Theater Nuclear Forces in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Should Be Done About Tactical Nuclear Weapons?

THE ATLANTIC COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES What Should Be Done About Tactical Nuclear Weapons? GEORGE LEWIS & ANDREA GABBITAS WITH ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY BY: EDWARD ROWNY & JOHN WOODWORTH OCCASIONAL PAPER What Should Be Done About Tactical Nuclear Weapons? George Lewis & Andrea Gabbitas With Additional Commentary By: Edward Rowny & John Woodworth MARCH 1999 OCCASIONAL PAPER For further information about the Atlantic Council of the United States and/or its Program on International Security, please call (202) 778-4968. Information on Atlantic Council programs and publications is available on the world wide web at http://www.acus.org Requests or comments may be sent to the Atlantic Council via Internet at [email protected] THE ATLANTIC COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES 10TH FLOOR, 910 17TH STREET, N.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20006 CONTENTS Foreword by David C. Acheson……..…….………………………………………….…iv Executive Summary………………………………………………………………….. vi Problems of Definition……………………………………………………………. 1 History of Tactical Nuclear Weapons……………..……….………….………….... 4 The Current State of Tactical Nuclear Weapons…………………………….…….. 6 United States………..………………………………………………………... 6 Russia………………………………….…………………………………...… 7 Other Countries……………….………………………………………………8 Recent Discussions and Proposals on TNWs……….………………………….…... 8 Synthesis…………………..……………………………………………….…….. 11 Why Keep TNWs?……………………………………………………..…….. 11 Why Limit TNWs?…………………………………………………………….15 Why Now?……...……………………………………………………………17 A Specific Proposal………………………………………………………………..18 Phase 1.……………………………………………………………………21 Phase -

Library of Congress Classification

R MEDICINE (GENERAL) R Medicine (General) Periodicals. Societies. Serials 5 International periodicals and serials 10 Medical societies Including aims, scope, utility, etc. International societies 10.5.A3 General works 10.5.A5-Z Individual societies America English United States. Canada 11 Periodicals. Serials 15 Societies British West Indies. Belize. Guyana 18 Periodicals. Serials 20 Societies Spanish and Portuguese Latin America 21 Periodicals. Serials 25 Societies 27.A-Z Other, A-Z 27.F7 French Europe English 31 Periodicals. Serials 35 Societies Dutch 37 Periodicals. Serials 39 Societies French 41 Periodicals. Serials 45 Societies German 51 Periodicals. Serials 55 Societies Italian 61 Periodicals. Serials 65 Societies Spanish and Portuguese 71 Periodicals. Serials 75 Societies Scandinavian 81 Periodicals. Serials 85 Societies Slavic 91 Periodicals. Serials 95 Societies 96.A-Z Other European languages, A-Z 96.H8 Hungarian Asia 97 English 97.5.A-Z Other European languages, A-Z 97.7.A-Z Other languages, A-Z Africa 98 English 98.5.A-Z Other European languages, A-Z 98.7.A-Z Other languages, A-Z 1 R MEDICINE (GENERAL) R Periodicals. Societies. Serials -- Continued Australasia and Pacific islands 99 English 99.5.A-Z Other European languages, A-Z 99.7.A-Z Other languages, A-Z Indexes see Z6658+ (101) Yearbooks see R5+ 104 Calendars. Almanacs Cf. AY81.M4 American popular medical almanacs 106 Congresses 108 Medical laboratories, institutes, etc. Class here papers and proceedings For works about these organizations see R860+ Collected works (nonserial) Cf. R126+ Ancient Greek and Latin works 111 Several authors 114 Individual authors Communication in medicine Cf. -

EURASIA Russian Heavy Artillery

EURASIA Russian Heavy Artillery: Leaving Depots and Returning to Service OE Watch Commentary: The Soviet Union developed large caliber artillery, such as the 2S4 ‘Tyulpan’ 240mm mortar and the 2S7 ‘Pion’ 203mm howitzer, to suppress lines of communication, destroy enemy headquarters, tactical nuclear weapons, logistic areas, and other important targets and to destroy urban areas and field fortifications. After the end of the Cold War, the Russian Federation placed most of these large caliber artillery systems into long-term storage depots for several reasons. The first is that they were intended to deliver nuclear, as well as conventional, munitions (the end of the Cold War meant that a long-range tactical nuclear weapon delivery was no longer needed). Another reason is that better tube (2S19M Msta-SM) and missile (MLRS/SRBM/GLCM) systems, such as new 300mm MLRS platforms, the Iskander missile system, and the 2S19M Msta-SM 152mm howitzer, allow Russia to fulfill many of the same tasks as large caliber artillery to varying degrees. The 2S4 ‘Tyulpan’ self-propelled mortar is equipped with a 240mm 2B8 mortar mounted on a modified Object 123 tracked chassis (similar to the 2S3 Akatsiya self-propelled howitzer) with a V-59 V-12, 520 horsepower diesel engine, capable of 60 km/h road speed. The Tyulpan has a crew of four, but five additional crewman are carried in the support vehicle that typically accompanies it. The system is capable of firing conventional, chemical, and nuclear munitions at a rate of one round per minute, although Russia reportedly now only has conventional munitions in service. -

New Summer Season

New Summer Season Furniture Catalog — Live life outdoors® — Nomah® Nomah® 3 Seat Sofa W90" x D36" x H30" $4,699 (Slub Linens fabric) Nomah® Lounge Chair W40" x D36" x H30" $2,749 (Slub Linens fabric) Nomah® Coffee Table W40" x D40" x H12" $599 Choose your own cover from our outdoor fabric range. 5 Bronte The staple table for summer entertaining a b Find our furniture range online at ecooutdoorusa.com a. Bronte Dining Table W87" x D40" x H30" W107" x D40" x H30" W166" x D40" x H30" $2,499 | $2,899 | $4,999 b. Bronte Bench Seat Bronte Stool W69" x D18" x H19" W500 x D500 x H460 W87" x D18" x H19" $399 $999 | $1,199 6 ® Barwon Sophisticated, European-inspired design a. Barwon® Dining Chair W20" x D25" x H35" $499 b. Barwon® Dining Armchair W23" x D25" x H35" $549 c. Barwon® Bar Stool W20" x D25" x H45" $649 ® d. Barwon Side Table a W18" x D16" x H16" $199 Find our furniture range online at ecooutdoorusa.com b c d 9 Porto & Hux Modern & slimline design a. Porto Dining Table W71" x D36" x H30" $1,599 b. Porto Extending Dining Table W87-111" x D40" x H30" a $2,599 c. Porto Dining Table W36" x D36" x H30" $899 d. Porto Bench W63" x D18" x H19" W78" x D18" x H19" $799 | $999 e. Hux Dining Chair W19" x D21" x H34" b $319 Find our furniture range online at ecooutdoorusa.com c d e 10 The Hayfield combines unique curved arms Hayfield and refined componentry for a timeless look. -

Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592

Technical Data Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592 Topic Page Description 2 Heater Element Selection Procedure 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables 5 Heater Element Selection Tables 6 Additional Resources These documents contain additional information concerning related products from Rockwell Automation. Resource Description Industrial Automation Wiring and Grounding Guidelines, publication 1770-4.1 Provides general guidelines for installing a Rockwell Automation industrial system. Product Certifications website, http://www.ab.com Provides declarations of conformity, certificates, and other certification details. You can view or download publications at http://www.rockwellautomation.com/literature/. To order paper copies of technical documentation, contact your local Allen-Bradley distributor or Rockwell Automation sales representative. For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Heater Element Specifications Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Type J — CLASS 10 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Type WL — CLASS 30 Note: Heater Element Type W/WL does not currently meet the material Type W Heater Elements restrictions related to EU ROHS Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). -

5/1/2021 to 5/2/2021 Meet Program

Mission Viejo Nadadores HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - Page 1 2021 May 1-2 SCY MVN SPMS Intrasquad - 5/1/2021 to 5/2/2021 Meet Program Heat 2 of 2 Finals Event 1 Mixed 1650 Yard Freestyle 2 Bennett, Mike P M50 MVN-CA 2:16.00 Lane Name Age Team Seed Time 3 Flatman, Ashley A W24 MVN-CA 2:08.28 Heat 1 of 1 Finals 4 Mester, Matt J M41 MVN-CA 2:10.00 2 Moore Barnett, Barbara W60 MVN-CA 29:56.53 5 Bae, Alex W25 MVN-CA 2:16.08 3 Stuart, Margaret L W62 MVN-CA 26:32.89 4 Thomas, Darcy A W52 MVN-CA 29:00.00 Event 8 Mixed 200 Yard IM Lane Name Age Team Seed Time Event 2 Mixed 1000 Yard Freestyle Heat 1 of 1 Finals Lane Name Age Team Seed Time 1 Dolan LaMar, Diana W63 MVN-CA 3:20.00 Heat 1 of 1 Finals 2 Mitchell, Robert E M62 MVN-CA 2:48.48 1 Furukawa, Patty W49 MVN-CA 16:30.00 3 Foos, Todd M45 MVN-CA 2:25.00 2 Moore Barnett, Barbara W60 MVN-CA 14:30.00 4 Mester, Matt J M41 MVN-CA 2:40.00 3 Bae, Alex W25 MVN-CA 13:59.99 5 Thomas, Darcy A W52 MVN-CA 3:20.00 4 Dolan LaMar, Diana W63 MVN-CA 14:00.00 6 Wendzel Brooks, Sherry M W60 MVN-CA 3:39.00 5 Zikova, Alena W54 MVN-CA 16:30.00 6 Montrella, Beverly J W74 MVN-CA 18:30.00 Event 9 Mixed 500 Yard Freestyle Lane Name Age Team Seed Time Event 3 Mixed 400 Yard IM Heat 1 of 2 Finals Lane Name Age Team Seed Time 2 Thomas, Darcy A W52 MVN-CA 8:30.00 Heat 1 of 1 Finals 3 Zikova, Alena W54 MVN-CA 8:00.00 2 Mitchell, Robert E M62 MVN-CA 6:11.93 4 Furukawa, Patty W49 MVN-CA 8:00.00 3 Flatman, Ashley A W24 MVN-CA 5:32.59 5 Frankel, Jonathan M69 MVN-CA 12:50.00 4 Mester, Matt J M41 MVN-CA 6:00.00 Heat 2 of 2 Finals -

NEMA Motor Control

Bulletin Eutectic Alloy Overload Relays Heater Elements Selection For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Heater Element Selection Type J — CLASS 10 Table of Contents 0 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Overload Relay Type WL — CLASS 30 Class Designation...... this page Heater Element Selection ....................... this page 1 Type W Heater Elements Ambient Temperature Correction..................... this page Time — Current Characteristics............ 1-169 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables ............................. 1-170 3 Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application 4 overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). When the temperature difference is greater, see percent of its current rating. below. A Class 10 overload relay will trip in 10 seconds or less at a current 1. The Same Temperature at the Controller and the Motor — equal to 600 percent of its rating. Select the “Heater Type Number” with the listed “Full Load 5 Amperes” nearest the full load value shown on the motor A Class 20 overload relay will trip in 20 seconds or less at a current nameplate. -

Report- Non Strategic Nuclear Weapons

Federation of American Scientists Special Report No 3 May 2012 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons By HANS M. KRISTENSEN 1 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons By HANS M. KRISTENSEN Federation of American Scientists www.FAS.org 2 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 Acknowledgments e following people provided valuable input and edits: Katie Colten, Mary-Kate Cunningham, Robert Nurick, Stephen Pifer, Nathan Pollard, and other reviewers who wish to remain anonymous. is report was made possible by generous support from the Ploughshares Fund. Analysis of satellite imagery was done with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Image: personnel of the 31st Fighter Wing at Aviano Air Base in Italy load a B61 nuclear bomb trainer onto a F-16 fighter-bomber (Image: U.S. Air Force). 3 Federation of American Scientists www.FAS.org Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 About FAS Founded in 1945 by many of the scientists who built the first atomic bombs, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is devoted to the belief that scientists, engineers, and other technically trained people have the ethical obligation to ensure that the technological fruits of their intellect and labor are applied to the benefit of humankind. e founding mission was to prevent nuclear war. While nuclear security remains a major objective of FAS today, the organization has expanded its critical work to issues at the intersection of science and security. FAS publications are produced to increase the understanding of policymakers, the public, and the press about urgent issues in science and security policy. -

Strategy in the New Era of Tactical Nuclear Weapons

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Strategy in the New Era of Tactical Nuclear Weapons COL JOSEPH D. BECKER, USA Abstract Post–Cold War strategic discourse, primarily among Russian strate- gists, has challenged the precept that nuclear weapons are not useful tools of warfare or statecraft. To reduce the likelihood that such ideas will ever be tested in practice, the US must openly address hard-case scenarios and develop a coherent strategy sufficient to give adversaries pause. This article posits that the key to successfully deterring the use of tactical nuclear weapons lies not in winning an arms race but in the clear articulation of a purpose and intent that directs all aspects of US policy toward the preven- tion of nuclear war and leaves no exploitable openings for opportunistic challengers. Further, an ideal strategy would be crafted to reduce—not increase—the salience of nuclear weapons in geopolitics. The article con- siders three possible approaches to a strategy for tactical nuclear weapons, but the most desirable and effective will be a “strategy of non-use” based upon credible and well- prepared alternatives to a nuclear response. ***** he end of the Cold War ushered in a new era suggesting the pos- sibility that nuclear weapons could become a relic of the past. Prominent leaders, including US president Barack Obama, cam- paigned vociferously for measures to abolish the world’s nuclear stock- T1 piles. However, instead of moving toward a world of “nuclear zero,” the US and Russia have proceeded with nuclear modernization and capability development, and even China is quietly expanding its nuclear arsenal. -

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume I 3 Stockpile

3 Stockpile Chapter Three USNuclear Stockpile This section describes the 24 types of warheads cur- enriched uranium (oralloy) as its nuclear fissile material rently in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. As of 1983, the total and is considered volatile and unsafe. As a result, its number of warheads was an estimated 26,000. They are nuclear materials and fuzes are kept separately from the made in a wide variety of configurations with over 50 artillery projectile. The W33 can be used in two differ- different modifications and yields. The smallest war- ent yield configurations and requires the assembly and head is the man-portable nuclear land mine, known as insertion of distinct "pits" (nuclear materials cores) with the "Special Atomic Demolition Munition" (SADM). the amount of materials determining a "low" or '4high'' The SADM weighs only 58.5 pounds and has an explo- yield. sive yield (W54) equivalent to as little as 10 tons of TNT, In contrast, the newest of the nuclear warheads is the The largest yield is found in the 165 ton TITAN I1 mis- W80,5 a thermonuclear warhead built for the long-range sile, which carries a four ton nuclear warhead (W53) Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) and first deployed equal in explosive capability to 9 million tons of TNT, in late 1981. The W80 warhead has a yield equivalent to The nuclear weapons stockpile officially includes 200 kilotons of TNT (more than 20 times greater than the only those nuclear missile reentry vehicles, bombs, artil- W33), weighs about the same as the W33, utilizes the lery projectiles, and atomic demolition munitions that same material (oralloy), and, through improvements in are in "active service."l Active service means those electronics such as fuzing and miniaturization, repre- which are in the custody of the Department of Defense sents close to the limits of technology in building a high and considered "war reserve weapons." Excluded are yield, safe, small warhead. -

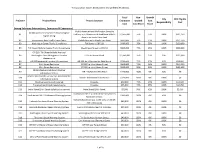

Draft Project List 2017-04-24

Transportation System Development Charge (TSDC) Project List Total Non- Growth City SDC Eligible Project # Project Name Project Location Estimated Growth Cost Responsibility Cost Cost Cost Share Share Driving Solutions (Intersections, Extensions & Expansions) Molalla Avenue from Washington Street to Molalla Avenue/ Beavercreek Road Adaptive D1 Gaffney Lane; Beavercreek Road from Molalla $1,565,000 75% 25% 100% $391,250 Signal Timing Avenue to Maple Lane Road D2 Beavercreek Road Traffic Surveillance Molalla Avenue to Maple Lane Road $605,000 75% 25% 100% $151,250 D3 Washington Street Traffic Surveillance 7th Street to OR 213 $480,000 75% 25% 100% $120,000 D4 7th Street/Molalla Avenue Traffic Surveillance Washington Street to OR 213 $800,000 75% 25% 100% $200,000 OR 213/ 7th Street-Molalla Avenue/ D5 Washington Street Integrated Corridor I-205 to Henrici Road $1,760,000 75% 25% 30% $132,000 Management D6 OR 99E Integrated Corridor Management OR 224 (in Milwaukie) to 10th Street $720,000 75% 25% 30% $54,000 D7 14th Street Restriping OR 99E to John Adams Street $845,000 74% 26% 100% $216,536 D8 15th Street Restriping OR 99E to John Adams Street $960,000 80% 20% 100% $192,000 OR 213/Beavercreek Road Weather D9 OR 213/Beavercreek Road $120,000 100% 0% 30% $0 Information Station Warner Milne Road/Linn Avenue Road Weather D10 Warner Milne Road/Linn Avenue $120,000 100% 0% 100% $0 Information Station D11 Optimize existing traffic signals Citywide $50,000 75% 25% 100% $12,500 D12 Protected/permitted signal phasing Citywide $65,000 75% 25% 100% -

Nuclear Matters. a Practical Guide 5B

NUCLEAR MATTERS A Practical Guide Form Approved Report Documentation Page OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. 1. REPORT DATE 3. DATES COVERED 2. REPORT TYPE 2008 00-00-2008 to 00-00-2008 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Nuclear Matters. A Practical Guide 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Office of the Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of Defense (Nuclear REPORT NUMBER Matters),The Pentagon Room 3B884,Washington,DC,20301-3050 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S) 11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORT NUMBER(S) 12. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT Approved for public release; distribution unlimited 13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 14. ABSTRACT 15. SUBJECT TERMS 16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF: 17.