New Technology and the First Amendment: Breaking the Cycle of Repression Robert Corn-Revere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

An Anthropological Exploration of the Effects of Family Cash Transfers On

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF FAMILY CASH TRANSFERS ON THE DIETS OF MOTHERS AND CHILDREN IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Ana Carolina Barbosa de Lima Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University July, 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Eduardo S. Brondízio, PhD ________________________________ Catherine Tucker, PhD ________________________________ Darna L. Dufour, PhD ________________________________ Richard R. Wilk, PhD ________________________________ Stacey Giroux Wells, PhD Date of Defense: April 14th, 2017. ii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my research committee. I have immense gratitude and admiration for my main adviser, Eduardo Brondízio, who has been present and supportive throughout the development of this dissertation as a mentor, critic, reviewer, and friend. Richard Wilk has been a source of inspiration and encouragement since the first stages of this work, someone who never doubted my academic capacity and improvement. Darna Dufour generously received me in her lab upon my arrival from fieldwork, giving precious advice on writing, and much needed expert guidance during a long year of dietary and anthropometric data entry and analysis. Catherine Tucker was on board and excited with my research from the very beginning, and carefully reviewed the original manuscript. Stacey Giroux shared her experience in our many meetings in the IU Center for Survey Research, and provided rigorous feedback. I feel privileged to have worked with this set of brilliant and committed academics. -

Resource Magazine October 2008 Engineering and Technology for A

Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development PUBLISHED BY ASABE – AMERICAN SOCIETY OF AGRICULTURAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERS Targeted access to 9,000 international agricultural & biological engineers Ray Goodwin (800) 369-6220, ext. 3459 BIOH0308Filler.indd 1 7/24/08 9:15:05 PM FEATURES COVER STORY 5 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development Carroll Goering Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Plowing down memory lane: a top-six list of tractor changes over the last century with emphasis on those that transformed agriculture. Vol. 15, No. 7, ISSN 1076-3333 7 Adding Value to Poultry Litter Using ASABE President Jim Dooley, Forest Concepts, LLC Transportable Pyrolysis ASABE Executive Director M. Melissa Moore Foster A. Agblevor ASABE Staff “This technology will not only solve waste disposal and water pollution Publisher Donna Hull problems, it will also convert a potential waste to high-value products such as Managing Editor Sue Mitrovich energy and fertilizer.” Consultants Listings Sandy Rutter Professional Opportunities Listings Melissa Miller ENERGY ISSUES, FOURTH IN THE SERIES ASABE Editorial Board Chair Suranjan Panigrahi, North Dakota State University 9 Renewable Energy Gains Global Momentum Secretary/Vice Chair Rafael Garcia, USDA-ARS James R. Fischer, Gale A. Buchanan, Ray Orbach, Reno L. Harnish III, Past Chair Edward Martin, University of Arizona and Puru Jena Board Members Wayne Coates, University of Arizona; WIREC 2008 brought together world leaders in the fi eld of renewable energy Jeremiah Davis, Mississippi State University; from 125 countries to address the market adoption and scale-up of renewable Donald Edwards, retired; Mark Riley, University of Arizona; Brian Steward, Iowa State University; energy technologies. -

Digital Collections at the University of the Arts

The UniversiT y of The ArTs Non Profit Org 320 South Broad Street US Postage Philadelphia, PA 19102 PAID www.UArts.edu Philadelphia, PA Permit No. 1103 THE MAGAZINE OF The UniversiT y of The ArTs edg e THE edge MAGAZINE OF T he U niver si T y of T he A r T s WINTER WINTER 2013 2013 NO . 9 Edge9_Cover_FINAL.crw4.indd 1 1/22/13 12:50 PM THE from PRESIDENT A decade has passed since the publication In this issue of Edge, we examine the book’s of Richard Florida’s international bestseller theses and arguments a decade on, and The Rise of the Creative Class. This 10-year speak with a range of experts both on and of anniversary provides an opportunity to ex- the creative class, including Richard Florida amine the impact of that seminal work and himself. I think you will find their insights the accuracy of its predictions, some of them and perspectives quite interesting. bold. The book’s subtitle—“...And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, Following on the theme of the power of and Everyday Life”—speaks to the profes- creatives, we also look at the creative econ- sor and urban-studies specialist’s vision of omy of the Philadelphia region and the far- the impact this creative sector can exert on reaching impact that University of the Arts virtually all aspects of our lives. alumni and faculty have on it. You will also find features on UArts students, alumni and Since its 2002 release, many of the ap- faculty who are forging innovative entrepre- proaches to urban regeneration proposed neurial paths of their own. -

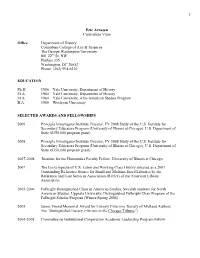

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Sundayiournal

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,459 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET JULY 11-17, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 34 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT DETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ JIM WEST/Special to the Journal Nicholle Murphy’s support for her grandmother, Teamster Meka Murphy, has been unflagging. Marching fourward Come Tuesday, it will be four yearsstrong and determined. In this editionOwens’ editorial points out the facthave shown up. We hope that we will since the day in July of 1995 that ofour the Sunday Journal, co-editor Susanthat the workers are in this strugglehave contracts before we have to put Detroit newspaper unions were forcedWatson muses on the times of happiuntil the end and we are not goingtogether any another anniversary edition. to go on strike. Although the companess and joy, in her Strike Diarywhere. on On Pages 19-22 we show offBut four years or 40, with your help, nies tried mightily, they never Pagedid 3. Starting on Page 4, we putmembers the in our annual Family Albumsolidarity and support, we will be here, break us. Four years after pickingevents up of the struggle on the record.and also give you a glimpse of somestanding of strong. our first picket signs, we remainOn Page 10, locked-out worker Keiththe far-flung places where lawn signs— Sunday Journal staff PAGE 10 JULY 11 1999 Co-editors:Susan Watson, Jim McFarlin --------------------- Managing Editor: Emily Everett General Manager: Tom Schram Published by Detroit Sunday Journal Inc. -

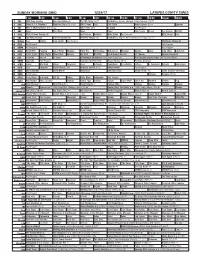

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Department of Energy

Vol. 76 Tuesday, No. 95 May 17, 2011 Part II Department of Energy Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Okanogan Public Utility District No. 1 of Okanogan County, WA; Notice of Availability of Draft Environmental Assessment; Notice VerDate Mar<15>2010 17:06 May 16, 2011 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\17MYN2.SGM 17MYN2 sroberts on DSK69SOYB1PROD with NOTICES 28506 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 95 / Tuesday, May 17, 2011 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY concludes that licensing the project, up to 6,000 characters, without prior with appropriate environmental registration, using the eComment system Federal Energy Regulatory protective measures, would not at http://www.ferc.gov/docs-filing/ Commission constitute a major federal action that ecomment.asp. You must include your [Project No. 12569–001] would significantly affect the quality of name and contact information at the end the human environment. of your comments. For assistance, Okanogan Public Utility District No. 1 A copy of the draft EA is available for please contact FERC Online Support. of Okanogan County, WA; Notice of review at the Commission in the Public Although the Commission strongly Availability of Draft Environmental Reference Room or may be viewed on encourages electronic filing, documents Assessment the Commission’s Web site at http:// may also be paper-filed. To paper-file, www.ferc.gov using the ‘‘eLibrary’’ link. mail an original and seven copies to: In accordance with the National Enter the docket number excluding the Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary, Federal Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and last three digits in the docket number Energy Regulatory Commission, 888 the Federal Energy Regulatory field to access the document. -

Camp Meeting 1992

GC President Folkenberg June I, 1992 —page 6-8 Adventist Book Center Camp Meeting Special Your conference newsletter—pages 17-20 A Healing Ministry—pages 21-24 VISITOR STAFF Editor: Richard Duerksen Managing Editor: Charlotte Pedersen Coe Assistant Editor: Randy Hall DON'T Communication Intern: Elaine Hamilton LEAVE Design Service: t was camp meeting time. Reger Smith Jr. CAMP All the packing was done. Already there was longing Circulation Manager: for beautiful sights that would be seen as familiar Dianne Liversidge WITHOUT Pasteup Artist: HIM roadways were traversed again. There would be Diane Baier catching up to do with acquaintances usually seen The VISITOR is the Seventh-day Ad- ventist publication for people in the Colum- only at camp time. Camp meeting was a tradition bia Union. The different backgrounds and for this family. It was a tradition for the entire com- spiritual gifts of these people mean that the VISITOR should inspire confidence in the munity where they lived. Saviour and His church and should serve as a networking tool for sharing methods that There were three special times of coming together members, churches and institutions can use in ministry. Address all editorial correspon- for spiritual refreshment and fellowship. The Pass- dence to: Columbia Union VISITOR, 5427 Twin Knolls Road, Columbia, MD 21045. over was one of the three, and it was the most popu- One-year subscription price—$7.50. lar. There would be a recounting of the blessings of COLUMBIA UNION CONFERENCE God to His people and reading of the law. There Washington (301) 596-0800 would be discussion and exhortations by those who Baltimore (410) 997-3414 President R.M. -

The Passionate Mind of Maxine Greene: 'I Am…Not Yet'

The Passionate Mind of Maxine Greene Dedication: For Maxine Greene Note: All royalties from this collection go to Center for the Arts, Social Imagination, and Education founded by Maxine Greene at Teachers College, Columbia University. The Passionate Mind of Maxine Greene: ‘I Am…Not Yet’ Edited by William F.Pinar UK Falmer Press, 1 Gunpowder Square, London, EC4A 3DE USA Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 © William F.Pinar 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 1998 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98072-7 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0 7507 0812 3 cased ISBN 0 7507 0878 6 paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available on request Cover design by Caroline Archer Cover printed in Great Britain by Flexiprint Ltd., Lancing, East Sussex. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders for their permission to reprint material in this book. The publishers would be grateful to hear from any copyright holder who is not here acknowledged and will undertake to rectify any errors or omissions in future editions of this book. -

Snapper Grouper Regulatory Amendment 30

Regulatory Amendment 30 to the Fishery Management Plan for the Snapper Grouper Fishery of the South Atlantic Region Rebuilding schedule, seasonal prohibition, and commercial trip limit for red grouper Environmental Assessment Regulatory Impact Review Initial Regulatory Flexibility Analysis September 9, 2019 A publication of the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number FNA15NMF4410010 Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in the document ABC acceptable biological catch ESA Endandered Species Act ACL annual catch limits EO Executive Order ACT annual catch target F a measure of the instantaneous rate of AM accountability measures fishing mortality AP Advisory Panel F30%SPR fishing mortality that will produce a static SPR = 30% APA administrative procedure act FCURR the current instantaneous rate of APAIS Access-Point Angler Intercept Survey fishing mortality B a measure of stock biomass in either FEP fishery ecosystem plan weight or other appropriate unit FES Fishing Effort Survey BCURR the current stock biomass FMP fishery management plan BMSY the stock biomass expected to exist under equilibrium conditions when FMSY the rate of fishing mortality expected fishing at FMSY to achieve MSY under equilibrium conditions and a corresponding BOY the stock biomass expected to exist biomass of BMSY under equilibrium conditions when fishing at FOY FMU fishery management unit BPA Byatch Practability Analysis FOY the rate of fishing mortality expected to achieve OY under equilibrium