Rheology of PIM Feedstocks SPECIAL FEATURE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Inertia and End Effects in Rheometer Flows

FLUID INERTIA AND END EFFECTS IN RHEOMETER FLOWS by JASON PETER HUGHES B.Sc. (Hons) A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Mathematics and Statistics Faculty of Technology University of Plymouth April 1998 REFERENCE ONLY ItorriNe. 9oo365d39i Data 2 h SEP 1998 Class No.- Corrtl.No. 90 0365439 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors Dr. J.M. Davies, Prof. T.E.R. Jones and Dr. K. Golden for their continued support and guidance throughout the course of my studies. I also gratefully acknowledge the receipt of a H.E.F.C.E research studentship during the period of my research. AUTHORS DECLARATION At no time during the registration for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has the author been registered for any other University award. This study was financed with the aid of a H.E.F.C.E studentship and carried out in collaboration with T.A. Instruments Ltd. Publications: 1. J.P. Hughes, T.E.R Jones, J.M. Davies, *End effects in concentric cylinder rheometry', Proc. 12"^ Int. Congress on Rheology, (1996) 391. 2. J.P. Hughes, J.M. Davies, T.E.R. Jones, ^Concentric cylinder end effects and fluid inertia effects in controlled stress rheometry, Part I: Numerical simulation', accepted for publication in J.N.N.F.M. Signed ...^.^Ms>3.\^^. Date Ik.lp.^.m FLUH) INERTIA AND END EFFECTS IN RHEOMETER FLOWS Jason Peter Hughes Abstract This thesis is concerned with the characterisation of the flow behaviour of inelastic and viscoelastic fluids in steady shear and oscillatory shear flows on commercially available rheometers. -

On Exact Solution of Unsteady MHD Flow of a Viscous Fluid in An

Rana et al. Boundary Value Problems 2014, 2014:146 http://www.boundaryvalueproblems.com/content/2014/1/146 R E S E A R C H Open Access On exact solution of unsteady MHD flow of a viscous fluid in an orthogonal rheometer Muhammad Afzal Rana1, Sadia Siddiqa2* and Saima Noor3 *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 2Department of Mathematics, COMSATS Institute of Information This paper studies the unsteady MHD flow of a viscous fluid in which each point of Technology, Attock, Pakistan the parallel planes are subject to the non-torsional oscillations in their own planes. Full list of author information is The streamlines at any given time are concentric circles. Exact solutions are obtained available at the end of the article and the loci of the centres of these concentric circles are discussed. It is shown that the motion so obtained gives three infinite sets of exact solutions in the geometry of an orthogonal rheometer in which the above non-torsional oscillations are superposed on the disks. These solutions reduce to a single unique solution when symmetric solutions are looked for. Some interesting special cases are also obtained from these solutions. Keywords: viscous fluid; MHD flow; orthogonal rheometer; eccentric rotation; exact solutions 1 Introduction Berker [] has defined the ‘pseudo plane motions’ of the first kind that: if the streamlines in a plane flow are contained in parallel planes but the velocity components are dependent on the coordinate normal to the planes. Berker [] has obtained a class of exact solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations belonging to the above type of flows. -

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 1: Introduction E. J. Hinch Non-Newtonian fluids occur commonly in our world. These fluids, such as toothpaste, saliva, oils, mud and lava, exhibit a number of behaviors that are different from Newtonian fluids and have a number of additional material properties. In general, these differences arise because the fluid has a microstructure that influences the flow. In section 2, we will present a collection of some of the interesting phenomena arising from flow nonlinearities, the inhibition of stretching, elastic effects and normal stresses. In section 3 we will discuss a variety of devices for measuring material properties, a process known as rheometry. 1 Fluid Mechanical Preliminaries The equations of motion for an incompressible fluid of unit density are (for details and derivation see any text on fluid mechanics, e.g. [1]) @u + (u · r) u = r · S + F (1) @t r · u = 0 (2) where u is the velocity, S is the total stress tensor and F are the body forces. It is customary to divide the total stress into an isotropic part and a deviatoric part as in S = −pI + σ (3) where tr σ = 0. These equations are closed only if we can relate the deviatoric stress to the velocity field (the pressure field satisfies the incompressibility condition). It is common to look for local models where the stress depends only on the local gradients of the flow: σ = σ (E) where E is the rate of strain tensor 1 E = ru + ruT ; (4) 2 the symmetric part of the the velocity gradient tensor. The trace-free requirement on σ and the physical requirement of symmetry σ = σT means that there are only 5 independent components of the deviatoric stress: 3 shear stresses (the off-diagonal elements) and 2 normal stress differences (the diagonal elements constrained to sum to 0). -

Rheometry SLIT RHEOMETER

Rheometry SLIT RHEOMETER Figure 1: The Slit Rheometer. L > W h. ∆P Shear Stress σ(y) = y (8-30) L −∆P h Wall Shear Stress σ = −σ(y = h/2) = (8-31) w L 2 NEWTONIAN CASE 6Q Wall Shear Rateγ ˙ = −γ˙ (y = h/2) = (8-32) w h2w σ −∆P h3w Viscosity η = w = (8-33) γ˙ w L 12Q 1 Rheometry SLIT RHEOMETER NON-NEWTONIAN CASE Correction for the real wall shear rate is analogous to the Rabinowitch correction. 6Q 2 + β Wall Shear Rateγ ˙ = (8-34a) w h2w 3 d [log(6Q/h2w)] β = (8-34b) d [log(σw)] σ −∆P h3w Apparent Viscosity η = w = γ˙ w L 4Q(2 + β) NORMAL STRESS DIFFERENCE The normal stress difference N1 can be determined from the exit pressure Pe. dPe N1(γ ˙ w) = Pe + σw (8-45) dσw d(log Pe) N1(γ ˙ w) = Pe 1 + (8-46) d(log σw) These relations were calculated assuming straight parallel streamlines right up to the exit of the die. This assumption is not found to be valid in either experiment or computer simulation. 2 Rheometry SLIT RHEOMETER NORMAL STRESS DIFFERENCE dPe N1(γ ˙ w) = Pe + σw (8-45) dσw d(log Pe) N1(γ ˙ w) = Pe 1 + (8-46) d(log σw) Figure 2: Determination of the Exit Pressure. 3 Rheometry SLIT RHEOMETER NORMAL STRESS DIFFERENCE Figure 3: Comparison of First Normal Stress Difference Values for LDPE from Slit Rheometer Exit Pressure (filled symbols) and Cone&Plate (open symbols). The poor agreement indicates that the more work is needed in order to use exit pressures to measure normal stress differences. -

The Design and Analysis of a Micro Squeeze Flow Rheometer

The Design and Analysis of a Micro Squeeze Flow Rheometer By David Cheneler A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Mechanical Engineering College of Engineering and Physical Sciences The University of Birmingham September 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis describes the analysis and design of a micro squeeze flow rheometer. The need to analyse the rheology of complex liquids occurs regularly in industry and during research. However, frequently the amount of fluid available is too small, precluding the use of conventional rheometers. Conventional rheometers also tend to have the disadvantage of being too massive, preventing them from operating effectively at high frequencies. The investigation carried out in this thesis has revealed that current microrheometry techniques also have their own disadvantages. The proposed design is a stand-alone device capable of measuring the dynamic properties of nanolitre volumes of viscoelastic fluid at frequencies up to the kHz range, an order of magnitude greater than conventional rheometers. The device uses a single piezoelectric component to both actuate and sense its own position. -

One-Dimensional Differential Newtonian Analysis for Applications in Saliva Rheology

One-dimensional Differential Newtonian Analysis for Applications in Saliva Rheology by Louise Lu McCarroll A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Mechanical Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor William W Schultz, Co-Chair Professor Michael J Solomon, Co-Chair Professor Joseph Bull Dr. Joseph T Murray, Veterans Affairs Hospital Professor Alan S Wineman Louise Lu McCarroll [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1471-0655 © Louise Lu McCarroll 2017 For my parents, Yin and Lin Lin ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I think the best phrase that describes this experience for me is \it takes a village" or in my case it should be \it takes a whole metropolitan area and then some." But I'll stick with the \village" analogy for now. The chief villagers I'd like to thank are my advisors, Professor William Schultz and Professor Michael Solomon, for their seemingly unlimited supply of patience with me, especially when I was feeling like the village idiot. Thank you for your guidance these past few years, for teaching me to be resourceful, to a construct logical argument and perform novel analyses, for propping me up when my spirits were low, and last but not least, for being so approachable. I have really enjoyed working on this project with you both. Bill - I am still trying to learn how to \embrace chaos." Mike - I appreciate all the structure you have imposed on this process. I'd also like to extend my gratitude to my committee members, Professor Alan Wineman, Professor Joseph Bull, and Dr. -

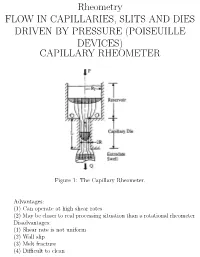

Rheometry FLOW in CAPILLARIES, SLITS and DIES DRIVEN by PRESSURE (POISEUILLE DEVICES) CAPILLARY RHEOMETER

Rheometry FLOW IN CAPILLARIES, SLITS AND DIES DRIVEN BY PRESSURE (POISEUILLE DEVICES) CAPILLARY RHEOMETER Figure 1: The Capillary Rheometer. Advantages: (1) Can operate at high shear rates (2) May be closer to real processing situation than a rotational rheometer Disadvantages: (1) Shear rate is not uniform (2) Wall slip (3) Melt fracture (4) Difficult to clean 1 Rheometry CAPILLARY RHEOMETER NEWTONIAN CASE The velocity profile from the Navier-Stokes Equations is: 2Q r 2 v(r) = 1 − (8-9) πR2 R dv Shear Rateγ ˙ = (8-6) dr −4Qr γ˙ (r) = πR4 r γ˙ (r) = γ˙ (R) (8-8) R Wall Shear Rateγ ˙ w ≡ −γ˙ (R) (8-11) 4Q γ˙ = (8-12) w πR3 The shear stress from the Navier-Stokes Equations is: r dP σ(r) = − (8-2) 2 dz R dP σ(R) = − (8-3) 2 dz r σ(r) = σ(R) (8-4) R R dP Wall Shear Stress σ ≡ σ(R) = − (8-5) w 2 dz σ σ (−dP/dz)πR4 Viscosity η = = w = (8-14) γ˙ γ˙ w 8Q 2 Rheometry CAPILLARY RHEOMETER NON-NEWTONIAN CASE 4 σw (−dP/dz)πR Apparent Viscosity ηA = = (8-15) γ˙ A 8Q Since the shear rate varies across the radius of the capillary, a non- Newtonian fluid will have an effective viscosity that depends on radial posi- tion. Figure 2: Dependence of Real Shear Stress σ, Apparent Shear Rateγ ˙ a, and Real Shear Rateγ ˙ on Radial Position for a Non-Newtonian Fluid Flowing in a Capillary. 3 Rheometry CAPILLARY RHEOMETER NON-NEWTONIAN CASE THE RABINOWITCH CORRECTION There is a unique relation between the wall shear stress and the apparent wall shear rate. -

Dynisco Viscosensor Online Rheometer

Dynisco ViscoSensor Online Rheometer Experience the benefits of online rheology measurement Polymer manufacturers need to create new materials and deliver high quality to meet ever changing end-use requirements. Precise testing and analysis is mandatory to ensure quality and to stay competitive. Rely on Dynisco’s solutions to gain a window into your process and speed up the development, production, quality testing and analysis of polymers. Material Analysis Dynisco™ analyzers, including melt flow indexers, and rheometers, are recognized for testing the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of polymers. Offering worldwide support and innovative instruments that span the complete life cycle of a polymer, Dynisco’s material analysis solutions range from the analysis of a polymer in the laboratory, to online quality control in production, to processing small quantities of special polymers or composites. Scrap Reduction No matter what stage of the polymer’s life cycle, eliminating waste and keeping production levels at peak capacity are crucial to ensuring profitability in today’s highly competitive environment. Our goal is to provide objective measurements and high quality testing to improve and speed the development and production of polymers. Sustainability Sustainability is more than just protecting the environment. We want to lead the way to the future and empower you with sensors, controls, and analytical instruments that offer maximum control, reduce downtime, minimize scrap, and promote environmental consciousness. The ability to feed used plastic into the supply chain to manufacture new materials, with less costs and without compromises in material specifications, is the goal and has to be realized through objective measurements and analysis. -

Understanding Yield Stress Measurements

WHITEPAPER Understanding Yield Stress Measurements The yield stress characteristic is a property associated with numerous types of complex fluids - whereby the material does not flow unless the applied stress RHEOLOGY AND VISCOSITY exceeds a certain value. This is evident in everyday tasks such as squeezing toothpaste from a tube or dispensing ketchup from a bottle, but is important across a whole range of industries and applications. The determination of a yield stress as a true material constant can be difficult as the measured value can be very much dependent on the measurement technique employed and the conditions of the test, of which there are many. Consequently, there is no universal method for determining yield stress and there exist a number of approaches, which find favour across different industries and establishments. This White Paper discusses the various approaches available to measure yield stress, and aspects of the practical measurement set-up and test parameters that need to be considered to obtain relevant, robust and reliable yield stress data using a rotational rheometer. Introduction Many complex fluids, such as network forming polymers, surfactant mesophases, emulsions etc do not flow until the applied stress exceeds a certain critical value, known as the yield stress. Materials exhibiting this behavior are said to be exhibiting yield flow behavior. The yield stress is therefore defined as the stress that must be applied to the sample before it starts to flow. Below the yield stress the sample will deform elastically (like stretching a spring), above the yield stress the sample will flow like a liquid [1]. Most fluids exhibiting a yield stress can be thought of as having a structural skeleton extending throughout the entire volume of the system. -

Exploring the Viscoelastic Properties of Cheese Using a Rheometer

Exploring the Viscoelastic Properties of Cheese Using a Rheometer Keywords: Rheology, Cheese, Viscoelastic Properties, Strain Sweep, Frequency Sweep, Temperature Ramp RH098 ABSTRACT EXPERIMENTAL Cheese has unique viscoelastic behavior. Its viscoelastic A commercial cheddar cheese was used as an example cheese properties are sensitive to its storage and use conditions. At sample for all of the rheological testing. The viscoelastic properties room temperature, cheese behaves like a soft solid where G’ is of the cheddar cheese were examined using a TA Instruments greater than G”. As temperature is increased, cheese undergoes DHR-3 rheometer with the Peltier temperature control system. a solid-to-liquid transition. Above this transition temperature, A 25-mm sandblasted upper and lower parallel plate geometry cheese flows like a viscous liquid which makes it possible to was selected for the purpose of reducing wall slip during the coat and cover the surface of food like pizza. In this paper, the measurements. viscoelastic properties of cheddar cheese are analyzed using a TA Instruments Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (DHR). Dynamic strain sweep, frequency sweep, and temperature ramp test methods are described for quantitative analyses of the viscoelastic properties of cheeses. INTRODUCTION In the cheese production industry, not only is sensory perception important, but the physical properties, such as flow behavior and elasticity, are also important to cheese production and processing. Cheese is made from milk. The major components in cheese are casein protein, fat, and an aqueous component [1-2]. At ambient temperatures, cheese behaves like a viscoelastic gel. This is because casein at this temperature is solid and exists as micelles in the viscous matrix. -

Rheometer Quick Start Guide

Rheometers – Quick Start Guide Polymer Facilities - MRL @ UCSB Rachel Behrens ([email protected]) Reservations: Reserve with FBS, login to FBS to access instrument. Record instrument time on Log sheet. Safety: The rheometer contains a high-torque motor. Turning on the motor while in dynamic mode causes the motor to snap to dynamic zero position at a high velocity. This can cause severe damage to the transducer and/or personal injury. To avoid damaging yourself and the transducer: 1. Never turn on the motor while a sample is loaded. 2. Keep hands clear of the motor. Turning on the Instrument: 1. Turn on lab air on the east hood to the red mark on the gauge on Rheometer I (or past if both rheometers are being used) 2. Turn on switch to rheometer on the back of the instrument 3. Turn on water bath and set temperature (for Rheo I) 4. On the computer, open TA Orchestrator Choosing your parameters: • Plate geometry and size o Plates (8mm, 25mm, 50mm) o Cone (25mm, 50mm) o Couette • Test mode and Motor mode: steady or dynamic o Dynamic Mode (sinusoidal) o Steady Mode (linear) Choosing a Geometry Size: 1. Assess the ‘Viscosity’ of your sample. 2. Lower viscosity larger plate diameter a. Low viscosity (milk)- 50 mm geometry b. Medium viscosity (honey)- 25 mm geometry c. High viscosity (caramel)- 8 mm geometry 3. Examine data in terms of absolute instrument variables [torque/speed/displacement] and modify geometry choice to move into optimum working range. 4. You may need to reconsider your selection after the first run. -

The Society of Rheology 79Th Annual Meeting (October 2007) Program and Abstracts

THE SOCIETY OF RHEOLOGY 79TH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS Hilton Salt Lake City Center Salt Lake City, Utah October 7 - 11, 2007 Program Committee: Mataz Alcoutlabi Matt Liberatore University of Utah Colorado School of Mines Patrick Anderson James Oberhauser Eindhoven University of Technology University of Virginia Ralph Colby Jai Pathak Pennsylvania State University US Naval Research Lab John Dorgan Bob Prud’homme Colorado School of Mines Princeton University Pat Doyle Jonathan Rothstein Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Massachusetts Eric Furst Jay Schieber University of Delaware Illinois Institute of Technology Michael Graham (Co-Chair) Nina Shapley University of Wisconsin Columbia University Erik Hobbie Phil Sullivan National Institute of Standards & Technology Schlumberger Technology Corp Ravi P. Jagadeeshan Sachin Velankar Monash University University of Pittsburgh Rajesh Khare Henning Winter Texas Tech University University of Massachusetts Daniel Klingenberg (Co-Chair) University of Wisconsin Local Arrangements: Jules Magda Andy Kraynik University of Utah Sandia National Laboratories Abstract Book Editor and Webmaster: Albert Co, University of Maine Meeting Schedule Monday, October 8, 2007 Tuesday, October 9, 2007 Wednesday, October 10, 2007 Thursday, October 11, 2007 8:30 F. Waleffe (PL1) 8:30 J. F. Brady (PL2) 8:30 J. A. Lewis (PL3) 8:05 SC41 BE17 SM17 SG1 9:20 Coffee 9:20 Coffee 9:20 Coffee 8:30 SC42 BE18 SM18 SG2 9:45 SC1 FM1 MR1 PS1 9:45 FM14 MR14 PS14 9:45 SC27 BE4 SM3 BS5 8:55 EP1 BE19 SM19 SG3