First Tracking of Post-Breeding Migration of the Ruddy Kingfisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird List Column A: We Should Encounter (At Least a 90% Chance) Column B: May Encounter (About a 50%-90% Chance) Column C: Possible, but Unlikely (20% – 50% Chance)

THE PHILIPPINES Prospective Bird List Column A: we should encounter (at least a 90% chance) Column B: may encounter (about a 50%-90% chance) Column C: possible, but unlikely (20% – 50% chance) A B C Philippine Megapode (Tabon Scrubfowl) X Megapodius cumingii King Quail X Coturnix chinensis Red Junglefowl X Gallus gallus Palawan Peacock-Pheasant X Polyplectron emphanum Wandering Whistling Duck X Dendrocygna arcuata Eastern Spot-billed Duck X Anas zonorhyncha Philippine Duck X Anas luzonica Garganey X Anas querquedula Little Egret X Egretta garzetta Chinese Egret X Egretta eulophotes Eastern Reef Egret X Egretta sacra Grey Heron X Ardea cinerea Great-billed Heron X Ardea sumatrana Purple Heron X Ardea purpurea Great Egret X Ardea alba Intermediate Egret X Ardea intermedia Cattle Egret X Ardea ibis Javan Pond-Heron X Ardeola speciosa Striated Heron X Butorides striatus Yellow Bittern X Ixobrychus sinensis Von Schrenck's Bittern X Ixobrychus eurhythmus Cinnamon Bittern X Ixobrychus cinnamomeus Black Bittern X Ixobrychus flavicollis Black-crowned Night-Heron X Nycticorax nycticorax Western Osprey X Pandion haliaetus Oriental Honey-Buzzard X Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard X Pernis celebensis Black-winged Kite X Elanus caeruleus Brahminy Kite X Haliastur indus White-bellied Sea-Eagle X Haliaeetus leucogaster Grey-headed Fish-Eagle X Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com -

Ultimate Philippines

The bizarre-looking Philippine Frogmouth. Check those eyes! (Dani Lopez-Velasco). ULTIMATE PHILIPPINES 14 JANUARY – 4/10/17 FEBRUARY 2017 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO This year´s Birdquest “Ultimate Philippines” tour comprised of the main tour and two post-tour extensions, resulting in a five-week endemics bonanza. The first three weeks focused on the better-known islands of Luzon, Palawan and Mindanao, and here we had cracking views of some of those mind-blowing, world´s must-see birds, including Philippine Eagle, Palawan Peacock-Pheasant, Wattled Broadbill and Azure- breasted Pitta, amongst many other endemics. The first extension took us to the central Visayas where exciting endemics such as the stunning Yellow-faced Flameback, the endangered Negros Striped Babbler or the recently described Cebu Hawk-Owl were seen well, and we finished with a trip to Mindoro and remote Northern Luzon, where Scarlet-collared Flowerpecker and Whiskered Pitta delighted us. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Philippines www.birdquest-tours.com Our success rate with the endemics– the ones you come to the Philippines for- was overall very good, and highlights included no less than 14 species of owl recorded, including superb views of Luzon Scops Owl, 12 species of beautiful kingfishers, including Hombron´s (Blue-capped Wood) and Spotted Wood, 5 endemic racket-tails and 9 species of woodpeckers, including all 5 flamebacks. The once almost impossible Philippine Eagle-Owl showed brilliantly near Manila, odd looking Philippine and Palawan Frogmouths gave the best possible views, impressive Rufous and Writhed Hornbills (amongst 8 species of endemic hornbills) delighted us, and both Scale-feathered and Rough-crested (Red-c) Malkohas proved easy to see. -

A Bird's Eye View of Okinawa

A Bird’s Eye View of Okinawa by HIH Princess Takamado, Honorary President ne of the most beautiful of the many O“must visit” places in Japan is the Ryukyu Archipelago. These islands are an absolute treasure trove of cultural, scenic and environmental discoveries, and the local people are known for their warmth and welcoming nature. Ikebana International is delighted to be able to host the 2017 World Convention in Okinawa, and I look forward to welcoming those of you who will be joining us then. 13 Kagoshima Kagoshima pref. Those who are interested in flowers are generally interested in the environment. In many cultures, flowers and birds go together, and so, Osumi Islands Tanega too, in my case. As well as being the Honorary President of Ikebana International, I am also the Yaku Honorary President of BirdLife International, a worldwide conservation partnership based in Cambridge, UK, and representing approximately 120 countries or territories. In this article, I Tokara Islands would like introduce to you some of the birds of Okinawa Island as well as the other islands in the Ryukyu Archipelago and, in so doing, to give you Amami a sense of the rich ecosystem of the area. Amami Islands Kikaiga One Archipelago, Six Island Tokuno Groups The Ryukyu Archipelago is a chain of islands Okinawa pref. Okino Erabu that stretches southwest in an arc from Kyushu (Nansei-shoto) to Chinese Taiwan. Also called the Nansei Islands, the archipelago consists of over 100 islands. Administratively, the island groups of Kume Okinawa Naha Osumi, Tokara and Amami are part of Kagoshima Prefecture, whilst the island groups Ryukyu Archipelago of Okinawa, Sakishima (consisting of Miyako Okinawa Islands and Yaeyama Islands), Yonaguni and Daito are part of Okinawa Prefecture. -

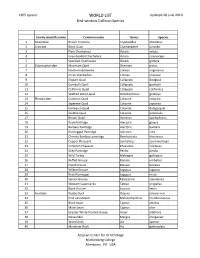

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Andamans Pocket Guide Print Taj Updated Low

This guide covers 139 birds found in the Andaman and Nicobar (A&N) Islands in WETLAND BIRDS the extreme south-east of India. Islands are unique ecosystems containing many endemic species of avifauna. The A&N islands too have several endemic birds, THICK-KNEE/ TURNSTONES some of which (eg. Narcondam Hornbill) are unique to specific islands. For ease are seen on sandy/ of reference, the species have been sorted into the following 5 categories: rocky beaches DUCKS WETLAND BIRDS WHIMBRELS, CURLEWS & feed on the surface of br Wetlands include ponds, streams, mangroves, marshes and coastal areas, which Birds of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands - a pocket guide to 139 familiar birds islands GOODWITS waterbodies Common Sandpiper Marsh Sandpiper Wood Sandpiper Beach Thick-knee Ruddy Turnstone are important habitats used by birds for feeding, nesting and breeding. Most of Little Egret Intermediate Egret Great Egret have very long beaks the birds in this group (eg. ducks, waders, herons etc) are only seen at wetlands 20 cm 23 cm 20 cm 55 cm 23 cm 63 cm 80 cm 90 cm whereas a few (Cattle Egret, White-throated Kingfisher, Pacific Golden Plover) Cotton Pygmy-Goose COOTS/MOORHENS Andaman Teal are frequently seen away from water as well. Several migratory species of 35 cm look like small ducks but 60 cm waders, ducks and terns visit our wetlands and coasts in winter. Birds of the Andaman lack webbed feet BIRDS OF PREY & Nicobar Islands br Birds of Prey or Raptors hunt and feed on other animals, including smaller birds. They have excellent eyesight, strong feet, sharp talons for hunting, and a hooked a pocket guide to 139 birds of the islands Terek Sandpiper Cattle Egret Pacific Reef Egret beak for tearing into flesh. -

Predlog Slovenskega Vrstnega Poimenovanja Vpijatov (Coraciiformes) Sveta

Predlog slovenskega vrstnega poimenovanja vpijatov (Coraciiformes) sveta Slovenian nomenclature of the Coraciiformes of the world – a proposal Al VREZEC 1, Petra VRH VREZEC 2, Janez GREGORI 3 Izvleček Prispevek podaja prvi celostni predlog slovenskih imen 178 vrst vpijatov (Coraciiformes) sveta s pregledom dosedanjega poimenovanja, in sicer za šest družin: zlatovranke (Coraciidae), ze mljovranke (Brachypteraciidae), motmoti (Momotidae), todiji (Todidae), vodomci (Alcedinidae) in legati (Meropidae). Predlog je bil pripravljen na naslednjih principih: (1) unikatnost imena, (2) imena so tvorjena po značilnostih vrste ali geografsko ter zgolj izjemoma po osebnih imenih, (3) sprejemljivo je poslovenjenje lokalnih imen, (4) uveljavljena in pogosteje uporabljena imena imajo prednost, če le niso v nasprotju s taksonomijo in imenikom ptic zahodne Palearktike, (5) oživlja nje starih slovenskih sinonimov domačih vrst pri poimenovanju neevropskih vrst, (6) imena naj bodo čim krajša (največ tri besede), enoimenska imena pa imajo prednost pred dvoimenskimi in ta pred troimenskimi, (7) rodovna imena niso nujno standardizirana za vse vrste istega rodu, (8) pridevnik »navadni« se praviloma opušča, (9) pri tvorbi novih rodovnih imen slediti imenotvorni logiki že imenovanih vrst v skupini glede na imenik zahodne Palearktike. Doslej je bilo v sloven ščini že imenovanih 35 % vrst vpijatov, 65 % pa jih v slovenščini tu imenujemo prvič. Ključne besede: slovenska imena, svet, zgodovina poimenovanja, ptičja imena, etimologija Abstract This paper presents the -

Praveen Review of Flycatcher 1609

Black-and-Orange Flycatcher J. Praveen & G. Kuriakose NOTE ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 21(12): 2517-2518 REFERENCES BIRDS OF CHIDIYATAPU BIOLOGICAL Ali, S. and S.D. Ripley (2001). Handbook of Birds of India and PARK, SOUTH ANDAMAN Pakistan Together With Those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Ceylon. Vol. 8. Oxford University Press, Delhi, 236pp. 1 2 BirdLife Fact Sheet (2006). http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/ Natarajan Ezhilarasi and Lalitha Vijayan index.html. Accessed on 28.vii.2006 Grimmett, R., C. Inskipp and T. Inskipp (1999). A Pocket Guide to 1, 2 Division of Conservation Ecology, Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. 1st edn. Oxford University Press, and Natural History (SACON), Anaikatty (P.O), Coimbatore, Delhi, 384pp. Tamil Nadu 641108, India Islam, M.Z and A.R. Rahmani (2004). Important Bird Areas in India: Email: 1 [email protected] Priority Sites for Conservation. Indian Bird Conservation Network: Bombay Natural History Society and BirdLife International (UK). Pp.xviii+1133. The Andaman and Nicobar (6045'-13041N & 92012'-93057'E) is a Kazmierczak, K. (2000). A Field Guide to Birds of the Indian major group of islands with a total coastal line of about 1962km. st Subcontinent. 1 edn. Pica Press, London, 352pp. The entire islands group cover 8,249 km², and Andaman group Kadur, S. (2006). Trip report - Anshi, Ganesh Gudi and Dandeli, BngBirds Yahoo Groups http://groups.yahoo.com/group/bngbirds/message/9626. has more than 325 islands (21 inhabited) which covers 6,408km² Accessed on 28.vii.2006 and Nicobar group with over 24 islands (13 inhabited) has an Mohan, R.V. -

Nesting Behaviour of the South Philippine Dwarf Kingfisher Ceyx Mindanensis 21

FORKTAIL 34 (2018): 19–21 Nesting behaviour of the South Philippine Dwarf Kingfisher Ceyx mindanensis MIGUEL DAVID DE LEON, NEIL KONRAD BINAYAO III, ROBERT HUTCHINSON, LEOMAR JOSE DOCTOLERO & DESMOND ALLEN South Philippine Dwarf Kingfisher Ceyx mindanensis is a poorly known, small forest kingfisher, endemic to the Philippine islands of Mindanao and Basilan. We describe here observations of the sites, habitats and structure of five nests of this species and accompanying feeding behaviour. Nests were holes excavated in a bank or in arboreal termitaria. Food brought to the nest was largely earthworms and small lizards, but also other invertebrates. INTRODUCTION Misamis Oriental province, on the coast of north-central Mindanao. All the nests were located within 10–150 m of human habitations The South Philippine Dwarf Kingfisher Ceyx mindanensis is a small and close to gullies that drained the forest floor. forest kingfisher, endemic to the islands of Mindanao and Basilan. Mapawa Nature Park: two nests were found at Mapawa It is a poorly known species, reported to be dependent on lowland Nature Park, about 2,500 ha of very open secondary forest at forest and as such is classified as Vulnerable (BirdLife International 400–500 m (8.45°N 124.70°E), located a few km south-east of 2017). Until recently it was considered conspecific with its close the city. The first nest, discovered in June 2015, was located in an relative in the northern Philippines, C. melanurus (including active arboreal termitarium. It was 2 m above ground level, on a the form samarensis), but was split by del Hoyo & Collar (2014). -

Email Communiqué

December, 2010, Contents email Communiqué A Joyful Christmas to our Readers Society of King Charles the Martyr In future issues American Region Isaac D’Israeli on the Royal Martyrdom The Practice of Joy: In the Stuart Court and the U.S. ‘Halcyonian Issue • December, 2010 Queen Victoria and the State Services More on Milton Attitudes toward Saint Charles and the Society Placing 30 January on Church Kalendars EDITOR, MARK A. WUONOLA, PH.D. • [email protected] ISSN 2153-6120 BACK ISSUES OF SKCM NEWS AND THE EMAIL COMMUNIQUÉ ARE POSTED AT THE AMERICAN REGION’S WEBSITE, WWW.SKCM-USA.ORG Usually, ‘Halcyon Days’, times of prosperity and affluence are fond reminiscences.. We hope that their characteristics will prevail in your life making your New Year serene. The Halcyon Days are reckoned as a spell of fourteen days falling around the Winter Solstice. The name and accompanying lore originated in ancient Greece, αλκυνως (Gr.) and alcedo (L.). meaning kingfisher, a non-passerine bird prevalent near water (especially the [Grecian] archipelago, and those of SE Asia), often crested, and taxonomically diverse, being of some twenty genera and 150 species. Some are piscivorous and others insectivorous. One Australian variety, on account of its loud morning call is called the ‘laughing jackass’ or, more respectably, ‘kookaburra bird’. According to Greek fable, the bird nests around the Winter Solstice and calms the waves, requiring calm waters for conception and during incubation. Whether the kingfisher’s reputedly floating nest Halcyon smyrnensis benefits from seasonally tranquil waters, or the bird, as reputed, calms the waters is of no moment here. -

RCP Have Been Created, Except Two 'Phase In'

CORACIIFORMES TAG REGIONAL COLLECTION PLAN Third Edition, December 31, 2008 White-throated Bee-eaters D. Shapiro, copyright Wildlife Conservation Society Prepared by the Coraciiformes Taxon Advisory Group Edited by Christine Sheppard TAG website address: http://www.coraciiformestag.com/ Table of Contents Page Coraciiformes TAG steering committee 3 TAG Advisors 4 Coraciiformes TAG definition and taxonomy 7 Species in the order Coraciiformes 8 Coraciiformes TAG Mission Statement and goals 13 Space issues 14 North American and Global ISIS population data for species in the Coraciiformes 15 Criteria Used in Evaluation of Taxa 20 Program definitions 21 Decision Tree 22 Decision tree diagrammed 24 Program designation assessment details for Coraciiformes taxa 25 Coraciiformes TAG programs and program status 27 Coraciiformes TAG programs, program functions and PMC advisors 28 Program narratives 29 References 36 CORACIIFORMES TAG STEERING COMMITTEE The Coraciiformes TAG has nine members, elected for staggered three year terms (excepting the chair). Chair: Christine Sheppard Curator, Ornithology, Wildlife Conservation Society/Bronx Zoo 2300 Southern Blvd. Bronx, NY 10460 Phone: 718 220-6882 Fax 718 733 7300 email: [email protected] Vice Chair: Lee Schoen, studbookkeeper Great and Rhino Hornbills Curator of Birds Audubon Zoo PO Box 4327 New Orleans, LA 70118 Phone: 504 861 5124 Fax: 504 866 0819 email: [email protected] Secretary: (non-voting) Kevin Graham , PMP coordinator, Blue-crowned Motmot Department of Ornithology Disney's Animal Kingdom PO Box 10000 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 Phone: (407) 938-2501 Fax: 407 939 6240 email: [email protected] John Azua Curator, Ornithology, Denver Zoological Gardens 2300 Steele St. -

Sulawesi & Moluccas Extension: August-September 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report Sulawesi & Moluccas Extension: August-September 2015 A Tropical Birding set departure tour Sulawesi (Indonesia): & The Moluccas Extension (Halmahera) Birding the Edge of “Wallace’s Line” Minahassa Masked-Owl Tangkoko This tour was incredible for nightbirds; 9 owls, 5 nightjars, and 1 owlet-nightjar all seen. This bird was entirely unexpected; rarely seen at night; we were very fortunate to see in the daytime. Voted as one of the top five birds of the tour. 15th August – 4th September 2015 Tour Leaders: Sam Woods & Theo Henoch “At the same time, the character of its natural history proves it to be a rather ancient land, since it possesses a number of animals peculiar to itself or common to small islands around it, but almost always distinct from those of New Guinea on the east, of Ceram (now Seram) on the south, and of Celebes (now Sulawesi) and the Sula islands on the west.” 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Sulawesi & Moluccas Extension: August-September 2015 British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, writing on Golilo (now called Halmahera), in the “Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan, and the Bird of Paradise. A Narrative of Travel, with studies of Man and Nature.” in 1869 Acclaimed British naturalist (and co-conspirator with Charles Darwin on the development of the theory of evolution of species by natural selection), Alfred Russel Wallace spoke of the “peculiar”, and it was indeed the peculiar, or ENDEMIC, which was the undoubted focus of this tour. -

First Report of the Palau Bird Records Committee

FIRST REPORT OF THE PALAU BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE DEMEI OTOBED, ALAN R. OLSEN†, and MILANG EBERDONG, Belau National Museum, P.O. Box 666, Koror, Palau 96940 HEATHER KETEBENGANG, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940; [email protected] MANDY T. ETPISON, Etpison Museum, P.O. Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940 H. DOUGLAS PRATT, 1205 Selwyn Lane, Cary, North Carolina 27511 GLENN H. MCKINLAY, C/55 Albert Road, Devonport, Auckland 0624, New Zealand GARY J. WILES, 521 Rogers St. SW, Olympia, Washington 98502 ERIC A. VANDERWERF, Pacific Rim Conservation, P.O. Box 61827, Honolulu, Hawaii 96839 MARK O’BRIEN, BirdLife International Pacific Regional Office, 10 MacGregor Road, Suva, Fiji RON LEIDICH, Planet Blue Kayak Tours, P.O. Box 7076, Koror, Palau 96940 UMAI BASILIUS and YALAP YALAP, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940 ABSTRACT: After compiling a historical list of 158 species of birds known to occur in Palau, the Palau Bird Records Committee accepted 10 first records of new occur- rences of bird species: the Common Pochard (Aythya ferina), Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor), Chinese Pond Heron (Ardeola bacchus), White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus), Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata), Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica), Channel-billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae), Ruddy Kingfisher (Halcyon coromanda), Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), and Isabelline Wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina). These additions bring Palau’s total list of accepted species to 168. We report Palau’s second records of the Broad-billed Sandpiper (Calidris falcinellus), Chestnut-winged Cuckoo (Clamator coromandus), Channel- billed Cuckoo, White-throated Needletail (Hirundapus caudacutus) and Oriental Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus orientalis).