The Effectiveness and Influence of the Select Committee System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDENT LIAISON COMMITTEE Terms of Reference

STUDENT LIAISON COMMITTEE Terms of Reference 1 Constitution and purpose 1.1 The University recognises that, in the interests of staff and students, it is important to continually advance the excellence of the student experience and the teaching, learning and research environment it provides. The voice of the student community is represented by the Students’ Union. 1.2 To this end and, in accordance with the provisions of the Articles of Government (paragraph 5.4), the University’s Governing Body has established a Student Liaison Committee (SLC). 1.3 The SLC provides a forum for students to raise views with the Board of Governors and members of the Academic Board and to: • consider and inform (the Board of Governors) on matters of concern and to advise the student body (Articles of Government paragraph 5.4); • receive reports on student satisfaction and the student experience and report to the Board of Governors; • provide communication channels between the student community and Governors; 2 Remit 2.1 To advise the University’s governing body on its statutory obligations with regard to the Students’ Union (SU), particularly the requirements of the Education Act 1994, and specifically: a) all matters concerning the SU’s Constitution which the SLC should review every five years (last reviewed 2011); b) all matters concerning the UWL/SU Code of Practice which the SLC should review every five years (last reviewed 2011); c) receive reports on the election of Officer Trustees in accordance with requirements of the Education Act 1994 (it has been agreed that these reports will only be brought forward if a substantial item needs to be brought to the Board’s attention). -

Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons

Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty July 2014 Cm 8914 Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14 Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty July 2014 Cm 8914 © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/ or email [email protected] Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. Print ISBN 9781474109796 Web ISBN 9781474109802 Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ID P002659226 42260 07/14 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Government Response to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee 24th Report HC 109-1 of Session 2013-14, Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons The Government welcomes the European Scrutiny Committee’s Inquiry into Reforming the Scrutiny System in the House of Commons and the detailed consideration the Committee has given this important issue. -

Hitachi Brings Rail Manufacturing Back to Its British Birthplace

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Hitachi brings rail manufacturing back to its British birthplace Newton Aycliffe, County Durham; 3rd September, 2015 – Hitachi Rail today celebrated the return of rail manufacturing to its British home in the North East, joining with key delivery partners at the official opening of a £82 million Rail Vehicle Manufacturing Facility in Newton Aycliffe, County Durham. The facility is where the Government’s new InterCity Express (IEP) trains for the East Coast Main Line and Great Western Main Line, and AT200 commuter trains for Scotland, will be manufactured. Hitachi, Ltd. Chairman & CEO, Hiroaki Nakanishi, welcomed the Secretary of State for Transport Patrick McLoughlin MP and Rail Minister Claire Perry MP, along with over 500 invited guests, to the opening ceremony and for guided tours of the state-of-the-art rail vehicle manufacturing facility. Invited guests also witnessed the unveiling of the first fully fitted-out IEP train to arrive in the UK. Welcoming the opening, Prime Minister David Cameron said: "This massive investment from Hitachi shows confidence in the strength of Britain’s growing economy. This new train facility will not only provide good jobs for working people but will build the next generation of intercity trains, improving travel for commuters and families, as well as strengthening the infrastructure we need to help the UK grow.” Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said: "Today we see a major boost for the UK with Hitachi investing millions in returning train manufacturing to the North East. This state of the art facility will grow and secure jobs for decades to come and will help us to build the Northern Powerhouse, while at the same time revitalising one of our oldest industries in the region within which this - more - - 2 - tradition is synonymous.” Chairman & CEO of Hitachi, Ltd., Hiroaki Nakanishi, said: "Today is a momentous occasion for Hitachi Rail, Newton Aycliffe and the British rail industry. -

Hansard Society Evidence to the House of Lords Liaison Committee: Review of Investigative and Scrutiny Committees

Hansard Society evidence to the House of Lords Liaison Committee: Review of investigative and scrutiny committees Submitted: May 2018 Authors: Dr Ruth Fox (Director) and Dr Brigid Fowler (Senior Researcher) 2 Summary This submission covers: • Strengths and weaknesses of the current House of Lords committee structure • Possible changes to the current structure, focusing on: the quality of the legislative process; devolution; and policy foresight/horizon-scanning • Brexit-related considerations • Trade policy • Public engagement We recommend: • On the quality of the legislative process: the creation of a Legislative Standards Committee and a Post-Legislative Scrutiny Committee, and that the remit of the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee be amended • On devolution, the creation of a new permanent committee • On policy foresight/horizon-scanning, the creation of a new ‘Future Forum’ or Committee • On Brexit-related matters, that the European Union Committee will need to continue to operate during any post-Brexit transition period as provided for in the draft UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement • On trade policy, that the Lords committee structure will need to change to accommodate scrutiny of this new policy area, and that the House will need to develop a view, ideally sooner rather than later, on how this might best be effected, in cooperation with the Commons. Submission Strengths and weaknesses of the current House of Lords committee structure 1. The House of Lords committee structure has a number of important strengths that should be retained in any reformed system: • It is more flexible than the Commons’ system: the fact that the committee structure is not tied to the shadowing of government departments allows the Upper House more discretion. -

Report of the Select Committee on the Reduction of Standing Committees of Tynwald

REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REDUCTION OF STANDING COMMITTEES OF TYNWALD t i I. • REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REDUCTION OF STANDING COMMITTEES OF TYNWALD To the Honourable Noel Q Cringle, President of Tynwald, and the Honourable Members of the Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Background At the sitting of Tynwald Court on 21st May 2002 it was resolved that a Select Committee of five members be established to - "investigate and report by no later than July 2003 on the feasibility of reducing the number of Standing Committees of Tynwald along with any recommendations as to the responsibilities and membership and any proposals for change." 2. Mr Karran, Mr Lowey, Mr Quayle, Mr Quine and Mr Speaker were elected. At 4, the first meeting Mr Speaker was unanimously elected as Chairman. 3. The Committee has held four meetings. C/RSC/02/plb PART 2 STRATEGY 2.1 The Committees of Tynwald that would be examined were determined as: Committee on Constitutional Matters; Committee on the Declaration of Members' Interests, Ecclesiastical Committee; Committee on Economic Initiatives; Joint Committee on the Emoluments of Certain Public Servants; Committee on Expenditure and Public Accounts; Tynwald Ceremony Arrangements Committee; Tynwald Honours Committee; Tynwald Management Committee; Tynwald Members' Pension Scheme Management Committee; and Tynwald Standing Orders Committee of Tynwald. A brief summary of the membership and terms of reference of each standing committee is attached as Appendix 1. 2 C/RSC/02/plb 2.2 In order to facilitate its investigation your Committee also decided that - (a) Comparative information on committee structures in adjacent parliaments should be obtained. -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-07-09 18:01 1 Wimbledon: Serena Williams eyes revenge against Angelique Kerber in today's final (1.14/2) Serena Williams has history in her sights as the defending champion plots to avenge one of the most painful defeats of her career by beating Angelique Kerber in today’s Wimbledon final 2016-07-09 14:37 1KB www.mid-day.com 2 Phoenix police use tear gas on Black Lives Matter rally (PHOTOS, VIDEOS) — RT America (1.03/2) Police have used pepper spray during a civil rights rally in Phoenix, Arizona, late on Friday night. The use of impact munitions didn’t lead to any injuries, and no arrests have been made, Phoenix Police Chief said. 2016-07-09 18:00 1KB www.rt.com 3 Castile would be alive today if he were white: Minnesota Governor (1.02/2) A county prosecutor investigating the police shooting of a black motorist in Minnesota on Friday said law enforcement authorities in his state and nationwide must improve practices and procedures to prevent future such tragedies, regardless of the outcome of his probe. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 4 Thousands take to streets across US to protest police violence (1.02/2) Thousands of people took to the streets in US cities on Friday to denounce the fatal police shootings of two black men this week, marching the day after a gunman killed five police officers watching over a similar demonstration in Dallas. 2016-07-09 18:00 3KB www.timeslive.co.za 5 Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program (1.02/2) TEHRAN, Iran—Iran says it will continue its ballistic missile program after claims made by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon that its missile tests aren't in the spirit of the 2016-07-09 17:37 1KB newsinfo.inquirer.net 6 Hillary Clinton reacts to Dallas shootings In an interview with Scott Pelley that aired first on CBSN, Hillary (1.02/2) Clinton shared her thoughts on Thursday's shooting in Dallas. -

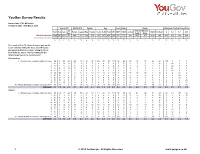

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1703 GB Adults Fieldwork: 25th - 26th March 2019 Vote in 2017 EU Ref 2016 Gender Age Social Grade Region Likelihood of voting Conservative Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Remain Leave Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland 0 1-4 5-7 8-10 Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 1703 562 526 95 656 702 824 879 187 717 405 393 971 732 204 569 368 416 146 640 303 342 419 Unweighted Sample 1703 619 526 110 737 720 766 937 148 684 447 424 1012 691 174 615 373 399 142 622 294 327 460 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 means you would never consider voting for them, and 10 means you would definitely consider voting for them, how likely are you to consider voting for the following parties at the next election? Conservative 0 - Would never consider voting for them 38 8 58 40 45 26 38 37 45 40 39 27 36 40 35 33 37 44 42 100 0 0 0 1 6 2 9 12 7 4 7 5 3 8 5 3 5 7 4 7 4 6 9 0 32 0 0 2 5 1 6 11 6 3 5 5 7 5 5 4 5 6 7 4 5 5 6 0 28 0 0 3 4 2 6 10 5 3 4 3 7 4 3 3 4 3 5 4 3 4 4 0 21 0 0 4 3 2 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 4 3 2 3 3 3 3 5 2 3 0 19 0 0 5 10 10 8 6 8 11 8 13 10 11 9 10 9 12 15 10 10 8 13 0 0 52 0 6 4 4 5 5 3 7 5 4 7 5 4 3 5 4 6 4 5 4 3 0 0 22 0 7 5 11 2 4 5 7 6 5 3 5 6 6 5 5 5 5 6 6 2 0 0 26 0 8 5 10 1 4 4 8 5 5 1 5 7 5 6 4 3 6 4 5 5 0 0 0 20 9 3 7 0 3 2 4 3 3 3 2 3 5 4 2 4 4 2 2 3 0 0 0 12 10 - Would definitely consider voting for them 17 44 2 4 12 26 16 18 7 11 16 33 19 14 11 21 17 15 11 0 0 0 68 AVERAGE 3.9 7.5 1.6 2.6 3.1 5.4 3.8 4.1 2.8 3.3 3.9 5.5 4.2 3.5 -

May Axes Cameron Allies in Ruthless Cabinet Cull

Max 22C min 7C Friday July 15 2016 | thetimes.co.uk | No 71963 Only 80p to subscribers £1.40 BRICKS The best places to Britain’s top 25 &MORTAR PROPERTY small museums PULLOUT find a holiday home Times2 Junk foodban May axes Cameron allies dropped after ministers bow in ruthless cabinet cull to lobbyists Gove, Morgan and Letwin sacked as state-educated ministers dominate top team Chris Smyth Health Editor DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES The fight against child obesity has been Francis Elliott Political Editor half a century. The one Old Etonian, left in the hands of food companies in a Sam Coates, Lucy Fisher Boris Johnson, endureda difficult debut watering down of ministers’ promises as foreign secretary when he was booed after lobbying by the industry. Theresa May scythed through David during his first engagement, a Bastille Manufacturers will not be forced to Cameron’s allies in a bloody cull that Day reception at the French embassy. make products healthier and no con- consigned nine members of his former Mr Johnson, Brexit’s most powerful crete measures to curb marketing of cabinet to the back benches yesterday. advocate, was brandeda liar and a “bor- unhealthyproductshave beenincluded In a purge more brutal than Harold derline racist” by EU ministers and dip- in a long-delayed blueprint on tackling Macmillan’s “night of the long knives” lomats. France’s foreign minister, Jean- obesity. in 1962, Michael Gove, the justice sec- Marc Ayrault, said that Mr Johnson A ban on junk food at shop checkouts retary; Nicky Morgan, the education had told “lies” during the EU referen- has been dropped and an end to adver- secretary; John Whittingdale, the cul- dum campaign while Frank-Walter tisements for unhealthy food before the ture secretary; and Oliver Letwin, the Steinmeier, his German counterpart, 9pm watershed has not been included cabinet office minister, joined George called the former mayor of London’s in leaked drafts seen by The Times. -

Triangle of Partnership Or Conflicts

International Journal of Political Science (IJPS) Volume 4, Issue 4, 2018, PP 34-41 ISSN 2454-9452 http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9452.0404006 www.arcjournals.org Turkey in Relation to EU and Russia - Triangle of Partnership or Conflicts Bulent Acma1*, Mehmet Ali Ozcobanlar2 1Anadolu University, Department of Economics, Eskisehir/Turkey. 2Department of Management, University of Warsaw, Warsaw/Poland *Corresponding Author: Bulent Acma, Anadolu University, Department of Economics, Turkey Abstract: EU-Turkey-Russia. In this research, the relationship between European Union and Turkey, an age long neighbour to the continent and an associate member of European Union since 1963, are examined and analysed. Turkey is an important ally of the union and the only Muslim country-member of NATO from the very beginning of the treaty, since it joined the organization in 1952, at the same year that Greece did. The relations between the Union and Turkey are examined from the aspect of security. The reactions of the European Union to the recent political changes in Republic of Turkey, after the 15 July 2016 failed coup- attempt, are also examined. The EU - Turkey relations after the failed coup attempt and the international impact of it are studied from the perspective of political and social influence it might have. Russia is a vital energy supplier to the Union and Turkey is a geopolitical bridge between west and east, an energy corridor standing at the crossroad of important energy markets such as Iran, Iraq and Azerbaijan. The country has also relations with Cyprus, an upcoming gas supplier and an EU member. -

Programme for Committee Clerks of the Parliament of Guyana

0 1021CBP/GUYANA15 CPA UK & Parliament of Guyana Capacity Building Programme Activity 1: Programme for Committee Clerks of the Parliament of Guyana 16-19 November 2015, Houses of Parliament, London Report 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2. AIM & OBJECTIVES 3 3. FACILITATORS AND DELEGATION 3 4. PROGRAMME DETAILS 4 5. PROGRAMME COMMENTS 7 WIDENING THE SCOPE AND IMPACT OF COMMITTEE INQUIRIES 7 LIAISON COMMITTEE 8 THE RESPECT POLICY 8 PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND OUTREACH 9 SECURITY SENSITIVE COMMITTEES 9 MINUTES, BRIEFS AND REPORTS 10 RESEARCH 11 6. PROGRAMME BUDGET 12 7. OUTCOMES AND FOLLOW-UP ACTIVITIES 12 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 13 9. ABOUT CPA UK 13 ANNEX A. PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES 14 B. SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES 16 1 2 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.01 In October 2015, CPA UK and the Parliament of Guyana embarked on a seven-month Capacity Building Programme jointly funded by CPA UK and the British High Commission, Georgetown. The aims of the wider programme are to: • Enhance the Assembly’s ability to conduct its business effectively • Work with the Assembly’s parliamentary committees to enhance their oversight capacity • Work with the Parliamentary Leadership, to strengthen its administrative, financial, and procedural independence • Work with parliamentary officials to support the functioning of the Assembly • Address the challenges of maintaining a successful coalition government • Support the interaction between UK, Guyanese and Caribbean Parliamentarians to discuss issues of regional interest; sustainability, energy and development 1.2 The first agreed activity of the Capacity Building Programme was a Workshop for Committee Clerks of the Parliament of Guyana based in Westminster. 1.3 The Programme involved two Committee Clerks and four Assistant Committee Clerks. -

The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union

THE FUTURE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Cm 9593 THE FUTURE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE EUROPEAN UNION Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty July 2018 Cm 9593 © Crown copyright 2018 Any enquiries regarding this publication This publication is licensed under the terms should be sent to us at of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except [email protected] where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- ISBN 978-1-5286-0701-8 government-licence/version/3 CCS0718050590-001 07/18 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain Printed on paper containing 75% recycled permission from the copyright holders fibre content minimum. concerned. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on This publication is available at behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s www.gov.uk/government/publications Stationery Office The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union 1 Foreword by the Prime Minister In the referendum on 23 June 2016 – the largest ever democratic exercise in the United Kingdom – the British people voted to leave the European Union. And that is what we will do – leaving the Single Market and the Customs Union, ending free movement and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in this country, leaving the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common Fisheries Policy, and ending the days of sending vast sums of money to the EU every year. We will take back control of our money, laws, and borders, and begin a new exciting chapter in our nation’s history.