Waking the Green Tiger: Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travels & Tourists in the Middle Kingdom: Two Insider Perspectives

The Newsletter | No.72 | Autumn 2015 12 | The Study Travels & tourists in the Middle Kingdom: two insider perspectives How then to keep a balance between the bursting Phenomena can be studied both as numeric data (trends) as well as tourism sector and the saturation of those places around the country that attract a multitude of visitors? What about that practices, that is, cultural tendencies. When it comes to tourism in never-ending debate between tourism and travel, between the massified and the ‘authentic’ experiences. “If you are relation to China the first approach manifests a clear symptom: China asking me about authenticity, I do not believe that visiting, let’s say, the Forbidden City is not an authentic experience: is more and more at the centre of the global tourism sector, either it is Beijing, it is China, you cannot avoid it. But Beijing is also Sanlitun and Chaoyang, two very wealthy and modern as a tourism destination, or as the source of an increasing number areas. Authenticity, then, can be found both in the different perspective from which you look at the Forbidden City, of outbound tourists. as well as in the overall travel experience that derives from all these apparent paradoxes. Many tourists, mainly foreigners, Stefano Calzati think of China in terms of its imperial past; my goal is to s how them that besides this legacy, China is something else nowadays.” ACCORDING TO THE MOST RECENT UN report,1 “tourist arrivals blue sky is boundless/You lit a cigarette at dusk/Looking at I was curious about differences, if any, between the reached 1,138 million in 2014, a 4.7% increase over the previous the yellow earth under your feet, the yellow walls/The yellow Western and the Chinese (self)perception of the Middle year. -

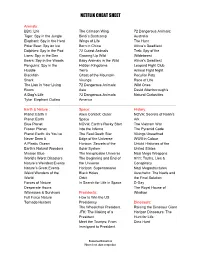

Netflix Cheat Sheet

NETFLIX CHEAT SHEET Animals: BBC: Life The Crimson Wing 72 Dangerous Animals: Tiger: Spy in the Jungle Bindi’s Bootcamp Australia Elephant: Spy in the Herd Wings of Life The Hunt Polar Bear: Spy on Ice Born in China Africa’s Deadliest Dolphins: Spy in the Pod 72 Cutest Animals Trek: Spy of the Lions: Spy in the Den Growing Up Wild Wildebeest Bears: Spy in the Woods Baby Animals in the Wild Africa’s Deadliest Penguins: Spy in the Hidden Kingdoms Leopard Fight Club Huddle Terra Animal Fight Night Blackfish Ghost of the Mountain Peculiar Pets Shark Virunga Race of LIfe The Lion in Your Living 72 Dangerous Animals: Wild Ones Room Asia David Attenborough’s A Dog’s Life 72 Dangerous Animals: Natural Curiosities Tyke: Elephant Outlaw America Earth & Nature : Space: History: Planet Earth II Alien Contact: Outer NOVA: Secrets of Noah’s Planet Earth Space Ark Blue Planet NOVA: Earth’s Rocky Start The Vietnam War Frozen Planet Into the Inferno The Pyramid Code Planet Earth: As You’ve The Real Death Star Vikings Unearthed Never Seen It Edge of the Universe WWII in Colour A Plastic Ocean Horizon: Secrets of the Untold Histories of the Earth’s Natural Wonders Solar System United States Mission Blue The Inexplicable Universe Nazi Mega Weapons World’s Worst Disasters The Beginning and End of 9/11: Truths, Lies & Nature’s Weirdest Events the Universe Conspiracy Nature’s Great Events Horizon: Supermassive Nazi Megastructures Weird Wonders of the Black Holes Auschwitz: The Nazis and World Orbit the Final Solution Forces of Nature In Search for Life in Space D-Day Desperate Hours: The Royal House of Witnesses & Survivors Presidents: Windsor Full Force Nature How to Win the US Tornado Hunters Presidency Dinosaurs: The Wheelchair President Raising the Dinosaur Giant JFK: The Making of a Horizon Dinosaurs: The President Hunt for Life Meet the Trumps: From Dino Hunt Immigrant to President HomeschoolHideout.com Please do not share or reproduce. -

Education Resource Service Catalogue 2012

Education Resource Service Catalogue 2012 1 ERS Catalogue 2012 This fully revised and updated catalogue is an edited list of our resources intended to provide customers with an overview of all the major collections held by the Education Resource Service (ERS). Due to the expansive nature of our collections it is not possible to provide a comprehensive holdings list of all ERS resources. Each collection highlights thematic areas or levels and lists the most popular titles. Our full catalogue may be searched at http://tinyurl.com/ERSCatalogue We hope that you find this catalogue helpful in forward planning. Should you have any queries or require further information please contact the ERS at the following address: Education Resource Service C/O Clyde Valley High School Castlehill Road Wishaw ML2 0LS TEL: 01698 403510 FAX: 01698 403028 Email: [email protected] Catalogue: http://tinyurl.com/ERSCatalogue Blog: http://ersnlc.wordpress.com/ 2 Your Children and Young People’s Librarian can….. The Education Resource Service is a central support service providing educational resources to all North Lanarkshire educational establishments. We also provide library based support and advice through our team of Children and Young People’s librarians in the following ways: Literacy • Information literacy activities • Effective use of libraries • Suggested reading lists • Author visits • Facilitate and lead storytelling sessions • Supporting literature circles • Transition projects Numeracy • Using the Dewey Decimal Classification System • Research skills • Transition projects Health and Wellbeing • Professional development resources • Reaction reading groups • Pupil librarians • Internet safety • Transition projects General • Pre-HMIe inspection support • Cross-curricular projects • Partnership working with public libraries, CL&D and other agencies 3 General Information Loan Period The normal loan period for all resources is 28 days. -

Fish & Seafood Product List

A FRESH CATCH SINCE 1987® FISH & SEAFOOD PRODUCT LIST t: 905.856.6222 | tf: 1.800.563.6222 | f: 905.856.9445 | e: [email protected] www.seacore.ca | 81 Aviva Park Drive, Vaughan, Ontario, Canada - L4L 9C1 Prices as of 8/31/2016 FISH & SEAFOOD PRODUCT LIST Tel. 905.856.6222 | 1.800.563.6222 | Fax. 905.856.9445 | [email protected] | seacore.ca Use CTRL+F to Search Product List ITEM NO. U/M A FRESH CATCH SINCE 1987® 100525 ALASKAN POLLOCK 5-7oz 8x2.5LB IVP Chem-Free OceanPrime China CS 120640 BASA FILLET FRESHNED BY/LB LB 101320 ALLIGATOR MEAT FILLET 12X1 LB VP * Chef Penny's CS 120579 BASA FILLET 7-9 454g 20/CASE SEA-RAY CS 101800 AMBERINES FRESH LB 120401 BASA H&G PREVIOUSLY FROZEN BY/LB FRESH PLU 7431 LB 105040 ANCHOVIE FILLETS 368G SAROLI 24/CS EA 684103 BASS SPOTTED TEXAS MIX BY/LB *VALUE ADDED* LB 104960 ANCHOVIES EA 763445 BASS STRIPED WILD FISHERMAN'S FRESH TW LB 105882 ANCHOVIES - ALICI FRESH ITALIAN BY/LB PLU-8014 LB 667018 BEEF JERKY ORIGINAL 90g 30/CS WCS JB90R CS 120135 ANCHOVIES - ALICI 6.61 LB FRESH ITALIAN CS 667020 BEEF JERKY PEPPERED HOT 90g 30/CS WCS CS 103120 ANCHOVIES FIL 560GR ALLESSIA 6/CS EA 128160 BELT FISH BRAZIL FRESH LB 103880 ANCHOVIES FIL MARINATED AGOSTINO RECCA 1KG 6/CS EA 128200 BELT FISH TRINIDAD FRESH LB 104880 ANCHOVIES FILLETS AGOSTINO RECCA 6/CS/230 EA 905205 BISQUE LOBSTER 5 L **PAIL** PL 1049600 ANCHOVIES FILLETS 150g 12/CASE ALLESSIA GLASS JAR CS 100320 BLACK BASS ALASKAN FIL SK-ON FRESH *** HOUSECUT CERTIFIED LB 120137 ANCHOVIES FILLETS 150GR ALLESSIA 12CS *WM* CS 145340 BLACK COD * STEAKS PF BY/LB HOUSECUT B.C. -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities

articles Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities Norman Myers*, Russell A. Mittermeier², Cristina G. Mittermeier², Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca³ & Jennifer Kent§ * Green College, Oxford University, Upper Meadow, Old Road, Headington, Oxford OX3 8SZ, UK ² Conservation International, 2501 M Street NW, Washington, DC 20037, USA ³ Centre for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, 2501 M Street NW, Washington, DC 20037, USA § 35 Dorchester Close, Headington, Oxford OX3 8SS, UK ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Conservationists are far from able to assist all species under threat, if only for lack of funding. This places a premium on priorities: how can we support the most species at the least cost? One way is to identify `biodiversity hotspots' where exceptional concentrations of endemic species are undergoing exceptional loss of habitat. As many as 44% of all species of vascular plants and 35% of all species in four vertebrate groups are con®ned to 25 hotspots comprising only 1.4% of the land surface of the Earth. This opens the way for a `silver bullet' strategy on the part of conservation planners, focusing on these hotspots in proportion to their share of the world's species at risk. The number of species threatened with extinction far outstrips populations and even ecological processes are not important mani- available conservation resources, and the situation looks set to festations of biodiversity, but they do not belong in this assessment. become rapidly worse1±4. This places a premium on identifying There are other types of hotspot10,11, featuring richness of, for priorities. How can we protect the most species per dollar invested? example, rare12,13 or taxonomically unusual species14,15. -

Video Titles.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA ADVANCED VISUALIZATION CENTER http://avc.web.usf.edu VIDEO TITLES LIST (July 2013) Funding for these resources was provided by the USF Student Technology Fee. Finding life beyond earth, 2011. (120 min.) Blu-ray Summary: Scientists are on the verge of answering one of the greatest questions in history: Are we alone? Finding Life Beyond Earth immerses audiences in the sights and sounds of alien worlds, while top astrobiologists explain how these places are changing how we think about the potential for life in our solar system. Frozen planet. The complete series, 2012. 3 videodiscs (300 min.) Blu-ray Summary: The Arctic and Antarctic remain the greatest wildernesses on Earth. The scale and beauty of the scenery and the sheer power of the elements, the weather, the rough ocean, and the ice is unmatched anywhere else on our planet. tells the compelling story of animals such as the wandering albatross, the adelie penguin, and the polar bear, and paints a portrait that will take your breath away, at a moment when, melting fast, the frozen regions of our planet may soon be changed forever. Severe clear, 2011. (93 min.) : Blu-ray Summary: The story of 1st Lt. Mike Scotti, who filmed with a mini-cam, sharing his thoughts through entries in a battlefield journal. Capturing the chaos and complexity of war, Severe Clear personifies the fear, turmoil, moral conundrum, heart-pounding reality, and sheer adrenaline rush of combat. An unrelenting account of frontline battle by U.S. Marines during Operation Iraqi Freedom, Severe Clear is a uniquely intimate, extreme, often horrific portrait of war. -

Exploring China Through Documentaries & Film

EEXXPPLLOORRIINNGG CCHHIINNAA TTHHRROOUUGGHH DDOOCCUUMMEENNTTAARRIIEESS && FFIILLMM National Consortium for Teaching about Asia East Asia Resource Center University of Washington Tese Wintz Neighbor Summer Institute 2014 EXPLORING CHINA THROUGH DOCUMENTARIES & FEATURE FILMS NOTE FROM TESE: If you do not have a decade or more to watch all of these movies(!) please check out this website from time to time for short documentaries from the Asia Society. Download free and use in your USING THIS RESOURCE GUIDE classroom. Note: The information regarding each film ASIA SOCIETY - CHINA GREEN has been excerpted directly from the http://sites.asiasociety.org/chinagreen/ website cited. Most of these sites include 1- China Green, a multimedia enterprise, documents 3 minute trailers. This is not a China’s environmental issues and strives to serve as a comprehensive list. Teacher guides are web forum where people “with an interest in China and available at a number of the documentary its environmental challenges can sites listed below and identified by the find interesting visual stories and Categories: share critical information about Air & Water resource icon. the most populous nation in the Energy & Climate Land & Urbanization world whose participation in the Life & Health There are different ways to access these solution to global environmental NGOs & Civil documentaries and films. Some can be Society problems, such as climate Tibetan Plateau downloaded directly from the web, some change, will be indispensable.” Wildlife can be found at local libraries, on Netflix, Pictures Talk Video Series or at the East Asia Resource Center. They http://sites.asiasociety.org/chinagreen/pictures-talk- can also be purchased directly from the video-series/ producer or from online stores. -

The Image of China in a BBC Documentary and Chinese Audiences’ Reception of It: the Case of the Chinese Are Coming

The Image of China in a BBC Documentary and Chinese Audiences’ Reception of it: The Case of The Chinese Are Coming by Wanwan Sun B.A., Communication University of China, Beijing, 2014 Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree Program in Global Communication) Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology Ó Wanwan Sun 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 Approval Name: Wanwan Sun Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title: The Image of China in a BBC Documentary and Chinese Audiences’ Reception of it: The Case of The Chinese Are Coming Supervisory Committee: Program Director: Dr. Alison Beale Yuezhi Zhao Senior Supervisor Professor Long Zhang Senior Supervisor Associate Professor School of Television Communication University of China Date Approved: August 19, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract China’s economic rise has led to competing images of the nation-state in the world’s media. Chinese audiences, for their part, are increasingly concerned with how the foreign media represent China. Against this background and taking into consideration the well-known reputation of BBC documentary film as one of the most authoritative Western media genres, this paper examines the 2011 BBC documentary film The Chinese Are Coming’s portrayal of China and its reception by selected graduate students at the Communication University of China and commentators at three online Chinese forums. The first part uses content analysis to break down the film into segments and examines its content in terms of seven subject areas and a series of key events, with a particular focus on the different tones of their treatment. -

China's Green Public Culture

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 5535–5557 1932–8036/20160005 China’s Green Public Culture: Network Pragmatics and the Environment JINGFANG LIU12 Fudan University, China G. THOMAS GOODNIGHT University of Southern California, USA The rates of environmental degradation and climate change accelerate and challenge taken-for-granted practices of living across the planet. China’s recent “smogpocalypse” illustrates how disruptive ecoevents necessitate complex, urgent alternatives and exchange. In this essay, we propose and analyze China’s Green Public Culture in terms of its players, networks, media, action, strategy, discourses, and cultural norm. The divergent communication activities of 21st-century green public culture in China are assembled as network pragmatics that cultivate experience, connect practices, tie alliances, express differences, and circulate controversy. Thus, we identify distinctive, emerging networks of cooperation and contestation, the vectors of dissensus that bid to generate and shape resources requisite for living in the Anthropocene. Keywords: public culture, environmentalism, China, network pragmatics, dissensus, Anthropocene The Environment and the Anthropocene In 2000, Nobel Prize–winning scientist Paul Crutzen named the current era as the Anthropocene, a time when “humans are becoming the dominant force for change on earth” (Crutzen & Schwägerl, 2011, para. 2). The Earth System Governance Project (Biermann et al., 2012) concludes that changing course and steering away from tipping points that “might lead to rapid and irreversible change . [and] fundamental reorientation and restructuring of national and international institutions toward more effective Earth system governance and planetary stewardship are necessary” (p. 1306). Such a turn hinges on a breakthrough of similar scope and magnitude in the study of communication: the marshaling of networked cultural resources engaged to address and contest environmental change. -

Otter Films Ltd Otter Films Films And/Or Produces Documentaries for Television And

Otter Films Ltd Otter Films films and/or produces documentaries for television and non- broadcast commissioners. The company is based in the west of Scotland. Photography credits include: Planet Earth II. BBC1 The Hunt BBC1. BAFTA and Wildscreen awards for best cinematography Hebrides - Islands on the Edge (4x60' in association with Maramedia for BBC Scotland, narrated by Ewan McGregor). Wildscreen award for best series Natural World - The Amber Time Machine (50’ Otter Films production for BBC2, presented by David Attenborough). Wildscreen Festival Finalist Natural World - Otters in the Stream of Life. (50’ Otter Films production for BBC2 and Discovery Channel) . On effect of the Gulf Stream on the wildlife of the west coast of Scotland Frozen Planet (7x60’ BBC1) BAFTA, Emmy, Wildscreen and Jackson Hole Festival awards for Cinematography team Wild Arabia (3x60' BBC). Emmy nomination for Cinematography team Yellowstone (3x60’ BBC2). BAFTA for Cinematography team. Emmy nomination for Cinematography Life (8x60’ BBC2) . Emmy for Cinematography Life Stories. BBC1 Wild China (6x50’ BBC2). Emmy for Cinematography Scottish Beaver Trial (for Scottish Wildlife Trust) Wild North America (Wild Horizons Ltd for Discovery Channel) Wild Americas (4x60’ National Geographic Television) Wild Britannia (3x60’ BBC) South Pacific (5x50’ BBC2) Taynish - A Rare and Special Place (for Scottish Natural Heritage) Big Cat Live (8 programmes for BBC1 October 2008) Glenmore 24 and Glenmore: Forest, Lochs…and More (for Forestry Commission Scotland in association with -

Barnaby Taylor

Barnaby Taylor Composer Barnaby is an Emmy-award winning composer, best known for his scores for landmark BBC series such as Wild Arabia (2013), the critically acclaimed Nature’s Great Events (2009) and Frozen Planet: On Thin Ice (2011), winner of the inaugural Music and Sound Award for Best Original Composition for TV. Drama credits include three seasons of the RTS Award-winning The Indian Doctor. Barnaby's first feature film, Camera Trap, directed by Alex Verner, will be released in by Pinewood/Cinema NX later this year, 2014. Music has always been a part of Barnaby’s life. He grew up around the folk music scene of which his singer-songwriter father, Allan Taylor, was a major part. Other interests led him to do a zoology degree that got him his first production jobs, as a film researcher at the BBC Natural History Unit and later at Icon Films, Bristol. However, this production work sparked his ambition to write music for picture and he was soon drawn back to his musical roots. Barnaby is sought after for his versatile, intuitive approach, and talent for working across musical genres. His scores range from the gritty and hard-hitting Calling the Shots (2005), a feature-length documentary for National Geographic on the Israeli Reuters News Agency, to lyrical acoustic scores, as heard in the BBC’s Bear Family and Me (2011). Barnaby works regularly with top-flight orchestras such as the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the BBC Concert Orchestra, to produce rich and dramatic scores, as heard in the three-part BBC series Ganges (2007) and, most recently, in the BBC’s Wild Arabia where the orchestral score was augmented with percussion and ethnic instruments recorded at Abbey Road studios.