The Growth of a Shadow Banking System in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Indiaq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCLAT Pulls up MCA, IL&FS Board for Delay in Resolution

6 ECONOMY & PUBLIC AFFAIRS MUMBAI | FRIDAY, 9 AUGUST 2019 1 > RBI TASK FORCE ON OFFSHORE RUPEE MARKETS SUBMITS REPORT NCLAT pulls up MCA, IL&FS Panel for easier foreign board for delay in resolution Appellate tribunal asks them to file progress report latest by September 3 AASHISH ARYAN day basis to ensure that the total New Delhi, 8 August process with regard to all the play in currency market amber entities". The National Company Law "They will keep it in mind ANUP ROY USHA THORAT PANEL Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) on that already 300 days approx Mumbai, 8 August Thursday pulled up the have completed since the inter- SUGGESTIONS Ministry of Corporate Affairs im order was passed on 15th Reserve Bank of India (RBI)- Extend onshore market (MCA) and the newly appointed October, 2018," the NCLAT appointed task force on offshore hours to improve access board of Infrastructure Leasing said, adding that a fresh rupee markets has recommended & Financial Services (IL&FS) for progress report should be filed A of overseas users that Indian banks be allowed to “freely inordinate delay in presenting by September 3. offer prices to non-residents” and extend Allow Indian banks to the final resolution plan for the On February 11, the central local market timings to match that of freely offer prices to debt-laden firm. government and the new board the offshore derivatives markets to take global clients around "In spite of our order dated of IL&FS had submitted an affi- the sting out of the speculative positions 12th July, 2019, no progress davit detailing three categories the clock taken there. -

Starred Articles

GKCA Update st th 1 to 30 June Starred Articles 05 CII announces 10-point plan for economic revival June Economy > GDP India The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) voiced its concern over the stagnant state of the Indian economy and in a bid to rescue her, has unveiled a 10-point agenda for its revival. The remedies include fast-tracking the implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and easing of FDI (foreign direct investment) regulations in aviation and other sectors. Addressing a press conference on 5th June 2012, CII President, Adi B. Godrej, said that the primary concern for the nation was its GDP growth rate which was a mere 5.37 per cent in the last quarter was lowest in nine years. Some of the important reform to improve GDP growth as suggested by him are - early introduction of GST, the Government and the RBI inclusion of a strong monetary stimulus, correcting the current account deficit by encouraging exports and containing imports, arresting rupee slide, reducing subsidies, implementing financial sector reforms and removing bottlenecks in infrastructure growth. 06 Venus Transits between Sun and Earth June World > Space Planet Venus passed directly between the Sun and Earth on 6 June 2012, an astronomical rarity that sky watchers were eager to witness. Such a transit will not occur until 2117. The Transit of Venus, as it is called, appeared like a small dot on the Sun's elaborate circumference. This transit, which bookended a 2004-2012 pair, began at 6:09 p.m. EDT (2209 GMT) and lasted for six hours and 40 minutes. -

Dear Aspirant with Regard

DEAR ASPIRANT HERE WE ARE PRESENTING YOU A GENRAL AWERNESS MEGA CAPSULE FOR IBPS PO, SBI ASSOT PO , IBPS ASST AND OTHER FORTHCOMING EXAMS WE HAVE UNDERTAKEN ALL THE POSSIBLE CARE TO MAKE IT ERROR FREE SPECIAL THANKS TO THOSE WHO HAS PUT THEIR TIME TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN A IN ON LIMITED RESOURCE 1. NILOFAR 2. SWETA KHARE 3. ANKITA 4. PALLAVI BONIA 5. AMAR DAS 6. SARATH ANNAMETI 7. MAYANK BANSAL WITH REGARD PANKAJ KUMAR ( Glory At Anycost ) WE WISH YOU A BEST OF LUCK CONTENTS 1 CURRENT RATES 1 2 IMPORTANT DAYS 3 CUPS & TROPHIES 4 4 LIST OF WORLD COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITAL 5 5 IMPORTANT CURRENCIES 9 6 ABBREVIATIONS IN NEWS 7 LISTS OF NEW UNION COUNCIL OF MINISTERS & PORTFOLIOS 13 8 NEW APPOINTMENTS 13 9 BANK PUNCHLINES 15 10 IMPORTANT POINTS OF UNION BUDGET 2012-14 16 11 BANKING TERMS 19 12 AWARDS 35 13 IMPORTANT BANKING ABBREVIATIONS 42 14 IMPORTANT BANKING TERMINOLOGY 50 15 HIGHLIGHTS OF UNION BUDGET 2014 55 16 FDI LLIMITS 56 17 INDIAS GDP FORCASTS 57 18 INDIAN RANKING IN DIFFERENT INDEXS 57 19 ABOUT : NABARD 58 20 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 58 21 OSCAR AWARD 2014 59 22 STATES, CAPITAL, GOVERNERS & CHIEF MINISTERS 62 23 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 62 23 LIST OF IMPORTANT ORGANIZATIONS INDIA & THERE HEAD 65 24 LIST OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND HEADS 66 25 FACTS ABOUT CENSUS 2011 66 26 DEFENCE & TECHNOLOGY 67 27 BOOKS & AUTHOURS 69 28 LEADER”S VISITED INIDIA 70 29 OBITUARY 71 30 ORGANISATION AND THERE HEADQUARTERS 72 31 REVOLUTIONS IN AGRICULTURE IN INDIA 72 32 IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA 73 33 CLASSICAL DANCES IN INDIA 73 34 NUCLEAR POWER -

Non-Banking Finance Companies: the Changing Landscape

Contents Foreword P2/ Message from ASSOCHAM P4/ NBFC market context P6/ Alternative credit scoring P8/ NBFC Regulations P15 / Recent trends in funding sources for NBFCs P23 Non-Banking Finance Companies: The Changing Landscape www.pwc.in Foreword from PwC In countries such as the US and UK, large credit bureaus like Equifax, Experian and TransUnion furnish lenders with credit scores primarily based on the loan applicants’ past repayment data. These credit bureaus have also set up shop in India over the last decade, along with other players such as Credit Information Bureau India Limited (CIBIL) and CRIF High Mark. These players operate by leveraging sophisticated data-capturing and sharing capabilities to gather, store and share accurate loan and repayment history. This reliance on traditional credit infrastructure presents a signifi cant lending challenge in India, where bureau data is often incomplete, if not altogether unavailable. According to the World Bank, less than 1 in 10 people in low- and middle- income countries around the world have a documented credit history. The World Bank has endorsed the use of reported non-fi nancial data in the credit origination processes and considers it a powerful tool for driving fi nancial inclusion in emerging markets. More recently, in the Financial Inclusion 2020 (FI 2020) roadmap, Accion highlighted the great value of alternative data as an instrument to increase fi nancial inclusion and help achieve their FI 2020 objectives. Currently, payment history, amounts owed, length of credit history, new credit taken and types of credit used form the basis of credit analysis for most non-banking fi nance companies (NBFCs). -

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL US AT 1 [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Index (Current Affairs) Part -1 1. Scheme (State gov/ Central Gov) (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 2. Important Summit/Meeting (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 3. Appointment (National/ International/ Brand ambassador) (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 4. Web Portal/ Application 5. Awards (Important Award, 64th Filmfare Awards 2019, Bhart rattan, Padma Vibhsan, Pdma bhusan, , Nobel price 2018, Oscar award, ) 6. India’s Ranking Index 7. Loan 8. Company Merger List (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 9. Budget (2019) 10. Economics Survey 2018-19 11. Partnership and Agreement (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 12. Important MoU (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 13. Defence News (Covered 1st March to 24th July 2019) 14. Important Current Affairs in short (Covered 1st March to 24th July 2019) 15. Important Banking and finance in short(Covered 1st March to 24th July 2019) 16. GDP FORCASTING 17. Payment Bank, Public bank, Private bank, Small Finacial bank CEO, Headquater and Tagline 18. Obituary 19. Book and Author 20 Sports Affaris (Covered 1st Feb to 24th July 2019) 21. Up coming Sport Event Venue 22. Important Days and Theme 23. State-CM-Goverment 24. Union Cabinet Minister and Secretary Part 2 (Static GK) 1. Important Dam in India 2. Major Sea port AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL US AT 2 [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel 3. Lake (State –wise) 4. -

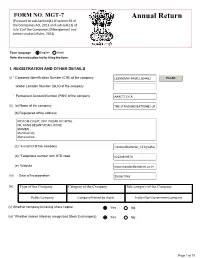

Annual Return [Pursuant to Sub-Section(1) of Section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and Sub-Rule (1) of Rule 11Of the Companies (Management And

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No (f) Specify the reasons for not holding the same II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 0 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company III. -

Sbi Po / Clerk 2019 Capsule

SBI PO / CLERK 2019 CAPSULE Exclusively prepared for RACE students PAGE : 64 | | PRICE : NOT FOR SALE (JANUARY-JUNE 2019) TOPIC : SBI PO / CLERK CAPSULE SBI PO/CLERK 2019 CAPSULE (JANUARY – JUNE 2019) INDEX TOPIC Page No BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS 2 LIST OF INDEXES BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 7 GDP FORECAST OF INDIA BY VARIOUS ORGANISATION 8 RANKINGS / REPORTS BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 8 LIST OF VARIOUS COMMITTEE & ITS HEAD 11 LOAN SANCTIONED BY NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL BANKS TO INDIA 12 PENALITY IMPOSED BY RBI TO VARIOUS BANKS IN INDIA 13 LIST OF ACQUISTION & MERGER TOOK PLACE FROM JAN – JUNE 2019 13 APPS/SCHEMES/FACILITY LAUNCHED BY VARIOUS BANKS/ORGANISATIONS/COMPANY 13 NATIONAL NEWS 15 STATE NEWS 20 IIT’S IN NEWS 26 NATIONAL SUMMITS 26 INTERNATIONAL NEWS 30 INTERNATIONAL SUMMITS 34 LIST OF AGREEMENTS/MOU’S SIGNED BY INDIA WITH VARIOUS COUNTRIES 37 APPOINTMENTS / RESIGNATION /RETIREMENT / BRAND AMBASSADORS 38 AWARDS & HONOURS 41 BOOKS & AUTHORS 48 SPORTS NEWS 48 IMPORTANT EVENTS OF THE DAY 57 OBITUARY 60 CABINET MINISTERS 2019 / LIST OF MINISTERS OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE)/ LIST OF 61 MINISTERS OF STATE INTERIM BUDGET 2019-20 62 ________________________________________________________ RACE Coaching Institute for Banking and Government Jobs 7601808080 / 9043303030 www. RACEInstitute. in Courses Offered : BANK | SSC | RRB | TNPSC |KPSC | SBI PO & CLERK 2019 CAPSULE | 2 BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS framework allowing them to resume their normal lending activities subject RBI IN NEWS to certain conditions and continuous monitoring. ➢ Second Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2019-20 Resolution ➢ The Reserve Bank has imposed monetary penalty of two million rupees of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) Reserve Bank of India. -

Chronology of Major Policy Initiatives by Sebi

This Report is in conformity with the format as per the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Annual Report) Rules, 1994, notified in Official Gazette on April 7, 1994. 1 3 MEMBERS OF THE BOARD (As on March 31, 2010) C B BHAVE CHAIRMAN Members appointed under Section 4(1)(d) of the SEBI Act, 1992 (15 of 1992) M S SAHOO WHOLE TIME MEMBER K M ABRAHAM WHOLE TIME MEMBER PRASHANT SARAN WHOLE TIME MEMBER G MOHAN GOPAL Director National Judicial Academy Bhopal T V MOHANDAS PAI Director Infosys Technologies Limited Bangalore Members nominated under Section 4(1)(b) of the SEBI Act, 1992 (15 of 1992) R BANDYOPADHYAY Secretary Ministry of Corporate Affairs Government of India K P KRISHNAN Joint Secretary Ministry of Finance Department of Economic Affairs Government of India Member nominated under Section 4(1)(c) of the SEBI Act, 1992 (15 of 1992) USHA THORAT Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India 5 MEMBERS OF THE SEBI BOARD (As on March 31, 2010) C B BHAVE Chairman M S SAHOO K M ABRAHAM PRASHANT SARAN G MOHAN GOPAL Whole Time Whole Time Whole Time Director Member Member Member National Judicial Academy Bhopal T V MOHANDAS PAI R BANDYOPADHYAY K P KRISHNAN USHA THORAT Director Secretary Joint Secretary Deputy Governor Infosys Technologies Ministry of Corporate Ministry of Finance Reserve Bank of India Limited Affairs Department of Economic Bangalore Government of India Affairs 7 Government of India CHAIRMAN, WHOLE TIME MEMBERS AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS Left to Right : Sitting : Dr. K.M. Abraham, Whole Time Member, Shri C.B. -

Deepak Bhardwaj = Cleared 6 Government Jobs

FULL CA – JAN 2020 Ask questions on Quora – click on logo SUBSCRIBE YT channel - click on logo CLICK HERE TO VISIT OUR FREE WEBSITE CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD FREE PDFs FROM WEBSITE CLICK HERE TO WATCH ALL YOUTUBE VIDEOS LINKS CLICK HERE TO JOIN OUR DAILY QUIZ GROUP CLICK HERE TO LEARN QUICKLY FROM DAILY FLASH CA IMAGES 2 Copyright © 2020 BANKERSHALA (spread the knowledge) - All Rights Reserved– DEEPAK BHARDWAJ = CLEARED 6 GOVERNMENT JOBS YOUTUBE VIDEOS – CLICK HERE TO WATCH LAST MINUTE TIPS (APPLICABLE FOR ALL EXAMS) (600+ VIEWS) MY VIEWS ON CHANGE IN THE IBPS EXAM INTERFACE (200+ VIEWS) SUMMIT/EVENTS/CONFRENCES ETC DELHI - National Traders Convention organised by Confederation of All India Traders - South Asian Trade and Travel Exchange Expo (SATTE) 2020 - 6th meeting of the Island Development Agency (IDA) - India-Bangladesh Information and Broadcasting Ministers’ Meet 2020 - Conference of the Chief Secretaries and Administrator State and Union Territories on Census 2021 - International Summit on Women in STEM “Visualizing the Future: New Skylines” - NIC Tech Conclave-2020, theme - “Technologies for Next-Gen Governance” 3 Copyright © 2020 BANKERSHALA (spread the knowledge) - All Rights Reserved– DEEPAK BHARDWAJ = CLEARED 6 GOVERNMENT JOBS - World Sustainable Summit 2020, theme - ‘Towards 2030: Making the Decade Count’ - Border Coordination Conference between border guarding forces of India and Bangladesh - India will host the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Council of Heads of Government meeting 2020. NORTH Jammu - 3rd edition -

Power Minister RK Singh, Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari

FACTORS TO WATCH 10:00 am: Power Minister R.K. Singh, Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari, New & Renewable Energy Secretary Indu Shekhar Chaturvedi, Petroleum Secretary Tarun Kapoor, Tata Steel Managing Director and CII President T.V. Narayan, Tata Power Chief Executive and Managing Director Praveer Sinha among others at CII webinar on renewable energy. 11:00 am: Prime Minister to inaugurate and lay the foundation stone of multiple development projects in Varanasi. 11:00 am: Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India Whole Time Member Mukulita Vijayawargiya at ASSOCHAM webinar on India’s bankruptcy code and valuation. 12:30 pm: Mercedes-Benz India Vice President Santosh Iyer at the virtual launch of new luxury vehicles. 3:00 pm: Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das, Financial Services Secretary Debasish Panda and other bank heads at The Economic Times Financial Inclusion summit. 3:20 pm: Reserve Bank of India former Deputy Governors Usha Thorat and N.S. Vishwanathan, SPJIMR Associate Professor - Finance Ananth Narayan, J P Morgan Chase Bank India Managing Director P.D. Singh at IMC Banking & Finance conference. 4:00 pm: GST Council Joint Secretary S.K. Rahman at TIOL webinar. 6:30 pm: Fifteenth Finance Commission Chairman N.K. Singh, Former Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian, NITI Aayog former Vice Chairman Arvind Panagariya at India Policy Forum. INDIA TOP NEWS India bans Mastercard from issuing new cards in data storage row The Reserve Bank of India on Wednesday indefinitely barred Mastercard from issuing new debit or credit cards to domestic customers for violating data storage rules, dealing a blow to the U.S. -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Annual Report 2011-12 Towards Global Thought Leadership in Banking and Finance ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 1 Annual Report 2011-12 // As a large, fast growing economy, there is increasing global interest in India.... The integration of Indian financial markets into the global system and the introduction of new financial products require better risk management and financial engineering skills. It also casts new burdens on regulatory institutions. Enhancing the skills of personnel involved in the financial sector is, therefore, important…. In view of the rapidly changing environment, and given the growing strength of the Indian financial sector, there is a strong need for an institution that can act as a centre for policy research on areas relating to banking and finance. I am sure that in the near future, the Centre would grow into a global hub for banking and finance.// Manmohan Singh Prime Minister of India 2 Annual Report 2011-12 ver the last four years since the Lehman event, from the Reserve Bank of India we have been attending a number of international meetings – G-20, FSB, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision – of which India is a member. What struck me most of all about these meetings is that the agenda somewhat overtakes emerging economy concerns. Repeatedly OI found that we could not meaningfully engage in these meetings because there was nothing on the agenda relevant to India or to emerging economies in general. It is not as if, as emerging economies, we have no issues that deserve global deliberation. But we have not been able to raise them effectively because there is not enough research happening in emerging economies to concretise issues and concerns relevant to us. -

IPD 20 Pages

About CAFRAL The Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning (CAFRAL) has been set up by Reserve Bank of India in the backdrop of India's evolving role in the global economy, in the financial services sector and its position in various international fora, to develop into a global hub for research and learning in banking and finance. CAFRAL started functioning under its first Director, former Deputy Governor of Reserve Bank of India, Usha Thorat, in January 2011. CAFRAL's research focuses on areas of interest to central banks and regulators, more specifically financial sector regulation and supervision, risk measurement and management, financial markets, financial stability and financial inclusion. Its learning activities target the senior management in central banks, regulators, financial institutions and other stake holders, including government officials, in the financial sector. Its learning activities include seminars, conferences, round tables, workshops, apart from longer duration programs. CAFRAL's events provide an independent platform for academics, researchers and practitioners to explore issues in banking and finance so as to develop suitable policies and strategies. In carrying forward its objectives, CAFRAL collaborates with other institutions, both academic and non-academic. The Governor, Reserve Bank of India is the Chairman of the Governing Council of CAFRAL. About IPD The Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD) works to broaden dialogue and explore trade-offs in development policy by bringing the best ideas in development to policymakers facing globalization's complex challenges and opportunities. IPD strives to contribute to a more equitably governed world by democratizing the production and use of knowledge. Founded in July 2000 by Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, the IPD stimulates a heterodox policy dialogue on major issues in international development.