Stellar and Galactic Astronomy Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confinement and Exotic Meson Spectroscopy at 12Gev JLAB

174 Brazilian Journal of Physics, vol. 33, no. 2, June, 2003 Confinement and Exotic Meson Spectroscopy at 12GeV JLAB Adam Szczepaniak Physics Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Received on 30 October, 2002 Phenomenology of gluonic excitations and possibilities for searches of exotic mesons at JLab are discussed. I Introduction O(104) number. For technical reasons dynamical evolu- tion is studied by replacing the Minkowski by the Euclidean Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) represents part of the metric thereby converting to a statistical systems and using Standard Model which describes the strong interactions. Monte Carlo methods to evaluate the partition function. The fundamental degrees of freedom are quarks – the mat- In parallel many analytical many-body techniques have ter fields, and gluons – the mediators of the strong force. been employed to identify effective degrees of freedom and Quarks and gluons are permanently confined into hadrons, numerous approximation schemes have been advanced to e.g. protons, neutrons and pions, to within distance scales describe the soft structure and interactions of hadrons, e.g. of the order of 1fm = 10¡15m. Hadrons are bound by the constituent quark model, bag and topological soliton residual strong forces to form atomic nuclei. Thus QCD models, QCD sum rules, chiral lagrangians, etc. determines not only the quark-gluon dynamics at the sub- In this talk I will focus on the physics of soft gluonic ex- subatomic scale but also the interactions between nuclei at citations and their role in quark confinement. Gluons carry the subatomic scale and even the nuclear dynamics at a the strong force, and since on a hadronic scale the light u and macroscopic level, e.g. -

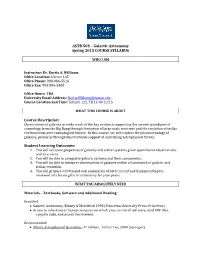

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS WHO I AM Instructor: Dr. Kurtis A. Williams Office Location: Science 145 Office Phone: 903-886-5516 Office Fax: 903-886-5480 Office Hours: TBA University Email Address: [email protected] Course Location and Time: Science 122, TR 11:00-12:15 WHAT THIS COURSE IS ABOUT Course Description: Observations of galaxies provide much of the key evidence supporting the current paradigms of cosmology, from the Big Bang through formation of large-scale structure and the evolution of stellar environments over cosmological history. In this course, we will explore the phenomenology of galaxies, primarily through observational support of underlying astrophysical theory. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. You will calculate properties of galaxies and stellar systems given quantitative observations, and vice-versa. 2. You will be able to categorize galactic systems and their components. 3. You will be able to interpret observations of galaxies within a framework of galactic and stellar evolution. 4. You will prepare written and oral summaries of both current and fundamental peer- reviewed articles on galactic astronomy for your peers. WHAT YOU ABSOLUTELY NEED Materials – Textbooks, Software and Additional Reading: Required: • Galactic Astronomy, Binney & Merrifield 1998 (Princeton University Press: Princeton) • Access to a desktop or laptop computer on which you can install software, read PDF files, compile code, and access the internet. Recommended: • Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities, 4th Edition, Arthur Cox, 2000 (Springer) Course Prerequisites: Advanced undergraduate classical dynamics (equivalent of Phys 411) or Phys 511. HOW THE COURSE WILL WORK Instructional Methods / Activities / Assessments Assigned Readings There is far too much material in the text for us to cover every single topic in class. -

PHYS 1302 Intro to Stellar & Galactic Astronomy

PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy University of Houston-Downtown Course Prefix, Number, and Title: PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy Credits/Lecture/Lab Hours: 3/2/2 Foundational Component Area: Life and Physical Sciences Prerequisites: Credit or enrollment in MATH 1301 or MATH 1310 Co-requisites: None Course Description: An integrated lecture/laboratory course for non-science majors. This course surveys stellar and galactic systems, the evolution and properties of stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies, the properties of interstellar matter, cosmology and the effort to find extraterrestrial life. Competing theories that address recent discoveries are discussed. The role of technology in space sciences, the spin-offs and implications of such are presented. Visual observations and laboratory exercises illustrating various techniques in astronomy are integrated into the course. Recent results obtained by NASA and other agencies are introduced. Up to three evening observing sessions are required for this course, one of which will take place off-campus at George Observatory at Brazos Bend State Park. TCCNS Number: N/A Demonstration of Core Objectives within the Course: Assigned Core Learning Outcome Instructional strategy or content Method by which students’ Objective Students will be able to: used to achieve the outcome mastery of this outcome will be evaluated Critical Thinking Utilize scientific Star Property Correlations – They will be instructed to processes to identify students will form and test prioritize these properties in Empirical & questions pertaining to hypotheses to explain the terms of their relevance in Quantitative natural phenomena. correlation between a number of deciding between competing Reasoning properties seen in stars. -

The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459

Whitworth et al.: The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459 The Formation of Brown Dwarfs: Theory Anthony Whitworth Cardiff University Matthew R. Bate University of Exeter Åke Nordlund University of Copenhagen Bo Reipurth University of Hawaii Hans Zinnecker Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam We review five mechanisms for forming brown dwarfs: (1) turbulent fragmentation of molec- ular clouds, producing very-low-mass prestellar cores by shock compression; (2) collapse and fragmentation of more massive prestellar cores; (3) disk fragmentation; (4) premature ejection of protostellar embryos from their natal cores; and (5) photoerosion of pre-existing cores over- run by HII regions. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Their relative importance probably depends on environment, and should be judged by their ability to reproduce the brown dwarf IMF, the distribution and kinematics of newly formed brown dwarfs, the binary statis- tics of brown dwarfs, the ability of brown dwarfs to retain disks, and hence their ability to sustain accretion and outflows. This will require more sophisticated numerical modeling than is presently possible, in particular more realistic initial conditions and more realistic treatments of radiation transport, angular momentum transport, and magnetic fields. We discuss the mini- mum mass for brown dwarfs, and how brown dwarfs should be distinguished from planets. 1. INTRODUCTION form a smooth continuum with those of low-mass H-burn- ing stars. Understanding how brown dwarfs form is there- The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed on the- fore the key to understanding what determines the minimum oretical grounds by Kumar (1963) and Hayashi and Nakano mass for star formation. In section 3 we review the basic (1963). -

Galactic Astronomy with AO: Nearby Star Clusters and Moving Groups

Galactic astronomy with AO: Nearby star clusters and moving groups T. J. Davidgea aDominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, BC Canada ABSTRACT Observations of Galactic star clusters and objects in nearby moving groups recorded with Adaptive Optics (AO) systems on Gemini South are discussed. These include observations of open and globular clusters with the GeMS system, and high Strehl L observations of the moving group member Sirius obtained with NICI. The latter data 2 fail to reveal a brown dwarf companion with a mass ≥ 0.02M in an 18 × 18 arcsec area around Sirius A. Potential future directions for AO studies of nearby star clusters and groups with systems on large telescopes are also presented. Keywords: Adaptive optics, Open clusters: individual (Haffner 16, NGC 3105), Globular Clusters: individual (NGC 1851), stars: individual (Sirius) 1. STAR CLUSTERS AND THE GALAXY Deep surveys of star-forming regions have revealed that stars do not form in isolation, but instead form in clusters or loose groups (e.g. Ref. 25). This is a somewhat surprising result given that most stars in the Galaxy and nearby galaxies are not seen to be in obvious clusters (e.g. Ref. 31). This apparent contradiction can be reconciled if clusters tend to be short-lived. In fact, the pace of cluster destruction has been measured to be roughly an order of magnitude per decade in age (Ref. 17), indicating that the vast majority of clusters have lifespans that are only a modest fraction of the dynamical crossing-time of the Galactic disk. Clusters likely disperse in response to sudden changes in mass driven by supernovae and stellar winds (e.g. -

Dwarfs Walking in a Row the filamentary Nature of the NGC 3109 Association

A&A 559, L11 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322744 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor Dwarfs walking in a row The filamentary nature of the NGC 3109 association M. Bellazzini1, T. Oosterloo2;3, F. Fraternali4;3, and G. Beccari5 1 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, via Ranzani 1, 40127 Bologna, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 3 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 4 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia - Università degli Studi di Bologna, viale Berti Pichat 6/2, 40127 Bologna, Italy 5 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei Munchen, Germany Received 24 September 2013 / Accepted 22 October 2013 ABSTRACT We re-consider the association of dwarf galaxies around NGC 3109, whose known members were NGC 3109, Antlia, Sextans A, and Sextans B, based on a new updated list of nearby galaxies and the most recent data. We find that the original members of the NGC 3109 association, together with the recently discovered and adjacent dwarf irregular Leo P, form a very tight and elongated configuration in space. All these galaxies lie within ∼100 kpc of a line that is '1070 kpc long, from one extreme (NGC 3109) to the other (Leo P), and they show a gradient in the Local Group standard of rest velocity with a total amplitude of 43 km s−1 Mpc−1, and a rms scatter of just 16.8 km s−1. It is shown that the reported configuration is exceptional given the known dwarf galaxies in the Local Group and its surroundings. -

The Formation and Early Evolution of Very Low-Mass Stars and Brown Dwarfs Held at ESO Headquarters, Garching, Germany, 11–14 October 2011

Astronomical News and spectroscopic surveys identifying the at the ELTs, together with encouraging emphasised the power of emerging coun- first galaxies, rare quasars, supernovae some explicitly high-risk projects. It was tries and public outreach for investments and gamma-ray bursts. noted that is very important to retain a in astronomical research and that diver- broad range of facilities, including sity in facilities and astronomical capabili- A lively discussion arose on data policy 4-metre- and 8-metre-class telescopes, ties should be retained together with and data mining for surveys and ELTs. to be used as survey facilities, to pro- large-scale projects. Ellis reminded us Most participants agreed that proprietary mote small projects, and to train young that we cannot plan the future in detail time should be at the minimum level but astronomers. All the long-term flagship and so optimism, versatility and creativity sufficient to guarantee intellectual owner- projects should try to involve more stu- remain the key attributes for success. ship and a satisfactory progress of the dents and young researchers, allowing surveys and the ELTs. Others proposed them to attend science working com- All the presentations and the conference to have the data public from the begin- mittees, and communicating the outcome picture are available at the conference ning. In order to facilitate data mining, it of the major high-level decisional meet- website: http://www.eso.org/sci/meetings/ was proposed that all data provided by ings to them. Furthermore, it was pro- 2011/feedgiant. the surveys and the ELTs should be Vir- posed that at least one young astrono- tual Observatory compliant from the out- mer should be included in each of the set. -

AST301 the Lives of the Stars

AST301 The Lives of the Stars A Tale of Two Forces: Pressure vs Gravity I. The Sun as a Star What we know about the Sun •Angular Diameter: q = 32 arcmin (from observations) •Solar Constant: f = 1.4 x 106 erg/sec/cm2 (from observations) •Distance: d = 1.5 x 108 km (1 AU). (from Kepler's Third Law and the trigonometric parallax of Venus) •Luminosity: L = 4 x 1033 erg/s. (from the inverse-square law: L = 4p d2 f) •Radius: R = 7 x 105 km. (from geometry: R = p d) •Mass: M = 2 x 1033 gm. (from Newton's version of Kepler's Third Law, M = (4p2/G) d3/P2) •Temperature: T = 5800 K. (from the black body law: L = 4pR2 σ T4) •Composition: about 74% Hydrogen, 24% Helium, and 2% everything else (by mass). (from spectroscopy) What Makes the Sun Shine? Inside the Sun Far Side Gary Larson Possible Sources of Sunlight • Chemical combustion – A Sun made of C+O: 4000 years • Gravitational Contraction – Convert gravitational potential energy – T = U/L = GM82R8/L8 ~ 107 years • Accretion – Limitless, but M8 increases 3% / 106 years • Nuclear Fusion – Good for ~1010 years How Fusion Works E=mc2 • 4 H ⇒ He4 + energy • The mass of 4 H atoms exceeds the mass of a He atom by 0.7%. • Every second, the Sun converts 6x108 tons of H into 5.96x108 tons of He. • The Sun loses 4x106 tons of mass every second. • At this rate, the Sun can maintain its present luminosity for about 1011 years. • 1010 or 1011 years ??? Nuclear Fusion Proton-Proton (PP I) reaction Releases 26.7 MeV 10 < Tcore < 14 MK How Fusion Works Source: Wikipedia Beyond PP I PP II: dominates for 14 < Tcore < 23 MK • 3He + 4He ⇒ 7Be + g 7 - 7 • Be + e ⇒ Li + ne + g • 7Li +p+ ⇒ 24He + g • 16% of L8 PP III: dominates for Tcore > 23 MK • 3He + 4He ⇒ 7Be + g • 7Be + p+ ⇒ 8B + g 8 8 + • B ⇒ Be + e + ne • 8Be ⇒ 24He • 0.02% of L8 Nuclear Timescale • 1010 years • Sun has brightened by 30% in 4.5 Gyr • Photons take 105 – 106 yrs to diffuse out – Gamma-rays thermalize to optical photons How do we know? • The p-p reaction also produces neutrinos. -

Interactions and Forces

background sheet The Standard Model 2: Interactions and forces Force Interactions The Australian Curriculum refers to fundamental In any closed system a number of properties are forces, force-carrying particles and reactions between conserved. These include energy, momentum and particles. However in this resource we have chosen charge. Although the totals of each property are to use a terminology used by contemporary particle conserved, their distribution amongst components physicists, that of interactions. of a system can change. Whenever energy (or momentum, charge or any other conserved property) The difference between ‘force’ and ‘interaction’ is is redistributed amongst components of a system subtle, but significant. Understanding it helps make then an interaction has taken place. In other words, sense of this complex study area. interactions lead to redistribution of energy, Students were probably introduced to the topic momentum and charge. of force through ‘pushes and pulls’. They learnt In Figure 1 two particles change their motion as they that changes to an object’s motion didn’t happen approach. There has been an exchange of energy and spontaneously, but were the result of some external momentum between them, so an interaction has taken action: a push or a pull. place. In this case the interaction is a consequence Later on these ideas were codified in Newton’s laws of these particles having charge, so the interaction is of motion. Together with Newton’s universal law described as electromagnetic. of gravitation, and Coulomb’s law of electrostatic Physicists recognise four fundamental interactions: interaction, changes in motion of objects could be seen as a consequence of force-pairs (action and reaction) • gravitational interaction acting between two objects. -

Stellar Evolution

Stellar Astrophysics: Stellar Evolution 1 Stellar Evolution Update date: December 14, 2010 With the understanding of the basic physical processes in stars, we now proceed to study their evolution. In particular, we will focus on discussing how such processes are related to key characteristics seen in the HRD. 1 Star Formation From the virial theorem, 2E = −Ω, we have Z M 3kT M GMr = dMr (1) µmA 0 r for the hydrostatic equilibrium of a gas sphere with a total mass M. Assuming that the density is constant, the right side of the equation is 3=5(GM 2=R). If the left side is smaller than the right side, the cloud would collapse. For the given chemical composition, ρ and T , this criterion gives the minimum mass (called Jeans mass) of the cloud to undergo a gravitational collapse: 3 1=2 5kT 3=2 M > MJ ≡ : (2) 4πρ GµmA 5 For typical temperatures and densities of large molecular clouds, MJ ∼ 10 M with −1=2 a collapse time scale of tff ≈ (Gρ) . Such mass clouds may be formed in spiral density waves and other density perturbations (e.g., caused by the expansion of a supernova remnant or superbubble). What exactly happens during the collapse depends very much on the temperature evolution of the cloud. Initially, the cooling processes (due to molecular and dust radiation) are very efficient. If the cooling time scale tcool is much shorter than tff , −1=2 the collapse is approximately isothermal. As MJ / ρ decreases, inhomogeneities with mass larger than the actual MJ will collapse by themselves with their local tff , different from the initial tff of the whole cloud. -

Galaxies: Outstanding Problems and Instrumental Prospects for the Coming Decade (A Review)* T (Cosmology/History of Astronomy/Quasars/Space) JEREMIAH P

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 74, No. 5, pp. 1767-1774, May 1977 Astronomy Galaxies: Outstanding problems and instrumental prospects for the coming decade (A Review)* t (cosmology/history of astronomy/quasars/space) JEREMIAH P. OSTRIKER Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 Contributed by Jeremiah P. Ostriker, February 3, 1977 ABSTRACT After a review of the discovery of external It is more than a little astonishing that in the early part of this galaxies and the early classification of these enormous aggre- century it was the prevailing scientific view that man lived in gates of stars into visually recognizable types, a new classifi- a universe centered about himself; by 1920 the sun's newly cation scheme is suggested based on a measurable physical quantity, the luminosity of the spheroidal component. It is ar- discovered, slightly off-center position was still controversial. gued that the new one-parameter scheme may correlate well The discovery was, ironically, due to Shapley. both with existing descriptive labels and with underlying A little background to this debate may be useful. The Island physical reality. Universe hypothesis was not new, having been proposed 170 Two particular problems in extragalactic research are isolated years previously by the English astronomer, Thomas Wright as currently most fundamental. (i) A significant fraction of the (2), and developed with remarkably prescience by Emmanuel energy emitted by active galaxies (approximately 1% of all galaxies) is emitted by very small central regions largely in parts Kant, who wrote (see refs. 10 and 23 in ref. 3) in 1755 (in a of the spectrum (microwave, infrared, ultraviolet and x-ray translation from Edwin Hubble). -

Probing the Quantum Universe )

July06-final.qxd 9/20/2006 9:29 PM Page 185 ARTICLE DE FOND ( PROBING THE QUANTUM UNIVERSE ) PROBING THE QUANTUM UNIVERSE by Alain Bellerive This article summarizes the activities encompassed by the the composition of our Universe, and the understanding of Particle Physics Division (PPD) at the 2006 Canadian elementary particle properties. The on-going Canadian par- Association of Physicists (CAP) annual congress that took ticipation in CLEO-c, ZEUS, D0 and CDF projects are paving place at Brock University. The summary is targeted toward the road for understanding the physics awaiting our commu- the general readership of Physics in Canada as it is meant to nity at the LHC. The knowledge gained by the future ILC be a review for non-experts in the experiments and the upcoming LHC form of a comprehensive overview of experiments is complementary since the physics research at the subatomic both facilities are needed to develop a scale. In a way the ultimate goal of A comprehensive summary more complete theory of fundamental particle physics is to establish the link of the research topics in particles and interactions. The study between our Quantum Universe and of particle properties and the probable Cosmology, and the research innova- subatomic physics and a discovery of the constituents of dark tions proposed by the PPD are critical look at the future challenges matter at accelerator complexes is for advancing this mission. The con- tightly coupled to direct investigation nection between research in particle of the Particle Physics of weakly interacting particles with physics and cosmology has never Division (PPD).