Population Displacement Strategies in Civil Wars by Adam G. Lichtenheld

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

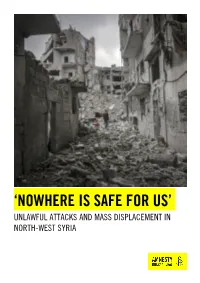

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

American University of Beirut Detection of Fake News in the Syrian

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT DETECTION OF FAKE NEWS IN THE SYRIAN WAR by ROAA AL FEEL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science to the Department of Computer Science of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at the American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon January 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to use this opportunity to express my gratitude to everyone who supported me throughout my masters study and through the process of research- ing and writing this thesis. I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Fa- tima Abu Salem for giving me the opportunity to be involved in this research project and her invaluable guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and im- mense knowledge throughout this research. I am also grateful to the members of my thesis committee for all of their guidance throughout this process; your discussion, ideas, and feedback have been absolutely invaluable. I would also like to thank my friends at AUB who have shared this experience with me for all the fun we have had in this journey. And last but by no means least, I am extremely grateful to my parents and brother for all the love, support, and constant encouragement they have provided me with throughout my years of study. This accomplishment would not have been possible without you all. Thank you. v An Abstract of the Thesis of Roaa Al Feel for Master of Science Major: Computer Science Title: Detection of Fake News in the Syrian War After almost eight years of conflict, the humanitarian situation in Syria con- tinues to deteriorate year after year. -

Sanctions Program: Syrien: Verordnung Vom 8. Juni 2012 Über Massnahmen Gegenüber Syrien (SR 946.231.172.7), Anhang 7 Origin: EU Sanctions: Art

Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research EAER State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO Bilateral Economic Relations Sanctions Modification of 02.10.2017 with entry into force on 03.10.2017 Sanctions program: Syrien: Verordnung vom 8. Juni 2012 über Massnahmen gegenüber Syrien (SR 946.231.172.7), Anhang 7 Origin: EU Sanctions: Art. 10 Abs. 1 (Finanzsanktionen) und Art. 17 Abs. 1 (Ein- und Durchreiseverbot) Sanctions program: Syrie: Ordonnance du 8 juin 2012 instituant des mesures à l’encontre de la Syrie (RS 946.231.172.7), annexe 7 Origin: EU Sanctions: art. 10, al. 1 (Sanctions financières) et art. 17, al. 1 (Interdiction de séjour et de transit) Sanctions program: Siria: Ordinanza dell'8 giugno 2012 che istituisce provvedimenti nei confronti della Siria (RS 946.231.172.7), allegato 7 Origin: EU Sanctions: art. 10 cpv. 1 (Sanzioni finanziarie) e art. 17 cpv. 1 (Divieto di entrata e di transito) Amended Individuals SSID: 200-36113 Name: Saji' Darwish Title: Major General DOB: 11 Jan 1957 Good quality a.k.a.: a) Saji (Sajee, Sjaa) b) Jamil c) Darwis Justification: a) Holds the rank of Major General, a senior officer and former Commander of the 22nd Division of the Syrian Arab Air Force, in post after May 20112011. Operates in the chemical weapons proliferation sector and is responsible for the violent repression against the civilian population: as a senior ranking officer of the Syrian Arab Air Force and Commander of the 22nd Division until April 2017 he holds responsibility for the use of chemical weapons by aircraft operating from airbases under the control of the 22nd Division, including the attack on Talmenes that the Joint Investigative Mechanism reported was conducted by Hama airfield-based regime helicopters. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL NOTICE GIVEN NO EARLIER THAN 7:00 PM EDT ON SATURDAY 9 JULY 2016 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “Torpedoed” by the West? By Adam Larson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, May 02, 2013 Theme: US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA Since the perplexing conflict in Syria first broke out two years ago, the Western powers’ assistance to the anti-government side has been consistent, but relatively indirect. The Americans and Europeans lay the mental, legal, diplomatic, and financial groundwork for regime change in Syria. Meanwhile, Arab/Muslim allies in Turkey and the Persian Gulf are left with the heavy lifting of directly supporting Syrian rebels, and getting weapons and supplementary fighters in place. The involvement of the United States in particular has been extremely lackluster, at least in comparison to its aggressive stance on a similar crisis in Libya not long ago. Hopes of securing major American and allied force, preferrably a Libya-style “no-fly zone,” always leaned most on U.S. president Obama’s announcement of December 3, 2012, that any use of chemical weapons (CW) by the Assad regime – or perhaps their simple transfer – will cross a “red line.” And that, he implied, would trigger direct U.S. intervention. This was followed by vague allegations by the Syrian opposition – on December 6, 8, and 23 – of government CW attacks. [1] Nothing changed, and the allegations stopped for a while. However, as the war entered its third year in mid-March, 2013, a slew of new allegations came flying in. This started with a March 19 attack on Khan Al-Assal, a contested western district of Aleppo, killing a reported 25-31 people. -

Vulnerable and Marginalized Groups Framework (Vmgf)

VULNERABLE AND MARGINALIZED GROUPS FRAMEWORK (VMGF) FOR THE UGANDA DIGITAL ACCELERATION PROGRAM [UDAP] FPIC with The Tepeth Community in Tapac FPIC with the Batwa Community in Bundibugyo MARCH 2021 Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK Action Parties Designation Signature Prepared Chris OPESEN & Derrick Social Scientist & Environmental KYATEREKERA Specialist Reviewed Flavia OPIO Business Analyst Approved Vivian DDAMBYA Director Technical Services DOCUMENT NUMBER: NITA-U/2021/PLN THE NATIONAL INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY, UGANDA (NITA-U) Palm Courts; Plot 7A Rotary Avenue (Former Lugogo Bypass). P.O. Box 33151, Kampala- Uganda Tel: +256-417-801041/2, Fax: +256-417-801050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nita.go.ug The Uganda Digital Acceleration Program [UDAP) Page iii Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS........................................................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Background................................................................................................................................................. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Complaint for of the Estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, Heir-At-Law and 28 U.S.C

Case 1:16-cv-01423 Document 1 Filed 07/09/16 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Case 1:16-cv-01423 Document 1 Filed 07/09/16 Page 2 of 33 Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Suheil Al-Hassan and the Syrian Army?

Suheil al-Hassan and the Syrian Army's Tiger Forces By Lucas Winter Journal Article | Jul 22 2016 - 9:50am Suheil al-Hassan and the Syrian Army’s Tiger Forces Lucas Winter Introduction This paper looks at the genesis, evolution and growth of the Syrian Army’s “Tiger Forces” and their leader Suheil al-Hassan. The paper shows how Hassan has played an important role since conflict began in 2011. It attributes his transformation from special forces commander to leader of military campaigns to an ability to harness the Syrian Army’s full infantry, artillery and airpower better than any other loyalist field commander. Given the Syrian Army’s manpower shortages, rampant corruption and rivalry-laden bureaucracy, this is no small feat. Al-Hassan has become a key symbol in the Syrian loyalist camp, able to project more combined arms power than anyone else in Syria. His success on the battlefield comes less from tactical or strategic insights than from his ability to thrive within the loyalist camp’s opaque and rivalry-laden bureaucracy. For this he has become a symbol to regime supporters, proof that the war can be won by working within the system. Suheil al-Hassan and the "Tiger Forces" Suheil al-Hassan (September 2014) The Syrian Arab Army’s (SyAA) answer to Erwin Rommel is a man named Suheil al-Hassan. Nicknamed “The Tiger” (al-Nimr), al-Hassan has emerged as the SyAA’s best-known commander in the current Syrian War. Since 2012 he and his “Tiger Forces” have achieved a string of battlefield victories.