The Case of Temuco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vegetation of Robinson Crusoe Island (Isla Masatierra), Juan

The Vegetation ofRobinson Crusoe Island (Isla Masatierra), Juan Fernandez Archipelago, Chile1 Josef Greimler,2,3 Patricio Lopez 5., 4 Tod F. Stuessy, 2and Thomas Dirnbiick5 Abstract: Robinson Crusoe Island of the Juan Fernandez Archipelago, as is the case with many oceanic islands, has experienced strong human disturbances through exploitation ofresources and introduction of alien biota. To understand these impacts and for purposes of diversity and resource management, an accu rate assessment of the composition and structure of plant communities was made. We analyzed the vegetation with 106 releves (vegetation records) and subsequent Twinspan ordination and produced a detailed colored map at 1: 30,000. The resultant map units are (1) endemic upper montane forest, (2) endemic lower montane forest, (3) Ugni molinae shrubland, (4) Rubus ulmifolius Aristotelia chilensis shrubland, (5) fern assemblages, (6) Libertia chilensis assem blage, (7) Acaena argentea assemblage, (8) native grassland, (9) weed assemblages, (10) tall ruderals, and (11) cultivated Eucalyptus, Cupressus, and Pinus. Mosaic patterns consisting of several communities are recognized as mixed units: (12) combined upper and lower montane endemic forest with aliens, (13) scattered native vegetation among rocks at higher elevations, (14) scattered grassland and weeds among rocks at lower elevations, and (15) grassland with Acaena argentea. Two categories are included that are not vegetation units: (16) rocks and eroded areas, and (17) settlement and airfield. Endemic forests at lower elevations and in drier zones of the island are under strong pressure from three woody species, Aristotelia chilensis, Rubus ulmifolius, and Ugni molinae. The latter invades native forests by ascending dry slopes and ridges. -

Earthquake List

1. Valdivia, Chile, May 22, 1960: 9.5 Number killed: 1,655 Number displaced: 2 million Cost of damages: $550 million The world's largest earthquake produced landslides so massive that they changed the courses of rivers and lakes. It begot a tsunami that battered the northern coastline of California, some 9,000 miles away; waves also hit Hawaii, the Philippines, and Japan where hundreds died. 2. Prince William Sound, Alaska. March 28, 1964: 9.2 Number killed: 128 Number displaced: Unknown Cost of damages: $311 million Because it occurred on Good Friday, it earned the somewhat dubious (if logical) title of the "Good Friday Earthquake." 3. The west coast of Northern Sumatra, Indonesia, December 26, 2004: 9.1 Number killed: 157,577 Number displaced: 1,075,350 Cost of damages: Unknown The tsunami that followed caused more casualties than any in recorded history. 4. Kamchatka, Russia, November 5, 1952: 9.0 Number killed: Unknown Number displaced: Unknown Cost of damages: $800,000 to $1 million This earthquake unleashed a tsunami that was "powerful enough to throw a cement barge in the Honolulu Harbor into a freighter," but it wasn't widely reported in the West because it happened during the Cold War. 5. Off the coast of Ecuador, January 31, 1906: 8.8 Number killed: 500 to 1,500 Number displaced: Unknown Cost of damages: Unknown An especially violent year for earthquakes, 1906 also saw massive tremors in San Francisco and in Valparaiso, Chile. 6. Rat Islands, Alaska, February 4, 1965: 8.7 Number killed: Unknown Number displaced: Unknown Cost of damages: $10,000 Positioned on the Aleutian arc on the boundary between the Pacific and North American crustal plates, the Rat Islands occupy one of the world's most active seismic zones; with more than 100 7.0 or larger magnitude earthquakes having occurred there in the past 100 years. -

Crustal Deformation Associated with the 1960 Earthquake Events in the South of Chile

Paper No. CDDFV CRUSTAL DEFORMATION ASSOCIATED WITH THE 1960 EARTHQUAKE EVENTS IN THE SOUTH OF CHILE Felipe Villalobos 1 ABSTRACT Large earthquakes can cause significant subsidence and uplifts of one or two meters. In the case of subsidence, coastal and fluvial retaining structures may therefore no longer be useful, for instance, against flooding caused by a tsunami. However, tectonic subsidence caused by large earthquakes is normally not considered in geotechnical designs. This paper describes and analyses the 1960 earthquakes that occurred in the south of Chile, along almost 1000 km between Concepción and the Taitao peninsula. Attention is paid to the 9.5 moment magnitude earthquake aftermath in the city of Valdivia, where a tsunami occurred followed by the overflow of the Riñihue Lake. Valdivia and its surrounding meadows were flooded due to a subsidence of approximately 2 m. The paper presents hypotheses which would explain why today the city is not flooded anymore. Answers can be found in the crustal deformation process occurring as a result of the subduction thrust. Various hypotheses show that the subduction mechanism in the south of Chile is different from that in the north. It is believed that there is also an elastic short-term effect which may explain an initial recovery and a viscoelastic long-term effect which may explain later recovery. Furthermore, measurements of crustal deformation suggest that a process of stress relaxation is still occurring almost 50 years after the main seismic event. Keywords: tectonic subsidence, 1960 earthquakes, Valdivia, crustal deformation, stress relaxation INTRODUCTION Tectonic subsidence or uplift is not considered in any design of onshore or near shore structures. -

The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010

EERI Special Earthquake Report — June 2010 Learning from Earthquakes The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010 From March 6th to April 13th, 2010, mated to have experienced intensity ies of the gap, overlapping extensive a team organized by EERI investi- VII or stronger shaking, about 72% zones already ruptured in 1985 and gated the effects of the Chile earth- of the total population of the country, 1960. In the first month following the quake. The team was assisted lo- including five of Chile’s ten largest main shock, there were 1300 after- cally by professors and students of cities (USGS PAGER). shocks of Mw 4 or greater, with 19 in the Pontificia Universidad Católi- the range Mw 6.0-6.9. As of May 2010, the number of con- ca de Chile, the Universidad de firmed deaths stood at 521, with 56 Chile, and the Universidad Técni- persons still missing (Ministry of In- Tectonic Setting and ca Federico Santa María. GEER terior, 2010). The earthquake and Geologic Aspects (Geo-engineering Extreme Events tsunami destroyed over 81,000 dwell- Reconnaissance) contributed geo- South-central Chile is a seismically ing units and caused major damage to sciences, geology, and geotechni- active area with a convergence of another 109,000 (Ministry of Housing cal engineering findings. The Tech- nearly 70 mm/yr, almost twice that and Urban Development, 2010). Ac- nical Council on Lifeline Earthquake of the Cascadia subduction zone. cording to unconfirmed estimates, 50 Engineering (TCLEE) contributed a Large-magnitude earthquakes multi-story reinforced concrete build- report based on its reconnaissance struck along the 1500 km-long ings were severely damaged, and of April 10-17. -

200911 Lista De EDS Adheridas SCE Convenio GM-Shell

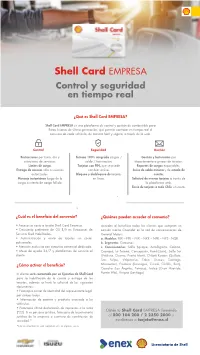

Control y seguridad en tiempo real ¿Qué es Shell Card EMPRESA? Shell Card EMPRESA es una plataforma de control y gestión de combustible para flotas livianas de última generación, que permite controlar en tiempo real el consumo de cada vehículo, de manera fácil y segura, a través de la web. Restricciones por hora, día y Sistema 100% integrado cargas / Gestión y facturación por estaciones de servicios. saldo / facturación. departamento o grupos de tarjetas. Límites de carga. Tarjetas con PIN, que se puede Reportes de cargas exportables. Entrega de accesos sólo a usuarios cambiar online. Aviso de saldo mínimo y de estado de autorizados. Bloqueo y desbloqueo de tarjetas cuenta. Mensaje instantáneo luego de la en línea. Solicitud de nuevas tarjetas a través de carga o intento de carga fallida. la plataforma web. Envío de tarjetas a todo Chile sin costo. ¿Cuál es el beneficio del convenio? ¿Quiénes pueden acceder al convenio? • Acceso sin costo a tarjeta Shell Card Empresa. Acceden al beneficio todos los clientes que compran un • Descuento preferente de -20 $/lt en Estaciones de camión marca Chevrolet en la red de concesionarios de Servicio Shell Habilitadas. General Motors. • Administración y envío de tarjetas sin costos a. Modelos: FRR – FTR – FVR – NKR – NPR – NPS - NQR. adicionales. b. Segmento: Camiones. • Atención exclusiva con ejecutivo comercial dedicado. c. Concesionarios: Salfa (Iquique, Antofagasta, Calama, • Mesa de ayuda 24/7 y plataformas de servicio al Copiapó, La Serena, Concepción, Rondizzoni), Salfa Sur cliente. (Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Chiloé) Kovacs (Quillota, San Felipe, Valparaíso, Talca, Linares, Santiago, ¿Cómo activar el beneficio? Movicenter), Frontera (Rancagua, Curicó, Chillán, Buin), Coseche (Los Ángeles, Temuco), Inalco (Gran Avenida, El cliente será contactado por un Ejecutivo de Shell Card Puente Alto), Vivipra (Santiago). -

Viith NEOTROPICAL ORNITHOLOGICAL CONGRESS

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 13: 221–224, 2002 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NEWS—NOTICIAS—NOTÍCIAS VIIth NEOTROPICAL ORNITHOLOGICAL CONGRESS Dates. – The VIIth Neotropical Ornitholog- although they know a few English words and ical Congress will take place from Sunday, attempts to communicate by non-Spanish 5 October through Saturday 11 October speakers will result in a meaningful exchange. 2003. Working days will be Monday 6, Puerto Varas has several outstanding restau- Tuesday 7, Wednesday 8, Friday 10, and rants (including sea food, several more ethnic Saturday 11 October 2003. Thursday 9 kinds of food, and, of course, Chilean fare). October 2003 will be a congress free day. In spite of its small size, Puerto Varas is quite After the last working session on Saturday 11 a cosmopolitan town, with a well-marked October, the congress will end with a ban- European influence. There are shops, bou- quet, followed by traditional Chilean music tiques, and other stores, including sporting and dance. goods stores. Congress participants will be able to choose from a variety of lodging alter- Venue. – Congress Center, in Puerto Varas, natives, ranging from luxury five-star estab- Xth Region, Chile (about 10 km N of Puerto lishments to ultra-economical hostels. Montt, an easy to reach and well-known Because our meeting will be during the “off ” travel destination in Chile. The Congress Cen- season for tourists, participants will be able to ter, with its meeting rooms and related facili- enjoy the town’s tourist-wise facilities and ties, perched on a hill overlooking Puerto amenities (e.g., the several cybercafes, compet- Varas, is only an 800-m walk from downtown itive money exchange businesses, and the where participants will lodge and dine in their many local tour offerings) without paying typ- selection of hotels, hostels, and eating facili- ical tourist prices. -

Chile & Argentina

Congregation Etz Chayim of Palo Alto CHILE & ARGENTINA Santiago - Valparaíso - Viña del Mar - Puerto Varas - Chiloé - Bariloche - Buenos Aires November 3-14, 2021 Buenos Aires Viña del Mar Iguazú Falls Post-extension November 14-17, 2021 Devil’s throat at Iguazu Falls Join Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky for an unforgettable trip! 5/21/2020 Tuesday November 2 DEPARTURE Depart San Francisco on overnight flights to Santiago. Wednesday November 3 SANTIGO, CHILE (D) Arrive in Santiago in the morning. This afternoon visit the Plaza de Armas, Palacio de la Moneda, site of the presidential office. At the end of the day take the funicular to the top of Cerro San Cristobal for a panoramic view of the city followed by a visit to the Bomba Israel, a firefighter’s station operated by members of the Jewish Community. Enjoy a welcome dinner at Restaurant Giratorio. Overnight: Hotel Novotel Providencia View from Cerro San Cristóbal - Santiago Thursday November 4 VALPARAÍSO & VIÑA del MAR (B, L) Drive one hour to Valparaíso. Founded in 1536 and declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003, Valparaíso is Chile’s most important port. Ride some of the city’s hundred-year-old funiculars that connect the port to the upper city and visit Pablo Neruda’s home, “La Sebastiana”. Enjoy lunch at Chez Gerald continue to the neighboring city of. The “Garden City” was founded in 1878 and is so called for its flower-lined avenues. Stroll along the city’s fashionable promenade and visit the Wulff Castle, an iconic building constructed in neo-Tudor style in 1906. -

Republic of Chile March 2020

Market Report: REPUBLIC OF CHILE April 2020 OceanX - Version 1.9 / April 2020 1.9 - Version OceanX Market Report: Republic of Chile March 2020 Country Pro*ile: Capital: Santiago Population: (2017) 18,729,160 Area: 756,096.3 km2 Of*icial Language: Spanish Currency Unit: Chilean peso 1USD: 865.70CLN GDP (Current, 2018): $ 298.231 (Billion) GDP per capita (2018): $ 15,923.3 GDP Growth Rate (2018): Annual: 4.0 % In*lation Rate (2018): 2.6% Unemployment Rate(2018): 7.2% Tax Revenue 18.2% Imports of Goods and services ( % of GDP): 28.7 % Exports of Goods and services ( % of GDP): 28.8 % * (Source World Bank Data) Corporate tax: 25% Income Tax: 0-35.5% Standard VAT rate: 19% The economy seemed to be recovering in the 1st Q of 2020 after last year social tensions. GDP growth was expected to reach 3.02 % by end of the year, and Exports are also expected to raise although uncertain global demand due to the Covid-19 Pandamic. The GDP growth forecast, however, is declining every month as impact of the global pandemic is becoming more considerable. T +41 62 544 94 10 E [email protected] I oceanx.network OceanX AG, Fluhgasse 135, 5080 Laufenburg, Switzerland General Facts: The economy of Chile, which is one of the fastest developing economies of Latin America and the world's largest copper producer, is based on more mineral exports, especially copper. Chile's main imported items are petroleum and petroleum products, chemicals, electrical and telecommunications vehicles, industrial machinery, vehicles and natural gas. Chile is the 1st country in Latin American that has adopted the free market economy model, has political and economic stability, and acts with the understanding of free and competitive trade with all countries of the world. -

VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo

1 VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Biografía Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Entre 1986 y 1991 estudió Licenciatura en Arte, Mención Dibujo, en la Universidad Católica de Chile. Al terminar sus estudios regresó a Talcahuano, donde creó su taller de arte en los años noventa y destacó en distintos salones nacionales. A mediados de la década se trasladó a Santiago, ciudad en la que entre 1995 y 2003 realizó clases de pintura. Su trabajo como pintor, que ha sido expuesto en Chile y en el extranjero, aborda diversos temas y estilos como naturalezas muertas, paisajes de corte expresionista y, más recientemente, ha explorado las posibilidades de la abstracción. Además, es socio fundador del Foto Cine Club de la Universidad de Temuco, inaugurado en 1987. El artista reside en Santiago, Chile. Premios, distinciones y concursos 2013 Premio in situ Ricardo Anwanter categoría figurativo y mención honrosa categoría envío, XXX Salón Internacional Valdivia y su Río, Valdivia, Chile. 2011 Segundo lugar, Concurso Nacional Pinceladas Contra Viento y Marea, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 2000 Tercer lugar especialidad Pintura, X versión del Concurso nacional de pintura El color del sur, Santiago, Chile. 1999 Tercer lugar, Segundo Salón Nacional de Pintura Invierno-Primavera, Instituto Chileno Japonés de Cultura, Santiago, Chile. 2 1999 Premio Municipal de Arte, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 1994 Mención Especial In Situ, El color del sur, Puerto Varas, Chile. 1993 Primer Premio en Pintura, Empresas Empremar, Valparaíso, Chile. -

210315 Eds Adheridas Promo Ilusión Copia

SI ERES TRANSPORTISTA GANA UN K M Disponible Estaciones de servicios Shell Card TRANSPORTE Dirección Ciudad Comuna Región Pudeto Bajo 1715 Ancud Ancud X Camino a Renaico N° 062 Angol Angol IX Antonio Rendic 4561 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Caleta Michilla Loteo Quinahue Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 8450 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Panamericana Norte Km. 1354, Sector La Negra Antofagasta Antofagasta II Av. Argentina 1105/Díaz Gana Antofagasta Antofagasta II Balmaceda 2408 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 10615 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Camino a Carampangue Ruta P 20, Número 159 Arauco Arauco VIII Camino Vecinal S/N, Costado Ruta 160 Km 164 Arauco Arauco VIII Panamericana Norte 3545 Arica Arica XV Av. Gonzalo Cerda 1330/Azola Arica Arica XV Av. Manuel Castillo 2920 Arica Arica XV Ruta 5 Sur Km.470 Monte Águila Cabrero Cabrero VII Balmaceda 4539 Calama Calama II Av. O'Higgins 234 Calama Calama II Av. Los Héroes 707, Calbuco Calbuco Calbuco X Calera de Tango, Paradero 13 Calera de Tango Santiago RM Panamericana Norte Km. 265 1/2 Sector de Huentelauquén Canela Coquimbo IV Av. Presidente Frei S/N° Cañete Cañete VIII Las Majadas S/N Cartagena Cartagena V Panamericana Norte S/N, Ten-Ten Castro Castro X Doctor Meza 1520/Almirante Linch Cauquenes Cauquenes VII Av. Americo Vespucio 2503/General Velásquez Cerrillos Santiago XIII José Joaquín Perez 7327/Huelen Cerro Navia Santiago XIII Panamericana Norte Km. 980 Chañaral Chañaral III Manuel Rodríguez 2175 Chiguayante Concepción VIII Camino a Yungay, Km.4 - Chillán Viejo Chillán Chillán XVI Av. Vicente Mendez 1182 Chillán Chillán XVI Ruta 5 Sur Km. -

Baltazar Hernández Baltazar Hernández

1 Baltazar Hernández Baltazar Hernández Biografía Baltazar Hernández Romero, pintor, acuarelista. Nació en Ñuble, Chile, el 8 de Agosto de 1924, y falleció en Chillán, Chile, el 13 de enero de 1997. En 1943 egresó de la Escuela Normal de Chillán. Ejerció la docencia en la asignatura de Artes Plásticas en la Enseñanza Secundaria, Normalista y Universitaria. Inició su formación artística con los profesores pintores Oscar Hernández, Armando Sánchez y Oscar Gacitúa . Más tarde realizó cursos de Arte y de Pedagogía en las escuelas de temporada de la Universidad de Chile, y de la Universidad de Concepción. En general su formación profesional y artística es autodidacta. Fue miembro de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes Tanagra , donde presidió varios periodos. Fue socio de la Asociación de pintores y escritores de Chile. Premios y distinciones 1948 Primer Premio Salón Regional de Talca, Chile. 1950 Tercer Premio Acuarela Salón Nacional 4to Centenario de Concepción, Chile. 1957 Premio de Honor Salón Anual de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes Tanagra, Chillán, Chile. 1959 Premio Municipal de Extensión Cultural y Artística, Municipalidad de Chillán, Chile. 1966 Primer Premio, Medalla de Oro, IV Salón de Artes Plásticas Club de la República, Santiago, Chile. 1976 Mención Honrosa, Certamen Nacional Chileno de Artes Plásticas, Santiago, Chile. 1982 Mención Honrosa, Salón Nacional de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile. 1991 Mención Honorífica en Acuarela, Salón Nacional de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile. 1992 Mención Honorífica en Acuarela, Salón Nacional de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile. 1993 Tercera Medalla en Acuarela, Salón Nacional de la Sociedad de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile. -

Hotel. Herzog Blanco 395, Valparaiso

CHILE-continued ,'Na.me. Address. Na/ll'le. Address. Hamdorf y Cia. Arturo Prat 692, esq. Ant. Varas, Imprenta Mercantil Blanco 1609, Casilla 1394, Val- Casilla 27D, Temlico, 'and all paraiso. branches in Chile. Imprenta Valdivia Guillermo Aguilar, Valdivia. Hamdorf Matzen, Jacob H. , Arturo Prat 692, Temuco. Iinprenta Victoria Chacabuco 1781, Valparaiso. Hammersley, Antonio Ahumada 215, and Constanza Indoo, Zonji Santiago. 618, Santiago. Indunacion Wagner-Beckers y R. Philippi 341, Casilla 125, Val- Hammersley, Hnos. Esmeralda 1118, Valparaiso,and Cia., Ltda. paraiso. Ahumada 215, Santiago. Industrial y Maderera Rio Corren Puerto Montt. Hammersley, Victor Esmeralda lll8, Valparaiso, and · toso, Soc. Callao 146, Vina del Mar. · Industrial Wenz y · Cia., Agelin Santiago. Hampel & Kosiel Ltda. Santo Domingo 1031, Santiago. dus, Soc. Hargo, Casa EsmeraJda 970, Valparaiso, and Instituto Cultural Germano- Agustinas 975, and Pasaje Matte Valparaiso 464, Vina del Mar. ' Chileno 82, Santiago. Harms Steffens, Enrique Lota Bajo. Islah (La Reforma) Bellwvista 263, Santiago. Hartung, Alfredo J. Esmeralda 970, Valparaiso. Italcable Santiago. · Hartung Drechsler, Enrique Aguirre 1203, Santiago. "Italmar;" S.A. de Empresas Valparaiso and Santiago. - Hattori Itinoze, Motoso Ave. Vicuna Mackenna 4, San- Maritimas tiago. Italradio Ltda. Chacabu:co 2052, Valparaiso. Hauser, Carlos Chacabuco 142, Concepcion. Itoh Ltda., Casa (Chile) Nueva York 52, Casilla 1657, Hauser Venegas, Tito Bulnes 635, Temuco. Santiago, and at Valparaiso, " Hiwastele " Agencia N oticiosa Agustinas 713, Santiago. 'Iwasaki, Tomas Vivar 939, Iquique. Hebel Haubrich, Rodolfo · Frutillar. Jacob, A. & Co. Ahumada 23, Casilla 3963, San Heck Munzenmeyer, Gustavo A. Varas 529, Casilla 314, Puerto tiago, and all bran:Qhes .• in Montt. Chile. Heesch Bolten, Walter Ave.