NARRATIVES OF CONFLICT

IN

AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY IN INDIA

by

JUHI HUDA

B.A., University of Pune, India, 2007 M.A., University of Pune, India, 2009 M.A., University of Nevada Reno, 2013

A thesis submitted to the

Faculty of the Graduate School of the

University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Environmental Studies Program

2019

This dissertation entitled:

Narratives of Conflict in Agricultural Biotechnology Policy in India written by Juhi Huda has been approved for the Environmental Studies Program

Committee Chair:

_________________________________________

Dr. Deserai Anderson Crow, Ph.D.

Committee Members:

_________________________________________

Dr. Sharon Collinge, Ph.D.

_________________________________________

Dr. Peter Newton, Ph.D.

_________________________________________

Dr. Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ph.D.

_________________________________________

Dr. Christopher M. Weible, Ph.D.

Date:

The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above-mentioned discipline.

IRB protocol # 16-0414

ii

ABSTRACT

Huda, Juhi (Ph.D., Environmental Studies)

Narratives of Conflict in Agricultural Biotechnology Policy in India

Thesis directed by Associate Professor Deserai Anderson Crow

The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) focuses attention on narratives in policy debates and their empirical analysis. While NPF has become an important and accepted approach to studying the policy process, the majority of research applies it to policy and linguistic contexts of the United States, which limits its generalizability and responsiveness to cultural specificity. In this dissertation, I primarily endeavor to push the NPF forward by refining its concepts and testing its transportability by applying it to the policy subsystem of agricultural biotechnology policy in India. Secondly, I examine how the information contained in these narratives pertaining to policy problems, solutions, science, ethics, risk, and other factors is used strategically in the contentious issue of agricultural biotechnology. I use a mixed method approach drawing on quantitative and qualitative content analysis and qualitative interview data to empirically analyze how stakeholders use policy narratives to interact and advocate for policy change.

Using the case study of commercialization of a genetically modified crop, Bt eggplant, I examine media coverage from leading English newspapers in India to explore the strategic use of narrative variables. Findings indicate that policy narratives do not always contain a full suite of narrative components and yet may be among the most common messages received by the public and political actors emphasizing a need to further refine the definition of policy narratives and consider which narratives are important from empirical and audience reception perspectives. I examine the NPF assumption that narratives have generalizable narrative elements irrespective of variation in linguistic context and test its transportability. Findings lend support to its

iii transportability outside the English language and indicate variation in use of narrative elements across languages. Examining setting and plot, I explore further into the policy issue of agricultural biotechnology and focus on the evidence in support of claims about risks and benefits and explore moral notions of risk. Findings indicate that stakeholders use different sources of evidence and proponents de-emphasize risks and exclusively highlight benefits while opponents invoke multi-dimensional risk; and risk perceptions of stakeholders are influenced by moral notions of risk. In sum, the findings inform both the theoretical study of NPF and communication practices of stakeholders.

iv

To kismet

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A number of people made this dissertation possible, contributed to my professional development, and provided invaluable support. I can never adequately thank all of them and I apologize for inadvertently leaving anyone out.

To my dissertation chair – Dr. Deserai Crow: Deserai, thank you for taking a chance on me. Without your unwavering support and constant guidance, I am certain I would not have made it this far. Your mentorship is invaluable, and I could not have asked for a more thoughtful, caring, driven, and organized advisor. Your meticulous planning and organization made the dissertation process smoother than I could have ever imagined and helped turn dissertation chapters into published journal articles. Thank you for the research opportunities, for your advocacy on my behalf, and for your words of advice and encouragement at each and every turn. Thank you!

To my committee members – Drs. Elizabeth Shanahan, Christopher Weible, Peter Newton, and Sharon Collinge: Liz, thank you for your generous feedback on each of my papers from this dissertation. Your thoughtful advice and your desire to advance the NPF forward pushed this dissertation further than I’d imagined it could go. Thank you for always asking the hard questions. Chris, thank you for your feedback on my papers. Liz and Chris, your thoughtful and detailed suggestions helped transform my ideas into publishable manuscripts. Pete, thank you for the insightful conversations on food and agriculture, for your enthusiasm about my project, and for your support. Sharon, thank you for teaching ENVS 5000 in Fall 2014. It was the module on genetic engineering that triggered my journey into agricultural biotechnology. Your enthusiasm for the topic encouraged me to explore it more.

To my research group – Elizabeth Koebele, Lydia Lawhon, John Berggren, Adrianne Kroepsch, and Rebecca Schild: Collaborating with you all helped me gain so much research and publication experience. Thank you!

To all those I met and who helped me in the field in India – Thank you to the interview participants who shared their valuable time and insight. Thank you to those at Dainik Jagran, especially Mr. Radhe Shyam and Mr. Vijay Singh, who made the Hindi media data collection possible. And thank you to friends, Nisha Garud, Ranjeeth Rane, Preeti Virkar, Hrishi Chandanpurkar, who leveraged contacts to help me connect with interview participants.

To friends, colleagues, faculty, and staff in the Environmental Studies Program (ENVS) and in the Program for Writing and Rhetoric (PWR) – Members of the graduate committee at ENVS, thank you for funding so much of my research. It would not have been possible without your generous support. Thank you also for the teaching opportunities. Dr. Max Boykoff, thank you for the opportunity to collaborate. Penny Bates and Jean Lindahl, thank you for making the administrative processes so much smoother. Thank you to PWR - Dr. Steve Lamos, thank you for your excellent guidance on pedagogical practices, thank you to Drs. Steve Lamos and Linda Nicita for the teaching opportunities, and to Melynda Slaughter for helping to navigate the administrative process at PWR.

vi

To mentors – I wouldn’t have started on this path to my Ph.D. if Dr. Scott Slovic and Dr. Derek Kauneckis (then at University of Nevada Reno) had not guided me in pursuing my own passion and interests. Thank you for your mentorship and guidance. I am also grateful to Dr. Chandrani Chatterjee and (late) Dr. Aniket Jaaware for their early mentorship at the University of Pune. They triggered my journey halfway across the planet.

To family – Ammi and Abba, thank you for not holding me back. To my brother, Yusuf, and sister-in-law, Renita, thank you for your love and support even if you, at times, had no idea what I was doing with my life. To Nani, possibly the strongest woman I’ve known. Wish you’d lived to see your granddaughter on this day. I miss you everyday. To Badi Khala and Choti Khala, thank you for your strength, encouragement, and unconditional love. To Aai, Aba, and the Chandanpurkar family, thank you for your love and acceptance. To the two felines in my life, Pan aka Pantalaimon and BoCo aka BoulderColorado. You’ve brought me so much joy and peace. Thank you for all the cuddles.

And finally, thank you to Hrishi. Without you, I know I wouldn’t be here. Thank you for believing in me, even when I didn’t.

This research has been financially supported by the Graduate School, the Center to Advance Research and Teaching in the Social Sciences (CARTSS), and the Environmental Studies Program at University of Colorado Boulder.

vii

“Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer; they feed energy back and forth and amplify it. They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it.”

- Ursula K. Le Guin, Telling is Listening, The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the

Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (Shambhala Publications, 2004)

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION................................................................................................ 1

STRUCTURE OF THE DISSERTATION ............................................................................................................................6 REFERENCES ...............................................................................................................................................................7

CHAPTER 2: NARRATIVES OF CONFLICT IN AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY IN INDIA: THEORY, CASE STUDY, RESEARCH GOALS, AND METHODS .......................................................................................................... 8

THEORETICAL ORIENTATION ......................................................................................................................................9 RESEARCH DESIGN: CASE STUDY AND METHODOLOGY...........................................................................................13 RESEARCH GOALS AND FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................18 METHODS: DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS........................................................................................................20 REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................................................23

CHAPTER 3: AN EXAMINATION OF POLICY NARRATIVES IN AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY IN INDIA ............................................................................... 27

NPF AND PUBLIC POLICY SCHOLARSHIP ..................................................................................................................28 NPF AND POLICY NARRATIVES IN THE MEDIA .........................................................................................................30 BROADENING THE NPF: APPLICATIONS IN NON-U.S. AND OTHER POLICY CONTEXTS ............................................34 AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY—THE CASE OF BT EGGPLANT IN INDIA................................................35 RESEARCH METHODS ...............................................................................................................................................37 RESEARCH FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................................40 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS...................................................................................................................52 REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................................................56

CHAPTER 4: POLICY NARRATIVES ACROSS TWO LANGUAGES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING THE NARRATIVE POLICY FRAMEWORK............ 60

NARRATIVE POLICY FRAMEWORK, NARRATIVE ELEMENTS, AND THE MEDIA .........................................................63 WHY STUDY POLICY NARRATIVES ACROSS LANGUAGES?.......................................................................................67 BACKGROUND INFORMATION: BT EGGPLANT COMMERCIALIZATION PROCESS .......................................................70 METHODS..................................................................................................................................................................72 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND OPERATIONALIZATION.................................................................................................76 EXPECTATIONS, RESEARCH FINDINGS, AND DISCUSSION .........................................................................................77 CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................................................................97 REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................................................100

CHAPTER 5: SOURCES OF EVIDENCE FOR RISKS AND BENEFITS IN AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY IN INDIA: EXAMINING SETTING AND PLOT IN POLICY NARRATIVES .............................................................................. 106

NPF AND PUBLIC POLICY SCHOLARSHIP:...............................................................................................................108 SOURCES OF EVIDENCE AND PERCEPTION OF RISKS AND BENEFITS .......................................................................108 EVIDENCE FOR RISKS AND BENEFITS IN AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY...........................................................113

AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY IN INDIA: EVIDENCE OF RISKS AND BENEFITS IN BT EGGPLANT......................116

METHODS................................................................................................................................................................119 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................................................125 CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS.........................................................................................137 REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................................................140

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION ................................................................................................ 146

SUMMARY OF MAJOR FINDINGS .............................................................................................................................146 A BRIEF REFLECTION ON THE PROCESS ..................................................................................................................150 AREAS OF FUTURE RESEARCH AND CLOSING THOUGHTS.......................................................................................151

ix

REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................................................154

BIBLIOGRAPHY..................................................................................................................... 155 APPENDICES........................................................................................................................... 166

MEDIA CODEBOOK............................................................................................................................................166 INTERVIEW PROTOCOL....................................................................................................................................178

x

LIST OF TABLES

CHAPTER 3

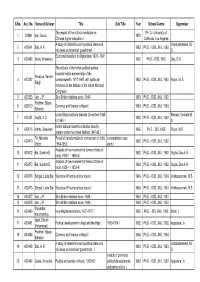

Table 3. 1: Search Terms, Newspapers, and Article Counts ........................................................ 38 Table 3. 2: Categories of Problem Definitions in Times of India and Hindustan Time s.............. 42 Table 3. 3: Policy Problems and Presence of Evidence, Solutions, and Risk/Benefit Information in Times of India and Hindustan Times........................................................................................ 43 Table 3. 4: Problem Definitions Used by the Losing, Winning, and Incomplete Narratives....... 44 Table 3. 5: Narrative Variables across Losing, Winning, and Incomplete Policy Narratives...... 46 Table 3. 6: Presence of Character Types in Times of India and Hindustan Times....................... 48 Table 3. 7: Use of Characters across Losing, Winning, and Incomplete Policy Narratives......... 50 Table 3. 8: Narrativity Index for Losing, Winning, and Incomplete narratives; and for Times of India and Hindustan Time s........................................................................................................... 52

CHAPTER 4

Table 4. 1. Newspapers, Search Terms, and Article Counts......................................................... 74 Table 4. 2. Intercoder Reliability Scores ...................................................................................... 75 Table 4. 3. Narrative Elements Across Hindi and English Media................................................ 78 Table 4. 4. Appearance of Policy Problems over Time across Hindi and English Media............ 80 Table 4. 5. Appearance of Policy Solutions over Time across Hindi and English Media............ 84 Table 4. 6. Focus of Policy Solutions over time........................................................................... 86 Table 4. 7. Appearance of Characters over Time across Hindi and English Media..................... 88 Table 4. 8. Use of Evidence over Time across Hindi and English Media.................................... 95 Table 4. 9. Types of Evidence provided over time....................................................................... 96

CHAPTER 5

Table 5. 1. Expectations.............................................................................................................. 125 Table 5. 2. Evidence in Media Data (n=99)................................................................................ 126 Table 5. 3. Interview Data – Sources of Evidence...................................................................... 128 Table 5. 4. Risks and Benefits in Media Data (n=99)................................................................. 131 Table 5. 5. Interview Data: Perceptions of Risks........................................................................ 132 Table 5. 6. Interview Data: Perceptions of Benefits................................................................... 133 Table 5. 7. Interview Data – Moral Notions of Risk .................................................................. 136

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

CHAPTER 3

Figure 3. 1: Coverage of Types of Narratives............................................................................... 39 Figure 3. 2: Focus of Coverage over Time in Times of India and Hindustan Time s.................... 42

CHAPTER 4

Figure 4. 1. Issue Coverage on Similar Events across Hindi (n=19) and English Media (n=52). 75 Figure 4. 2. Focus of Problem Definitions over time ................................................................... 82 Figure 4. 3. Character Appearance over Time.............................................................................. 89 Figure 4. 4. Heroes and Villains Across Hindi and English Media.............................................. 91 Figure 4. 5. Appearance of Heroes over Time Across Hindi and English Media ........................ 93

xii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

The green revolution in the 1960s led to an increase in agricultural production globally but half a century later the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO)’s 2015 report entitled “The State of Food Insecurity in the World” estimated that about 795 million people are chronically undernourished (UNFAO, 2015). With the projected growth in population, overall food demand is expected to increase by more than 50% and animal-based foods demand by nearly 70% by 2050 (Searchinger, Waite, Hanson, & Ranganathan, 2018). With world population growing rapidly, the number of food insecure people is expected to increase. While the green revolution of the sixties was characterized by an increased use of fertilizers, pesticides, and intensive irrigation techniques that enabled high-yielding varieties of crops, it also led to widespread soil pollution and massive depletion of groundwater reserves (Rodell, Velicogna, & Famiglietti, 2009). There has been an increase in calls for a second green revolution to increase agricultural production.

Governing bodies are seeking ways to meet the growing demand for food sustainably.

Various solutions include increasing agricultural productivity, shifting dietary patterns, increasing cropping efficiency. Although food policies are focused on a general goal of fulfilling basic human needs, some proposals such as agricultural biotechnology are entangled in politically polarizing and contentious debates. Genetically modified (GM) crops such as glyphosate-resistant crops and Bacillus thuringensis (Bt) crops protect the crops from herbicides and pests respectively. This may potentially result in increased yields and reduced use of pesticides (Kishore, Padgette, & Fraley, 1992; Qaim & Zilberman, 2003). However, agricultural biotechnology has received a mixed reception globally.

1

As per a 2017 report, the United States continues to lead in the adoption of GM crops with ten crops planted in 2017, while Canada planted six. The European Union continues to lead the Western Hemisphere in rejection of agricultural biotechnology with a few exceptions in Spain and Portugal. Commercialization of GM crops in Africa (thirteen countries) and Latin America (eleven countries) has increased. Leading biotech countries in Asia and the Pacific region include India, followed by Pakistan, China, Australia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Bangladesh contributing to 10% of the global biotech crops. Lack of government approval has blocked several GM crops such as Golden Rice, Bt eggplant, and drought tolerant and insect resistant maize in different regions. Bt eggplant, commercialized in Bangladesh is banned in neighboring India. Regulatory approval for drought tolerant and insect resistant maize, a public-private collaboration of four countries in sub-Saharan Africa remains stalled, while Brazil approved a virus-resistant bean in 2011 but the technology has not reached farmers (ISAAA, 2017).

Deployment of biotechnology has introduced risk-related concerns, which has often culminated in struggles amongst stakeholders to influence policy outcomes. In the politics of