Economic Considerations of Biosafety and Biotechnology Regulations in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download/Isaaa-Brief-53-2017.Pdf

NARRATIVES OF CONFLICT IN AGRICULTURAL BIOTECHNOLOGY POLICY IN INDIA by JUHI HUDA B.A., University of Pune, India, 2007 M.A., University of Pune, India, 2009 M.A., University of Nevada Reno, 2013 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Environmental Studies Program 2019 This dissertation entitled: Narratives of Conflict in Agricultural Biotechnology Policy in India written by Juhi Huda has been approved for the Environmental Studies Program Committee Chair: _________________________________________ Dr. Deserai Anderson Crow, Ph.D. Committee Members: _________________________________________ Dr. Sharon Collinge, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Dr. Peter Newton, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Dr. Christopher M. Weible, Ph.D. Date: The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above-mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 16-0414 ii ABSTRACT Huda, Juhi (Ph.D., Environmental Studies) Narratives of Conflict in Agricultural Biotechnology Policy in India Thesis directed by Associate Professor Deserai Anderson Crow The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) focuses attention on narratives in policy debates and their empirical analysis. While NPF has become an important and accepted approach to studying the policy process, the majority of research applies it to policy and linguistic contexts of the United States, which limits its generalizability and responsiveness to cultural specificity. In this dissertation, I primarily endeavor to push the NPF forward by refining its concepts and testing its transportability by applying it to the policy subsystem of agricultural biotechnology policy in India. -

Indian Contribution to Science

196 Indian Contributions to Science INDIANINDIAN CONTRIBUTIONSCONTRIBUTIONS TOTO SCIENCESCIENCE Compiled By Vijnana Bharati Indian Contributions To Science Indian Contributions To Science Compiled by Vijnana Bharati All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to: Vijnana Bharati C-486, Defence Colony, New Delhi- 110 024 Second Edition 2017 Contents Preface ..................................................................................................vii Vidyarthi Vigyan Manthan (VVM Edition – VI) 2017-18 ........... ix Acknowledgement .................................................................................xi 1. India’s Contribution to Science and Technology .................1 (From Ancient to Modern) 2. Astronomy in India ...................................................................9 3. Chemistry in India: A Survey ................................................20 4. The Historical Evolution of....................................................30 Medicinal Tradition in Ancient India 5. Plant and Animal Science in Ancient India .........................39 6. Mathematics in India ..............................................................46 7. Metallurgy in India .................................................................58 8. Indian Traditional -

Dynamics of Biotechnology Research and Industry in India: Statistics, Sachin Chaturvedi Perspectives and Key Policy Issues

OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers 2005/06 Dynamics of Biotechnology Research and Industry in India: Statistics, Sachin Chaturvedi Perspectives and Key Policy Issues https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/873577115356 Unclassified DSTI/DOC(2005)6 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 31-May-2005 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY Unclassified DSTI/DOC(2005)6 DYNAMICS OF BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH AND INDUSTRY IN INDIA: STATISTICS, PERSPECTIVES AND KEY POLICY ISSUES STI WORKING PAPER 2005/6 Statistical Analysis of Science, Technology and Industry Sachin Chaturvedi text only English JT00185361 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/DOC(2005)6 STI Working Paper Series The Working Paper series of the OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies prepared by staff in the Directorate or by outside consultants working on OECD projects. The papers included in the series cover a broad range of issues, of both a technical and policy-analytical nature, in the areas of work of the DSTI. The Working Papers are generally available only in their original language – English or French – with a summary in the other. Comments on the papers are invited, and should be sent to the Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry, OECD, 2 rue André-Pascal, 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France. The opinions expressed in these papers are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries. -

Biotechnology Industry in India

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 01 , 2020 BIOTECHNOLOGY INDUSTRY IN INDIA Dr. R.JAGANNATHAN1 , Dr. P. RAVICHANDRAN2 1,2Assistant professor in commerce, Rajeswari Vedhachalam Govt Arts College, Chengalpattu. Abstract: India's biotechnology industry has been developing towards new statures related to the recent economic outburst. The nation can possibly reform bio drug and medical services areas. The Indian Biotechnology Industry is one of the fastest growing industries in India. Data has to be collected from multiple sources of evidence to understand the importance and overview of the biotechnology industry, in addition to books, journals, various websites, and newspapers. This article presents a brief overview of the current biotechnology industry in India, Global Biotechnology Market Size, and Regional Segment Analysis of the Biotechnology Market, Current Scenario in Biotechnology industry in India and marketing challenges. Keywords: Biotechnology, BIRAC, Bio-Agri, Bio-industrial, Bioinformatics, Bio-pharma, Bio- services. Introduction: India is among the first countries to set up a specialized agency i.e. department of biotechnology under the Ministry of Science and Technology for the development of research and human resources in the biotechnology sector in 1986.1The biotechnology sector of India is highly innovative and is on a strong growth trajectory. The sector, with its immense growth potential, will continue to play a significant role as an innovative manufacturing hub. The sector is one of the most significant sectors in enhancing India's global profile as well as contributing to the growth of the economy.2And Biotechnology has vast potential to grow in India. Indian biotech sector stands 3rd in the Asia pacific region in terms of number of companies, about 40% of these are in the Biopharma segment and the rest are in Agri Biotech, Bioinformatics, industrial Biotechnology and Bioservices. -

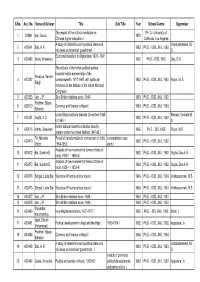

Withdrawn Records of Theses.Xlsx

S.No. Acc. No. Name of Scholar Title Sub Title Year School/Centre Supervisor The impact of the cultural revolution on Ph. D.- University of 1 23599 Kan, David. 1970. Chinese higher education / California, Los Angeles. A study of Hebert Hoover's political ideas and Vanakataramani, M. 2 A19941 Sita, A. K. 1963. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1963. his views on American government / S. Economic transition in Afghanistan 1929 - 1961 3 A20496 Guha, Amalendu. 1962. Ph.D. - ISIS, 1962. Dey, S. K. / The attitude of the Indian political parties towards India's membership of the Pavadya, Balram 4 A23322 commonwealth, 1917-1957, with particular 1962. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1962. Rajan, M. S. Singh. reference to the attitude of the Indian National Congress / 5 A23323 Jain, J.P. Sino-British relations since, 1949 / 1963. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1963. Pradhan, Bijaya 6 A26010 Currency and finance in Nepal / 1964. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1964. Bahadur. United States attitude towards China from 1945 Ramani, Venkata M. 7 A26251 Gupta, D.C. 1963. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1963. to 1950 / S. India's attitude towards collective security 8 A29016 Mehta, Swadesh. 1965. Ph.D. - SIS, 1965. Rajan, M.S. system under the United Nations 1947-62 / Fic, Miroslav Peaceful transformation to communism in India a comparative case 9 A30470 1962. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1962. Victor. 1954-1952 : study / Analysis of the movement of terms of trade of 10 A30472 Bai, Sumitra D. 1962. Ph.D. - ISIS, JNU, 1962. Gupta, Das A. K. India, 1930-1 - 1953-4 / Analysis of the movement of terms of trade of 11 A30473 Bai, Sumitra D. -

Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering

GLOBAL ISSUES BIOTECHNOLOGY AND GENETIC ENGINEERING GLOBAL ISSUES BIOTECHNOLOGY AND GENETIC ENGINEERING Kathy Wilson Peacock Foreword by Charles Hagedorn, Ph.D. Professor, Environmental Microbiology, Virginia Tech GLOBAL ISSUES: BioTECHNologY AND GENETIC ENgiNeeRING Copyright © 2010 by Infobase Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Peacock, Kathy Wilson. Biotechnology and genetic engineering / Kathy Wilson Peacock; foreword by Charles Hagedorn. p.; cm. — (Global issues) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8160-7784-7 (alk. paper) 1. Biotechnology—Popular works. 2. Genetic engineering—Popular works. I. Title. II. Series: Global issues (Facts on File, Inc.) [DNLM: 1. Biotechnology. 2. Genetic Engineering. 3. Organisms, Genetically Modified—genetics. QU 450 P352b 2010] TP248.215.P43 2010 660.6—dc22 2009025794 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Illustrations by Dale Williams Composition by Mary Susan Ryan-Flynn Cover printed by Art Print, Taylor, Pa. Book printed and bound by Maple Press, York, Pa. -

Biotechnology in India Year 2014 New Delhi/India

Name of the Report: Biotechnology in India Year 2014 New Delhi/India 1. Summary of the Sector Biotechno log y is steadily emerging high potential growth sector Ind ia an d has the potential to take the coun try into the next big leagu e of i nterna l an d interna tiona l investmen t. The coun try ha s don e well in pha rmaceutical sector an d this ha s he lpe d evolve the biotech sector over the last decade . According to Investment and Technology Promotion (ITP) report, biotechnology market is estimated to reach USD 11. 6 b illion by 2017 with an estimated growth rate (CAGR) of 22 percent. The key growth drivers of the US $ 4.3 billion industry include robust domestic demand, growth in contract services; focus on research and development (R & D) initiatives and strong governm ent support for the sector. The existing biotechnology network in the country comprises nearly three hundred national laboratories and a number of universities. Included amongst top 12 biotech destinations in the world, India has immense potential to emerg e as a global key player. Majority of biotech companies operate in the bio -pharma sector which accounts for approximately 64 percent . Bengaluru is the biotech capital of India with 60 percent companies. Source: www.ibef.org Ritu Arora _______________________________________________________________________________________________ __ 2. Government Policy India aims to spend USD 3.7 billion on biotechnology in its 12 th Five Year Plan. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is allowed up to 100 percent through the automatic route for manufacturers of drugs and p harmaceuticals in the sector . -

India's National Innovation System: Key Elements and Corporate Perspectives

The East-West Center is an education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and understanding among the peoples and nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center contributes to a peace- ful, prosperous, and just Asia Pacific community by serving as a vigorous hub for cooperative research, education, and dialogue on critical issues of common concern to the Asia Pacific region and the United States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corpora- tions, and the governments of the region. East-West Center Working Papers are circulated for comment and to inform interested colleagues about work in progress at the Center. For more information about the Center or to order publications, contact: Publication Sales Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Telephone: 808.944.7145 Facsimile: 808.944.7376 Email: [email protected] Website: www.EastWestCenter.org EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS Economics Series No. 96, August 2008 India's National Innovation System: Key Elements and Corporate Perspectives Cornelius Herstatt, Rajnish Tiwari, Dieter Ernst, and Stephan Buse Cornelius Herstatt is Director and Professor at the Institute for Technology and Innovation Management, Hamburg University of Technology. He is also a founding partner at the European Institute for Technology and Innovation Management. He has published extensively on innovation and technology management. Rajnish Tiwari is Research Associate at the Institute of Technology and Innovation Management at Hamburg University of Technology in Germany. He was awarded the “Market and Customer Orientation 2006” prize by the Vodafone Foundation for Research. -

Annual Report 2019-20 English.Pmd

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Department of Biotechnology Ministry of Science & Technology Government of India DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 2 DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY Contents 1. OVERVIEW 5 2. BUILDING CAPACITIES 23 - HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT, TRAINING AND WORKSHOPS 24 - RESEARCH RESOURCES, SERVICE FACILITIES AND PLATFORMS 44 - BIO-TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE CLUSTERS 48 3. RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT, DEMONSTRATION AND TRANSLATION ACTIVITIES 53 - AGRICULTURE AND ALLIED AREAS 54 - BIOENERGY, BIORESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT 66 - HEALTHCARE AND MEDICAL BIOTECHNOLOGY 82 - KNOWLEDGE GENERATION, DISCOVERY RESEARCH, NEW TOOLS 111 AND TECHNOLOGIES 4. PROMOTING ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INDUSTRIAL GROWTH 126 - STARTUP INDIA 127 - MAKE IN INDIA 128 - BIODESIGN PROGRAMME 129 - BIOTECHNOLOGY PARKS & INCUBATORS 133 5. BUILDING INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS AND PARTNERSHIPS 137 6. SPECIAL PROGRAMMES 144 - PROGRAMMES FOR SOCIETAL RELEVANCE – RURAL, SC/ST 145 POPULATION AND WOMEN 7. PROMOTING BIOTECHNOLOGY IN NORTH EASTERN REGION 156 8. AUTONOMOUS INSTITUTIONS AND PUBLIC SECTOR UNDERTAKINGS 163 9. REGULATION, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND LEGISLATIONS 204 10. ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 207 ABBREVIATIONS 212 DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY 3 01 OVERVIEW ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 The Department of Biotechnology (DBT) set up more than there is a need for creating right kind of manpower with three decades ago under the aegis of Ministry of Science and requisite skill set. Hence, impetus has been on supporting Technology has been instrumental in creating a strong various -

India: the Uneven Innovator Kirsten Bound

India: The uneven innovator Kirsten Bound The Atlas of Ideas: Mapping the new geography of science About Demos Demos is one of the UK’s most influential think tanks. Our research focuses on five areas: cities, culture, identity, public services and science. We analyse social and political change, which we connect to innovation and learning in organisations. Our partners include policy-makers, companies, public service providers and social entrepreneurs. Our international network – which extends across Europe, Scandinavia, Australia, Brazil, India and China – provides a global perspective and enables us to work across borders. As an independent voice, we can create debates that lead to real change. We use the media, public events, workshops and publications to communicate our ideas. All our publications can be downloaded free from www.demos.co.uk Kirsten Bound is a researcher at Demos, where her research centres on international aspects of science, innovation and governance. Kirsten has authored reports including one for the Electoral Commission on the European parliamentary elections and co-authored a report with Tom Bentley for the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise on how Sweden can reinvent the rules of political economy. Kirsten’s global network includes collaborative work with the Finnish innovation agency, SITRA. Her publications include Mapping Local Governance for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, and Community Participation: Who benefits? published in 2006 by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Forthcoming publications include an international -

Healthcare Biotechnology in India

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 2005, 20 (1) 201-207 HEALTHCARE BIOTECHNOLOGY IN INDIA L.M.SRIVASTAVA Department of Biochemistry, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Rajinder Nagar. New De/hL The production and commercialization of the first world class research in biotechnology and two public therapeutic recombinant human protein humulin sector industries (Table 2). Besides these (human insulin) in 1982 by Eli Lilly marked the dawn of establishments, DBT also awards a large number of a new era of unprecedented economic opportunities - research grants to investigators working in different the era of biotechnology hetherto unrecognized. The areas of biotechnology and fellowships to work in impact of biotechnology revolution was so strong in Indian and foreign laboratodes. Public investment in the U.S. that by late eighties all the 15 to 20 top biotechnology has resulted in more than 5000 multibillion pharmaceutical companies were into it and research, publications and a huge reservoir of trained several entrepreneurial new biotechnology firms were manpower and 46 technologies which have been established (Gibbons, 1984). For the most part they transferred to industries for further development and have been founded since 1976 - the same year the commercialization (DBT Annual Report 2002-2003). A U.S. firm Genentech was founded. The peak year for few of these technologies have been launched and a the formation of biotechnology start-ups in the U.S. fewer have been commercialized (Table 3). However, was 1982; in the UK. it was 1987. Start-ups in Japan most of the commercialized products are not visible were only few probably that the Japanese environment on the market and sales are insignificant. -

Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science

ISSN (Online) : 2456-6632 Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science An International Journal Volume 1 | Issue 1 Agriculture and Environmental Science Academy www.aesacademy.org Scan to view it on the web Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science (An International Research Journal) (Abbreviation: Arch. Agr. Environ. Sci.) Aims & Objectives: The journal is an official publication of Agriculture and Environmental Science Academy. Its goal is to publish scientific research views in the field of Agriculture Sciences, and Environmental Sciences; and any other related field to promote speedy propagation of quality research information. Periodicity: Four issues in a year (March, June, September and December) Editor-in-Chief Dr. Vinod Kumar Department of Zoology and Environmental Science Gurukula Kangri University, Haridwar (Uttarakhand), INDIA E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Associate Editors Dr. Sachin Srivastva, Dehradun, India Dr. Temin Payum, Pesighat, India Advisory Board Prof. Bharat Raj Subba, Biratnagar, Nepal Prof. Dr. Barbara Sawicka, Lublin Poland Prof. A.K. Chopra, Haridwar, India Prof. N.C. Gupta, Delhi, India Prof. Kavita Shah, Varanasi, India Prof. S.K. Singh, Varanasi, India Dr. T. Ramanathan, Parangipettai, India Er. Omkar Singh, Roorkee, India Editorial Board Dr. Adarsh Kumar Pandey, Malaysia Dr. M.F. Alam, Jazan, Saudi Arabia Dr. S.K. Paul, Mymensingh, Bangladesh Dr. Mritunjay K. Pandey, Kanpur, India Dr. Vineet V. Tyagi, Katra, Jammu, India Dr. Naveen Kumar Arora, Lucknow, India Dr. Kuldeep