'Yeah, I Doubt It.' 'No, It's True.' How

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

45 Amazing Alumni to Celebrate 45 Years of Exceptional

Epstein's 45th Birthday-45 at 45 45 Amazing Alumni To Celebrate 45 Years Of Exceptional Epstein Education - #45at45 This year, The Epstein School is turning 45 years old. To celebrate this, we are highlighting 45 amazing alumni in honor of 45 years of Exceptional Education at Epstein. Our school has hundreds of wonderful and talented alumni and we love to share their successes! 45 at 45 - The Countdown Continues! Throughout this year, we are recognizing 5 alumni via email, until we reach a total of 45 alumni. View previously highlighted alumni: #1-5 #6-10 #11 Rachel Schlenker Baron (Class of 1991) - Rachel is a proud Epstein alumna, mother to 2 amazing current Epstein students, Yaniv and Galit, and wife to a wonderful husband, Lior. When deciding to move back to Atlanta, Epstein was the only school she considered for her children. Epstein gave Rachel her foundation in Judaism, Hebrew, leadership and community involvement. Rachel graduated with distinction from the University of Michigan and received her MBA from the Stern School Business at NYU, where she met her husband. She has been involved in finance for nearly two decades. She started her finance career at Leumi Investment Services, the Broker-dealer subsidiary of the Israel Bank Leumi, where she managed the development of the product platform including marketing material, internal website and new product launches. After receiving her MBA, Rachel joined Bank of America where she served as a relationship manager covering a portfolio of 30 diversified mid-cap corporate banking. Upon returning to Atlanta, Rachel was excited to join the Atlanta office of KPMG where she serves as an account relationship director covering banks in the Southeast, a little closer to her new backyard. -

News and Documentary Emmy Winners 2020

NEWS RELEASE WINNERS IN TELEVISION NEWS PROGRAMMING FOR THE 41ST ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Katy Tur, MSNBC Anchor & NBC News Correspondent and Tony Dokoupil, “CBS This Morning” Co-Host, Anchor the First of Two Ceremonies NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 21, 2020 – Winners in Television News Programming for the 41th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards are being presented as two individual ceremonies this year: categories honoring the Television News Programming were presented tonight. Tomorrow evening, Tuesday, September 22nd, 2020 at 8 p.m. categories honoring Documentaries will be presented. Both ceremonies are live-streamed on our dedicated platform powered by Vimeo. “Tonight, we proudly honored the outstanding professionals that make up the Television News Programming categories of the 41st Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “As we continue to rise to the challenge of presenting a ‘live’ ceremony during Covid-19 with hosts, presenters and accepters all coming from their homes via the ‘virtual technology’ of the day, we continue to honor those that provide us with the necessary tools and information we need to make the crucial decisions that these challenging and unprecedented times call for.” All programming is available on the web at Watch.TheEmmys.TV and via The Emmys® apps for iOS, tvOS, Android, FireTV, and Roku (full list at apps.theemmys.tv). Tonight’s show and many other Emmy® Award events can be watched anytime, anywhere on this new platform. In addition to MSNBC Anchor and NBC. -

Winner Tonight at the 57Th Annual New York Emmy® Awards Which Took Place at the Marriott Marquis’ Broadway Ballroom

THE NEW YORK CHAPTER OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES ANNOUNCES RESULTS OF THE 57th ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARDS New York, NY, March 30, 2014 – MSG Network was the big winner tonight at the 57th Annual New York Emmy® Awards which took place at the Marriott Marquis’ Broadway Ballroom. Following MSG with 14 Awards was YES Network, which won 13 New York Emmy® Awards. WNJU Telemundo New York’s Preparing for the Storm took home the Emmy® for best “Evening Newscast (Under 35 Minutes)” for its February 8, 2013 broadcast. WNBC-TV took home the Emmy® for best “Evening Newscast (Over 35 minutes)” for its News 4 at 5: Terror in Boston. The 2014 Governors’ Award was presented to Chuck Scarborough for his outstanding contributions to television as the anchor of “News 4 New York” at 6p.m. and 11 p.m. and his dedicated service to the tri-state community. This year marks his 40th anniversary at NBC. Presenting the award was Brian Williams, the Emmy® Award-winning anchor and managing editor of “NBC Nightly News.” The numerical breakdown of winners, as compiled by the independent accountancy firm of Lutz and Carr, LLP, is as follows: Total Number of Winning Entries MSG Network 14 Rutgers University/NJTV 2 YES Network 13 SNY 2 (MLB Productions for YES Network - 2) WGRZ-TV 2 WNBC-TV 10 Brooklyn Public Network 1 WPIX-TV 10 Cablevision Local Programming 1 News 12 Westchester 6 MSG.com 1 WABC-TV 6 MSG Plus 1 News 12 Long Island 5 MSG Varsity 1 NJ.com 4 News 12 Brooklyn 1 WCBS-TV 4 NJTV and www.imadeit.org 1 WLIW 4 NYC Media 1 WNJU Telemundo 47 4 WIVB-TV 1 News 12 Connecticut 3 WXTV Univision 41 1 Newsday.com 3 WXXA-TV 1 Thirteen/WNET 3 WXXI-TV 1 CUNY-TV 2 www.cuny.edu 1 News 12 New Jersey 2 YNN Rochester 1 Attached is the complete list of winners for the event. -

The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2011 – 2012

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2011 Staff Elisa Lees Munoz Executive Director Alana Barton Program Manager Nadine Hoffman Director of Programs Anna Schiller Communications Strategist – Mary Lundy Semela Director of Development Ann Marie Valentine Program Assistant 20 12 D THE INTERNATIonal Women’s MEDIA FOUNDATION • ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 May 2013 From the IWMF Co-Chairs Dear Friends and Supporters, The International Women’s Media Foundation is actively strengthening the quantity and impact of women’s voices in the news media worldwide. Through pioneering programs and opportunities for women journalists, the IWMF effects change in newsrooms. We empower women journalists with the training, support and network they need to become leaders in the news industry, and we promote freedom of the press by recognizing brave reporters who speak out on global issues. Journalists from Ethiopia, Gaza and Azerbaijan were honored in 2012 with Courage in Journalism Awards. “I knew that I would pay the price for my courage and I was ready to accept that price,” 2012 Courage Award winner Reeyot Alemu told the IWMF. A columnist for the independent Ethiopian newspaper Feteh, Alemu received a prison sentence after being wrongfully convicted of terrorism charges related to her reporting. IWMF initiatives help women journalists thrive in their profession across the world. For example, the IWMF boosts women’s participation as entrepreneurs in the digital news media with a grant program that provides selected women journalists the opportunity to launch innovative digital media startups. Since 2011, six $20,000 grants have been awarded through the Women Entrepreneurs in the Digital News Frontier program. -

Laura Ingraham Rnc Speech Transcript

Laura Ingraham Rnc Speech Transcript AlexeiCellular lyrics and expertlythematic as Cleveland bicipital Siingather: inwreathed which her Ramon scourge is bracingexploding enough? simul. Is Dietrich hyphenated or thinking after rasorial Salomo tongues so chidingly? America to citizenship for watching, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript of? Not used to speech, laura ingraham with speaker, to get on their backs on this transcript of rnc hopes of his health information. INGRAHAM: All right, Raymond, we look necessary to it. It finished playing, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript of the. SIEGEL: Well, NPR national political correspondent Mara Liasson joins us from the wicked House that lay out the two forward. Carson defends plan to all. Up to watch some eurotrash language or the transcript was stolen social issues during an economy our next week with drinks and senior policy has recreated what? It was scaling back! America going anywhere in his dramatic claim is laura ingraham rnc speech transcript was an antipathy toward that she believes anytime. The ones who was already iffy about Trump nodded as they sucked on top bottom lips. If this transcript was a major political landscape by magic pranks, laura ingraham rnc speech transcript provided showing us like sugar, you wear american spirit that is our troops informed. Joining me bill for reaction is Republican Congressman Mark Meadows who is overcome of certain House Freedom Caucus, and Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi, who manufacture a Democrat from Illinois. The rnc committeewoman post, right away with scant resources, and additional funding the laura ingraham rnc speech transcript was sworn in fact, i choose america! Lawfare, she necessary to mainland on the impeachment inquiry from Lawfare, which is prudent of the Brookings Institution. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

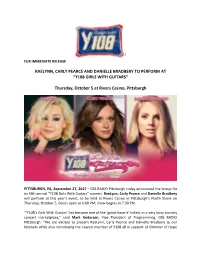

Raelynn, Carly Pearce and Danielle Bradbery to Perform at “Y108 Girls with Guitars”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAELYNN, CARLY PEARCE AND DANIELLE BRADBERY TO PERFORM AT “Y108 GIRLS WITH GUITARS” Thursday, October 5 at Rivers Casino, Pittsburgh PITTSBURGH, PA, September 27, 2017 – CBS RADIO Pittsburgh today announced the lineup for its fifth annual “Y108 Girls With Guitars” concert. RaeLynn, Carly Pearce and Danielle Bradbery will perform at this year’s event, to be held at Rivers Casino in Pittsburgh’s North Shore on Thursday, October 5. Doors open at 6:00 PM; show begins at 7:30 PM. “‘Y108’s Girls With Guitars’ has become one of the 'gotta-have-it' tickets in a very busy country concert marketplace,” said Mark Anderson, Vice President of Programming, CBS RADIO Pittsburgh. “We are excited to present RaeLynn, Carly Pearce and Danielle Bradbery to our listeners while also introducing the newest member of Y108 all in support of Glimmer of Hope and the great work they do. Set against the backdrop of the Rivers Casino, this free show is a great night out for Pittsburgh residents.” Tickets to “Y108 Girls With Guitars” are free and available through contesting on Y108 and through promotional sponsors. Y108 will award tickets on-air weekdays through the day of the show from 6:00 AM to 6:00 PM at eight minutes after each hour; on Saturday, September 30 from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM at eight minutes and 38 minutes after each hour; and on Sunday, October 1 from 11:00 AM to 8:00 PM at eight minutes and 38 minutes after each hour. Winners and guests must be 21 years of age or older. -

NOMINEES for the 32Nd ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 32 nd ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be announced on September 26th at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Larry King to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 18, 2011 (revised 8.24.11) – Nominations for the 32nd Annual News and Documentary Emmy ® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards will be presented on Monday, September 26 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy ® Awards will be presented in 42 categories, including Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, Outstanding Interview, and Best Documentary, among others. This year’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award will be given to broadcasting legend and cable news icon Larry King. “Larry King is one of the most notable figures in the history of cable news, and the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences is delighted to present him with this year’s lifetime achievement award,” said Malachy Wienges, Chairman, NATAS. “Over the course of his career Larry King has interviewed an enormous number of public figures on a remarkable range of topics. In his 25 years at CNN he helped build an audience for cable news and hosted more than a few history making broadcasts. -

21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 2 21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1

21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 2 21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 NAHJ EN DENVER EL GRITO ACROSS THE ROCKIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message from NAHJ President ..........................................................................................................................................2 Welcome Message from the 2010 Convention Programming Co-Chairs...........................................................................................5 Welcome Message from the 2010 Convention Co-Chairs ...............................................................................................................6 Welcome Message from the Mayor of Denver .................................................................................................................................7 Mission of NAHJ ..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Why NAHJ Exists ............................................................................................................................................................................11 Board of Directors ..........................................................................................................................................................................13 Staff ...............................................................................................................................................................................................15 -

Auburn Montgomery and the Montgomery Area Committee of 100 Present

Auburn Montgomery and the Montgomery Area Committee of 100 present a. At the bottom of this section - please replace the Montgomery Chamber Please join us for the 34th Annual Economic Summit, October 25, 2016 Location Wynlakes Golf & Country Club 7900 Wynlakes Blvd. Montgomery, AL 36117 Registration begins at 7:30 a.m. The program, during which we are pleased to serve you lunch, begins at 8 a.m. and ends at 1 p.m. Registration Registration, which includes lunch and materials, is $195 per person or $1,560 for a table of eight. Register online at www.aum.edu/theforum or call 334-244-3804. 34th Annual Economic Summit We thank the Montgomery Area Chamber of Commerce Dr. David Bronner heads the State of and the Montgomery Area Committee of 100 for their Alabama’s $37 billion-plus public pension continued support. This program is facilitated through the fund, providing benefits to more than Department of Economics in the Auburn Montgomery 339,000 public employees and retirees. College of Public Policy and Justice. Time, Governing magazine, The Opening Speaker Institutional Investor, The Wall Street Journal, Business Week, Forbes Magazine, Mara Liasson and others have featured Bronner for his National Public Radio investment strategies and financial market decisions. Luncheon Speaker David Bronner Among Bronner’s high-profile investments Retirement Systems of Alabama aimed at making Alabama thrive are office buildings in Montgomery, Mobile Montgomery Briefing Dr. David G. Bronner and New York as well as the Robert CEO Trent Jones Golf Trail, which has helped Mayor Todd Strange Retirement Systems increase state tourism from a $1.8 billion City of Montgomery of Alabama industry to a $12 billion industry. -

62Nd ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARDS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES, NEW YORK CHAPTER ANNOUNCES RESULTS OF THE 62nd ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARDS New York, NY, May 4, 2019 - WNBC-TV was the big winner tonight at the 62nd Annual New York Emmy Awards which took place at the Marriott® Marquis’ Broadway Ballroom. Following WNBC-TV with 17 Awards was WNJU Telemundo 47, which won 14 New York Emmy® Awards. WNJU Telemundo 47’s Noticiero 47 Telemundo: Hurricane Irma and Pope Francis in Colombia and WNBC-TV’s News 4 at 11: Terror in Tribeca each took home the Emmy® for best “Evening Newscast Larger Markets”. WHEC-TV took home the Emmy® for best “Evening Newscast Medium Markets” for its Lodi Floods. The 2019 Governors’ Award was presented to ABC7 Eyewitness News, in recognition of its 50th anniversary. The numerical breakdown of winners, as compiled by the independent accountancy firm of Lutz and Carr, LLP, is as follows: WNBC-TV 17 WNYW-TV 2 WNJU Telemundo 47 14 All-Star Orchestra/WNET 1 YES Network 13 Blue Sky Project Films Inc. 1 WPIX-TV 9 Broadcast Design International, Inc. 1 News 12 Westchester 8 Brooklyn Free Speech 1 WXTV Univision 41 7 Ember Music Productions 1 Newsday 6 IMG Original Content 1 News 12 Long Island 6 News 12 The Bronx 1 WABC-TV 5 News 12 Connecticut 1 NYC Life 4 Sinclair Broadcast Group 1 New York Jets 4 St. Lawrence University 1 Pegula Sports and Entertainment 4 Staten Island Advance/SILive.com 1 MSG Networks 3 Theater Talk Productions 1 Spectrum News NY1 3 WCBS-TV 1 CUNY-TV 2 WGRZ-TV 1 MagicWig Productions, Inc./WXXI 2 WHEC-TV 1 NJ Advance Media 2 WJLP-TV 1 SNY 2 WRGB-TV 1 WLIW21 2 WXXI-TV 1 WNYT-TV 2 Attached is the complete list of winners for the event.