The Riddim Method: Aesthetics, Practice, and Ownership in Jamaican Dancehall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

The Lions - Jungle Struttin’ for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 2/19/2008

THE LIONS - JUNGLE STRUTTIN’ FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 2/19/2008 The LIONS is a unique Jamaican-inspired ------------------------------------------------------------- outfit, the result of an impromptu recording 2 x LP Price 1 x CD Price session by members of Breakestra, Connie ------------------------------------------------------------- Price and the Keystones, Rhythm Roots 01 Thin Man Skank All-Stars, Orgone, Sound Directions, Plant 02 Ethio-Steppers Life, Poetics and Macy Gray (to name a few). Gathering at Orgone's Killion Studios, in Los Angeles during the Fall of 2006, they created 03 Jungle Struttin' grooves that went beyond the Reggae spectrum by combining new and traditional rhythms, and dub mixing mastery with the global sounds of Ethiopia, Colombia and 04 Sweet Soul Music Africa. The Lions also added a healthy dose of American-style soul, jazz, and funk to create an album that’s both a nod to the funky exploits of reggae acts like Byron 05 Hot No Ho Lee and the Dragonaires and Boris Gardner, and a mash of contemporary sound stylings. 06 Cumbia Del Leon The Lions are an example of the ever-growing musical family found in Los Angeles. There is a heavyweight positive-vibe to be found in the expansive, sometimes 07 Lankershim Dub artificial, Hollywood-flavored land of Los Angeles. Many of the members of the Lions met through the LA staple rare groove outfit Breakestra and have played in 08 Tuesday Roots many projects together over the past decade. 09 Fluglin' at Dave's Reggae is a tough genre for a new ensemble act, like the Lions, to dive head-first into and pull off with unquestionable authenticity. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

71 Reggae Festival Guide 2006

71 71 ❤ ❤ Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 RED, GOLD & GREEN MMEMORIESE M O R I E S Compiled by Wendy Russell Alton Ellis next started a group together: ALTON ELLIS AND THE There are reggae artists I treasure, with songs I FLAMES. The others had their careers too and I later started my play every radio show, no matter that the CD is no own group called WINSTON JARRETT AND THE RIGHTEOUS longer current. One such artist is roots man, WINSTON FLAMES. JARRETT and the RIGHTEOUS FLAMES, so I searched him out to fi nd what might be his own fond memory: We just had our history lesson! Can you imagine I grew up in Mortimer Planno, one of Rastafari’s most prominent Kingston, Jamaica elders, living just down the street? What about this in the government next memory - another likkle lesson from agent and houses there. manager, COPELAND FORBES: The streets are My memory of numbered First SUGAR MINOTT is Street and so on, from 1993 when I to Thirteenth Street. did a tour, REGGAE I lived on Fourth, SUPERFEST ‘93, ALTON ELLIS lived which had Sugar on 5th Street. He Minott, JUNIOR REID was much older and MUTABARUKA than me, maybe along with the 22. We were all DEAN FRASER-led good neighbors, 809 BAND. We did like a family so to six shows in East speak. MORTIMER Germany which PLANNO lived was the fi rst time Kaati on Fifth too and since the Berlin Wall Alton Ellis all the Rasta they came down, that an come from north, authentic reggae Sugar Minott south, east and west for the nyabinghi there. -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer. -

Barrington Levy Living Dangerously Mp3, Flac, Wma

Barrington Levy Living Dangerously mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Living Dangerously Country: Jamaica Released: 1995 Style: Reggae, Dub, Ragga MP3 version RAR size: 1500 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1808 mb WMA version RAR size: 1510 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 884 Other Formats: MPC MIDI VOX MP2 WMA XM MP1 Tracklist A –Barrington Levy / Bounty Killa* Living Dangerously B –Jah Screw Living Dangerously (Version) Credits Producer – Jah Screw Notes Distributed by Sonic Sounds. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounti Killer* - Living none Jamaica 1995 / Bounti Killer* International Dangerously (7") Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy RAS 7062 Bounty Killer - Living RAS Records RAS 7062 US 1995 / Bounty Killer Dangerously (12") Barrington Levy & Barrington Levy Bounty Killer - Living Time 1 none none Jamaica 1995 & Bounty Killer Dangerously (7", MP, International RP) Barrington Levy & Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounty Killer - Living none Jamaica Unknown & Bounty Killer International Dangerously (7", RP) Barrington Levy / Barrington Levy Time 1 none Bounty Killer - Living none Jamaica 1996 / Bounty Killer International Dangerously (7") Related Music albums to Living Dangerously by Barrington Levy Barrington Levy - Bad Talk Barrington Levy - Under The Sensi Barrington Levy & Ce'cile - My Woman Barrington Levy & Josey Wales - Pick Your Choice Barrington Levy - Don't Throw It All Away Barrington Levy - A Blessing From Above Barrington Levy & Beenie Man - Under Mi Sensi Slaughter & Barrington Levy - Ragga Muffin Time Barrington Levy & Gregory Peck - Here I Come Barrington Levy - English Man Barrington Levy - Struggler Barrington Levy - Under Mi Sensi. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

JAMAICA MUSIC COUNTDOWN Apr 20

JAMAICA MUSIC COUNTDOWN BY RICHARD ‘RICHIE B’ BURGESS APR 20 - 26, 2018 TOP 25 DANCE HALL SINGLES TW LW WOC TITLE/ARTISTE/LABEL 01 2 14 Family – Popcaan – Pure Music Productions (1wk@#1) U-1 02 3 13 Body Of A Goddess – Mitch & Dolla Coin – Emperor Productions U-1 03 1 14 Pine & Ginger – Amindi K. Fro$t, Tessellated & Valleyz – Big Beat Records (1wk@#1) D-2 04 6 12 A Mill Fi Share – Shane O – Kswizz Music U-2 05 7 11 They Don’t Know – Masicka – TMG Production U-2 06 9 7 Bawl Out – Dovey Magnum – Journey Music U-3 07 4 17 Yabba Dabba Doo – Vybz Kartel – Purple Skunk Records (1wk@#1) D-3 08 10 9 Stay So – Busy Signal – Warriors Musick Productions U-2 09 5 16 Lebeh Lebeh – Ding Dong – Romeich Entertainment (pp#3) D-4 10 12 8 Mad Love – Sean Paul & David Guetta feat. Becky G – Virgin U-2 11 13 6 Walking Trophy – Hood Celebrity – KSR Group U-2 12 14 6 Love Situation – Jada Kingdom – Popstyle Music U-2 13 15 6 Breeze – Aidonia & Govana – 4th Genna Music & JOP Records U-2 14 8 19 Graveyard – Tarrus Riley – Head Concussion Records (2wks@#1) D-6 15 11 17 Duh Better Than This – Bounty Killer – Misik Muzik (pp#7) D-4 16 18 5 Duffle Bag – Spice – Spice Official Ent. U-2 17 19 5 I’m Sanctify – Sean Paul feat. Movado – Troyton Music U-2 18 20 4 Simple Blessings – Tarrus Riley feat. Konshens – Chimney Records U-2 19 16 19 Suave - Alkaline – Chimney Records (1wk@#1) D-3 20 22 4 War Games – Shabba Ranks feat. -

View Song List

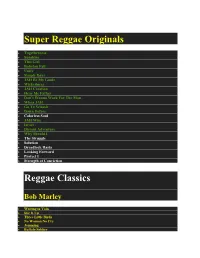

Super Reggae Originals Togetherness Sunshine This Girl Babylon Fall Unify Simple Days JAH Be My Guide Wickedness JAH Creation Hear Me Father Don’t Wanna Work For The Man Whoa JAH Go To Selassie Down Before Colorless Soul JAH Wise Israel Distant Adventure Why Should I The Struggle Solution Dreadlock Rasta Looking Forward Protect I Strength of Conviction Reggae Classics Bob Marley Waiting in Vain Stir It Up Three Little Birds No Woman No Cry Jamming Buffalo Soldier I Shot the Sherriff Mellow Mood Forever Loving JAH Lively Up Yourself Burning and Looting Hammer JAH Live Gregory Issacs Number One Tune In Night Nurse Sunday Morning Soon Forward Cool Down the Pace Dennis Brown Love and Hate Need a Little Loving Milk and Honey Run Too Tuff Revolution Midnite Ras to the Bone Jubilees of Zion Lonely Nights Rootsman Zion Pavilion Peter Tosh Legalize It Reggaemylitis Ketchie Shuby Downpressor Man Third World 96 Degrees in the Shade Roots with Quality Reggae Ambassador Riddim Haffe Rule Sugar Minott Never Give JAH Up Vanity Rough Ole Life Rub a Dub Don Carlos People Unite Credential Prophecy Civilized Burning Spear Postman Columbus Burning Reggae Culture Two Sevens Clash See Dem a Come Slice of Mt Zion Israel Vibration Same Song Rudeboy Shuffle Cool and Calm Garnet Silk Zion in a Vision It’s Growing Passing Judgment Yellowman Operation Eradication Yellow Like Cheese Alton Ellis Just A Guy Breaking Up is Hard to Do Misty in Roots Follow Fashion Poor and Needy -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr.