What Is Scottish Literature?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reformation of the Pastoral Office Scott M. Manetsch EFCA One

The Reformation of the Pastoral Office Scott M. Manetsch EFCA One Conference New Orleans, July 1-3, 2013 LECTURE ONE: Pastors and their Vocation Introduction: The Use and Abuse of History - Antiquarians: The Assumption that Older is Better. - Presentists: The Assumption that Newer is Better. I. New Conceptions of the Pastoral Office (1) Protestants rejected the sacramental nature of Episcopal ordination. (2) Protestants challenged the Catholic teaching that priests dispensed salvific grace through the sacraments of the Church. (3) Protestant leaders rejected mandatory clerical celibacy. II. The Pastors’ New Job Description A. Introduction: B. Defining the Protestant Pastorate (1) Theological Surveys, Published Sermons, Biblical Commentaries: Reading #1: Guillaume Farel’s Summaire et Briefve Declaration (1529) (2) Church Constitutions and Church Orders: Reading #2: Geneva’s Ecclesiastical Ordinance (1541, 1561) (3) Liturgy and Prayers: Reading #3: Calvin’s La forme des priers et chantz ecclésiastiques (1542) (4) Private Instruction: Reading #4: Theodore Beza’s Letter to Louis Courant (1601) (5) Pastoral Handbooks: Heinrich Bullinger, Plan of Ministerial Studies (1528) Philip Melanchthon, On the Duties of the Preacher (1529) Andreas Hyperius, On the Formation of Sacred Sermons (1553) Martin Bucer, Concerning the True Care of Souls (1538) E.g. Bullinger’s Pastoral Job Description: Instruction (Doctrina): Teach sound doctrine; oversee moral life of the community; administer the sacraments; lead people in private and public prayers; provide catechetical instruction for children; care of the poor; visit the sick. Personal Conduct (Conversatio): Diligent in study; reputation for personal godliness; domestic life characterized by peace and harmony. Discussion: From the above readings, what are the most important spiritual qualities of a faithful pastor? What are the most important duties of a faithful pastor? What in this list surprised you? III. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

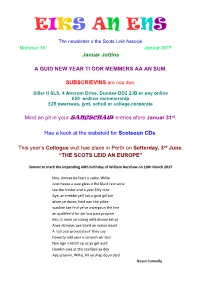

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

"Dae Scotsmen Dream O 'Lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 "Dae Scotsmen Dream o 'lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland Alexander Burke Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i © Alexander P. Burke 2013 All Rights Reserved i “Dae Scotsmen Dream o ‘lectric Leids?” Robert Crawford’s Cyborg Scotland A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English at Virginia Commonwealth University By Alexander Powell Burke Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University May 2011 Director: Dr. David Latané Associate Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2013 ii Acknowledgment I am forever indebted to the VCU English Department for providing me with a challenging and engaging education, and its faculty for making that experience enjoyable. It is difficult to single out only several among my professors, but I would like to acknowledge David Wojahn and Dr. Marcel Cornis-Pope for not only sitting on my thesis committee and giving me wonderful advice that I probably could have followed more closely, but for their role years prior of inspiring me to further pursue poetry and theory, respectively. -

On the Study and Promotion of Drama in Scottish Gaelic Sìm Innes

Editorial: On the study and promotion of drama in Scottish Gaelic Sìm Innes (University of Glasgow) and Michelle Macleod (University of Aberdeen), Guest-Editors We are very grateful to the editors of the International Journal of Scottish Theatre and Screen for allowing us the opportunity to guest-edit a special volume about Gaelic drama. The invitation came after we had organised two panels on Gaelic drama at the biennial Gaelic studies conference, Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig, at the University Edinburgh 2014. We asked the contributors to those two panels to consider developing their papers and submit them to peer review for this special edition: each paper was read by both a Gaelic scholar and a theatre scholar and we are grateful to them for their insight and contributions. Together the six scholarly essays and one forum interview in this issue are the single biggest published work on Gaelic drama to date and go some way to highlighting the importance of this genre within Gaelic society. In 2007 Michelle Macleod and Moray Watson noted that ‘few studies of modern Gaelic drama’ (Macleod and Watson 2007: 280) exist (prior to that its sum total was an unpublished MSc dissertation by Antoinette Butler in 1994 and occasional reviews): Macleod continued to make the case in her axiomatically entitled work ‘Gaelic Drama: The Forgotten Genre in Gaelic Literary Studies’. (Dymock and McLeod 2011) More recently scholarship on Gaelic drama has begun to emerge and show, despite the fact that it had hitherto been largely neglected in academic criticism, that there is much to be gained from in-depth study of the genre. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

Concerts & Castles

Concerts & Castles A Magical Journey to Scotland with WBJC! August 2-12, 2018 Tour begins August 3rd in Scotland. Jonathan Palevsky has been with WBJC since 1986 and has been the station’s Program Director since 1990. He is originally from Montreal and came to Baltimore in 1982 to study classical guitar at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University. Edinburgh seen from Calton Hill On WBJC he is the host of the WBJC Opera Preview, the music review program Face the Music, Music in Maryland, and is Join the indefatigable Jonathan Palevsky co-host of Word on Wine. His current off-air obsessions include for another magical musical journey, this skiing, playing guitar and being the host of Cinema Sundays. Simon Rattle time to bonnie Scotland. The highlight is attendance at the 71st annual Edinburgh International Festival, arguably the world’s best arts festival, in one of Europe’s most beautiful capitals. A mark of this great event, you will enjoy a wide variety of performances including two H H H H by the London Symphony led by its new music director Sir Simon Rattle, Tour Highlights back home after his long tenure with the Berlin Philharmonic; a production • Prime tickets to five of Rossini’s sparkling The Barber of Seville from Paris; recitals by the performances at the superb pianists Piotr Anderszewski and Marc-André Hamelin, the latter Edinburgh Festival, including an opera, two with the Takacs Quartet; and the spectacular Royal Military Tattoo, beneath orchestral concerts, and two recitals Edinburgh Castle. You will also have the option of attending a concert • Prime tickets to the Royal Military Tattoo at Edinburgh Castle performance of Wagner’s Siegfried with a first-rate cast, or the National • Optional concert of Wagner’s Siegfried, or a play by Theatre of Scotland’s amazing chamber musical, Midsummer, the National Theatre of Scotland set in Edinburgh. -

Heart and Soul Explore

ARGYLL How many cities have such incredible wild landscape within Glasgow and Argyll for an unforgettable break. You can expect striking distance? Enjoy the bright lights of Glasgow and then a warm welcome and a big dose of west coast humour where head for the hills and coast of Argyll. You can be there in less ever you go. The people – from the Glasgow taxi drivers to TRAVEL than an hour. Whether you like to play hard, immerse yourself the Argyll artisan producer – will make your experience in the Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city, and Argyll and the Isles, Scotland’s in history and culture or seek out gastronomic wonders, pair Heart & Soul of Scotland even more memorable. Adventure Coast are located on each other’s doorstep. Visiting couldn’t be easier as both destinations are served by international and regional airports, well connected by trains from across the UK, and accessible by bus, car and bike on Scotland’s extensive road, rail ARGYLL From the theatres to the legendary music venues, Glasgow’s and ferry network. cultural scene is buzzing. It’s a fantastic foodie destination too, #5 CLYDE SEA LOCHS with cafes, restaurants and breweries galore. Argyll is the place The Clyde Sea Lochs are easily Glasgow is served by Glasgow International Airport and there are twice daily to go for food and drink made – and served - with passion. The accessed by train from the city. Find Loganair flights to Tiree, Islay and Campbeltown. There are frequent bus links CULTURE LOVING out about the ‘Helensburgh Heroes’ from the airport into the city and regular West Coast Motors bus services region’s seafood and game is appreciated by food lovers around and discover some fabulous places to departing from Buchanan Street Bus Station to the towns of Argyll and the globe, and there’s an array of restaurants, cafés and hotels FOODIES eat and drink. -

Nether Largie Mid Cairn Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC096 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13298) Taken into State care: 1932 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE NETHER LARGIE MID CAIRN We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE NETHER LARGIE MID CAIRN CONTENTS 1 Summary -

English 12: British Literature and Composition Pastoral Poetry Notes

English 12: British Literature and Composition Pastoral Poetry Notes Standards: ELABLRL1 – The student demonstrates comprehension by identifying evidence (i.e., examples of diction, imagery, point of view, figurative language, symbolism, plot events, main ideas, and characteristics) in poetry and uses this evidence as the basis for interpretation. ELABLRL3 - The student deepens understanding of literary works by relating them to their contemporary context or historical background, as well as to works from other time periods. Bloom’s Taxonomy Levels: Knowing and Understanding Pastoral poetry depicts country life in idyllic, idealized terms. The term pastoral derives from the Latin word that means shepherd, and originally, pastorals were about rural life, shepherds, and nymphs (minor divinities of nature in classical mythology represented as beautiful maidens dwelling in the mountains, forests, trees, and waters). Pastoral poetry contains the following elements: Idealized setting In pastoral poems, the environment of rural life is idealized--time is always spring or summer; shepherds are young and enjoy a life of song and love; and the sheep seem to take care of themselves. Mood Renaissance poets did not use the pastoral form to accurately and realistically portray rustic life but to convey their own emotions and ideas about life and love. The mood of the poem is the overall feeling that the poem evokes, or causes in the reader. Tone Tone is the attitude the speaker takes toward his or her subject. Dialogue Though these two poems are by different authors, they function as a pair with the two speakers talking directly to one another. Responding to Marlowe’s poem, Raleigh pretends to take each of the shepherd’s idealized promises about pastoral life literally and then allows the nymph to prove each promise to be empty or incapable of fulfillment due to the harsh reality of rural life.