Rhododendron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province

Selecting Plants for Pollinators A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers, and Gardeners In the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province Including the states of: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia And parts of: Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina, NAPPC South Carolina, Tennessee Table of CONTENTS Why Support Pollinators? 4 Getting Started 5 Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest 6 Meet the Pollinators 8 Plant Traits 10 Developing Plantings 12 Far ms 13 Public Lands 14 Home Landscapes 15 Bloom Periods 16 Plants That Attract Pollinators 18 Habitat Hints 20 This is one of several guides for Check list 22 different regions in the United States. We welcome your feedback to assist us in making the future Resources and Feedback 23 guides useful. Please contact us at [email protected] Cover: silver spotted skipper courtesy www.dangphoto.net 2 Selecting Plants for Pollinators Selecting Plants for Pollinators A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers, and Gardeners In the Ecological Region of the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province Including the states of: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia And parts of: Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee a nappc and Pollinator Partnership™ Publication This guide was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the C.S. Fund, the Plant Conservation Alliance, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management with oversight by the Pollinator Partnership™ (www.pollinator.org), in support of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC–www.nappc.org). Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest – Coniferous Forest – Meadow Province 3 Why support pollinators? In theIr 1996 book, the Forgotten PollInators, Buchmann and Nabhan estimated that animal pollinators are needed for the reproduction “ Farming feeds of 90% of flowering plants and one third of human food crops. -

States Symbols State/ Union Territories Motto Song Animal / Aquatic

States Symbols State/ Animal / Foundation Butterfly / Motto Song Bird Fish Flower Fruit Tree Union territories Aquatic Animal day Reptile Maa Telugu Rose-ringed Snakehead Blackbuck Common Mango సతవ జయే Thalliki parakeet Murrel Neem Andhra Pradesh (Antilope jasmine (Mangifera indica) 1 November Satyameva Jayate (To Our Mother (Coracias (Channa (Azadirachta indica) cervicapra) (Jasminum officinale) (Truth alone triumphs) Telugu) benghalensis) striata) सयमेव जयते Mithun Hornbill Hollong ( Dipterocarpus Arunachal Pradesh (Rhynchostylis retusa) 20 February Satyameva Jayate (Bos frontalis) (Buceros bicornis) macrocarpus) (Truth alone triumphs) Satyameva O Mur Apunar Desh Indian rhinoceros White-winged duck Foxtail orchid Hollong (Dipterocarpus Assam सयमेव जयते 2 December Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) (O My Endearing Country) (Rhinoceros unicornis) (Asarcornis scutulata) (Rhynchostylis retusa) macrocarpus) Mere Bharat Ke House Sparrow Kachnar Mango Bihar Kanth Haar Gaur (Mithun) Peepal tree (Ficus religiosa) 22 March (Passer domesticus) (Phanera variegata) (Mangifera indica) (The Garland of My India) Arpa Pairi Ke Dhar Satyameva Wild buffalo Hill myna Rhynchostylis Chhattisgarh सयमेव जयते (The Streams of Arpa Sal (Shorea robusta) 1 November (Bubalus bubalis) (Gracula religiosa) gigantea Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) and Pairi) सव भाण पयतु मा किच Coconut palm Cocos दुःखमानुयात् Ruby Throated Grey mullet/Shevtto Jasmine nucifera (State heritage tree)/ Goa Sarve bhadrāṇi paśyantu mā Gaur (Bos gaurus) Yellow Bulbul in Konkani 30 May (Plumeria rubra) -

Case Study of Rhododendron

Utsala A case study on Uses of Rhododendron of Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale area, Eastern Nepal. PREPARED BY: UTSALA SHRESTHA GRADUATE IN AGRICULTURE (C ONSERVATION ECOLOGY ) DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE IAAS, RAMPUR , CHITWAN FUNDED BY: NATIONAL RHODODENDRON CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE (NORM), BASANTPUR -4, TERHATHUM , NEPAL MARCH 2009 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2. HISTORY OF RHODODENDRON ................................................................................ 3 3. DISTRIBUTION OF RHODODENDRON ...................................................................... 3 4. RHODODENDRONS OF NEPAL ................................................................................... 4 5. SCOPE AND IMPORTANCE OF STUDY ..................................................................... 5 6. OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................... 6 7. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................ 6 8. STUDY AREA ................................................................................................................. 7 9. IMPORTANCE OF RHODODENDRON IN TMJ .......................................................... 9 -

The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel Wallich

C O N N E C T I N G P E O P L E , P L A C E S , A N D I D E A S : S T O R Y B Y S T O R Y J ULY 2 0 1 3 ABOUT WRR CONTRIBUTORS MISSION SPONSORSHIP MEDIA KIT CONTACT DONATE Search Join our mailing list and receive Email Print More WRR Monthly. Wild River Consulting ESSAY-The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel & Wallich : Publishing Click below to make a tax- deductible contribution. Religious Identity in the Age of Enlightenment where Your literary b y J u d i t h M . T a y l o r , J u l e s J a n i c k success is our bottom line. PEOPLE "By the time the Interv iews wise woman has found a bridge, Columns the crazy woman has crossed the Blogs water." PLACES Princeton The United States The World Open Borders Lorenzo Da Ponte Nathaniel Wallich ANATOLIAN IDEAS DAYS & NIGHTS Being Jewish in a Christian world has always been fraught with difficulties. The oppression of the published by Art, Photography and Wild River Books Architecture Jews in Europe for most of the last two millennia was sanctioned by law and without redress. Valued less than cattle, herded into small enclosed districts, restricted from owning land or entering any Health, Culture and Food profession, and subject to random violence and expulsion at any time, the majority of Jews lived a History , Religion and Reserve Your harsh life.1 The Nazis used this ancient technique of de-humanization and humiliation before they hit Philosophy Wild River Ad on the idea of expunging the Jews altogether. -

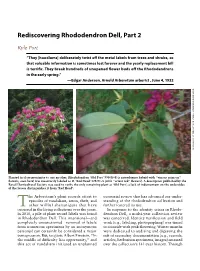

Rediscovering Rhododendron Dell, Part 2

Rediscovering Rhododendron Dell, Part 2 Kyle Port “They [hoodlums] deliberately twist off the metal labels from trees and shrubs, so that valuable information is sometimes lost forever and the yearly replacement bill is terrific. They break hundreds of unopened flower buds off the Rhododendrons in the early spring.” —Edgar Anderson, Arnold Arboretum arborist , June 4, 1932 ated C DI N I E S erwi H T SS O E UNL R HO T U A E H T Y B S E G A M I ALL Planted in close proximity to one another, Rhododendron ‘Old Port’ 990-56-B (a catawbiense hybrid with “vinous crimson” flowers, seen here) was incorrectly labeled as R. ‘Red Head’ 329-91-A (with “orient red” flowers). A description published by the Royal Horticultural Society was used to verify the only remaining plant as ‘Old Port’; a lack of indumentum on the undersides of the leaves distinguishes it from ‘Red Head’. he Arboretum’s plant records attest to curatorial review that has advanced our under- episodes of vandalism, arson, theft, and standing of the rhododendron collection and Tother willful shenanigans that have further fostered its use. occurred in the living collections over the years. In response to the identity crises in Rhodo- In 2010, a pile of plant record labels was found dendron Dell, a multi-year collection review in Rhododendron Dell. This intentional—and was conceived. Identity verification and field completely unsanctioned—removal of labels work (e.g., labeling, photographing) was timed from numerous specimens by an anonymous to coincide with peak flowering. -

Structural Adaptations in Overwintering Leaves of Thermonastic and Nonthermonastic Rhododendron Species Xiang Wang Iowa State University

Genetics, Development and Cell Biology Genetics, Development and Cell Biology Publications 11-2008 Structural Adaptations in Overwintering Leaves of Thermonastic and Nonthermonastic Rhododendron Species Xiang Wang Iowa State University Rajeev Arora Iowa State University, [email protected] Harry T. Horner Iowa State University, [email protected] Stephen L. Krebs David G. Leach Station of the Holden Arboretum Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/gdcb_las_pubs Part of the Horticulture Commons, Other Plant Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Plant Breeding and Genetics Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ gdcb_las_pubs/47. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Genetics, Development and Cell Biology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genetics, Development and Cell Biology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Structural Adaptations in Overwintering Leaves of Thermonastic and Nonthermonastic Rhododendron Species Abstract Evergreen rhododendrons (Rhododendron L.) are important woody landscape plants in many temperate zones. During winters, leaves of these plants frequently are exposed to a combination of cold temperatures, high radiation, and reduced photosynthetic activity, conditions that render them vulnerable to photooxidative damage. In addition, these plants are shallow-rooted and thus susceptible to leaf desiccation when soils are frozen. In this study, the potential adaptive significance of leaf morphology and anatomy in two contrasting Rhododendron species was investigated. -

Host Range of a Select Isolate of the Eri Coid Mycorrhizal Fungus

PROPAGATION & TISSUE CULTURE HORTSCIENCE 38(6):1163–1166. 2003. Berta and Bonfante-Fasolo, 1983; Bradley et al., 1981; Leake and Read, 1989). Other studies have attempted to evaluate the host Host Range of a Select Isolate of range of ericoid fungi, but have inoculated with unidentified ericoid fungal isolates, described, the Eri coid Mycorrhizal Fungus for example as, “dark, slow-growing cultures” (Pearson and Read, 1973b; Reed, 1987). Hymenoscyphus ericae To date there have been no studies that investigate the host range of a select isolate Nicole R. Gorman1 and Mark C. Starrett2 of the ericoid endophyte H. ericae. Therefore, Department of Plant and Soil Science, University of Vermont, Burlington, the objective of this study was to evaluate the VT 05405-0082 host range using select species within the Eri- caceae by inoculating with a specific iso late Additional index words. Ericaceae, Calluna, Enkianthus, Gaultheria, Kalmia, Leucothoe, of H. ericae. Oxydendrum, Pieris, Rhodo den dron, Vaccinium Materials and Methods Abstract. Studies were conducted to ex am ine the host range of a select isolate of the ericoid mycorrhizal fungus Hymenoscyphus ericae (Read) Korf and Kernan [American Type Seed of 15 ericaceous species was ob tained Culture Collection (ATCC) #32985]. Host status was tested for 15 ericaceous species, in- from commercial seed suppliers [Sheffield·s cluding: Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull, Enkianthus campanulatus (Miq.) Nichols, Gaultheria Seed Co. (Lock, N.Y.) and F.W. Schumacher procumbens L., Kalmia latifolia L., Leucothoe fontanesiana Sleum., Oxydendrum arbo- Co. (Sandwich, Mass.)]. Seed was cleaned and reum (L.) DC., Pieris flo ri bun da (Pursh) Benth. -

Observations on Food Habits of Asiatic Black Bear in Kedarnath Wildlifesanctuary, India: Preliminaryevidence on Their Role in Seed Germination and Dispersal

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS Observations on food habits of Asiatic black bear in Kedarnath WildlifeSanctuary, India: preliminaryevidence on their role in seed germination and dispersal S. Sathyakumar1'3 and S. Viswanath2'4 food and feeding habits of the Malayan sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) in Central Borneo, Indonesia, 1WildlifeInstitute of India,P.O. Box 18, indicated that this species could be an importantseed Chandrabani,Dehradun 248 001, India dispenser depending upon the species consumed, 2Instituteof Forest Genetics and Tree Breeding, numberof seeds ingested, and the deposition site. Forest Campus, Coimbatore641002 India Asiatic black bears are well known seed predators. that acorns Key words: Asiatic black bear, food habits, germination Manjrekar(1989) reported (Quercus robur) and walnuts were crushed tests, seed dispersal,seed germination,seed predator, (Juglans regia) totally by black bears while on them, Symplocos theifolia, Ursus thibetanus feeding thereby hindering Ursus14(1):99-103 (2003) dispersal. Black bears were also reported to feed on seeds fallen on the ground,and signs of regenerationof species, walnut in particular,were reportedto be low. We presentobservations on the food and feeding habits In India, the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus) of Asiatic black bearand observationson germinationof occurs in forested habitats of the GreaterHimalaya at bear food plants in Kedarath Wildlife Sanctuary(WS), 1,200-3,000 m elevation (Sathyakumar2001). Informa- Western Himalayaduring 1989-92. tion on the feeding and movement patternsof Asiatic black bear in India is limited to 2 short studies (Manjrekar1989, Saberwal 1989) and some observa- Study area tions by Schaller (1969), all in Dachigam National Park Kedarath WS (975 km2) is located in Uttaranchal, (NP) in Jammu and Kashmir,India. -

Bioactive Compounds, Health Benefits and Utilization of Rhododendron: A

Kumar et al. Agric & Food Secur (2019) 8:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-019-0251-3 Agriculture & Food Security REVIEW Open Access Bioactive compounds, health benefts and utilization of Rhododendron: a comprehensive review Vikas Kumar* , Sheenam Suri, Rasane Prasad, Yogesh Gat, Chesi Sangma, Heena Jakhu and Manjri Sharma Abstract The Rhododendron distributed throughout the world is a small evergreen tree with deep red or pale pink fowers, belongs to the family Ericaceae and is known for its spectacular fowers. The species is widely distributed between the latitudes 80°N and 20°S with high socioeconomic reverence and has been designated as the national fower of Nepal and state fower of Himachal Pradesh (India). In addition to its immense horticultural importance, it is commonly used as an ornamental plant for gardens, plantations in the streets or vessels for its aesthetic value. Because of its numerous phytochemical potential, it is being utilized as a traditional remedy for diferent diseases. Flowers of this plant are tra- ditionally utilized by the people residing in the mountainous region to make pickle, juice, jam, syrup, honey, squash, etc., and to treat various ailments like diarrhea, headache, infammation, bacterial and fungal infections. The present review highlights the medicinal, nutritional and potential properties of Rhododendron by making value-added prod- ucts to improve the livelihood for sustainable development of the rural tribal population with more job opportunities. Keywords: Rhododendron, Ericaceae, Ornamental, Infammation, Nutritive value Background in some regions of Bhutan. Te aesthetic beauty of the Nature provides us an access to a diverse group of plants fully blossomed fowers in the fowering season attracts with numerous usages including decoration, medici- the attention of the visitors [2]. -

Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (UEAP)

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 47229-001 July 2016 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (UEAP) Package: Construction of FRP huts in disaster affected district of Kumaon (District Bageshwar) Uttarakhand Submitted by Project implementation Unit –UEAP, Tourism (Kumaon), Nainital This initial environment examination report has been submitted to ADB by Project implementation Unit – UEAP, Tourism (Kumaon), Nainital and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB Project Number: 3055-IND April 2016 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project Submitted by Project implementation Unit, UEAP, Kumaon Mandal Vikas Nigam limited, Nainital 1 This report has been submitted to ADB by the Project implementation Unit, UEAP, Kumaon Mandal Vikas Nigam, Nainital and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Asian Development Bank 2 Initial Environmental Examination April 2016 INDIA: CONSTRUCTION OF FRP HUTS IN DISASTER AFFECTED DISTRICT OF KUMAON (DISTRICT BAGESHWAR) UTTARAKHAND Prepared by State Disaster Management Authority, Government of India, for the Asian Development Bank. -

Habitat and Feeding Ecology of Alpine Musk Deer (Moschus Chrysogaster) in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand, India

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279062545 Habitat and feeding ecology of alpine musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster) in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand, India Article in Animal Production Science · January 2015 DOI: 10.1071/AN141028 CITATIONS READS 0 41 2 authors: Zarreen Syed Orus Ilyas Wildlife Institute of India Aligarh Muslim University 6 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS 21 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation and Development Initiative View project All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Orus Ilyas letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 26 September 2016 CSIRO PUBLISHING Animal Production Science http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AN141028 Habitat preference and feeding ecology of alpine musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster) in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand, India Zarreen Syed A and Orus Ilyas B,C AWildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, 248001, India. BDepartment of Wildlife Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, 202002, India. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The alpine musk deer, Moschus chrysogaster, a small member of family Moschidae, is a primitive deer threatened due to poaching and habitat loss, and therefore classified as Endangered by IUCN and also listed in Appendix I of CITES. Although the species is legally protected in India under Wildlife Protection Act 1972, conservation of the species requires better understanding of its distribution and resource-use pattern; therefore, a study on its feeding and habitat ecology was conducted from February 2011 to February 2014, at Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary.