Abstract Documenting Indigenous Tagbanua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 249.73 Kb

C. CASUALTIES Two (2) dead persons and twelve (12) injured persons were caused by the effects of TS Auring. DEAD (2) : NAME AGE ADDRESS REMARKS 1. Nicanor Soprefencia 44 Brgy. Culandanum, Due to drowning Bataraza, Palawan 2. Pedro V. Francisco 35 Brgy. Iraan, Rizal, Hit by coconut tree Palawaan INJURED (12) : NAME AGE ADDRESS REMARKS District 2, Poblacion Second degree burns 1. Orlan Aralar 9 Brookes Point, Palawan due to electrocution District 2, Poblacion 2. Francis A. Nohil 47 Electrocution Brookes Point, Palawan Hit by galvanized 3. Asrah Tan 10 Brookes Point, Palawan roof sheet Sofronio Epañola, 4. Evelyn Lagrosa 51 Palawan 5. Tiben Ludivida 32 Vehicular Accident 6. Cesar Cadlaon 13 Brookes Point, Palawan 7. Rominiel Mitsa 16 8. (5) unnamed passengers of a vehicular accident D. DAMAGED PROPERTIES A total of sixty-three (63) totally and 122 partially damaged houses were reported in Regions IV-B and IX Area Totally Partially REGION IX 6 Roxas and Katipunan, Dipolog City 6 REGION IV -B 57 122 Puerto Princesa, Palawan 2 1 Rizal, Palawan 55 121 TOTAL 63 122 E. STATUS OF LIFELINES 1. AFFECTED ROADS REGION IV-B As of 8:00 PM, 07 January 2013, the Palawan Circumferential Road (Pangaligan-Tagbita Section) in Rizal, Palawan is not passable to all types of vehicles due to fallen trees and debris as a result of a landslide. III. ACTIONS TAKEN EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE: 1. NATIONAL PREPAREDNESS MEASURES NDRRMC NDRRMC Operations Center is on Red Alert Status and has been continuously monitored and disseminated Weather Bulletins, -

Region Penro Cenro Province Municipality Barangay

REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT AREA IN HECTARES NAMEOF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION COMPONENT COMMODITY SPECIES YEAR ZONE TENURE RIVER BASIN NUMBER OF LOA WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Sihi Lone District 34.02 LGU-Sihi LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0001-0034 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Boac Tumagabok Lone District 8.04 LGU-Tumagabok LGU Agroforestry Timber and Fruit Trees Narra, Langka, Guyabano, and Rambutan 2011 Production 11-174001-0002-0008 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Agroforestry Fruit Trees Langka 2011 Production 11-174001-0003-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 12.01 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection Untenured 11-174001-0004-0012 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 7.04 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0005-0007 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 3.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0006-0003 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 1.05 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0007-0001 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.03 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0008-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Yook Lone District 30.02 LGU-Yook -

Botanical Observations from a Threatened Riverine Lowland Forest in Aborlan, Palawan, Philippines

van Beijnen and Jose: Endemic flora of Aborlan, Palawan Botanical observations from a threatened riverine lowland forest in Aborlan, Palawan, Philippines Jonah van Beijnen1,* and Edgar D. Jose2 1 Fins & Leaves, Oude Bennekomseweg 23, 6706 ER Wageningen, the Netherlands 2 Western Philippines University, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines *Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research provided a general overview of the vegetation structure of the Talakaigan watershed, Aborlan, Palawan, Philippines, with highlights on some ecological aspects of selected flora and intent of providing urgently needed data supporting existing conservation efforts in the area. Observations were carried during regular trekking activities in the watershed and surrounding areas from 2009 to 2016. Photographs were taken to facilitate species identification. Several noteworthy observations are presented, including a new locality for Begonia palawanensis, a short description of several new species of Begonia and notes on a large population of the Critically Endangered Orania paraguanensis, including details on the early life history of these palm. A large number of anthropogenic disturbances were observed in the area, including well-intended forestation and development efforts by the local and provincial government. Since the watershed does not hold any formal protective status, these disturbances pose a serious threat to the future existence of this unique watershed and some of the endemic species it contains. Our findings support the call to declare the entire watershed as an official protected area. Keywords: floral inventory, lowland rainforest, conservation, Southeast Asia, Begonia, Orania. INTRODUCTION Palawan is a large island province in the southwest of the Philippines, northeast of Borneo. Because of the island’s low population density and the fact that its forests contain relatively few valuable hardwood species, it has been spared from massive deforestation that has plagued the rest of the Philippines (Vitug 1993). -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population

2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population MARINDUQUE 227,828 BOAC (Capital) 52,892 Agot 502 Agumaymayan 525 Amoingon 1,346 Apitong 405 Balagasan 801 Balaring 501 Balimbing 1,489 Balogo 1,397 Bangbangalon 1,157 Bamban 443 Bantad 1,405 Bantay 1,389 Bayuti 220 Binunga 691 Boi 609 Boton 279 Buliasnin 1,281 Bunganay 1,811 Maligaya 707 Caganhao 978 Canat 621 Catubugan 649 Cawit 2,298 Daig 520 Daypay 329 Duyay 1,595 Ihatub 1,102 Isok II Pob. (Kalamias) 677 Hinapulan 672 Laylay 2,467 Lupac 1,608 Mahinhin 560 Mainit 854 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Malbog 479 Malusak (Pob.) 297 Mansiwat 390 Mataas Na Bayan (Pob.) 564 Maybo 961 Mercado (Pob.) 1,454 Murallon (Pob.) 488 Ogbac 433 Pawa 732 Pili 419 Poctoy 324 Poras 1,079 Puting Buhangin 477 Puyog 876 Sabong 176 San Miguel (Pob.) 217 Santol 1,580 Sawi 1,023 Tabi 1,388 Tabigue 895 Tagwak 361 Tambunan 577 Tampus (Pob.) 1,145 Tanza 1,521 Tugos 1,413 Tumagabok 370 Tumapon 129 Isok I (Pob.) 1,236 BUENAVISTA 23,111 Bagacay 1,150 Bagtingon 1,576 Bicas-bicas 759 Caigangan 2,341 Daykitin 2,770 Libas 2,148 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, -

The Mammals of Palawan Island, Philippines

PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON 117(3):271–302. 2004. The mammals of Palawan Island, Philippines Jacob A. Esselstyn, Peter Widmann, and Lawrence R. Heaney (JAE) Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, P.O. Box 45, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines (present address: Natural History Museum, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, KS 66045, U.S.A.) (PW) Katala Foundation, P.O. Box 390, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines; (LRH) Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605 U.S.A. Abstract.—The mammal fauna of Palawan Island, Philippines is here doc- umented to include 58 native species plus four non-native species, with native species in the families Soricidae (2 species), Tupaiidae (1), Pteropodidae (6), Emballonuridae (2), Megadermatidae (1), Rhinolophidae (8), Vespertilionidae (15), Molossidae (2), Cercopithecidae (1), Manidae (1), Sciuridae (4), Muridae (6), Hystricidae (1), Felidae (1), Mustelidae (2), Herpestidae (1), Viverridae (3), and Suidae (1). Eight of these species, all microchiropteran bats, are here reported from Palawan Island for the first time (Rhinolophus arcuatus, R. ma- crotis, Miniopterus australis, M. schreibersi, and M. tristis), and three (Rhin- olophus cf. borneensis, R. creaghi, and Murina cf. tubinaris) are also the first reports from the Philippine Islands. One species previously reported from Pa- lawan (Hipposideros bicolor)isremoved from the list of species based on re- identificaiton as H. ater, and one subspecies (Rhinolophus anderseni aequalis Allen 1922) is placed as a junior synonym of R. acuminatus. Thirteen species (22% of the total, and 54% of the 24 native non-flying species) are endemic to the Palawan faunal region; 12 of these are non-flying species most closely related to species on the Sunda Shelf of Southeast Asia, and only one, the only bat among them (Acerodon leucotis), is most closely related to a species en- demic to the oceanic portion of the Philippines. -

Lidar Surveys and Flood Mapping of Aborlan River

LiDAR Surveys and Flood Mapping of Aborlan River 1 Hazard Mapping of the Philippines Using LIDAR (Phil-LIDAR 1) 2 LiDAR Surveys and Flood Mapping of Aborlan River © University of the Philippines Diliman and University of the Philippines Los Baños 2017 Published by the UP Training Center for Applied Geodesy and Photogrammetry (TCAGP) College of Engineering University of the Philippines – Diliman Quezon City 1101 PHILIPPINES This research project is supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) as part of its Grant-in-Aid Program and is to be cited as: E.C. Paringit, E.R. Abucay, (Eds.). (2017), LiDAR Surveys and Flood Mapping Report of Aborlan River, in Enrico C. Paringit (Ed.), Flood Hazard Mapping of the Philippines using LIDAR. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Training Center for Applied Geodesy and Photogrammetry. 151pp The text of this information may be copied and distributed for research and educational purposes with proper acknowledgement. While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this publication, the UP TCAGP disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) and costs which might incur as a result of the materials in this publication being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. For questions/queries regarding this report, contact: Asst. Prof. Edwin R. Abucay Project Leader Phil-LiDAR 1 Program University of the Philippines, Los Banos Los Banos, Philippines 4031 [email protected] Enrico C. Paringit, Dr. Eng. Program Leader, PHIL-LiDAR 1 Program University of the Philippines Diliman Quezon City, Philippines 1101 E-mail: [email protected] National Library of the Philippines ISBN: 987-621-430-118-8 iI Hazard Mapping of the Philippines Using LIDAR (Phil-LIDAR 1) TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................. -

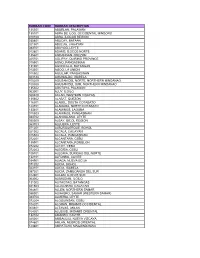

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

This Keyword List Contains Pacific Ocean (Excluding Great Barrier Reef)

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 3/2/2016 Pacific Ocean (without the Great Barrier Reef) This keyword list contains Pacific Ocean (excluding Great Barrier Reef) place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Pacific Ocean (without Great Barrier Reef)” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Cauit Reefs (13N123E0016) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Legaspi (13N123E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Manito Reef (13N123E0015) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Matalibong ( Bariis ) (13N123E0006) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Rapu Rapu Island (13N124E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Sto. Domingo (13N123E0002) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amalau Bay (14S170E0012) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amami-Gunto > Amami-Gunto (28N129E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > American Samoa (14S170W0000) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > Manu'a Islands (14S170W0038) OCEAN BASIN > -

In Southern Palawan, Philippines

REPORT Inventory, Distribution, and Conservation Action of the Critically Endangered Philippine Forest Turtle (Siebenrockiella = Panayenemys leytensis) in Southern Palawan, Philippines By Endangered Species International In partnership with Palawan State University October 2009 TABLE OF CONTENT 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................2 2.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................3 2.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING AND STUDY LOCATION .............................................................................................3 2.2. THE PHILIPPINE FOREST TURTLE (SIEBENROCKIELLA = PANAYENEMYS LEYTENSIS)..............................................5 3.0 OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT ....................................................................................................................6 4.0 METHODS .........................................................................................................................................................6 4.1 TRAININGS...........................................................................................................................................................6 4. 2 FIELD INTERVIEWS AND QUESTIONNAIRES ..........................................................................................................8 4.3 FIELD SURVEYS ...................................................................................................................................................9 -

The Emerging Oil Palm Agro-Industry in Palawan, the Philippines: SEI Is an Independent, International Research Institute

SEI - Africa Institute of Resource Assessment University of Dar es Salaam P. O. Box 35097, Dar es Salaam Tanzania Tel: +255-(0)766079061 SEI - Asia 15th Floor, Witthyakit Building 254 Chulalongkorn University Chulalongkorn Soi 64 Phyathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel+(66) 22514415 Stockholm Environment Institute, Working Paper 2014-03 SEI - Oxford Suite 193 266 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7DL UK Tel+44 1865 426316 SEI - Stockholm Kräftriket 2B SE -106 91 Stockholm Sweden Tel+46 8 674 7070 SEI - Tallinn Lai 34, Box 160 EE-10502, Tallinn Estonia Tel+372 6 276 100 SEI - U.S. 11 Curtis Avenue Somerville, MA 02144 USA Tel+1 617 627-3786 SEI - York University of York Heslington York YO10 5DD UK Tel+44 1904 43 2897 The Stockholm Environment Institute The emerging oil palm agro-industry in Palawan, the Philippines: SEI is an independent, international research institute. It has been Livelihoods, environment and corporate accountability engaged in environment and development issues at local, national, regional and global policy levels for more than a quarter of a century. SEI supports decision making for sustainable development by Rasmus Kløcker Larsen, Francisca Dimaano and Michael D. Pido bridging science and policy. sei-international.org STOCKHOLM ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE WORKING PAPER NO. 2014–3 THE EMERGING OIL PALM AGRO-INDUSTRY IN PALAWAN, THE PHILIPPINES: LIVELIHOODS, ENVIRONMENT AND CORPORATE ACCOUNTABILITY Rasmus Kløcker Larsen1, Francisca Dimaano2 and Michael D. Pido2 1. Stockholm Environment Institute 2. Palawan State University 1 THE OIL PALM AGRO-INDUSTRY IN PHILIPPINES: LIVELIHOODS AND CORPORATE ACCOUNTABILITY CONTENTS Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... 9 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 10 1. -

Review of Bigeye and Yellowfin Tuna Catches Landed in Palawan, Philippines

Review of bigeye and yellowfin tuna catches landed in Palawan, Philippines David G. Itano1 and Peter G. Williams2 On behalf of Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCFPC) November 2009 1 Pelagic Fisheries Research Program, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 2 Oceanic Fisheries Programme (OFP), Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), Noumea, New Caledonia Review of bigeye and yellowfin tuna catches landed in Palawan, Philippines P a g e | ii Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Background .......................................................................................................................... 2 3 Scope of the study ................................................................................................................ 2 4 Geography, Demographics and Climate of Palawan ............................................................... 3 5 Description of gears fishing for tuna in Palawan .................................................................... 4 5.1 General .................................................................................................................................................. 4 5.2 Fishing grounds and fish aggregation ................................................................................................... 5 5.3 Seasonality and environmental factors ................................................................................................ -

Region Name of Laboratory Iv-B Aborlan Medicare

REGION NAME OF LABORATORY IV-B ABORLAN MEDICARE HOSPITAL IV-B BARRETTO MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER IV-B BAYVIEW DOCTORS MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC & LABORATORY IV-B BERACHAH HOSPITAL IV-B BULALACAO COMMUNITY HOSPITAL IV-B CAMP GENERAL ARTEMIO RICARTE STATION HOSPITAL IV-B CITY HEALTH AND SANITATION DEPARTMENT LABORATORY IV-B CITY HEALTH LABORATORY AND SOCIAL HYGIENE CLINIC IV-B CLINICA PALAO IV-B CULION SANITARIUM & GENERAL HOSPITAL IV-B CUYO DISTRICT HOSPITAL IV-B DBS MULTISPECIALTY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER IV-B DELOS REYES MEDICAL CLINIC IV-B DIVINE GRACE CLINICAL LABORATORY IV-B DON MODESTO FORMILLEZA SR. MEMORIAL HOSPITAL IV-B DR. DAMIAN REYES PROVINCIAL HOSPITAL IV-B E. ASUNCION MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV-B ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION AND PUBLIC HEALTH LABORATORY IV-B GRACE MISSION HOSPITAL, INC. IV-B HOLY INFANT JESUS MEDICAL & DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC IV-B HOSPITAL OF THE HOLY CROSS IV-B ISIAH HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER IV-B ISIAH MULTISPECIALTY CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV-B JBMBS SPECIALTY CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER IV-B LAB CENTRAL MEDICAL LABORATORY IV-B LBR CLINICAL LABORATORY AND MEDICAL SERVICES IV-B LEONCIO GENERAL HOSPITAL IV-B LIFEQUEST MEDICAL CLINIC AND DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY IV-B LUBANG DISTRICT HOSPITAL IV-B LUNA GOCO MEDICAL CENTER IV-B MACATO-RUGA CLINICAL LABORATORY IV-B MARIA ESTRELLA GENERAL HOSPITAL, INC. IV-B MEDICAL CLINIC- TERESITA CARVAJAL MORALES M.D. MEDICAL MISSION GROUP HOSPITAL MULTIPURPOSE COOPERATIVE OF ORIENTAL IV-B MINDORO (MMGHMCOM) MEDICAL MISSION GROUP HOSPITALS AND HEALTH SERVICES COOPERATIVE OF THE IV-B PHILIPPINES - PUERTO PRINCESA CITY IV-B MEGA SPECIALIST LABORATORY REGION NAME OF LABORATORY IV-B MINDORO DOCTORS CLINICAL LABORATORY INC.