The English Anglican Practice of Pew-Renting, 1800-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Evelyn Underhill, “Church Congress Syllabus No. 3: the Christian Doctrine of Sin and Salvation, Part III: Worship”

ATR/100.3 Introduction to Evelyn Underhill, “Church Congress Syllabus No. 3: The Christian Doctrine of Sin and Salvation, Part III: Worship” Kathleen Henderson Staudt* This short piece by Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) appeared in a publication from the US Church Congress movement in the 1930s. It presents a remarkably concise summary of her major thought from this period.1 By this time, she was a well-known voice among Angli- cans. Indeed, Archbishop Michael Ramsey wrote that “in the twenties and thirties there were few, if indeed, any, in the Church of England who did more to help people to grasp the priority of prayer in the Christian life and the place of the contemplative element within it.”2 Underhill’s major work, Mysticism, continuously in print since its first publication in 1911, reflects at once Underhill’s broad scholarship on the mystics of the church, her engagement with such contemporaries as William James and Henri Bergson, and, perhaps most important, her curiosity and insight into the ways that the mystics’ experiences might inform the spiritual lives of ordinary people.3 The title of a later book, Practical Mysticism: A Little Book for Normal People (1914) summarizes what became most distinctive in Underhill’s voice: her ability to fuse the mystical tradition with the homely and the * Kathleen Henderson Staudt works as a teacher, poet, and spiritual director at Virginia Theological Seminary and Wesley Theological Seminary. Her poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in Weavings, Christianity and Literature, Sewanee Theo- logical Review, Ruminate, and Spiritus. She is an officer of the Evelyn Underhill As- sociation, and facilitates the annual day of quiet held in honor of Underhill in Wash- ington, DC each June. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire Wenham, Leslie P. How to cite: Wenham, Leslie P. (1946) A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HISTORY OP RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIREc i. To all those scholars, teachers, henefactors and governors who, by their loyalty, patiemce, generosity and care, have fostered the learning, promoted the welfare and built up the traditions of R. S. Y. this work is dedicated. iio A HISTORY OF RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIRE Leslie Po Wenham, M.A., MoLitt„ (late Scholar of University College, Durham) Ill, SCHOOL PRAYER. We give Thee most hiomble and hearty thanks, 0 most merciful Father, for our Founders, Governors and Benefactors, by whose benefit this school is brought up to Godliness and good learning: humbly beseeching Thee that we may answer the good intent of our Founders, "become profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth, and at last be partakers of the Glories of the Resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Tender Specs

7. Service Specification Route: 358 Contract Reference: QC48906 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Route Number 358 Terminus Points Orpington Station and Crystal Palace Parade On Mondays to Fridays, towards Orpington Station, buses are not required to serve Orpington, Walnuts Centre before 0830 (i.e. buses should not start arriving at Orpington, Walnuts Centre before 0830) Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 12th September 2015 Vehicle Type 70 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 12m long Current Maximum Approved 12.0 metres long and 2.5 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 - Route No. 119 minutes Extension Threshold - Route No. Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 0.95 119 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. -

Octobre 2013 Nouveautés – New Arrivals October 2013

Octobre 2013 Nouveautés – New Arrivals October 2013 ISBN: 9780521837491 (hbk.) ISBN: 9780521145916 (pbk.) ISBN: 0521145910 (pbk.) Auteur: Isidorus Hispalensis, sanctus, 560-636 Titre: The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville / Stephen A. Barney ... [et al.] ; with the collaboration of Muriel Hall. Éditeur: Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2010. Desc. matérielle: xii, 476 p. ; 24 cm. Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographical references and index. Langue: Translated from the Latin. AE 2 I833I75 2010 ISBN: 9789519264752 ISBN: 9519264752 Titre: Reappraisals of Eino Kaila's philosophy / edited by Ilkka Niiniluoto and Sami Pihlström. Éditeur: Helsinki : Philosophical Society of Finland, 2012. Desc. matérielle: 232 p. : ill. ; 25 cm. Collection: (Acta philosophica Fennica ; v. 89) Note bibliogr.: Includes bibliographies. Dépouil. complet: Eino Kaila in Carnap's circle / Juha Manninen -- From Carnap to Kaila : a neglected transition in the history of 'wissenschaftliche Philosophie' / Matthias Neuber -- Eino Kaila's critique of metaphysics / Ilkka Niiniluoto -- Eino Kaila's scientific philosophy / Anssi Korhonen -- Kaila and the problem of identification / Jaakko Hintikka -- Eino Kaila on the Aristotelian and Galilean traditions in science / Matti Sintonen -- Kaila's reception of Hume / Jani Hakkarainen -- Terminal causality, atomic dynamics and the tradition of formal theology / Michael Stöltzner -- Eino Kaila on pragmatism and religion / Sami Pihlström -- Eino Kaila on ethics / Mikko Salmela. B 20.6 F45 1935- 89 ISBN: 9789519264783 -

July 2005 No.178, Quarterly, Distributed Free to Members

NEWSLETTER Summer issue, July 2005 No.178, Quarterly, distributed free to members Registered with the Civic Trust and the London Forum of Amenity Societies, Registered Charity No.1058103 Website: www.brixtonsociety.org.uk Our next appearance: Sunday 25 September: Lambeth Country Show Ferndale Walk 16 & 17 July weekend Meet at 2-30 pm outside Clapham North Underground Station for a Once again we will be joining in with guided walk around Ferndale Ward, this big event in Brockwell Park, with led by Alan Piper. This will be a the Society’s stall in the usual area, circular route, based loosely on Brixton forming a block with kindred groups Heritage Trail No.2 but also including covering different parts of Lambeth. new or topical material. Do take the opportunity to check out our current publications, renew your membership and chat about your own interest in Brixton. Thursday 8 September: Revitalizing Brixton Caroline Townsend from Brixton Town Centre Office will update us on the Council’s big “Revitalize” package How well do you know your way around Ferndale which we first reported last October. Ward? The flats on the left recently replaced a Nearly a year on, how are the Brixton former prefab office at the corner of Hetherington parts of the plan shaping up? We hope and Kepler Roads, off Acre Lane. To the right is members will take the chance to one of the “pentagon blocks” of flats built by comment and ask questions. 7-30 pm Lambeth c.1968. Photo from James Toohill. at the Vida Walsh Centre, 2b Saltoun Road (facing Windrush Square) SW2. -

358 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

358 bus time schedule & line map 358 Crystal Palace View In Website Mode The 358 bus line (Crystal Palace) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Crystal Palace: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM (2) Orpington Station: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 358 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 358 bus arriving. Direction: Crystal Palace 358 bus Time Schedule 76 stops Crystal Palace Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Orpington Bus Station (E) Station Approach, London Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM High Storpington War Memorial (R) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM 299-301 High Street, London Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Orpington / Walnuts Centre (X) Friday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM High Storpington War Memorial (S) Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM 299-301 High Street, London Hillcrest Road Orpington (M) Sevenoaks Road, London 358 bus Info Sevenoaks Road / Tower Road (D) Direction: Crystal Palace Stops: 76 Sevenoaks Road Orpington Hospital Orpington Trip Duration: 77 min (E) Line Summary: Orpington Bus Station (E), High Helegan Close, London Storpington War Memorial (R), Orpington / Walnuts Centre (X), High Storpington War Memorial (S), Sevenoaks Road Cloonmore Avenue Orpington Hillcrest Road Orpington (M), Sevenoaks Road / (F) Tower Road (D), Sevenoaks Road Orpington Hospital Orpington (E), Sevenoaks Road Cloonmore Avenue Crescent Way (G) Orpington (F), Crescent Way (G), Glentrammon Road Green Street Green (E), Farnborough Hill Bus Garage Glentrammon -

Early Methodism in and Around Chester, 1749-1812

EARIvY METHODISM IN AND AROUND CHESTER — Among the many ancient cities in England which interest the traveller, and delight the antiquary, few, if any, can surpass Chester. Its walls, its bridges, its ruined priory, its many churches, its old houses, its almost unique " rows," all arrest and repay attention. The cathedral, though not one of the largest or most magnificent, recalls many names which deserve to be remembered The name of Matthew Henry sheds lustre on the city in which he spent fifteen years of his fruitful ministry ; and a monument has been most properly erected to his honour in one of the public thoroughfares, Methodists, too, equally with Churchmen and Dissenters, have reason to regard Chester with interest, and associate with it some of the most blessed names in their briefer history. ... By John Wesley made the head of a Circuit which reached from Warrington to Shrewsbury, it has the unique distinction of being the only Circuit which John Fletcher was ever appointed to superintend, with his curate and two other preachers to assist him. Probably no other Circuit in the Connexion has produced four preachers who have filled the chair of the Conference. But from Chester came Richard Reece, and John Gaulter, and the late Rev. John Bowers ; and a still greater orator than either, if not the most effective of all who have been raised up among us, Samuel Bradburn. (George Osborn, D.D. ; Mag., April, 1870.J Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/earlymethodisminOObretiala Rev. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

Columbian Congress of the Universalist Church for the World's

COLUMBIAN CONGRESS. Adopted. 1803. We believe that the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments contain a revelation of the character of God, and of the duty, interest and final destination of mankind. II. We believe that there is one God, whose nature is Love, revealed in one Lord fesus Christ, by one Holy Spirit of Grace, who will finally restore the whole family of mankind to holiness and happi- ness. III. We believe that holiness and true happiness are inseparably connected, and that believers ought to be careful to maintain order, and practice good works, for these things are good and profitable unto men. en < S — u O i THE Columbian Congress OF THE Tftniversalist Cburcb PAPERS AND ADDRESSES AT THE CONGRESS HELD AS A SECTION OF THE World's Congress auxiliary OF THE Columbian Exposition 1893 s> V G° z BOSTON AND CHICAGO sV^WASv ^ universalist publishing house ^S^i^-ij 1894 Copyright By Universalist Publishing House, A. D. 1893. PAPERS AND CONTRIBUTORS. PAGE. i. Universalism a System. i Rev. Stephen Crane, D. D.. Sycamore, 111. 2. Punishment Disciplinary. 14 Rev. Elmer H. Capen, D. D., President Tufts College. 3. Divine Omnipotence and Free Agency. 26 Rev. Charles E. Nash.'D. D., Brooklyn, N. Y. 4. Universal Holiness and Happiness. 51 Rev. J. Coleman Adams, D. D., Brooklyn. N. Y. 5. Harmony of the Divine Attributes. 67 Rev. Edgar Leavitt, Santa Cruz, Cal. 6. The Intrinsic Worth of Man. 88 Rev. Everett L. Rexford, D. D., Boston, Mass. 7. Universalism the Doctrine of the Bible. 100 Rev. -

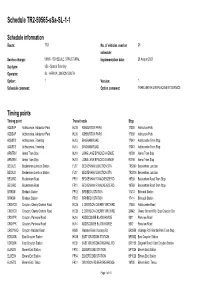

Standard Schedule TR2-58329-Ssa-SL-1-1

Schedule TR2-59565-sSa-SL-1-1 Schedule information Route: TR2 No. of vehicles used on 25 schedule: Service change: 59565 - SCHEDULE, STRUCTURAL Implementation date: 28 August 2021 Day type: sSa - Special Saturday Operator: SL - ARRIVA LONDON SOUTH Option: 1 Version: 1 Schedule comment: Option comment: TRAMLINK RAIL REPLACEMENT SERVICE Timing points Timing point Transit node Stop ADDSAP Addiscombe, Ashburton Park HJ08 ASHBURTON PARK 17338 Ashburton Park ADDSAP Addiscombe, Ashburton Park HJ08 ASHBURTON PARK 17339 Ashburton Park ADDSTS Addiscombe, Tramstop HJ15 BINGHAM ROAD 17342 Addiscombe Tram Stop ADDSTS Addiscombe, Tramstop HJ15 BINGHAM ROAD 17343 Addiscombe Tram Stop ARNTRM Arena Tram Stop HJ10 LONG LANE BYWOOD AVENUE 18799 Arena Tram Stop ARNTRM Arena Tram Stop HJ10 LONG LANE BYWOOD AVENUE R0746 Arena Tram Stop BECKJS Beckenham Junction Station FJ07 BECKENHAM JUNCTION STN TRS169 Beckenham Junction BECKJS Beckenham Junction Station FJ07 BECKENHAM JUNCTION STN TRS174 Beckenham Junction BECKRD Beckenham Road FP01 BECKENHAM R MACKENZIE RD 19768 Beckenham Road Tram Stop BECKRD Beckenham Road FP01 BECKENHAM R MACKENZIE RD 19769 Beckenham Road Tram Stop BIRKSN Birkbeck Station FP02 BIRKBECK STATION 17413 Birkbeck Station BIRKSN Birkbeck Station FP02 BIRKBECK STATION 17414 Birkbeck Station CROYCO Croydon, Cherry Orchard Road HC25 E CROYDON CHERRY ORCH RD 17348 Addiscombe Road CROYCO Croydon, Cherry Orchard Road HC25 E CROYDON CHERRY ORCH RD 26842 Cherry Orchard Rd / East Croydon Stn CROYPR Croydon, Parkview Road HJ14 ADDISCOMBE BLACK HORSE -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897.