Derrick Carnall Interviewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association MAY 2008

ThePioneerThe Newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association MAY 2008 www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk A PROUD RETURN Good turnout as Bicester Town welcomes home the regiment ThePioneer e are currently preparing for this year's he following is a message from Brigadier CB Reunion Weekend which, once again, will Telfer CBE, Chairman of the RPC Association... W coincide with 23 Pnr Regt's Open Day. A T It is time for me to stand down as your booking form for the weekend is attached, Chairman and to pass the baton to my successor. accommodation will be granted on a first come By the time you read this that will have been done. first served basis. During these last few years we have Also attached are the usual draw tickets for the undertaken significant changes to the way in Derby Draw, please give this your support as it which we do business as an Association. The helps to fund Association functions. However, if merging of our resources with the other you find that you are unable to sell these tickets Associations within the RLC has been completed and do not wish to purchase them yourself with the result that systems and staffing support please let me know and future tickets will not be are now in place which will ensure that our sent to you. affairs will be efficiently managed for the future. Front Cover The last ‘extended’ Newsletter was very well The way in which benevolent needs are met CO 23 Pioneer Regiment RLC received especially the complete book ”It don't and the way in which members can keep in leads the Regiment through cost you a Penny”, the complementary messages touch through Association events is as well Bicester town centre were appreciated. -

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty Officer 309198 H.M.S “Valkyrie” Royal Navy. Killed by an explosion 22nd December 1917. James Adams was the 34 year old husband of Eliza Emma Duckham (formerly Adams of 4, Halesleigh Road, Bridgwater. Born at Huntworth. Bridgwater (Wembdon Road) Cemetery Church portion Location IV. 8. 3. Adams Albert James Corporal 266852 1st/6th Battalion TF Devonshire Regiment. Died 9th February 1919. Husband of Annie Adams, of Langley Marsh, Wiveliscombe, Somereset. Bridgwater (St Johns) Cemetery. Ref 2 2572. Allen Sidney Private 7312 19th (County of London) Battalion (St Pancras) The London Regiment (141st Infantry Brigade 47th (2nd London) Territorial Division). (formerly 3049 Somerset Light Infantry). Killed in action 14th November 1916. Sydney Allen was the 29 year old son of William Charles and Emily Allen, of Pathfinder Terrace, Bridgwater. Chester Farm Cemetery, Zillebeke, West Flanders, Belgium. Plot 1. Row J Grave 9. Andrews Willaim Private 1014 West Somerset Yeomanry. Died in Malta 19th November 1915. He was the son of Walter and Mary Ann Andrews, of Stringston, Holford, Bridgwater. Pieta Military Cemetery, Malta. Plot D. Row VII. Grave 3. Anglin Denis Patrick Private 3/6773 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. (11th Infantry Brigade 4th Division). Killed in action during the attack on and around the “Quadrilateral” a heavily fortified system of enemy trenches on Redan Ridge near the village of Serre 1st July 1916 the first day of the 1916 Battle of the Somme. He has no known grave, being commemorated n the Thiepval Memorial to the ‘Missing’ of the Somme. Anglin Joseph A/Sergeant 9566 Mentioned in Despatches 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. -

Botswana and the Two World

Botswana and the two World Wars: page 2 - Botswana forces in WW2 http://www.thuto.org/ubh/bw/ww/wwp2.htm View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main University of Botswana History Department || Home Page || Site Index World Wars home page || World Wars page 1: Bibliography World War I & II Pages BOTSWANA (BECHUANALAND PROTECTORATE) AND THE TWO WORLD WARS Page 2 CHECKLIST OF BECHUANALAND COMPANIES OF THE AFRICAN PIONEER CORPS (ALLIED 5th, 8th, & 9th ARMIES) AND SUMMARY OF THEIR ACTIVITIES 1941-19466 summarized from R.A.R. (Alan) Bent, Ten Thousand Men of Africa: The Story of the Bechuanaland Pioneers and Gunners 1941-1946 London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office for the Bechuanaland Government, 1952. 128pp. [Alan Bent was seconded from Bechuanaland Protectorate district administration to serve as a lieutenant rising to major with APC Bechuana companies No. 1972 (in Syria & Lebanon), No. 1977 (probably with them in Egypt, Sicily & Monte Cassino), No. 1966 (with them in Italy as far as Trieste), and No. 1989 (in Palestine & Rhodes/ Greek Islands)] Only a minority of Bechuana servicemen saw action in Italy from Sicily up through the battle of Monte Cassino to the Austrian and Jugoslav borders. Bent explains (p.89) that most servicemen stayed in and moved around the Middle-East sector (Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, & Syria) during the war because the Middle East was both the main military supply base for North Africa/ Italy and a rear base for the Far East: it “was the pivot of British arms and of war munitions and supplies abroad, and the Bechuana and Basuto were pre-eminent as a loyal, dependable and efficient labour force to be rushed wherever heavy labour was needed.” Glossary Pioneers (in African Pioneer Corps, originally African Auxiliary Pioneer Corps, a regiment of the Royal Pioneer Corps of British Army): soldier workers in construction, dock & transport loading, equipped with rifles for camp guard duty & personal defence when working near front-line. -

2006 April Newsletter

AssociationRoyal Pioneer Corps Shop Welcome to the RPC Association Shop... New Corps Tie > A new tie is now available Please send from HQ RPC Association, cheques although keeping the same payable to pattern the new one RPC Association contains the Corps Badge ^ Cufflinks ^ Cufflinks ^ Tie Pins on the blade of the tie. with your order. solid silver £20 bronze £13.50 lovely £3.50 The photograph shows Sgt D Pettit with the first new tie! £7.50 < Blazer Badge ^Bow Tie silk & wire £7 adjustable £5.50 ^ Wall Shields hand painted £20 ^Bow Tie silk £14 ^Tie ^ Wall Shields polyester £6 85-93 badge £20 < “A War History of the Royal Pioneer Corps 1939-45” by Major E H Rhodes Wood This book, long out of print, is now available on CD-Rom at a cost of £11 ^ Bronze Statue ^ Blazer Buttons why not order & gilt on brass, engraved, collect at Reunion 6 small and 6 large £22 Weekend to save ^ Photograph CD’s postage The Association has a large £60 + £5 postage number of old photographs < “Royal Pioneers 1945-1993” taken over the years. by Major Bill Elliott They are now available on CDs (each CD contains The Post-War History of the Corps was approx 400 photographs). £2 each written by our honorary treasurer, Major Bill Elliott, who generously donated his They are: work and rights entirely for the - Named, partially named vol. 1 Association's benefit. It was published by - Named, partially named vol. 2 - Unknown Images, Malvern in May 1993 and is on ^ Seasons Greetings Cards - Reunion Weekends sale in the book shops at £24. -

2004 February Newsletter

THE ROYAL PIONEER CORPS ASSOCIATION 51 St. Georges Drive - London - SW1V 4DE T: 020 7834 0415 F: 020 7828 5860 E: [email protected] PIONEER REUNION WEEKEND - 2004 The Pioneer Reunion Weekend is once again, thanks to the Commanding Officer 23 Pioneer Regiment RLC, to be held at Bicester on 9/10 July 2004. A Booking Form is at page 18 of this Newsletter, this must be returned to HQ RPC Association by no later than 28 June 2004. Once again accommodation is going to prove difficult with the Regiment undergoing Operation SLAM, the refurbishment of St David's Barracks. Accommodation has been offered at St George's Barracks (some six miles away) and transport will be provided on a regular basis. This accommodation will be in large barrack rooms with bunk beds, if this is unsuitable for anyone a list of local Hotels/Guest Houses can be supplied on LONDON LUNCH application to HQ RPC Association. Transport to/from these Victory Services Club, Seymour St, London hotels/guest houses will be provided whenever possible. The London Lunch will be held in the Trafalgar Rooms, Services Victory Club, Seymour St, London on Saturday 12 A programme of events is as follows: June 2004 at 1100 hrs finishing at 3.30 p.m. (lunch will be at 1200 hrs). The dress is lounge suit or jacket and tie. The lunch 9 July 2004 is for Association members with guests, wives and children EVENT TIME LOCATION DRESS too, if the latter are big enough. The Victory Club is only three minutes from Marble Arch tube station and a two minute walk Bring a Boss 1600 hrs Cpls' Club Jacket/Tie from Marble Arch itself. -

The Field of Remembrance Westminster Abbey, Wednesday 4Th November 2020 Foreword

the field of remembrance Westminster Abbey, Wednesday 4th November 2020 Foreword Welcome to the Field of Remembrance The Poppy Factory today provides 2020 held at Westminster Abbey. employment support to hundreds of ex-forces men and women with health In this exceptional year we find ourselves conditions across the country and in their marking Remembrance in the middle of communites. a pandemic. The opening of the Field of Remembrance is an event we look The Field will be completed on forward to every year. An opportunity to Wednesday, 4th November and there will connect with the military family and pay be an online gallery of individual plots at our respects to those who have lost their www.poppyfactory.org lives in conflict. Due to virus restrictions there will be dramatically fewer attendees to the opening than in previous years, but that will not stop us from marking this very important occasion. This year a total of 308 plots have been laid out in the names of military associations and other organisations. Remembrance crosses and symbols are provided so that ex-Service men and women, as well as members of the public, can plant a symbol in memory of fallen comrades and loved ones. The Poppy Factory began in 1922, offering wounded, injured and sick veterans a place of employment producing Remembrance products for The Poppy Factory staff and volunteers help build the The Royal British Legion Field of Remembrance every year. and the Royal Family. order of service 1:55PM Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall arrives at the Field of Remembrance and is greeted by The Dean of Westminster Abbey (The Very Reverend David Hoyle). -

Three Meanings of Millennium

AJR ormation Volume LV No. 1 January 2000 ±3 (to non-members) Don't miss... Some refleaions on the word on everybody's lips Land of promise Ronald Channing p5 Glimpses of Austria jussy Brainin pl3 Three meanings of millennium Both pen and iven that the word millennium is currently resemble the First more than the Second. (To read sword bandied about randomly it may not be amiss ers who jib at taking such a long-term view we say to try and tease out the different meanings he death, G that the history of the Jews is arguably longer than that attach to the term. within the anybody else's). same week, The first is obviously the spiritual Judeo-Christian And as we look at the Jewish situation a thousand T connotation. In this reading, millennium signifies years ago we find that all the worst horrors - the of Joseph Heller and Alexander the thousand year period of Messianic rule which is Crusades, the expulsions, the yellow badge, the Baron was a to precede the Last Judgement and the world to blood libel, the Inquisition, etc. were yet to come. truly symbolic come. One would have to be an inspissated pessimist to coincidence. Both The second is 'chronological': a metric subdivision fear that, with neady half the world's Jews currently men were of of time, as the next order of magnitude following in their own state and the rest largely resident in the humble immigrant on from year, decade and century. enlightened West, the upcoming millennium will in origin and served The third is (narrowly) historical. -

Extraordinary Heroes in Alphabetical Order of Their Surnames

Alphabetical list The following list gives the names of everyone featured in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery: Extraordinary Heroes in alphabetical order of their surnames. Alongside each name is given: – The area where that person can be found – The year in which their VC or GC was earned – The country where the VC or GC action took place – The basic military unit in which the person was serving at the time Name of recipient Area Year Country Regiment A Abdul Hafiz VC Aggression 1944 India 9th Jat Infantry Ackroyd, Harold, VC Sacrifice 1917 Belgium Royal Army Medical Corps Agansing Rai, VC Aggression 1944 India 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles Agar, Augustus, VC Leadership 1919 Russia HM Coastal Motor Boat 4 Alderson, Thomas, GC Skill 1940 United Kingdom ARP Rescue Parties Alexander, Ernest, VC Skill 1914 Belgium Royal Field Artillery Algie, Wallace, VC Aggression 1918 France 20th Canadian Battalion Ali Haidar, VC Initiative 1945 Italy 13th Frontier Force Rifles Anderson, William, VC Leadership 1918 France Highland Light Infantry Andrews, Henry, VC Sacrifice 1919 India Indian Medical Service Annand, Richard, VC Skill 1940 Belgium Durham Light Infantry Armitage, Selby, GC Skill 1940 United Kingdom Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Ashburnham, Doreen, GC Endurance 1916 Canada Civilian B Babington, John, GC Boldness 1940 United Kingdom Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Badlu Singh, VC Initiative 1918 Palestine 29th Lancers (Deccan Horse) Baldwin, Geoffrey, GC Skill 1942 United Kingdom Civilian Bamford, Jack, GC Sacrifice 1952 United Kingdom Civilian Barefoot, Herbert, -

Men of Burgess Hill 1939-1946

www.roll-of-honour.com The Men of Burgess Hill 1939 to 1946 Remembering the Ninety who gave their lives for peace and freedom during the Second World War By Guy Voice Copyright © 1999-2004 It is only permissible for the information within The Men Burgess Hill 1939-46 to be used in private “not for profit” research. Any extracts must not be reproduced in any publication or electronic media without written permission of the author. "This is a war of the unknown warriors; but let all strive without failing in faith or in duty, and the dark curse of Hitler will be lifted from our age." Winston Churchill, broadcasting to the nation on the BBC on 14th July 1940. Guy Voice 1999-2004 1 During the Second World War the Men of Burgess Hill served their country at home and in every operational theatre. At the outset of the war in 1939, young men across the land volunteered to join those already serving in the forces. Those who were reservists or territorials, along with many, who had seen action in the First World War, joined their units or training establishments. The citizens of Burgess Hill were no different to others in Great Britain and the Commonwealth as they joined the Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force in large numbers. Many more of the townspeople did valuable work on the land or in industry and, living close to the sea some served in the Merchant Navy. As the war continued many others, women included, volunteered or were called up to “do their bit”. -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the 2$Th of MAY, 1948 by Registered As a Newspaper

fliimb. 38301 SECOND SUPPLEMENT ( - ' TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the 2$th of MAY, 1948 by Registered as a newspaper -FRIDAY, 28 MAY, 1948 War Office, z&th May, 1948. The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany's). The KING has been graciously' pleased to confer Lt.-Col. (Hon. Brig.) H. W. HOULDSWORTH, " The Efficiency Decoration " upon the following D.S.O.. M.C. (Res. of Offrs.) (Hon. Col. Seaforth officers of the Territorial Army: — Highlanders) (Gentleman-at-Arms) (1193). ROYAL ARTILLERY. Capt. R. R. P. BURN, M.C. (62003). Col. (Hon. Maj.-Gen.) E. A. E. TREMLETT, C.B. Lt. A. CARGILL (38467). (Hon. Col. R.A.) (13234). ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. ,Lt.-Col. .(T/Col.) G. A. WADHAM (42991) Col. H. J. A. LONGMORE (87003). (T.A.R.O.). Col. W. McK. H. MCCULLAGH, D.S.O., M.C. Lt.-Col. R. A. A. EVANS (62083). (4834)- Lt.-Col. R. G. RAYMOND, M.B.E. (57884). Maj. (T/Lt.-Col.) J. B. BISHOP (68480). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) R. J. H. ABRAHAMS (91768). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) D. J. CAMPBELL (56788). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) J. S. DODD (62346). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) J. D. FINLAYSON, M.B.E. Maj. J. T. GRAHAM (62814). (56369). Maj. P. P. H. MERCHANT (57883). Maj. J. E. MCCARTNEY (57230). Maj. A. R. L. OLIVER (53973). ,. • Maj. J. G. M. STAMP (53188). ROYAL ARMY ORDNANCE CORPS. • Capt. (Hon. Maj.) R. L. EDGERTON (63852). Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) T. A. PERRY, O.B.E. (55956). Capt. A. B. C. -

It Don't Cost You a Penny” Northampton, Unfortunately Only Half of Them State Which Section and Date of Pass-Out

ThePioneerThe Newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association OCTOBER 2007 www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk SPECIAL PUBLICATION (PAGE 27) It don’t cost you a Penny Inside is the complete book, published in 1955 by the author who wrote the R.P.C. War History. by EDDIE HARWOOD (Maj EH Rhodes-Wood) A 13 year old in 1939 (PAGE 17) Diary from Stalag VIIIB (PAGE 18) Introduction to Demob (PAGE 19) Please send cheques payable to The Royal Pioneer RPC Association with your order... Royal Pioneer Corps Association, Corps Association c/o 23 Pnr Regiment RLC, St David's Barracks, SHOP Graven Hill, Bicester OX26 6HF ▲ Blazer Buttons ▲ Cufflinks ▲ Cufflinks ▲ Tie Pins gilt on brass, engraved, solid silver £20 bronze £13.50 lovely £3.50 6 small and 6 large £22 ▲ New Corps Tie A new tie is now available from HQ RPC Association, although keeping the same pattern the new one contains the Corps Badge on the ▲ Seasons Greetings Cards blade of the tie. x10 £2.50 £7.50 ▲ Wall Shields ▲ Wall Shields hand painted £20 85-93 badge £20 ▲ “A War History of the Royal Pioneer Corps 1939-45” by Major E H Rhodes Wood ▲ Blazer Badge This book, long out of print, is now available on CD-Rom at a silk & wire £7 cost of £11 ▲ “Royal Pioneers 1945-1993” by Major Bill Elliott The Post-War History of the Corps was written by Major Bill Elliott, who generously donated his work and rights entirely for the Association’s benefit. It was published by Images, Malvern in May 1993 and is on sale in the book shops at £24. -

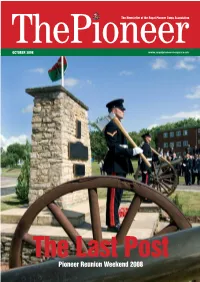

The Pioneer, Wood and Plaster Structure for Use As a Mrs Margaret Kennedy on Behalf of Issue 11, Dated 2 June 1947

ThePioneerThe Newsletter of the Royal Pioneer Corps Association OCTOBER 2008 www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk The Last Post Pioneer Reunion Weekend 2008 ■ John and Terry at the Reunion Weekend 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Steve, Tiny and Wives at the Reunion Weekend 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Jimmy Winters with wife & friends at the Reunion 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Ex QM Graham McLane at the Reunion Weekend 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Taff Durnford and his wife at the Reunion Weekend 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Checking the temperature of the beer at the Reunion 2008 Picture: Norman Brown ■ Norman Brown presents CO with painting Picture: Paul Brown ■ Col Barnes presents CO with Col McAdam’s medals Picture: Paul Brown 2 | THE ROYAL PIONEER CORPS ASSOCIATION ThePioneer t was nice to see so many attend this year's to paper. Articles are always more interesting Reunion Weekend in July, both regulars and when submitted with photographs. I those attending for the first time. All the feed I try to please most members during the one back that I have received has been positive as and half days per week that I am paid, highlighted on the letters page. A record 173 beds unfortunately it appears that I cannot satisfy all - had to be booked and with those just attending for see article on page 54. It is gratifying, however, the day I estimate that between 350 - 400 to report that both my son and I received many members attended. This must be a record since messages of support so we must be doing our 'home' moved from Northampton.