Creating Successful Transit- Oriented Districts in Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

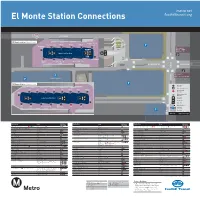

El Monte Station Connections Foothilltransit.Org

metro.net El Monte Station Connections foothilltransit.org BUSWAY 10 Greyhound Foothill Transit El Monte Station Upper Level FT Silver Streak Discharge Only FT486 FT488 FT492 Eastbound Metro ExpressLanes Walk-in Center Discharge 24 25 26 27 28 Only Bus stop for: 23 EMT Red, EMT Green EMS Civic Ctr Main Entrance Upper Level Bus Bays for All Service B 29 22 21 20 19 18 Greyhound FT481 FT Silver Streak Metro Silver Line Metro Bike Hub FT494 Westbound RAMONA BL RAMONA BL A Bus stop for: EMS Flair Park (am/pm) Metro Parking Structure Division 9 Building SANTA ANITA AV El Monte Station Lower Level 1 Bus Bay A Bus Stop (on street) 267 268 487 190 194 FT178 FT269 FT282 2 Metro Rapid 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bus Bay 577X Metro Silver Line 8 18 Bus Bay Lower Level Bus Bays Elevator 76 Escalator 17 Bike Rail 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 EMS Bike Parking 270 176 Discharge Only Commuter 770 70 Connection Parking Building 13-0879 ©2012 LACMTA DEC 2012 Subject to Change Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Street Stop Street Stop Street Stop 7th St/Metro Center Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Hacienda Heights FT282 16 Pershing Square Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line , 70, 76, 770, 1 2 17 18 37th St/USC Transitway Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 FT Silver Streak 19 20 21 Harbor Fwy Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Pomona TransCenter ÅÍ FT Silver Streak 28 Alhambra 76, 176 6 17 Highland Park 176 6 Altadena 267, 268 9 10 Puente Hills Mall FT178, FT282 14 16 Industry Å 194, FT282 13 16 Arcadia 268, -

West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor

Item 6 Eco-Rapid Transit, formerly known as the Orangeline A G E N D A R E P O R T Development Authority, is a joint powers authority (JPA) created to pursue development of a transit system that moves as rapidly as TO: Members of Eco-Rapid Transit possible, uses grade separation as appropriate, and is environmentally friendly and FROM: Michael Kodama, Executive Director energy efficient. The system is designed to enhance and increase transportation options for riders of this region utilizing safe, DATE: October 14, 2015 advanced transit technology to expand economic growth that maximizes ridership in Southern SUBJECT: UPDATE AND/OR ACTION REGARDING WEST SANTA ANA BRANCH California. The Authority is composed of the TECHNICAL REFINEMENT STUDY AND PRESENTATION BY METRO STAFF following public agencies: ISSUE City of Artesia City of Bell The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (METRO) Board of Directors approved its consultant final report on the West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB). City of Bell Gardens Chair Maria Davila and others attended the September 16, 2015 Metro Planning and City of Bellflower Programming Committee meeting on behalf of Eco-Rapid Transit. City of Cudahy City of Downey Metro staff (Renee Berlin and Fanny Pan) will provide an update to the Board of City of Glendale Directors. City of Huntington Park City of Maywood DISCUSSION City of Paramount The Pacific Electric West Santa Ana Branch is an important part of the proposed Eco- City of South Gate Rapid Transit Corridor transit improvement program. This is what is considered the City of Vernon Southern Corridor of the transit services being planned by the Joint Powers Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Authority. -

Los Angeles Orange Line

Metro Orange Line BRT Project Evaluation OCTOBER 2011 FTA Report No. 0004 Federal Transit Administration PREPARED BY Jennifer Flynn, Research Associate Cheryl Thole, Research Associate Victoria Perk, Senior Research Associate Joseph Samus, Graduate Research Assistant Caleb Van Nostrand, Graduate Research Assistant National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Center for Urban Transportation Research University of South Florida CCOOVVEERR PPHHOTOOTO LLooss AAnnggeelleess CCoouunnttyy MMeettrrooppololiittanan TTransransppoorrttaattioionn AAuutthhoorriittyy DDIISCSCLLAAIIMMEERR TThhiis ds dooccuumemennt it is is inntteennddeed ad as a ts teecchhnniiccaal al assssiissttaanncce pe prroodduucctt. I. It it is dsiiss ssdeemmiinnaatteed udnn ddueer tr thhe sepp oosnnssoorrsshhiip opf tf tohhe Ue..SS U.. DDeeppaarrttmemennt ot of Tf Trraannssppoorrttaattiioon in in tn thhe ie inntteerreesst ot of if innffoorrmamattiioon enxxcc ehhaannggee. T. Thhe Uenn iittUeed Sdttaa Sttees Gsoo vvGeerrnnmemennt atss ssauumemes nso nlo liiaabbiilliittyy ffoor ir itts cs coonntteenntts os or ur usse te thheerreeooff. T. Thhe Ue Unniitteed Sd Sttaattees Gs Goovveerrnnmemennt dtoo eeds nsoo tn et ennddoorrsse perroo pdduucctts osf mfo aa nnmuuffaaccttuurreerrss. T. Trraadde oerr o mamannuuffaaccttuurreerrss’ n’ naamemes as appppeeaar her herreeiin sn soolleelly by beeccaauusse te thheey ayrre a ceoo nncssiiddeerreed edssss eeennttiiaal tl to tohh et oebb jjeeoccttiivve oef tf tohhiis rs reeppoorrtt.. Metro Orange Line BRT Project Evaluation OCTOBER 2011 FTA Report No. 0004 PREPARED BY Jennifer Flynn, Research Associate Cheryl Thole, Research Associate Victoria Perk, Senior Research Associate Joseph Samus, Graduate Research Assistant Caleb Van Nostrand, Graduate Research Assistant National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Center for Urban Transportation Research University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, CUT100 Tampa, FL 33620 SPONSORED BY Federal Transit Administration Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation U.S. -

Victory Blvd up to 60% Seller Financing Available for Two Years Canoga Park, Ca

±1.51 ACRE MULTIFAMILY MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT SITE UP TO 4.5:1 FAR LOCATED IN WARNER CENTER SPECIFIC PLAN EXISTING IN-PLACE INCOME 21161VICTORY BLVD UP TO 60% SELLER FINANCING AVAILABLE FOR TWO YEARS CANOGA PARK, CA Royal Orchid Flooky’s Ferguson Bath, Kitchen & CANOGA AVE Lighting Gallery 21161 Zoo Culture VICTORY BLVD The Pampered Pet Hotel & Spa U-Haul DE SOTO AVE VICTORY BLVD KITTRIDGE ST Laurie Lustig-Bower Kamran Paydar Executive Vice President Vice President +1 310 550 2556 +1 310 550 2529 [email protected] [email protected] www.21161Victory.com Lic. 00979360 Lic. 01242590 CANOGA PARK BOB HOPE 405 AIRPORTT 21161 RESEDA VICTORY BLVD NORTH VAN NUYS HOLLYWOOD WOODLAND 170 BURBANK HILLS ENCINO 134 SHERMAN OAKS GLENDALE UNIVERSAL CITY GRIFFITH 27 OBSERVATORY HIGHLAND PARK TOPANGA BEL AIR LOS FELIZ STATE PARK HOLLYWOOD WEST HOLLYWOOD 405 ECHO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BEVERLY HILLS PARK LOS ANGELES KOREATOWN CHINATOWN MID-WILSHIRE CENTURY CITY BRENTWOOD PICO UNION DOWNTOWN PACIFIC LOS ANGELES PALISADES SANTA UNIVERSITY OF MONICA CULVER CITY SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CRENSHAW MAR VISTA KENNETH HAHN STATE LEIMERT PARK RECREATION AREA VERNON 405 SOUTH LOS ANGELES VENICE HUNTINGTON MARINA PARK PACIFIC DEL REY OCEAN INGLEWOOD PLAYA DEL REY SOUTH GATE LAX 2 | www.21161Victory.com © 2019 CBRE Limited. Data © TeleAtlas, Google, AerialExpress, DigitalGlobe, Landiscor, USGS, i-cubed. The information contained herein (the “Information”) is intended for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon by recipients hereof. Although the Information is believed to be correct, its accuracy, correctness or completeness cannot be guaranteed and has not been verified by either CBRE Limited or any of its affiliates (CBRE Limited and its affiliates are collectively referred to herein as “CBRE”). -

January 2015

metro.net Metro Orange Line Connections h s a W h s a a Hansen Dam n DEVONSHIRE ST DEVONSHIRE ST DEVONSHIRE ST 5 a W s u r S Chatsworth Station u a lb t i ARLETA AVG Metro Rapid Stop n 405 W W O a Chatsworth Station L S O D METROLINK GLENOAKS BL O E LAUREL CYN BL D Metro Rapid Line TOPANGA CYN BL CYN TOPANGA TOPANGA CYN BL CYN TOPANGA N M LASSEN ST LASSEN ST LASSEN ST A N S Metro Orange Line T SAN FERNANDO RD CHATSWORTH A A T Station VA V E TAMPA AV TAMPA Sepulveda Metro Orange Line CORBIN AV ZELZAH AV F WILBUR AV RESEDA BL RESEDA PLUMMER ST PLUMMER ST PLUMMER BL BALBOA ST PLUMMER ST ARLETA W DE SOTO AV DE SOTO WOODLEY AV WOODLEY Y WINNETKA AV SEPULVEDA BL SEPULVEDA Metro Rail Station VINCENNES ST TERRA BELLA ST Northridge East CanyonARLETA Channel AV SUN AMTRAK/METROLINK 27 Fashion CSUN NORTH HILLS VALLEY Metro Red Line Center NORTHRIDGE NORDHOFF ST AV DARBY NORDHOFF ST NORDHOFF ST OSBORNE ST Transfers SAN DIEGO FWY Nordhoff Station Metrolink h SHELDON ST NORDHOFF ST Northridge Station s a PANORAMA W Amtrak 5 Bull Creek BRANFORD ST PARTHENIA ST PARTHENIA ST PARTHENIA ST CITY Parking a 15-0989 ©2014 LACMTA m H WEST HILLS i o CHASE ST O DEC 2014 Subject to Change c L a L P ROSCOE BL Roscoe Station ROSCOE BL ROSCOE BL Y W TUXFORD ST O O Sun Valley Station METROLINK D Aliso Canyon Wash Aliso Canyon SAN FERNANDO RD STRATHERN ST STRATHERN ST F STRATHERN ST W Y DE SOTO AV DE SOTO Van Nuys Station Tujunga Wash FlyAway WHITSETT AV Bus Terminal NUYS BL VAN WHITE OAK AV WHITE OAK TAMPA AV TAMPA VARIEL AV VARIEL WOODLAKE AV WOODLAKE WOODLAKE AV -

LA Metro and Transit-Oriented Communities: Creating Equitable Planning Practices Through Community Engagement at Mariachi Plaza

LA Metro and Transit-Oriented Communities: Creating Equitable Planning Practices through Community Engagement at Mariachi Plaza Michael Jiménez Spring 2018 Senior Comprehensive Thesis Professors Shamasunder and Cha Submitted for the consideration of a BA in Urban and Environmental Policy Occidental College Jiménez !2 Table of Contents Introduction….4 Background….5 Boyle Heights and Metro….5 Metro Joint Development and Mariachi Plaza….6 The Fight for Boyle Heights….7 Literature Review….10 Community Engagement and Spatial Justice….10 Modeling Participatory Planning….12 Transit Dependence….13 Race, Transit-Riders, and Equitable Development….15 TOD and the Risk for Displacement….16 Cases for Community Engagement and Participatory Planning….18 i. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Participatory Planning for Effective Urban Regeneration ii. Community Planning at Metro: Empowering Those in Need Methodology…22 Interview Design and Process….22 Policy Analysis….25 Limitations….25 Findings and Analysis….27 Introduction — Evaluating Metro Joint Development….27 Representation through Community Engagement….29 i. High Turnout, High Representation ii. Community Engagement Brings Mutual Benefits Metro’s Role for Community Engagement….31 i. Boyle Heights Between City and County — The Need to Create Local Routes ii. Accounting for Inequity: Improving Joint Development iii. Exclusive Negotiation: Informing Capacity Building and Realistic Planning Equity or Access to Opportunity?….38 i. Partnering for TOD Future Research….41 Recommendations….41 Transit….42 i. Update Metro’s Goals for Transit-Oriented Development Metro Accountability….43 i. The Role of the JD Administrator ii. Explicitly Define Capacity Building Community Organizing….45 Jiménez !3 i. Highlight the Fight for Boyle Heights Transparency….47 i. Develop Periodic Community Reports ii. -

Torrance Bus Service Reliability and Improvement Strategies

TORRANCE BUS SERVICE RELIABILITY AND IMPROVEMENT STRATEGIES A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master In Urban and Regional Planning By Jose M. Perez 2019 i SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: TORRANCE BUS SERVICE RELIABILITY AND IMPROVEMENT STRATEGIES AUTHOR: Jose M. Perez DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2019 Department of Urban and Regional Planning Dr. Alvaro M. Huerta Project Committee Chair Professor of Urban Planning Richard Zimmer Committee Member Lecturer of Urban Planning David Mach Senior Transportation Planner Torrance Transit i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author thanks the Torrance Transit Employees for the data they furnished and their participation in the client project, especially Senior Transportation Planner David Mach. The author would also like to thank the City of Torrance for providing information on future development and specific goals of their circulation plan. Special thanks to Dr. Alvaro M. Huerta and Professor Richard Zimmer for their help and guidance in completing the client project. i ABSTRACT A city’s transportation infrastructure directly affects the mobility of the people, goods, and services, of all who live within its’ limits. Bus transit lines are a key element of a balanced transportation system that can improve or detract from the quality of life of its’ populous. Transit networks that are poorly implemented eventually become impractical and difficult to maintain; and thus, a burden upon the city it’s meant to help. In addition the service reliability of a transit line is critical to both the transit agency and its users in order to maintain a healthy transportation system. -

West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor Project

Draft EIS/EIR Appendix F Final Safety and Security Impact Analysis Report WEST SANTA ANA BRANCH TRANSIT CORRIDOR PROJECT Draft EIS/EIR Appendix F Final Safety and Security Impact Analysis Report Prepared for: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Prepared by: WSP 444 South Flower Street Suite 800 Los Angeles, California 90071 July 2021 Authors AUTHORS Charlie Hetland, Jacobs John Simon, Jacobs Ryo Nagai, Jacobs Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Study Background ................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Alternatives Evaluation, Screening and Selection Process .................................... 1-1 1.3 Report Purpose and Structure .............................................................................. 1-2 1.4 General Background ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.4.1 Safety .................................................................................................... 1-3 1.4.2 Security ................................................................................................. 1-4 1.4.3 Impact Criteria and Thresholds ............................................................ 1-5 1.5 Methodology ........................................................................................................ 1-6 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................ -

Framework of Sustainable Transit Communities

FRAMEWORK OF SUSTAINABLE TRANSIT COMMUNITIES OFFICE OF THE MAYOR, CITY OF LOS ANGELES FEBRUARY 2011 This is a project for the City of Los Angeles (City) with funding provided by the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG) Compass Blueprint Program. Compass Blueprint assists Southern California cities and other organizations in evaluating planning options and stimulating development consistent with the region’s goals. Compass Blueprint tools support visioning efforts, infill analyses, and marketing and communications programs. The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) in accordance with the provision under the Metropolitan Planning Program as set forth in Section 104(f) of Title 23 of the U.S. Code. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author, who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of SCAG, DOT, or the State of California. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. SCAG shall not be responsible for the City’s future use or adaptation of the report. FRAMEWORK OF SUSTAINABLE TRANSIT COMMUNITIES OFFICE OF THE MAYOR, CITY OF LOS ANGELES FEBRUARY 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 OVERVIEW OF THE FRAMEWORK 4 Mix and Vitality of Uses 9 Well-Defined Sense of Place 11 Walkability and the Pedestrian Realm 14 Multimodal -

Art Guide a Tour of Metro’S Artwork Metro Commissions Artists to Create Engaging and Thought-Provoking Artworks to Make Your Journey More Inviting and Pleasurable

metro.net Art Guide A tour of Metro’s artwork Metro commissions artists to create engaging and thought-provoking artworks to make your journey more inviting and pleasurable. The artworks weave a multi-layered cultural tapestry that mirrors Los Angeles County’s rich contemporary and popular cultures. Established in 1989, the Metro Art program has commissioned over 250 artists for a wide variety of both temporary and permanent projects. explore Artists are selected through a peer review process with community input; all works are created especially for their transit related sites. This guide is intended to help you discover artworks throughout the Metro system. For more detailed information on the artwork and the artists, please visit metro.net/art. Artwork copyrighted, all rights reserved. Metro Lines and Transitways Metro Contents Art’s a Trip. Art’s a Trip Metro Environments Free Metro Rail Tours Tours are o=ered the >rst Saturday, > Thursdays – Meet at 7pm at Sunday and Thursday of each month. the street level entrance to the Metro Rail Metro Customer Center It’s free. It’s provocative. The tours are roundtrip and last Hollywood/Highland Metro l Metro Red Line Metro Vehicles It’s a great ride. approximately two hours. Rail Station. Union Station Bus Plaza l Metro Purple Line Tours for groups of 15 or more are > Saturdays – Meet at 10am at > Each tour is unique, visits l Metro Gold Line Metro Headquarters available by special arrangement. the street level entrance to the di=erent stations and is led Metro Division 3 Hollywood/Highland Metro by a member of the Metro Art l Metro Blue Line Call 213 .922.2738 for information Rail Station. -

Los Angeles Equity Maps Large.Ai

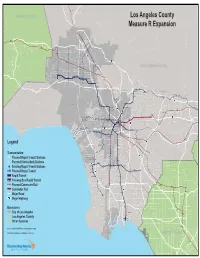

S and Can yo ! Newhall n Placerita Canyon Sand C any on Ventura County ra Los Angeles County er Si Th e Ol d Measure R Expansion l el rn Bradl ey Exi Ya d t 3 xfor Ro S lk an Fe Po d Big rnan T ujung do Hubbar n a Cany yo on sn SylmarSan Fernando on Se a ga Can Moorpark un ay Canyon mp ! cl uj ch T ! Ta Ma le Gl Litt Lopez Ran enoak er xton on Pa ce s er e Port Pi Rinaldi l Cany rn age bo HWY 118 and ys K Os San Fernando Mission Br ! an Nu V Simi Valley x on Chatsworth Fo Chatsworth Wentworth eas Ar le ta Devonshire Ar Mount Gl le ! boa ta Chatsworth and e ah Bal da rn unl Ma lz rilla oodley bo S INTERSTATE W Ze per la Os el Rese 5 Plummer B Sant Plummer a Plummer Ves rra a e Manor ed Te Carlotta Lak lv Nordhoff Ar Laur l Nordhoff epu heldon ! le S on Orange S ny ta el una Ca Fo C La T INTERSTATE othill Lowel o an ! d 210 a e Orange Line Extension ot anford yo or cl n xf ose Northridge Br ani Tu Honolul enr v De S P yl ey Cir u ll Roscoe Roscoe a W Rosc ! ! oe enns ka Va ebb ent P et Gl sc rch Sun Valley enoak Fo Van Nuys re othi Ma Winn ll im a s Los Angeles County Canoga San Fernando BRT Corridors S an ! La C sh oodlake Saticoy ed i nd cle Fe lv er W ir la rnando C ne epu Naom Lank ys ey Sherman Way Sherman S Vi Verdugo ll ! Sherman Glendora Ridge Va t Sc Fo rs k ot an Nu n ott hi V k Ramp ll oo yo an Alta a Burbank/ Bob Hope Airport den Oa Vanowen enhu San Ber a t De Soto ks Canoga ! e hi yv ! Empi Can re re mp it at Fallbr ! Gl Victory Woodley el Fe Pl Ha Ta ctory enoaks ! Vi Woodm d r K Wh ! ! Victory nan enne oo Reseda Laur do d -

Incentivizing Zero-Emission Vehicle Ride-Hail/Public Transit Commutes in Los Angeles

Incentivizing Zero-Emission Vehicle Ride-Hail/Public Transit Commutes in Los Angeles April 2018 By Juan M. Matute Herbie Huff Riley O’Brien Brian D. Taylor 1 Acknowledgements The research team received funding from the UCLA Sustainable Los Angeles Grand Challenge. From understanding future climate patterns and maximizing the region's solar potential, to understanding how gender plays a role in reducing our daily water use and revolutionizing plant and animal conservation management, we are spearheading the research necessary to define the region's pathway to sustainability. The research team also received support from the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies. The mission of the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies, one of the leading transportation policy research centers in the United States, is to support and advance cutting-edge research, the highest-quality education, and meaningful and influential civic engagement on the many pressing transportation issues facing our cities, state, nation, and world today. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 6 Project Research Objectives 6 Prior Research and Background 7 Transportation Network Companies 7 Overview 7 TNC-Transit Integration 10 Zero Emission Vehicles (ZEVs) Adoption 11 Clean Vehicle Adoption Overview 11 Plug-in hybrids and fully electric vehicles 11 Hydrogen fuel cell incentives 13 TNCs and ZEVs 13 Employee Commutes 13 Policy Setting and Background 14 State Policy Setting 14 Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 and 2016 Update 14 Governor’s Zero