera Libretti in the Syracuse University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacini, Parody and Il Pirata Alexander Weatherson

“Nell’orror di mie sciagure” Pacini, parody and Il pirata Alexander Weatherson Rivalry takes many often-disconcerting forms. In the closed and highly competitive world of the cartellone it could be bitter, occasionally desperate. Only in the hands of an inveterate tease could it be amusing. Or tragi-comic, which might in fact be a better description. That there was a huge gulf socially between Vincenzo Bellini and Giovanni Pacini is not in any doubt, the latter - in the wake of his highly publicised liaison with Pauline Bonaparte, sister of Napoleon - enjoyed the kind of notoriety that nowadays would earn him the constant attention of the media, he was a high-profile figure and positively reveled in this status. Musically too there was a gulf. On the stage since his sixteenth year he was also an exceptionally experienced composer who had enjoyed collaboration with, and the confidence of, Rossini. No further professional accolade would have been necessary during the early decades of the nineteenth century On 20 November 1826 - his account in his memoirs Le mie memorie artistiche1 is typically convoluted - Giovanni Pacini was escorted around the Conservatorio di S. Pietro a Majella of Naples by Niccolò Zingarelli the day after the resounding success of his Niobe, itself on the anniversary of the prima of his even more triumphant L’ultimo giorno di Pompei, both at the Real Teatro S.Carlo. In the Refettorio degli alunni he encountered Bellini for what seems to have been the first time2 among a crowd of other students who threw bottles and plates in the air in his honour.3 That the meeting between the concittadini did not go well, this enthusiasm notwithstanding, can be taken for granted. -

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini

LE MIE MEMORIE ARTISTICHE Giovanni Pacini Vertaling: Adriaan van der Tang 1 2 VOORWOORD De meeste operaliefhebbers nemen als vanzelfsprekend aan dat drie componisten in de eerste helft van de negentiende eeuw het muziekleven in Italië domineerden: Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini. Deze veronderstelling is enerzijds gebaseerd op het feit dat een flink aantal werken van hun hand tot op de huidige dag overal ter wereld wordt uitgevoerd, anderzijds op een ruime belangstelling van onder- zoekers, die geleid heeft tot talrijke wetenschappelijke publicaties die mede hun weg vonden naar een ruimer publiek. Ook de fonografische industrie heeft zich de laatste vijftig, zestig jaar voornamelijk geconcentreerd op de populaire opera’s van dit drietal, naast werken die in artistiek of muziek- historisch opzicht van belang werden geacht. Sinds een aantal jaren worden, vooral in kleinere Italiaanse theaters en zomerfestivals, in toenemende mate opera’s uitgevoerd van vergeten meesters, die bij nadere beschouwing in genoemd tijdperk wel degelijk een rol van betekenis hebben vervuld. Registraties van deze opvoeringen worden door de ware melomaan begroet als een welkome ont- dekking, evenals de studio-opnamen die wij te danken hebben aan de prijzenswaardige initiatieven van Opera Rara, waardoor men kennis kan nemen van de muziek van componisten als Mayr, Mercadante, Meyerbeer, Pacini, Paër en anderen. Een van deze vergeten componisten, Giovanni Pacini, speelt met betrekking tot onze algemene kennis van de negentiende-eeuwse operahistorie een bijzondere rol. Zijn autobiografie Le mie memorie artistiche uit 1865 is een belangrijke bron van informatie voor muziekwetenschappers - en andere geïnteresseerden - die zich toeleggen op het bestuderen van de ontwikkeling van de opera in de belcantoperiode. -

Le Opere Europee, 1750-1814

Le opere europee, 1750-1814 Michele Girardi (in fieri, 18 ottobre 2010) 1751 (1) data luogo titolo librettista compositore Artaserse, Pietro Metastasio Baldassarre opera in tre atti Galuppi 1754 (1) data luogo titolo librettista compositore 26.X Venezia, Teatro Il filosofo di campagna, Carlo Goldoni Baldassarre Grimani di S. dramma giocoso per Galuppi Samuele musica in tre atti 1757 (1) data luogo titolo librettista compositore autunno Venezia, Teatro L’isola disabitata, Carlo Goldoni Giuseppe Grimani di S. dramma giocoso per Scarlatti Samuele musica in tre atti 1760 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore 6.II Roma Teatro delle La Cecchina, ossia La Carlo Goldoni Nicola Piccinni Dame buona figliola, opera in tre atti OUIS NSEAUME IV Wien, Burgtheater L’ivrogne corrigée, da L A e Cristoph JEAN-BAPTISTE opéra-comique in due atti LOURDET DE SANTERRE, Willibald Gluck L’ivrogne corrigée, ou le mariage du diable 1761 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore 10.VI Bologna La buona figliola Carlo Goldoni Nicola Piccinni maritata, opera in tre atti Armida, opera da TASSO, Tommaso Gerusalemme Liberata Traetta 1765 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore 26.I London, King’s Adriano in Siria, dramma Pietro Metastasio Johann Christian Theater per musica in tre atti Bach 2.II London, Covent Artaxerxes, Arne ? Thomas Augustin Garden opera seria in tre atti (da METASTASIO) Arne Artaserse, Pietro Metastasio Giovanni dramma per musica in tre Paisiello atti 1766 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore Artaserse, Pietro Metastasio Nicola Piccinni opera in tre atti Venezia La buona figliola Bianchi Latilla supposta, opera 1767 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore 13.V Salzburg Apollo et Hyacinthus, Rufinus Widl Wolfgang seu Hyacinthi Amadeus Mozart metamorphosis, commedia in latino 26.XII Wien Alceste, opera in tre atti Ranieri Christoph de’Calzabigi Willibald Gluck (da EURIPIDE, Alceste) 1768 (2) data luogo titolo librettista compositore XI Wien, teatro-giardino Bastien und Bastienne, Friedrich W. -

La Colección De Música Del Infante Don Francisco De Paula Antonio De Borbón

COLECCIONES SINGULARES DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL 10 La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón COLECCIONES SINGULARES DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA, 10 La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón en la Biblioteca Nacional de España Elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez José María Soto de Lanuza Madrid, 2012 Director del Departamento de Música y Audiovisuales José Carlos Gosálvez Lara Jefa del Servicio de Partituras Carmen Velázquez Domínguez Elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez José María Soto de Lanuza Servicio de Partituras Ilustración p. 4: Ángel María Cortellini y Hernández, El infante Francisco de Paula, 1855. Madrid, Museo del Romanticismo, CE0523 NIPO: 552-10-018-X © Biblioteca Nacional de España. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte © De los textos introductorios: sus autores Catálogo general de publicaciones ofi ciales de la Administración General del Estado: http://publicacionesofi ciales.boe.es CATALOGACIÓN EN PUBLICACIÓN DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA Biblioteca Nacional de España La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón en la Biblioteca Nacional de España / elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez, José María Soto de Lanuza. – Madrid : Biblioteca Nacional de España, 2012 1 recurso en línea : PDF. — (Colecciones singulares de la Biblioteca Nacional ; 10) Bibliografía: p. 273-274. Índices Incluye transcripción y reproducción facsímil del inventario manuscrito M/1008 NIPO 552-10-018-X 1. Borbón, Francisco de Paula de, Infante de España–Biblioteca–Catálogos. 2. Partituras–Biblioteca Nacional de España– Catálogos. 3. Música–Manuscritos–Bibliografías. I. Lozano, Isabel (1960-). II. Soto de Lanuza, José María (1954- ). -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

El Camino De Verdi Al Verismo: La Gioconda De Ponchielli the Road of Verdi to Verism: La Gioconda De Ponchielli

Revista AV Notas, Nº8 ISSN: 2529-8577 Diciembre, 2019 EL CAMINO DE VERDI AL VERISMO: LA GIOCONDA DE PONCHIELLI THE ROAD OF VERDI TO VERISM: LA GIOCONDA DE PONCHIELLI Joaquín Piñeiro Blanca Universidad de Cádiz RESUMEN Con Giuseppe Verdi se amplificaron y superaron los límites del Bel Canto representado, fundamentalmente, por Rossini, Bellini y Donizetti. Se abrieron nuevos caminos para la lírica italiana y en la evolución que terminaría derivando en la eclosión del Verismo que se articuló en torno a una nutrida generación de autores como Leoncavallo, Mascagni o Puccini. Entre Verdi y la Giovane Scuola se situaron algunos compositores que constituyeron un puente entre ambos momentos creativos. Entre ellos destacó Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886), profesor de algunos de los músicos más destacados del Verismo y autor de una de las óperas más influyentes del momento: La Gioconda (1876-1880), estudiada en este artículo en sus singularidades formales y de contenido que, en varios aspectos, hacen que se adelante al modelo teórico verista. Por otra parte, se estudian también cuáles son los elementos que conserva de los compositores italianos precedentes y las influencias del modelo estético francés, lo que determina que la obra y su compositor sean de complicada clasificación, aunque habitualmente se le identifique incorrectamente con el Verismo. Palabras clave: Ponchielli; Verismo; Giovane Scuola; ópera; La Gioconda; Italia ABSTRACT With Giuseppe Verdi, the boundaries of Bel Canto were amplified and exceeded, mainly represented by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. New paths were opened for the Italian lyric and in the evolution that would end up leading to the emergence of Verismo that was articulated around a large generation of authors such as Leoncavallo, Mascagni or Puccini. -

Giacomo Puccini Krassimira Stoyanova

Giacomo Puccini Complete Songs for Soprano and Piano Krassimira Stoyanova Maria Prinz, Piano Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) 5 Ave Maria Leopolda (Giacomo Puccini) Conservatory. It is introduced by solemn organ harmonies (Milan, 20 May 1896) with strong treble line. The melody is shaped by slow Songs This short song is a setting of one of the composer’s letters lingering inflections of considerable emotional intensity. The Giacomo (Antonio Domenico Michele Seconda Maria) Gramophone Company (Italy) Ltd. The tone of this song, to the conductor Leopoldo Mugnone (who conducted hymn moves on to a more questioning phase, and concludes Puccini (1858-1924) was born into a family with long musical by the famous librettist Illica, a man of exuberant and violent Manon Lescaut and La Bohème in Palermo). It is a jocular with a smooth organ postlude. The tune was used by the traditions. He studied with the violinist Antonio Bazzini passions, celebrates the positivism of the late 19th century. salutation, offering greetings to his spouse Maria Leopolda, composer in his first opera Le Villi (1883) as the orchestral (1818-1897) and the opera composer Amilcare Ponchielli The text reflects that, although life is transient, we sense the from the dark Elvira (Bonturi, Puccini’s wife) and the blonde introduction to No. 5 and the following prayer Angiol di Dio. (1834-1886), and began his career writing church music. existence of an ideal that transcends it, conquering oblivion Foschinetta (Germignani, Puccini’s stepdaughter), who He is famous for his series of bold and impassioned operas and death. The musical setting is confident and aspirational, send kisses and flowers. -

Roger Parker: Curriculum Vitae

1 Roger Parker Publications I Books 1. Giacomo Puccini: La bohème (Cambridge, 1986). With Arthur Groos 2. Studies in Early Verdi (1832-1844) (New York, 1989) 3. Leonora’s Last Act: Essays in Verdian Discourse (Princeton, 1997) 4. “Arpa d’or”: The Verdian Patriotic Chorus (Parma, 1997) 5. Remaking the Song: Operatic Visions and Revisions from Handel to Berio (Berkeley, 2006) 6. New Grove Guide to Verdi and his Operas (Oxford, 2007); revised entries from The New Grove Dictionaries (see VIII/2 and VIII/5 below) 7. Opera’s Last Four Hundred Years (in preparation, to be published by Penguin Books/Norton). With Carolyn Abbate II Books (edited/translated) 1. Gabriele Baldini, The Story of Giuseppe Verdi (Cambridge, 1980); trans. and ed. 2. Reading Opera (Princeton, 1988); ed. with Arthur Groos 3. Analyzing Opera: Verdi and Wagner (Berkeley, 1989); ed. with Carolyn Abbate 4. Pierluigi Petrobelli, Music in the Theater: Essays on Verdi and Other Composers (Princeton, 1994); trans. 5. The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (Oxford, 1994); translated into German (Stuttgart. 1998), Italian (Milan, 1998), Spanish (Barcelona, 1998), Japanese (Tokyo, 1999); repr. (slightly revised) as The Oxford History of Opera (1996); repr. paperback (2001); ed. 6. Reading Critics Reading: Opera and Ballet Criticism in France from the Revolution to 1848 (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Mary Ann Smart 7. Verdi in Performance (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Alison Latham 8. Pensieri per un maestro: Studi in onore di Pierluigi Petrobelli (Turin, 2002); ed. with Stefano La Via 9. Puccini: Manon Lescaut, special issue of The Opera Quarterly, 24/1-2 (2008); ed. -

Download Five

Chapter Four “Un misérable eunuque” He had his Spring contract, his librettist was by his side and he had sympathy galore - no one whatsoever in musical circles in Milan could have been unaware of the Venetian scam,i from now on the guilty pair would be viewed askance by operatic managements throughout the peninsula. The direction of La Scala - only too willing to be supportive - agreed against all their usual caution to a religious heroine to fulfil Pacini’s contractual engagement and Giovanna d’Arco was the result - a saintly martyr bedevilled not just by the familiar occult and heretic foes but by the dilatory behaviour of the librettist in question - Gaetano Barbieri - who confessed that only half his text was actually in hand when rehearsals began in February 1830. Even if the great theatre was not unduly dismayed by the delay that resulted it put the opera and its composer into bad odour with its audience, after excuse after excuse and postponement after postponement of the prima, Pacini was obliged to ask the Chief of Police to impose a measure of calm and it was only at the very last gasp of the season that the curtains parted on his Giovanna and then before a sea of angry faces. The composer was hissed as he took his seat at the cembalo but smiled merely as they were confronted by a genuine novelty: Henriette Méric-Lalande in bed asleep. Her “dream aria” in which the bienheureuse greets her sacred destiny met with murmurs (Italian audiences seldom warmed to devotional intimacies on stage) but her truly seraphic cavatina, immaculately sung, brought them down to earth like a perfect miracle. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

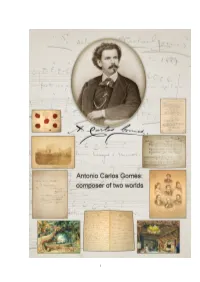

1 Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Antonio Carlos Gomes: composer of two worlds ID[ 2016-73] 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) Antonio Carlos Gomes: composer of two worlds gathers together documents that are accepted, not only by academic institutions, but also because they are mentioned in publications, newspapers, radio and TV programs, by a large part of the populace; this fact reinforces the symbolic value of the collective memory. However, documents produced by the composer, now submitted to the MOW have never before been presented as a homogeneous whole, capable of throwing light on the life and work on this – considered the composer of the Americas – of the greatest international prominence. Carlos Gomes had his works, notably in the operatic field, presented at the best known theatres of Europe and the Americas and with great success, starting with the world première of his third opera – Il Guarany – at the Teatro alla Scala – in Milan on March 18, 1870. From then onwards, he searched for originality in music which, until then, was still dependent and influenced by Italian opera. As a result he projected Brazil in the international music panorama and entered history as the most important non-European opera composer. This documentation then constitutes a source of inestimable value for the study of music of the second half of the XIX Century. 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) Arquivo Nacional (AN) - Ministério da Justiça - (Brasil) Escola de Música da Universidade Federal do Rio de -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today. -

"Casta Diva" from Bellini's

“Casta Diva” from Bellini's “Norma”--Rosa Ponselle; accompanied by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Giulio Setti (December 31, 1928 and January 30, 1929) Added to the National Registry: 2007 Essay by Judy Tsou (guest post)* Rosa Ponselle “Casta Diva” is the most famous aria of Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma” (1831). It is sung by the title character, a Druidess or priestess of the Gauls, in the first act. The opera takes place in Gaul between 100 and 50 BCE when the Romans were occupiers. The Gauls want Norma to declare war on the Romans, who have been oppressing them. Norma is hesitant to do so because she is secretly in love with Pollione, the Roman proconsul, and with whom she has borne two children. She assuages the people’s anger and convinces them that this is not the right time to revolt. She asserts that the Romans will eventually fall by their own doing, and the Gauls do not need to rise up now. It is at this point that Norma sings “Casta Diva,” a prayer to the moon goddess for peace, and eventually, conquering the Romans. When things between her and Pollione go sour, Norma tries to kill their children but ultimately cannot bring herself to do so. Eventually, she confesses her relationship with Pollione and sacrifices herself on the funeral pyre of her lover. “Norma” was the first of two operas commissioned in 1830 for which Bellini was paid an unprecedented 12,000 lire. “Norma” premiered on December 26, 1831 at La Scala, and the second opera, “Beatrice di Tenda,” premiered in 1833, but in Venice (La Fenice).