Free Throws: Understanding Clutch Performance Under Pressure From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

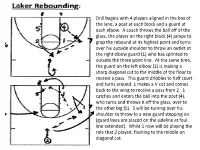

Drill Begins with 4 Players Aligned in the Box of the Lane, a Post at Each Block and a Guard at Each Elbow

Drill begins with 4 players aligned in the box of the lane, a post at each block and a guard at each elbow. A coach throws the ball off of the glass, the player on the right block (4) jumps to grap the rebound at its highest point and turns over his outside shoulder to throw an outlet ot the right elbow guard (1) who has sprinted to outside the three point line. At the same time, the guard on the left elbow (2) is making a sharp diagonal cut to the middle of the floor to receive a pass. This guard dribbles to half court and turns around. 1 makes a V cut and comes back to the wing to receive a pass from 2. 1 catches and enters the ball into the post (4), who turns and throws it off the glass, over to the other big (5). 5 will be turning over his shoulder to throw to a new guard stepping on (guard lines are placed on the sideline at foul line extended). While 1 now will be playing the role that 2 played, flashing to the middle on diagonal cut. Divide the team into three teams (A,B , and C) and have them line up as shown. The first player in line steps up and A has the ball. ‘A’ shoots a three. The ball is “live”, regardless of whether or not the shot is missed or made. (On a make the three doesn’t count). The game then becomes 1 on 1 on 1. With the player who grabbed the rebound being the one on offense. -

Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules

Princeton University Intramural Sports Floor Hockey Rules I. EQUIPMENT/UNIFORM/ELIGIBILITY a. All players must present their Princeton University ID in order to participate. b. The Intramural Department will provide sticks and balls. c. Players may wear gloves/mittens for hand protection. d. Each player must wear non-marking athletic shoes. e. Players may not wear hats with brims or jewelry during play. f. Goalies MUST wear a regulation catcher’s mask/goalie mask and chest protector, which are provided, if a goalie chooses to wear their own mask – it must be inspected by IM Supervisor before game begins. g. Goalies may wear a baseball glove on their non-stick hand and leg pads. h. All players must play in at least ONE regular season game in order to be eligible for playoffs. i. Players can only play for ONE Open/Women’s and/or ONE CoRec Team. j. Men’s and Women’s varsity Ice Hockey players and varsity Field Hockey players are not eligible. k. Only 2 Ice Hockey/Field Hockey Club players or 2 Junior Varsity players (or combination of the 2) are eligible to be on a team’s roster. II. NUMBER OF PLAYERS/GAME TIME/FORFEIT PENALTY a. Teams consist of 5 players on the floor at one time, four offensive players and a goalie. b. A minimum of 4 players is required to start and continue a game. c. For CoRec, the gender ratio is 3:2 with five players; and 2:2 with four players. d. A team that fails to have 4 players within 10 minutes after the start time of the game will forfeit/default the game. -

Praise for Everyone Hates a Ball Hog but They All Love a Scorer

Praise for Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer “Coach Godwin's book offers a complete guide to being a team player, both on and off the court.” --Stack Magazine “Coach Godwin's book gives you insight on how to improve your game. If you are a young player trying to get better, this is a book I would recommend reading immediately.” --Clifford Warren, Head Coach Jacksonville University “Coach Godwin explains in understandable terms how to improve your game. A must have for any young player hoping to get to the next level.” --Khalid Salaam, Senior Editor, SLAM Magazine “I wish that I had this book when I was 16. I would have been a different and better player. Well done.” --Jeff Haefner, Co-owner, BreakthroughBasketball.com “The entire book is filled with gems, some new, some revised and some borrowed, but if you want to read one book this year on how to become a better scorer this is the book.” --Jerome Green, Hoopmasters.org “Detailed instruction on how to score, preaching that the game is more mental than physical. Good reading for the young set, who might put down that joystick for a few hours.” --CharlotteObserver.com Everyone Hates A Ball Hog But They All Love A Scorer ____________________________________________ The Complete Guide to Scoring Points On and Off the Basketball Court Coach Koran Godwin This book is dedicated to my mother, Rhonda who supported me every step of the way. Thanks for planting the seeds of success in my life. I am forever grateful. -

Official Basketball Statistics Rules Basic Interpretations

Official Basketball Statistics Rules With Approved Rulings and Interpretations (Throughout this manual, Team A players have last names starting with “A” the shooter tries to control and shoot the ball in the and Team B players have last names starting with “B.”) same motion with not enough time to get into a nor- mal shooting position (squared up to the basket). Article 2. A field goal made (FGM) is credited to a play- Basic Interpretations er any time a FGA by the player results in the goal being (Indicated as “B.I.” references throughout manual.) counted or results in an awarded score of two (or three) points except when the field goal is the result of a defen- sive player tipping the ball in the offensive basket. 1. APPROVED RULING—Approved rulings (indicated as A.R.s) are designed to interpret the spirit of the applica- Related rules in the NCAA Men’s and Women’s Basketball tion of the Official Basketball Rules. A thorough under- Rules and Interpretations: standing of the rules is essential to understanding and (1) 4-33: Definition of “Goal” applying the statistics rules in this manual. (2) 4-49.2: Definition of “Penalty for Violation” (3) 4-69: Definition of “Try for Field Goal” and definition of 2. STATISTICIAN’S JOB—The statistician’s responsibility is “Act of Shooting” to judge only what has happened, not to speculate as (4) 4-73: Definition of “Violation” to what would have happened. The statistician should (5) 5-1: “Scoring” not decide who would have gotten the rebound if it had (6) 9-16: “Basket Interference and Goaltending” not been for the foul. -

Basketball House Rules

Policy and Procedure Department: Recreation + Wellness Section: Title: Kiewit Fitness Center Basketball House Effective Date: Rules Authored by: Lucia Zamecnik Approval Date: Approved by: Revision Date: Type: Departmental Policy Purpose: This policy was created to ensure the general safety of all patrons who are planning on participating in basketball within the Kiewit Fitness Center and to provide a general outline of what is expected of those participating. Scope: All students, faculty, staff and guests that are using the recreational facilities that are planning on participating in pick up basketball. Policy: Follow all guidelines associated with basketball games in the Kiewit Fitness Center in the procedure section below. Failure to follow guidelines will result in suspension or facility privileges being revoked. Procedure/Guidelines: Team Selection – First Game of the day on each court only: 1. Teams for the first game of the day on each court are determined by shooting free throws. Players may not select their own teams 2. The first five people to score form one team. The next five people form the second team. Everyone must get an equal number of chances to shoot. If free throw shooting takes too long, players will move to the three-point line to shoot. 3. After teams are selected, a player from either team will take a three-point shot. If it goes in, that team take the opening in-bound. Otherwise, the other team receives the in-bound to start the game. 4. Teams are formed on a first-come, first-serve basis. 5. Whoever has called the net game will accept the next four people who arrive at that court and ask to play 6. -

Protecting the Free Thrower

Protecting the Free Thrower Rule 9-1-3g was revised in 2014-15 to allow a player occupying a marked lane space to enter the lane on the release of the ball by the free thrower. As a result of this change, protection of the free thrower needs to be emphasized. On release of the ball by the free thrower, the defender boxing out shall not touch or cross the free-throw line extended into the semicircle until the ball contacts the ring or backboard. A player, other than the free thrower, who does not occupy a marked lane space, may not have either foot beyond the vertical plane of the free-throw line extended and the three-point line which is farther from the basket until the ball touches the ring or backboard or until the free throw ends. Only the free thrower is allowed in the semi-circle until the ball is released and touches the ring or the backboard. The free-throw shooter is the only player allowed in the semicircle prior to the ball contacting the ring or backboard. Players outside marked lane spaces, including the free-throw shooter, cannot enter the lane spaces until the ball contacts the ring or backboard. 10/27/15 From Mark Preseason Guide Article “Enforce Illegal Contact on Free Thrower and Violations During Free Throw”, page 6, second paragraph: 10/27/15 From Mark The free thrower must remain within the free throw semi-circle until the ball contacts the backboard or the rim. The same rule applies to all other players who do not occupy free throw lane line spaces. -

Referee.Com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51

Referee.com Basketball Case Play of the Day Day 51- Disqualified Player PLAY A1 is called for a common foul, and it is A5’s fifth personal foul. A1 properly leaves the game after receiving this fifth and disqualifying foul. Later in the game, A1 reports to the table to check back into the game. Neither the official scorer nor the officials recognize that A1 had previously been disqualified, and they allow A1 to re-enter the game. After a few minutes have run off the game clock and (a) after A1 had checked back out of the game, or (b) while A1 is still in the game, the scorer notifies the officials that A1 had been disqualified, but participated again in the game. What is the result? RULING Participating after being disqualified results in a technical foul. The technical foul is only penalized if it is discovered while being violated. Therefore, in (a), since A1 was no longer in the game, no technical foul shall be assessed. In (b), a technical foul shall be charged directly to team A’s head coach, A1 shall be removed from the game, team B shall receive two free throws and a division line throw in (10-6-3, 10.6.3). Day 50- Colors of Team Apparel PLAY Team A is wearing blue jerseys with gold trim. During pregame warmups, the officials notice A1 is wearing a black undershirt, blue wristbands and gold tights. Are those colors legal? RULING The color of the undershirt must be a single color similar to the torso of the game jersey, and thus a black undershirt is not legal. -

Fiba Glossary.Pdf

Glossary Basketball Glossary A Advance step: A step in which the defender's lead foot steps toward their man, and her back foot slides forward. Assist: A pass thrown to a player who immediately scores. B Backcourt: The half of the court a team is defending. The opposite of the frontcourt. Also used to describe parts of a team: backcourt = all guards (front court= all forwards and centers) Back cut: See cuts, Backdoor cut Backdoor cut: See cuts Back screen: See Screens Ball fake: A sudden movement by the player with the ball intended to cause the defender to move in one direction, allowing the passer to pass in another direction. Also called "pass fake." Ball reversal: Passing the ball from one side of the court to the other. Ball screen: See Screens Ball side: The half of the court (if the court is divided lengthwise) that the ball is on. Also called the "strong side." The opposite of the help side. Banana cut: See cuts Bank shot: A shot that hits the backboard before hitting the rim or going through the net. Baseball pass: A one-handed pass thrown like a baseball. Baseline: The line that marks the playing boundary at each end of the court. Also called the "end line." Baseline out-of-bounds play: The play used to return the ball to the court from outside the baseline along the opponent's basket. Basket cut: See cuts. Blindside screen: See Backscreen Glossary Block: (1) A violation in which a defender steps in front of a dribbler but is still moving when they collide. -

Research on Free Throw Shooting Skills in Basketball Games

[Type text] ISSN : [Type0974 -text] 7435 Volume 10[Type Issue text] 20 2014 BioTechnology An Indian Journal FULL PAPER BTAIJ, 10(20), 2014 [11799-11805] Research on free throw shooting skills in basketball games Xiangkun Yang Department of Physical Education, Jingchu University of Technology, JingMen 448000, (CHINA) ABSTRACT This study makes modeling research on key skills of free throw in basketball games, which are of great significance for enhancing the capacity of free throws. By curvilinear motion model assumptions, three shots models are set up; by model analysis, more accurate idea of free throw shooting is proposed and basketball free throw motion track is studied; by continuously enhancing free throw shooting skills, the accuracy of free throw is improved. KEYWORDS Basketball games; Free throw shooting skills; Modeling. © Trade Science Inc. 11800 Research on free throw shooting skills in basketball games BTAIJ, 10(20) 2014 INTRODUCTION In basketball games, free throw shooting is one of the most basic techniques, and one or two scores made by free throws often can determine the outcome of the game. In America's NBA and in China's CBA games, it is often seen that a team would lose the match just because of one or two scores. The famous Hack-a-Shaq is used against players who are bad at free throws, so you can make the other side get the lowest chance of scoring and make the ball in your possession. It is often seen in the last few minutes of the Professional Basketball League game that the team with lower scores may use Hack-a- Shaq against the player in the other team who are bad at free throws, so the team with lower scores will greatly increase the chance to win. -

NCAA and NFHS Major Basketball Rules Differences

2020-21 MAJOR BASKETBALL RULES DIFFERENCES (Men’s and Women’s) ITEM NFHS NCAA Administrative Warnings Issued for non-major infractions of coaching- Men – Only for the head coach being outside the box rule, disrespectfully addressing an official, coaching box and certain delay-of-game situations. attempting to influence an official’s decision, Women – Same as Men plus minor conduct inciting undesirable crowd reactions, entering violations of misconduct guidelines by any bench the court without permission, or standing at the personnel. team bench. Bonus Free Throws One-and-One Bonus On the seventh team foul. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – No one-and-one bonus. Double Bonus On the 10th team foul. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – On fifth team foul. Team Fouls Reset End of the first half. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – End of first, second and third periods. Blood/Contacts Player with blood directed to leave game (may Men – Player with blood may remain in game if remain in game with charged time-out); player remedied within 20 seconds. Lost/irritated contact with lost/irritated contacts may remain in game within reasonable time. with reasonable time to correct. Women – Player with may remain in game if remedied within 20 seconds or charged timeout to correct blood or contacts. Coaching Box Size State option, 28-foot box maximum. Both – Extends from 38-foot line to end line. Loss of Use If head coach is charged with a direct or indirect Both – No rule. technical foul. Delay-of-Game Warnings One warning for any of the four delay-of-game Men – One warning for any of the four delay-of- situations; subsequent delay for any of four game situations; a repeated warning for the same results in a technical foul. -

Basketball Knockout RULES

Basketball knockout RULES: ● The game begins with all players lined up in a straight line starting at the free throw line and extending towards half court (see diagram #1). The first two players start with a basketball. ● Player one shoots a free throw and tries to make it. If the player misses, he/she must grab the rebound and score as fast as possible. Player one’s second shot does not need to be from the free throw line. He/she can shoot a jump shot, lay-up or whatever is needed in order to score fastest. ● Player two cannot shoot until after player one has shot their first free throw. The goal for player two is to score a basket before player one does. If player two misses their free throw he/she must also rebound their miss and make a shot as quickly as possible. ● If player one makes a basket first, he/she goes to the back of the line (see diagram #2). If player one fails to make a basket before player two, player one is eliminated (all eliminated players stand off to the side until the game is finished). ● Once player one makes a basket he/she passes the ball to the next player in line. That player tries to make a basket before player two does. If this occurs, player two is out. If player two scores first, he/she goes to the end of the line and passes their ball to the fourth player in line (see diagram #3). ● The game continues like this until only one player is left standing. -

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams

Analyzing the Influence of Player Tracking Statistics on Winning Basketball Teams Igor Stan čin * and Alan Jovi ć* * University of Zagreb Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing / Department of Electronics, Microelectronics, Computer and Intelligent Systems, Unska 3, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - Basketball player tracking and hustle statistics year at the Olympic games, by winning a gold medal in the became available since 2013-2014 season from National majority of cases. Off the court, there are specialized Basketball Association (NBA), USA. These statistics provided personnel who try to improve each segment of the game, us with more detailed information about the played games. e.g. doctors, psychologists, basketball experts and scouts. In this paper, we analyze statistically significant differences One of the most interesting facts is that the teams in the in these recent statistical categories between winning and losing teams. The main goal is to identify the most significant league, and the league itself, have expert teams for data differences and thus obtain new insight about what it usually analysis that provide them with valuable information about may take to be a winner. The analysis is done on three every segment of the game. There are a few teams who different scales: marking a winner in each game as a winning make all of their decisions exclusively based on advanced team, marking teams with 50 or more wins at the end of the analysis of statistics. Few years ago, this part of season as a winning team, and marking teams with 50 or organization became even more important, because NBA more wins in a season, but considering only their winning invested into a computer vision system that collects games, as a winning team.