Status of Killer Whales in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gary's Charts

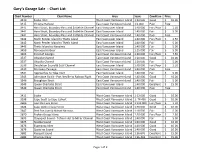

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

Burrard Inlet Underwater Noise Study

Vancouver Fraser Port Authorit Burrard Inlet underwater noise study: 2020 final report ECHO Program study summary This study was undertaken for the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority-led Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program and project partner Tsleil-Waututh Nation with financial support from Transport Canada to learn more about underwater noise and cetacean presence in Burrard Inlet. Building upon the 2019 monitoring project in Burrard Inlet, this project set out to monitor underwater noise and the presence of cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoise) in Burrard Inlet, a marine mammal habitat and a key waterway for commercial shipping, port-related activities, and passenger transportation. This document summarizes the project question and describes the methods, key findings, and conclusions. What questions was the study trying to answer? The second year of the Burrard Inlet underwater noise study sought to evaluate longer-term trends in total ambient noise and marine mammal presence, while building upon the results from 2019. Who conducted the project? SMRU Consulting North America (SMRU) was awarded the contract for the 2019 monitoring program, and was retained by Vancouver Fraser Port Authority to continue monitoring though 2020 at fewer sampling locations. What methods were used? Bottom-mounted SoundTrap hydrophone recorders were deployed in two locations in the inner and outer harbour: one at Burrard Inlet East near the Tsleil-Waututh Nation reserve lands and Burnaby petroleum terminals, and one in English Bay between anchorages 1 and 3. Acoustic data were collected over approximately one year between February 2020 and February 2021. The figure below shows the approximate locations of the hydrophone deployments. -

Killer Controversy, Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity

Killer Controversy Why orcas should no longer be kept in captivity ©Naomi Rose - HSI Prepared by Naomi A. Rose, Ph.D. Senior Scientist September 2011 The citation for this report should be as follows: Rose, N. A. 2011. Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity. Humane Society International and The Humane Society of the United States, Washington, D.C. 16 pp. © 2011 Humane Society International and The Humane Society of the United States. All rights reserved. i Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Introduction 1 The Evidence 1 Longevity/survival rates/mortality 1 Age distribution 4 Causes of death 5 Dental health 5 Aberrant behavior 7 Human injuries and deaths 8 Conclusion 8 Ending the public display of orcas 9 What next? 10 Acknowledgments 11 ii iii Killer Controversy Why orcas should no longer be kept in captivity Introduction Since 1964, when a killer whale or orca (Orcinus orca) was first put on public display1, the image of this black-and-white marine icon has been rehabilitated from fearsome killer to cuddly sea panda. Once shot at by fishermen as a dangerous pest, the orca is now the star performer in theme park shows. But both these images are one-dimensional, a disservice to a species that may be second only to human beings when it comes to behavioral, linguistic, and ecological diversity and complexity. Orcas are intelligent and family-oriented. They are long-lived and self- aware. They are socially complex, with cultural traditions. They are the largest animal, and by far the largest predator, held in captivity. -

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes**

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes** Canada has just passed a law making it illegal to keep cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in captivity for display and entertainment: the Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act (Bill S-203). Only two facilities in the country still possess captive cetaceans: Marineland in Niagara Falls, Ontario; and the Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, British Columbia. The Vancouver Aquarium has announced that it will voluntarily end its cetacean program. This article summarizes the provisions of Bill S-203 and recounts its eventful journey through the legislative process. It gives an overview of the history of cetacean captivity in Canada, and of relevant existing 2019 CanLIIDocs 2114 Canadian law that regulates the capture and keeping of cetaceans. The article argues that social norms, and the law, have changed fundamentally on this issue because of several factors: a growing body of scientific research that has enhanced our understanding of cetaceans’ complex intelligence and social behaviour and the negative effects of captivity on their welfare; media investigations by both professional and citizen journalists; and advocacy on behalf of the animals, including in the legislative arena and in the courts. * This article is current as of June 17, 2019. It has been partially updated to reflect the passage of Bill S-203 in June 2019. ** Katie Sykes is Associate Professor of Law at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. Her research focuses on animal law and on the future of the legal profession. She is co-editor, with Peter Sankoff and Vaughan Black, of Canadian Perspectives on Animals and the Law (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2015) the first book-length jurisprudential work to engage in a sustained analysis of Canadian law regulating the treatment of non-human animals at the hands of human beings. -

Relationship of Variable Oceanographic Factors to Migration and Survival of Fraser River Salmon

RELATIONSHIP OF VARIABLE OCEANOGRAPHIC FACTORS TO MIGRATION AND SURVIVAL OF FRASER RIVER SALMON 1. A. ROYAL International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission and J. P. TULLY Fisheries Research Board of Canada INTRODUCTION north through Queen Charlotte and Johnstone Straits. In 1957 it was noted that a larger share of Management of the various Fraser River salmon the population approached Vancouver Island from fisheries requires an intimate knowledge of the abund- the north, a larger percentage (approximately 16 ance and movements of salmon runs, which is drawn per cent) diverted through Queen Charlotte Strait largely from a detailed study of commercial catches. and it was also noted that the fish were slightly de- Abnormalities in abundance, in routes of migration layed, and migrated over a longer period of time. or times of occurrence, unless forecasted, may negate the beneficial effect of fishing regulations formulated In 1958, the sockeye run of approximately 19,000,- in advance of the fishing season. A flexible method of 000 fish failed to appear off the west coast of Van- regulatory adjustment during the course of fishing couver Island in its usual initial landfall and arrived may help rectify the adverse effects of vagaries in the northerly of Vancouver Island in the Queen Char- salmon population but it cannot be accepted as a lotte Sound area. The fish then moved in a southerly substitute for advance knowledge and planning. direction with an estimated thirty-five to forty per cent of the total population entering Queen Char- lotte Strait, thus approaching the Fraser River, from OCEANOGRAPHIC FACTORS AFFECTING the north instead of the usual route through the Juan SOCKEYE SALMON MIGRATIONS IN de Fuca Strait. -

A Comparison of British and American Treaties with the Klallam

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 1977 A comparison of British and American treaties with the Klallam Daniel L. Boxberger Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Boxberger, Daniel L., "A comparison of British and American treaties with the Klallam" (1977). WWU Graduate School Collection. 463. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/463 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. I acknowledge that I retain ownership rights to the copyright of this work, including but not limited to the right to use all or part of this work in future works, such as articles or books. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 W Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug

Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition 46 w Puget Sound – Point Partridge to Point No Point 50,000 Aug. 1995 July 2005 Port Townsend 25,000 47 w Puget Sound – Point No Point to Alki Point 50,000 Mar. 1996 Sept. 2003 Everett 12,500 48 w Puget Sound – Alki Point to Point Defi ance 50,000 Dec. 1995 Aug. 2011 A Tacoma 15,000 B Continuation of A 15,000 50 w Puget Sound – Seattle Harbor 10,000 Mar. 1995 June 2001 Q1 Continuation of Duwamish Waterway 10,000 51 w Puget Sound – Point Defi ance to Olympia 80,000 Mar. 1998 - A Budd Inlet 20,000 B Olympia (continuation of A) 20,000 80 w Rosario Strait 50,000 Mar. 1995 June 2011 1717w Ports in Juan de Fuca Strait - July 1993 July 2007 Neah Bay 10,000 Port Angeles 10,000 1947w Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound 139,000 Oct. 1893 Sept. 2003 2531w Cape Mendocino to Vancouver Island 1,020,000 Apr. 1884 June 1978 2940w Cape Disappointment to Cape Flattery 200,000 Apr. 1948 Feb. 2003 3125w Grays Harbor 40,000 July 1949 Aug. 1998 A Continuation of Chehalis River 40,000 4920w Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 Mar. 2005 - 4921w Queen Charlotte Sound to / à Dixon Entrance 525,000 Oct. 2008 - 4922w Vancouver Island / Île de Vancouver-Juan de Fuca Strait to / à Queen 525,000 Mar. 2005 - Charlotte Sound 4923w Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 Mar. -

Stopping the Use, Sale and Trade of Whales and Dolphins in Canada How Protection Is Consistent with WTO Obligations

Stopping the use, sale and trade of whales and dolphins in Canada How protection is consistent with WTO obligations Prepared by Leesteffy Jenkins, Attorney at Law 219 West Main St., P.O. Box 634 Hillsborough, NH 03244-0634 Phone (603) 464-4395 For ZOOCHECK CANADA INC. 3266 Yonge Street, Suite 1417 Toronto, Ontario M4N 3P6 (416) 285-1744 (p) (416) 285-4670 (f ) [email protected] www.zoocheck.com This legal analysis was commissioned by Zoocheck Canada as part of a research initiative looking into how trade laws impact the trade and use of whales and dolphins in Canada, and to educate the public about the same. Page 1 April 25, 2003 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a Canadian ban on the import and export of live cetaceans, wild-caught, captive born or those caught earlier in the wild and now considered captive, would violate Canada's obligations pursuant to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreements. CONCLUSION It is my understanding that there is currently no specific Canadian legislation banning the import/export of live cetaceans. Based on the facts* presented to me, however, it is my opinion that such legislation could be enacted consistent with WTO rules. This memorandum attempts to outline both the conditions under which Canadian regulation of trade in live cetaceans may be consistent with the WTO Agreements, as well as provide some guidance in the crafting of future legislation. PEER REVIEW & COMMENTS Chris Wold, Steve Shrybman, Esq Clinical Professor of Law and Director Sack, Goldblatt, Mitchell International Environmental Law Project 20 Dundas Street West, Ste 1130 Northwestern School of Law Toronto, Ontario M5G 2G8 Lewis and Clark College Tel.: (416) 979-2235 10015 SW Terwilliger Blvd Email: [email protected] Portland, Oregon, U.S.A. -

Research Plans for a Mid-Depth Cabled Seafloor Observatory in Western Canada

Special Issue—Ocean Observations Research Plans for a Mid-depth Cabled Seafloor Observatory in Western Canada Verena Tunnicliffe, Richard Dewey and Deborah Smith 5912 LeMay Road, Rockville, MD 20851-2326, USA. Road, 5912 LeMay The Oceanography machine, reposting, or other means without prior authorization of portion photocopy of this articleof any by Copyrigh Society. The Oceanography journal 16, Number 4, a quarterly of Volume in Oceanography, This article has been published VENUS Project University of Victoria • Victoria BC Canada As the first cabled seafloor observatory that Primary review, conducted by CFI, was based on the involves a geographically distributed network struc- quality of science proposed and the ultimate researcher ture, the Victoria Experimental Network Under the Sea group. It is, however, only the infrastructure that is fund- (VENUS) will oversee the deployment of three pow- ed and an initial operating stage. A major challenge for ered fiber-optic cable lines in British Columbia’s (B.C.) VENUS is to find subsequent operational funds and to southern waters. The funded infrastructure will offer encourage the development of user groups. Thus, to two-way high-speed communication access and inter- write the proposal we involved the users. Over 30 scien- action in 24-hour real time from the ocean floor and tists defined the mandate for VENUS and a subset craft- water column to a land based location. With an expect- ed the proposal that requested funding for cable and ed life of at least 20 years, each cable line will have a seafloor node installations, shore stations and data man- unique set of instrument suite combinations that will agement development plus some instruments to initiate reflect the environmental processes being studied by research activity. -

2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Island County, WA 122.164671W Inner Psge Pbell

48.435125N 48.449750N 123.134232W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: Island County, WA 122.164671W Inner Psge pbell Lk Cam LEGEND 5 Haro Strait Outer 5 Bay c S Ale k S SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE B A 0 a K y 5 N A N Federal American Indian J G Rosario Strait A Middle Chnnl U I L'ANSE RES 1880 U T Similk Bay Reservation J A N N 0 5 20 A 0 S 7 Off-Reservation Trust Land, 5 Mount Vernon T1880 5 S w Hawaiian Home Land Haro Strait Strait Haro 57 i 9 AGIT 0 n SK o SWINOMISH RES m Ska v Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, i gi i s t R 9 h 2 Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, SLAND 0 C KAW OTSA 5340 I h Tribal Designated Statistical Area SWINOMISH n n l RES 4075 Big State American Indian Tama Res 4125 SAMISH TDSA La Conner Lake Reservation State Designated Tribal Statistical Area Lumbee STSA 9815 T4075 Big Alaska Native Regional 5 Lk Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 SAN 055 JUAN State (or statistically NEW YORK 36 v equivalent entity) th Fo i ISLAND 029 r r R o k N S t k i ag g i a County (or statistically SAN JUAN 055 t R k iv S ERIE 029 equivalent entity) k r o F JEFFERSON 031 h t Minor Civil Division 20 u o 1,2 Bristol town 07485 S (MCD) Naval Air Conway Station Consolidated City Whidbey MILFORD 47500 Island Whidbey Island 534 Incorporated Place 1,3 Station 78155 Davis 18100 SAN JUAN 055 1 2 Census Designated Place (CDP) 3 Incline Village 35100 CLALLAM 009 534 9 Census Tract 33.07 Lake McMurray h h g g u u o o l l S S Skagit Bay t e Naval Air Station a r DESCRIPTION SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL o o Whidbey Island m b o Oak Harbor 50360 tea M S (Seaplane Base) om Interstate 3 Water Body Pleasant Lake T SKAGIT 057 U.S. -

State of the Physical, Biological and Selected Fishery Resources of Pacific Canadian Marine Ecosystems in 2016

State of the Physical, Biological and Selected Fishery Resources of Pacific Canadian Marine Ecosystems in 2016 Peter C. Chandler, Stephanie A. King and Jennifer Boldt (Editors) Fisheries & Oceans Canada Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 West Saanich Rd. Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 Canada 2017 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 3225 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique.