IPGS-2009-Summary-Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (C

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (c. 51)i, ii An Act to make new provision with respect to public records and the Public Record Office, and for connected purposes. [23rd July 1958] General responsibility of the Lord Chancellor for public records. 1. - (1) The direction of the Public Record Office shall be transferred from the Master of the Rolls to the Lord Chancellor, and the Lord Chancellor shall be generally responsible for the execution of this Act and shall supervise the care and preservation of public records. (2) There shall be an Advisory Council on Public Records to advise the Lord Chancellor on matters concerning public records in general and, in particular, on those aspects of the work of the Public Record Office which affect members of the public who make use of the facilities provided by the Public Record Office. The Master of the Rolls shall be chairman of the said Council and the remaining members of the Council shall be appointed by the Lord Chancellor on such terms as he may specify. [(2A) The matters on which the Advisory Council on Public Records may advise the Lord Chancellor include matters relating to the application of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 to information contained in public records which are historical records within the meaning of Part VI of that Act.iii] (3) The Lord Chancellor shall in every year lay before both Houses of Parliament a report on the work of the Public Record Office, which shall include any report made to him by the Advisory Council on Public Records. -

Choose Europe! Join for the Opening of the New European Parliament!

CHOOSE EUROPE! JOIN FOR THE OPENING OF THE NEW EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT! 1st of July 2019 | Strasbourg, France Citizens’ Agora European Youth Centre Strasbourg 30, rue Pierre de Coubertin, 67000 A new Parliament for a new Europe European Parliamentary Association 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 2nd of July 2019 | Strasbourg, France Rally In front of the European Parliament 1 Avenue du Président Robert Schuman INTRODUCTION We have a newly elected Europe Parliament. It should become the front-runner in promoting a new Europe. Join us in Strasbourg for the opening session on 1-2 July to voice our demands for a more democratic, more social, more federal - a sovereign Europe! We are organising a 2 days bus trip from Brussels. The European Union has been “at a critical junction” for far too long. Radical reforms of the Euro, unity on security and defence, European democracy are urgently needed. Meanwhile Brexit looms, nationalism is on the rise, and citizens are puzzled on what Europe brings and where it is heading to. The next term of the European Parliament will be crucial to put Europe on a new course. The history of the European Union is one of citizens gathering and calling on elected leaders for more decisive steps towards political unity for the European people. Join us in Strasbourg to show that citizens support a federal Europe and engage with federalist members of the European Parliament on how to promote federalist goals in the newly elected Parliament. EU national leaders have failed us. European integration by intergovernmental cooperation has the EU stuck in a status quo that could well be its downfall. -

European Parliament Elections 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 Updated 12 March 2014 Overview of Candidates in the United Kingdom Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: VOTING METHOD IN THE UK ................................................................ 3 4.0 PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW OF CANDIDATES BY UK CONSTITUENCY ............................................ 3 5.0 ANNEX: LIST OF SITTING UK MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ................................ 16 6.0 ABOUT US ............................................................................................................................. 17 All images used in this briefing are © Barryob / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL © DeHavilland EU Ltd 2014. All rights reserved. 1 | 18 European Parliament Elections 2014 1.0 Introduction This briefing is part of DeHavilland EU’s Foresight Report series on the 2014 European elections and provides a preliminary overview of the candidates standing in the UK for election to the European Parliament in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the election for the country’s 73 Members of the European Parliament will be held on Thursday 22 May 2014. The elections come at a crucial junction for UK-EU relations, and are likely to have far-reaching consequences for the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe: a surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) could lead to a Britain that is increasingly dis-engaged from the EU policy-making process. In parallel, the current UK Government is also conducting a review of the EU’s powers and Prime Minister David Cameron has repeatedly pushed for a ‘repatriation’ of powers from the European to the national level. These long-term political developments aside, the elections will also have more direct and tangible consequences. -

WEEK in BRUSSELS Week Ending Friday 23 January

WEEK IN BRUSSELS Week ending Friday 23 January SMMT strengthens UK auto EU to support studies on dialogue with EU electric vehicle traffic SMMT held its reception in Brussels ‘The UK development automotive industry in Europe’ this week. The reception brought together senior automotive industry The EU’s TEN-T Programme will back a market study executives, UK and EU government officials, MEPs and a pilot on the deployment of electric vehicles and and representatives of the European Commission. A their charging infrastructure along the main highways keynote speech was delivered by Lord Hill, in southern Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany. Commissioner for Financial Stability, Financial The €1 million project aims to contribute to removing Services and Capital Markets Union, in which he barriers for long distance ‘green’ travel across announced the re-launch of the European borders. One of the main barriers to the widespread Commission’s CARS 2020 initiative. Also speaking at use of electric vehicles on European roads is lack of the event were Glenis Willmott MEP, Syed Kamall convenient service stations and their incompatibility MEP and Mike Hawes, SMMT Chief Executive. The with other kinds of vehicles. This project will carry out event presented a key opportunity to demonstrate the feasibility studies on consumer preferences and user strength and importance of the UK automotive acceptance of electric vehicles and the related industry to European colleagues, and to emphasise charging infrastructure, as well as the supporting how having a strong voice in Europe is critical to the consumer services. It will also make a pilot continuing success of the UK automotive sector. -

A Guide to the EU Referendum Debate

‘What country, friends, is this?’ A guide to the EU referendum debate ‘What country, friends, is this?’ A guide to the EU referendum debate Foreword 4 Professor Nick Pearce, Director of the Institute for Policy Research Public attitudes and political 6 discourses on the EU in the Brexit referendum 7 ‘To be or not to be?’ ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ and other clichés: the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership Dr Nicholas Startin, Deputy Head of the Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 16 The same, but different: Wales and the debate over EU membership Dr David Moon, Lecturer, Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 21 The EU debate in Northern Ireland Dr Sophie Whiting, Lecturer, Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 24 Will women decide the outcome of the EU referendum? Dr Susan Milner, Reader, Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 28 Policy debates 29 Brexit and the City of London: a clear and present danger Professor Chris Martin, Professor of Economics, Department of Economics 33 The economics of the UK outside the Eurozone: what does it mean for the UK if/when Eurozone integration deepens? Implications of Eurozone failures for the UK Dr Bruce Morley, Lecturer in Economics, Department of Economics 38 Security in, secure out: Brexit’s impact on security and defence policy Professor David Galbreath, Professor of International Security, Associate Dean (Research) 42 Migration and EU membership Dr Emma Carmel, Senior Lecturer, Department of Social & Policy Sciences 2 ‘What country, friends, is this?’ A guide to the EU referendum debate 45 Country perspectives 46 Debating the future of Europe is essential, but when will we start? The perspective from France Dr Aurelien Mondon, Senior Lecturer, Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 52 Germany versus Brexit – the reluctant hegemon is not amused Dr Alim Baluch, Teaching Fellow, Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies 57 The Brexit referendum is not only a British affair. -

Appendix to Memorandum of Law on Behalf of United

APPENDIX TO MEMORANDUM OF LAW ON BEHALF OF UNITED KINGDOM AND EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARIANS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER’S MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION LIST OF AMICI HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT House of Lords The Lord Ahmed The Lord Alderdice The Lord Alton of Liverpool, CB The Rt Hon the Lord Archer of Sandwell, QC PC The Lord Avebury The Lord Berkeley, OBE The Lord Bhatia, OBE The Viscount Bledisloe, QC The Baroness Bonham-Carter of Yarnbury The Rt Hon the Baroness Boothroyd, OM PC The Lord Borrie, QC The Rt Hon the Baroness Bottomley of Nettlestone, DL PC The Lord Bowness, CBE DL The Lord Brennan, QC The Lord Bridges, GCMG The Rt Hon the Lord Brittan of Spennithorne, QC DL PC The Rt Hon the Lord Brooke of Sutton Mandeville, CH PC The Viscount Brookeborough, DL The Rt Hon the Lord Browne-Wilkinson, PC The Lord Campbell of Alloway, ERD QC The Lord Cameron of Dillington The Rt Hon the Lord Cameron of Lochbroom, QC The Rt Rev and Rt Hon the Lord Carey of Clifton, PC The Lord Carlile of Berriew, QC The Baroness Chapman The Lord Chidgey The Lord Clarke of Hampstead, CBE The Lord Clement-Jones, CBE The Rt Hon the Lord Clinton-Davis, PC The Lord Cobbold, DL The Lord Corbett of Castle Vale The Rt Hon the Baroness Corston, PC The Lord Dahrendorf, KBE The Lord Dholakia, OBE DL The Lord Donoughue The Baroness D’Souza, CMG The Lord Dykes The Viscount Falkland The Baroness Falkner of Margravine The Lord Faulkner of Worcester The Rt Hon the -

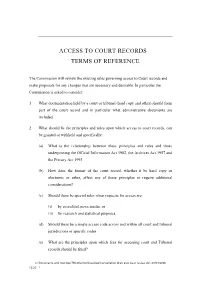

Access to Court Records – Terms of Reference

ACCESS TO COURT RECORDS – TERMS OF REFERENCE The Commission will review the existing rules governing access to Court records and make proposals for any changes that are necessary and desirable. In particular the Commission is asked to consider: 1 What documentation held by a court or tribunal (hard copy and other) should form part of the court record and in particular what administrative documents are included. 2 What should be the principles and rules upon which access to court records, can be granted or withheld and specifically: (a) What is the relationship between these principles and rules and those underpinning the Official Information Act 1982, the Archives Act 1957 and the Privacy Act 1993 (b) How does the format of the court record, whether it be hard copy or electronic or other, affect any of these principles or require additional considerations? (c) Should there be special rules when requests for access are: (i) by accredited news media; or (ii) for research and statistical purposes (d) Should there be a single access code across and within all court and tribunal jurisdictions or specific codes (e) What are the principles upon which fees for accessing court and Tribunal records should be fixed? C:\Documents and Settings\TMcGlennon\Desktop\Consultation draft post peer review.doc 29/03/2006 12:22 1 3 What should be the principles and rules governing disclosure of documentation held by a Court or Tribunal which is not part of a court record? 4 What should be the principles and rules under which court staff operates when handling access requests. -

On Faithfulness and Factuality in Abstractive Summarization

On Faithfulness and Factuality in Abstractive Summarization Joshua Maynez∗ Shashi Narayan∗ Bernd Bohnet Ryan McDonald Google Research fjoshuahm,shashinarayan,bohnetbd,[email protected] Abstract understanding how maximum likelihood training and approximate beam-search decoding in these It is well known that the standard likelihood models lead to less human-like text in open-ended training and approximate decoding objectives text generation such as language modeling and in neural text generation models lead to less human-like responses for open-ended tasks story generation (Holtzman et al., 2020; Welleck such as language modeling and story gener- et al., 2020; See et al., 2019). In this paper we ation. In this paper we have analyzed limi- investigate how these models are prone to gener- tations of these models for abstractive docu- ate hallucinated text in conditional text generation, ment summarization and found that these mod- specifically, extreme abstractive document summa- els are highly prone to hallucinate content that rization (Narayan et al., 2018a). is unfaithful to the input document. We con- Document summarization — the task of produc- ducted a large scale human evaluation of sev- eral neural abstractive summarization systems ing a shorter version of a document while preserv- to better understand the types of hallucinations ing its information content (Mani, 2001; Nenkova they produce. Our human annotators found and McKeown, 2011) — requires models to gener- substantial amounts of hallucinated content in ate text that is not only human-like but also faith- all model generated summaries. However, our ful and/or factual given the document. The exam- analysis does show that pretrained models are ple in Figure1 illustrates that the faithfulness and better summarizers not only in terms of raw factuality are yet to be conquered by conditional metrics, i.e., ROUGE, but also in generating text generators. -

Economy & Autonomy Blairfare: , Third-Way Disability and Dependency in Britain Introduction in This Paper We Intend to Explo

Economy & Autonomy Blairfare: , Third-Way Disability and Dependency in Britain Jennifer Harris University of Central Lancashire, UK BobSapey Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK John Stewart Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Introduction In this paper we intend to explore the social policy changes in relation to disabled people which are taking place in the United Kingdom, particularly since the election of the Labour government on May 1, 1997. We intend to first examine the key differences between this govern- ment and previous administrations and then to describe the policy changes which have occurred. We shall describe certain historical aspects of British social policy which are relevant to our analysis, a description that itself will involve an evaluation of the power structures that are emerging. The term which has been commonly used to describe this government's approach to economic and social policy is the "third way" and, while we acknowledge the value of this term in that it implies an alternative to either a collectivist or anti-collectivist approach to welfare (George and Wilding 1976), we have chosen to describe the policies we are examining as "Blairfare." This term, a combination of Prime Minister Tony Blair's last name and welfare, is intended to signify the rather personal character of "the third way" in Britain. Globalisation and the Nation-State For the past couple of years, the United Kingdom has had a Labour government but, unlike the experience of previous Labour and Conservative administrations, under the leadership of Prime Minister Blair we have been witnessing one of the greatest constitutional shake-ups this century. -

The European Conservatives and Reformists in the European Parliament

The European Conservatives and Reformists in the European Parliament Standard Note: SN/IA/6918 Last updated: 16 June 2014 Author: Vaughne Miller Section International Affairs and Defence Section Parties are continuing negotiations to form political groups in the European Parliament (EP) following European elections on 22-25 May 2014. This note looks at the future composition of the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), which was established by UK Conservatives when David Cameron took them out of the centre-right EPP-ED group in 2009. It also considers what the entry of the German right-wing Alternative für Deutschland group into the ECR group might mean for Anglo-German relations. The ECR might become the third largest political group in the EP, although this depends on support for the Liberals and Democrats group. The final number and composition of EP political groups will not be known until after 24 June 2014, which is the deadline for registering groups. For detailed information on the EP election results, see Research paper 14/32, European Parliament Elections 2014, 11 June 2014. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. -

Exclusive Interview with Dr

State: A Last Resort for People Exclusive interview with Dr. Syed Kamall Conducted by Bardia Garshasbi in London– July 2014 Syed Kamall is a phenomenon in his own right. He comes from an ordinary Guyanese family who migrated to London in mid-1950s. His father was a bus driver, and now at the age of 47, he is the leader of the Britain’s Conservative Party in the European Parliament, representing the people of London in that parliament since 2005, when he was only 38! Having degrees from some of the world’s most prestigious universities (London School of Economics and City University London) Dr. Kamall also chairs the European Conservatives and Reformist Group, the EU Parliament’s third largest group with 70 MEPs who are campaigning for urgent reform of the EU and of whom Syed is, as he proudly puts it, “the first group leader from an ethnic minority and the first Muslim ever”. Dr. Kamall is one of the few successful and highly educated politicians in Europe who does not come from an elite background or rich family. His path to success has been uphill and demanding. He has firsthand knowledge of the challenges low-income families are facing in their daily lives. That is why the relief of poverty has always been a top priority for him. He works tirelessly to find ways to tackle poverty by educating the young and by creating incentives and equal opportunities for hard- working people. His constituents in London and his peers in both Britain and Europe know him for his intelligence, decency, and eloquence. -

Mercyhurst Magazine

tsA VOL. 21, ISSUE 1 NOVEMBER 2004 -from fKe. Editor It happens every year. That moment of clarity when I realize how much work behind the scenes has been necessary to fuel Mercyhurst on a day-to-day basis, laying the foundation for this institution to evolve into exactly what it has become. Sometimes it strikes me when the finishing touches are being discussed at a planning meeting for com mencement, usually only days before the celebration begins and hundreds of family members flood through the Gates. Sometimes it happens as I look out over the crowds gathered for the annual Fourth of July event hosted by Mercyhurst College, knowing that our maintenance and security staffs have been on the clock for hours, and have little to no hope of going home any time soon. Sometimes I am simply walking across our beautiful campus when I start thinking about the people who keep the windows clean, the weeds pulled, our students in the right class with the right professor, and the freshmen snuggled safely in their residence halls (and the RIGHT residence hall to boot). I consider the students who dedicate hours organizing and supporting events such as Christmas on Campus, the college's March of Dimes WalkAmerica team and fund-raisers like Rotoracfs 5K run. The thought always brings a smile to my face, a mix of pride and awe at what we achieve every single day. To be honest, this year it took on new significance when, as a novice homeowner, I realized anew how much effort is invested in keeping our campus functioning.