Open-Ended Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Associate Artistic Director, Theatreworks, Singapore Associate Artist, the Substation, Singapore

Associate Artistic Director, Theatreworks, Singapore Associate Artist, The Substation, Singapore vertical submarine is an art collective from Singapore that consists of Joshua Yang, Justin Loke and Fiona Koh (in order of seniority). According to them, they write, draw and paint a bit but eat, drink and sleep a lot. Their works include installations, drawings and paintings which involve text, storytelling and an acquired sense of humour. In 2010, they laid siege to the Singapore Art Museum and displayed medieval instruments of torture including a fully functional guillotine. They have completed projects in Spain, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, The Philippines, Mexico City, Australia and Germany. Collectively they have won several awards including the Credit Suisse Artist Residency Award 2009, The President’s Young Talents Award 2009 and the Singapore Art Show Judges’ Choice 2005. They have recently completed a residency at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. MERITS 2009 President’s Young Talents 2009 Credit Suisse Art Residency Award 2005 Singapore Art Show 2005: New works, Judge’s Choice 2004 1st Prize - Windows @ Wisma competition, Wisma Atria creative windows display PROJECTS 2011 Incendiary Texts, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Dust: A Recollection, Theatreworks, Singapore Asia: Looking South, Arndt Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany Postcards from Earth, Objectifs – Center for Photography and Filmmaking, Singapore Open Studios, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, Australia Art Stage 2011, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore 2010 How -

Sherman ONG (B

Sherman ONG (b. 1971) Education 1995 National University of Singapore, LLB (Hons.), Singapore Selected Solo Exhibitions 2014 Spurious Stories from the Land and Water, Art Plural Gallery, Singapore 2010 ICON de Martell Photography Award, Institute of Contemporary Arts, Singapore Ticket Seller, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, USA 2009 Sherman Ong, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Australia 2008 Hanoi Monogatari (Hanoi Story), Zeit Foto Salon, Tokyo, Japan HanoiHaiku: Month of Photography Asia, 2902 Gallery, Singapore 2007 Missing You, Fukuoka Art Asian Museum, Fukuoka, Japan 2006 HanoiHaiku, Angkor Photography Festival, Siem Reap, Cambodia Selected Group Exhibitions 2014 Flux: Collective Exhibition, Art Plural Gallery, Singapore Lost in Landscape, MART – Museum of Contemporary Art of Ternto & Roverto, Italy The Disappearance, Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore 2013 Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (Cinema), Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia. Cinema Encounters: Sherman Ong, Casa Asia, Barcelona & Madrid, Spain Migrants (in)visibles, Espace Khiasma, Paris, France Motherland - Xiao Jing, Open House (Marina), Singapore 2012 Little Sun by Olafur Eliasson, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom Asia Serendipity, Teatro Fernando Gomez, Photo Espana Madrid, Spain Panorama, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore PIMP the TIMP Volume II, Galerie Lichtblick, 21st International Photoszene Cologne, Germany. Cross-Scape, GoEun Museum of Photography, Busan, Korea I want to remember, Rotterdam International Film Festival, Netherlands -

Only a Fragment

ONLY A FRAGMENT Eiffel Chong Minstrel Kuik May Sherman Ong 7 – 21 2015 Only a Fragment “A photograph Nowadays, we are constantly bombarded by the photo- and the strict visual structure, Eiffel is able to conjure a is only a graphed image, scattered everywhere in the urban breath of associations such as Color Field paintings to landscape, seducing us with their auratic quality, at the minimal abstraction. As in his other previous series, Eiffel fragment, same time attempting to sell something, while in cyber- considers the abstract concepts of life and death through an and with the space, the digital image mutate, grow, change via digital economical visual language, highlighting banal details such passage of time tools or disintegrate via sharing and usage. Furthermore, as soft clouds in the sky and the horizon line into delicate its moorings the act of taking a photograph has become an innate gesture textures. Furthermore their uniformed stillness links them to most people equipped with smartphones and mobile as one, and one is again reminded that all seas are actually come unstuck. digital devices. These photos captured anywhere using part of the same mass of water. Finally, there is a sense It drifts a mobile device could mean something for a moment of calmness fabricated by the images as one is given an away into a either as a way to document vital information or freeze opportunity to view nature before the intervention of man. soft abstract meaningful moments, but usually in time end up as hopeless digital relics forgotten in the phone's memory. -

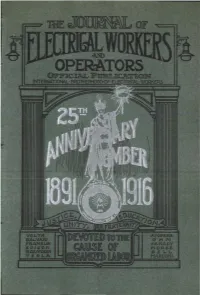

Electrical Workers and Operators

The Journal ot Electrical Workers and Operators OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and all Its Departments. OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ELECTRICAL WORKERS CHAS. P. FORD} International Secretary, GENERAL OFFICES: REISCR BUILDING SPRINGFIELD, ILL. Subscription, 26c per year, in advance. This Journal will not be held responsible for views exprelllled by corre8ponden•• The tenth of each month is the closiq date; an copy must be in our handa on or Won. Second Cia•• prhilejre applied for at the Post omc.. at Sprin",eld, IDlDOia. under Act of June I.th, 18e•• INDEX. A Quarter Century of Progress. .. 221-227 Around the Circuit. ................................... 271-272 Classified Directory .................................. 287-288 Correspondence ..................• . .. 245-271 Editorial ............................................. 237-241 Elementary Lessons ........................•......... 275-277 Executive Officers ................................... 235 In Memoriam ........................................ 228-234 Local Union Official Receipts .......................... 241-244 Local Union Directory .........._...................... 278-286 Notices ..................•••.....•................... 235-236 Things Electrical .................................... 272-275 THE JOURNAL OF ELECTRICAL WORKERS AND OPERATORS OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ELECTRICAL WORKERS Second CI ... privilege applied for at the Post Office at Springfield. Illinois. under Act of June 26th. 1906 Sinille Copies. 10 Cenb \70';.,. XVI, No.4 SPRINGFielD, ILL., NOVEMBER 1916. 25< per • Year in advance A Quarter Century of Progress ,p Twenty·five years ago this month, No c\About September 1st, 1890, a few men vember 21st, 1891, to be exact, the Broth· came together and against bitter and erhood was born. Attendants at the most senseless opposition formed what is birth pronounced it a bright hardy now Local No. -

Wong Lip Chin Galtd

WONG LIP CHIN GALTD Born in 1987, lives and works between Singapore & Shanghai. RELATED PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Adjunct lecturer at LASALLE College of the Arts. www.lasalle.edu.sg (2014 - 2018) EDUCATION 2009 Bachelor of Art (Fine Art -Printmaking) with Honours LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Sometimes I You Don‘t Dive Hard Enough. Yeo Workshop, Singapore 2015 Thousand Knives. Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore 2009 Now You See. Marina Mandarin Hotel, Singapore GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Strange Things, Singapore Arts Club, Singapore 2018 You don‘t need 100 editions, McNally School of Fine Arts, Singapore 2016 A Touch for the Now in Southeast Asia, Rarytas Art Foundation, Poznan, Poland Artling Pop Up, Artling, Singapore 2015 Plastic Myth. Asian Culture Centre Creation, Asian Culture Institute, GwangJu, Korea Asean 5. Wei-Ling Gallery at Victory Annexe, Penang, Malaysia Reflexion. Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore 2014 The Drawing Show. Yeo Workshop, Singapore Two Man Show. Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore 2013 Between Conversations. Yavuz Fine Art, Singapore Going Where. ShanghArt, Singapore 2009 RuckUs Rubix. Ng Eng Teng Gallery, NUS Museum, Singapore Art Fare. Housed in conjunction with Project Midas, Singapore 2007 27th Anniversary Exhibition of Printmaking Society. Singapore Tyler Print Institute, Singapore 2005 The HYPE Gallery. The Arts House, Singapore RELATED PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES (SELECTED) 2019 Twenty Twenty, Singapore Arts Club, Singapore 2016 ArtWeek at SAM. Exquisite Paradox. Front Lawn, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore Art Stage, Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore 2015 Formosa Art Show, Art at Project, Taipei, Taiwan Art Stage, Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore 2014 DRIVE, Gillman Barracks Public Art Project. “La Métamorphose Du Héros”, Galerie Michael Janssen, Singapore DRIVE, Gillman Barracks Public Art Project. -

Artist Biography

Artist Donna ONG ⺩美清 Born Singapore Works Singapore Artist Biography __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Education 2011 - 2012 MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore 2003 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK 1999 B.Sc. Architecture Bartlett Centre, University College London (UCL), UK __________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Year Selected Exhibitions 2017 Singapore: Inside Out Sydney, The Old Clare Hotel, Sydney, Australia After Utopia: Revisiting the Ideal in Asian Contemporary Art, Anne and Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, Adelaide, Australia The Tree as An Art Object, Wälderhaus Museum, Hamburg, Germany Art Stage Jakarta, FOST Gallery, Indonesia Art Stage Singapore, FOST Gallery, Singapore 2016 The Sharing Game: Exchange in Culture and Society, Kulturesymposium Weimar 2016, Galerie Eigenheim, Weimar, Germany For An Image, Faster Than Light, Yinchuan Biennale 2016, MoCA Yinchuan, China Five Trees Make A Forest, NUS Museum, Singapore* My Forest Has No Name, FOST Gallery, Singapore* 2015 After Utopia, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore The Mechanical Corps, Hartware MedienKunstVerein, Dortmund, Germany Prudential Eye Awards, ArtScience Museum, Singapore Prudential Singapore Eye, ArtScience Museum, Singapore 2014 Da Vinci: Shaping the Future, ArtScience Museum, Singapore Modern Love, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, Singapore Bright S’pore(s), Primo Marella Gallery, -

ANNEX a Complete List of Featured Artists and a I Light Marina Bay 2012 9 March – 1 April Marina Bay Featured Artists And

i Light Marina Bay 2012 9 March – 1 April Marina Bay ANNEX A Complete List of Featured Artists and Art Installations No Artist Gender Born Country of Birth Base 1 Aleksandra Stratimirovic * F 1968 Yugoslavia Sweden Andrew Daly F 1986 Australia Australia 2 Katherine Fife M 1990 Australia Australia 3 Angela Chong* F 1977 Singapore Singapore 4 Be Takerng Pattanopas* M 1965 Thailand Bangkok 5 BIBI M 1964 France France 6 Cornelia Erdmann* F 1976 Germany Hong Kong 7 Craig Walsh M 1966 Australia Australia 8 Dev Harlan M 1978 USA USA 9 Edwin Tan* M 1981 Singapore Singapore Groupe LAPS 10 Thomas Veyssiere (Director) M 1971 France France Hexogon Solution* 11 M 1976 Singapore Singapore Adrian Goh (Team Leader) 12 Li Hui M 1977 China China Light Collective* 13 Martin Lupton M 1969 UK UK Sharon Stammers F 1971 UK UK France, 14 Marine Ky* F 1966 Cambodia Cambodia, Australia Martin Bevz M 1986 Australia Australia 15 Kathryn Clifton F 1985 Australia Australia OCUBO* 16 Nuno Maya M 1978 Portugal Portugal Carolle Pumelle F 1964 Democratic Republic of Portugal Congo 17 Olivia d’Aboville* F 1986 Philippines Philippines 18 Olivia Lee* F 1985 Singapore Singapore 19 Ryf Zaini* M 1980 Singapore Singapore 20 Shinya Okuda M - Japan Singapore 21 StoryBox M 1975 New Zealand New Zealand Singapore Student 22 Showcase 1: - - - Singapore LASALLE College of the Arts 23 Singapore Student - - - Singapore Organised by Festival Direction by Held in i Light Marina Bay 2012 9 March – 1 April Marina Bay Showcase 2: School of the Arts Singapore 24 Takahiro Matsuo M 1979 Japan -

Ng Joon Kiat B

Ng Joon Kiat b. 1976, Singapore. Currently lives and works in Singapore Education 2002 Master of Arts (Fine Art) University of Kent at Canterbury (UK) 2001 Bachelor of Arts (Fine Art), with distinction Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University 1997 Associate Diploma in Visual Art (Painting) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Solo Exhibitions 2013 Works by Ng Joon Kiat Osage Atelier, Hong Kong 2012 Works by Ng Joon Kiat Osage Atelier, Hong Kong 2010 Green City II: A Collective Memory of Moving Images in Contemporary Painting Jendela (Visual Art Space), Esplanade, Singapore 2008 Garden City: A Study of Landscape Painting in Singapore TAKSU Singapore, Singapore 2007 Imagining a Geographical Presence: A Study of the Horizon in Contemporary Painting National Museum of Singapore, Singapore 2003 Imagining Science: An Interdisciplinary Painting Exhibition Artfolio, Raffles Hotel, Singapore Selected Group Exhibitions 2014 2014 Busan Biennale Special Project Co-curated by Joleen Loh. Kiswire Factory, Busan, South Korea Nature, in Process Space Cottonseed, Singapore Market Forces – Erasure: From Conceptualism to Abstraction Curated by Charles Merewether, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Art Basel Hong Kong 2014 Presented by Osage Gallery, Hong Kong Poetics of Materiality Curated by Charles Merewether, Osage Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2013 Singapore Biennale 2013 Singapore Art Museum, Singapore Local Futures Curated by Feng Boyi, He Xiangning Art Museum, Shenzhen, China Painting in Singapore Equator Art Projects, Gillman Barracks, Singapore -

CHNG SEOK TIN Born 1946, Singapore

CHNG SEOK TIN Born 1946, Singapore ARTIST STATEMENT A 1972 graduate in Western Painting from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Chng earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) at Hull, UK in 1979, Master of Arts in 1983 from New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, USA and Master of Fine Arts from the University of Iowa, USA in 1985. Chng is also the recipient of the Lee Foundation Study Awards from 1976-1979, the Cultural Foundation Award for postgraduate studies at Hornsey College of Arts from the Ministry of Culture in 1980 and recently, Woman of the Year Award in 2001. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 Gather & Disperse, Art-2 Gallery, Singapore Once Upon A Time, NUSS Guild House, Singapore 2011 Uncommon Wisdom, Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore 2008 Before & After… , Tainan County Cultural Center, Taiwan 2007 Wonders of Golden Needles, Jendela Gallery, Esplanade-Theatres by the Bay, Singapore Passion for Art – 35 Years of Works by Visual Artist Chng Seok Tin, Museum of Fine Arts (Cultural Affairs Bureau of Hsinchu County) and the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Kinmen County, Taiwan 2006 Evolution of Kim-chiam: From Dried Lily Bud to Rolling Red Dust, Telok Kurau Studios Gallery, Singapore 2005 Reflections of Paris, Orita.Sinclair.Int’l – Front Room Gallery, Singapore Passage to… , UN Secretariat South Lounge, New York, USA Blossoming of the Pomegranate, p-10, Singapore 2004 Sound of Vermont, Art-2 Gallery, Singapore 2003 Frames, within and without, Utterly Art Gallery, Singapore 2001 Attachments and Detachments: A Chinese Obsession, Gallery Evason Hotel, Singapore Life, Like Chess, Sculpture Square, Singapore 1996 Metamorphosis, Singapore Festival of Arts 1996, Fort Canning Arts Centre, Singapore 1994 Life, Cosmos Gallery, Hong Kong 1993 Games, National Museum Art Gallery, Singapore 1992 Games, d.p. -

The Mayor of Church Street

TENNESSEE TITANS ‘Cursed’ by mediocrity A franchise defined by its near-miss failures finds a new way to disappoint. SMALL BUSINESS P18 Driving like a Nashville millionaire Want a Ferrari or McLaren to impress your date? It can soon DaviLedgerDson • Williamson • sUmnER • ChEatham • Wilson RUthERFoRD • R be yours for a day – at a price. P16 The mayor of FIRST CHURCH NASHVILLE See Our Ad on page 32 Church Street oBERtson • maURY • DiCkson • montGomERY | November 15 – 21, 2013 www.nashvilleledger.com The power of information. Vol. 39 | Issue 46 F oR mer lY WESTVIEW sinCE 1978 Page 13 Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: David Taylor caters to Nashville’s GLBT Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, community with establishments patrons www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 Insurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, ‘wouldn’t mind bringing their mother to’ In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, -

Student Withdraws Complaint Fight Breaks out Between Theta CM, Job

FRIDAY Freshman Brian Lundy PARTAN DAILY becomes Spartan's leading receiver. Page 6 V 0L 99, No. 50 Published for San Jose State University since 1934 November 6, 1992 Student My achy-breaky back withdraws vi complaint Student cites lack of time BY KERRY PETERS Spartan Daily Stall Writer A complaint against the Campus Democrats alleging verbal and physical threats has been dropped. Marcia Holstrom, the student who filed the letter of complaint, decided to drop her charges. "It's just not worth it:' Holstrom said. "I don't have the time, and I don't have the energy to fight it:' The complaint, addressed to Dan Buerger, execu- tive assistant to Interim President J. Handel Evans, was filed last week after Holstrom interrupted a Campus Democrats press conference on Oct. 22 at Tower Quad. Holstrom said she interrupted the con- ference because she objected to the group's use of the university seal which she thought might lead people to believe SJSU was endorsing Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton for president. When Holstrom came forward at the event, sever- al members of the group hosting the event verbally attacked her, Holstrom said, and threatened to "take care of her later:' prompting her to file the complaint. However, members of the Campus Democrats and other people who participated in the event PATTI EAGAN SPARTAN DAILY denied Holstrom's charges. Carol Sullivan, In her step training class, pushes her students to the limit every Tuesday and Thursday at 1:30 p.m. in the Spartan Complex. Holstrom said that after talking to Phil Sanders, Step training is a type of aerobics that emphasizes a cardiovascular workout and muscle toning without the stress to the joints. -

Vertical Submarine Vertical Submarine Is an Art Collective From

Raffles Hotel Arcade • Unit #01-21 • 328 North Bridge Road • Singapore 188719 t: +65 6338 1962 • e: [email protected] www.chanhampegalleries.com Vertical Submarine Vertical Submarine is an art collective from Singapore comprising of three members–Joshua Yang, Justin Loke and Fiona Koh. Their works include installations, drawings and paintings, which involve text, storytelling and an acquired sense of humour. The collective has participated in projects in Spain, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, The Philippines, Mexico City, Australia and Germany. SELECT EXHIBITIONS 2015 Penetrations Chan Hampe Galleries, Singapore 2015 Residency and Research at Singapour en France – le festival Foundation La Roche Jacquelin, Anjou, France 2015 A View with a Room Musee d' art Contemporain (MAC) Lyon, Lyon, France 2015 Singapore Inside Out, Singapore Tourism Board (STB), SG50 Celebrations Beijing, London, New York, Singapore 2015 John Martin: The Butcher and The Surgeon Dialogic, Singapore 2015 Collective Form Objectifs – Center for Photography and Filmmaking, Singapore 2014 The Roving Eye: Contemporary Art from SE Asia ARTER (Vehbi Koc Foundation), Istanbul, Turkey 2014 Mirrors and Copulation Arter, Istanbul, Turkey 2014 Eville Singapore Night Festival 2014, artspace@222, Singapore 2014 Where have all the Tempinis gone? Coming Home, Passion Arts Month 2014, Singapore 2013 Sun Tzu’s Art of War Southeast Asia Pavilion, Beirut Art Fair, Beirut, Lebanon 2013 Hokkien Rhymes Esplanade, Singapore 2013 Wallflowers Gardens by the Bay Station, Thomson Line Art