Musings-On-The-Mahatma-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Gandhian Economics- Beyond Money to Ethics Abstract 2019 Marks the 150Th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi

P: ISSN NO.: 2321-290X RNI : UPBIL/2013/55327 VOL-6* ISSUE-8* (Part-1) April- 2019 E: ISSN NO.: 2349-980X Shrinkhla Ek Shodhparak Vaicharik Patrika Gandhian Economics- Beyond Money to Ethics Abstract 2019 marks the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. As a political philosopher, he has inspired scores of individuals, but the same can be extrapolated to the field of Economics. Through this article, we try to construct and deconstruct the basic tenets of Gandhian Economics, and why it is important in the 21st Century. Keywords: Gandhian Philosophy, Satya, Ahimsa, Violence, Dalit, Swaraj. Introduction The significance of Mahatma Gandhi as a political and social th leader can hardly be underestimated. 2019 marked the 150 birth anniversary of the Mahatma, which was celebrated in multiple ways not just by the Government of India, but also abroad. Truly, the quote by Albert Einstein ―Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this Earth‖ holds significance till today. When it comes to the economy, it can be safely concluded that Gandhi never wrote a treatise on Economics nor read a lot in its subject matter. However, his followers, in particular JC Kumarappa coined the word ‗Gandhian Economics‘ by extrapolating his ideas into the realm of economics. It is important to understand that these ideals are derivations of core Gandhian philosophies, Satya (Truth) and Ahimsa (Non-violence). His early life and views were radically shaped during the first wave of Kalpalata Dimri globalization (1840-1929) characterized by the rise of steamships, Associate Professor, telegraph and railroads. -

Gandhian Economics

GANDHIAN ECONOMICS ANJARIA J.J. / Essay on Gandhian economics / 1945-1945;1 / Bombay 150 AWASTHI D.S.Ed. / Gandhian economic theory / 1987 / U.P. 190 BEPIN BEHARI / Gandhian economic phiosophy / 1963-1963;1 / Bombay 157 BHARATHI K.S. / Economic thought of Gandhi / 1995 / Nagpur 228 BOSE R.N. / Gandhian technique and tradition in industrial relations / 1956.1 / Calcutta 228 DANTWALA M.L. / Gandhism reconcidered / 1945.3-1945.3;3 / Bombay 64 DAS Amritananda / Foundations of Gandhian economics / 1979 / Bombay 146 GANDHI M.K. / Voluntary poverty Ed. Ravindra Kelekar / 1961-1961;3 / Ahmedabad 30 GANDHI M.K. / Man Vs. machine Ed. Anand T. Hingorani / 1966-1966;2 / Bombay 105 GEORGE RAMACHANDRAN S.K. & G. Eds. / Economics of peace. 1952 / 19523-19523;2 / Wardha 378 GREGG Richard / Which way lies hope? / 1952.2-1952.2;7 /Ahmedabad GUPTA Shanti Swarup / Economic philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi / 1994-1994;1 / New Delhi 350 JAI NARAIN / Economic thought of Mahatma Gandhi / 1991-1991;1 / Delhi 175 JHA Shiva Nand / Critical Study of Gandhian Economic thought / 1961-1961;1 / Agra 276 JOSHI P.C. / Mahatma Gandhi: the new economic agenda / 1996-1996;1 / New Delhi 250 KUMARAPPA J.C. / Gandhian economy & other essays / 1949-1949;1 / Wardha association 120 KUMARAPPA J.C. / Gandhian way of life / 1950 / Wardha 48 KUMARAPPA J.C. / Economy of permanence: A quest for social order based on non-violence / 1948.1- 109 1948.1;3-1948.2-1948.2;2 / Wardha KUMARAPPA J.C. / Planning for the people by the people / 1954-1954;1 / Bombay 155 KUMARAPPA J.C. / Non-violent economy & world peace / 1955;1-1955-1958; 2 / Wardha 106 RADHEY MOHAN.Ed. -

NDA Exam History Mcqs

1500+ HISTORY QUESTIONS FOR AFCAT/NDA/CDS shop.ssbcrack.com shop.ssbcrack.com _________________________________________ ANCIENT INDIA : QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS _________________________________________ 1. Which of the following Vedas deals with magic spells and witchcraft? (a) Rigveda (b) Samaveda (c) Yajurveda (d) Atharvaveda Ans: (d) 2. The later Vedic Age means the age of the compilation of (a) Samhitas (b) Brahmanas (c) Aranyakas (d) All the above Ans: (d) 3. The Vedic religion along with its Later (Vedic) developments is actually known as (a) Hinduism (b) Brahmanism shop.ssbcrack.com (c) Bhagavatism (d) Vedic Dharma Ans: (b) 4. The Vedic Aryans first settled in the region of (a) Central India (b) Gangetic Doab (c) Saptasindhu (d) Kashmir and Punjab Ans: (c) 5. Which of the following contains the famous Gayatrimantra? (a) Rigveda (b) Samaveda (c) Kathopanishad (d) Aitareya Brahmana shop.ssbcrack.com Ans: (a) 6. The famous Gayatrimantra is addressed to (a) Indra (b) Varuna (c) Pashupati (d) Savita Ans: (d) 7. Two highest ,gods in the Vedic religion were (a) Agni and Savitri (b) Vishnu and Mitra (c) Indra and Varuna (d) Surya and Pushan Ans: (c) 8. Division of the Vedic society into four classes is clearly mentioned in the (a) Yajurveda (b) Purusa-sukta of Rigveda (c) Upanishads (d) Shatapatha Brahmana Ans: (b) 9. This Vedic God was 'a breaker of the forts' and also a 'war god' (a) Indra (b) Yama (c) Marut shop.ssbcrack.com (d) Varuna Ans: (a) 10. The Harappan or Indus Valley Civilisation flourished during the ____ age. (a) Megalithic (b) Paleolithic (c) Neolithic (d) Chalcolithic Ans: (d) 11. -

Triveni Mandir

26 Havan Mantras AUM SHRI PRAJA PATAY SWAHAA TRIVENI MANDIR AUM SHRI AGNIYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI PRITHVEEYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI GAURIYAYA SWAHAA 2014 AUM SHRI GANAPATTIYAY SWAHAA AUM SURIYO JYOTIR JYOTIR WARCHO SWAHAA AUM AGNI JYOTIR JYOTIR WARCHO SWAHAA AUM BHOORBHUVAH SWAH, TATSAVITUR VARNAGYAM BHARGO DEVVASYAA DHEE MAHI DHEE YO YONA PRAACHODAJAAT SWAHAA (3) AUM SHRI VARUN AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI RUDRA AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI MARUT AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI VAAYU AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI LAKSHMI MAATA AAYAY SWAHAA AUM HRING SHRI SARASWATI AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI DURGA MAATA AAYAY SWAHAA AUM NAMO BHAGWATAY VASUSEVAAYAA SWAHAA AUM SHRI BRAHMANAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI VISHNUAY SWAHAA AUM NAMAH SHIVAAYAA SWAHAA AUM SHRI HANUMATAYAA SWAHAA AUM SHRI ISHTAA DEVAYAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI KUL-DEWATAAAY SWAHAA AUM SHRI SURYAADI NAW GRAHAA DEVTA AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SARVAY DEO AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SAVAY DEVI AAYAY SWAHAA AUM SAVAY PITRI SWAHAA AUM SARVAS MAI SARVA BEEJAAYAY SARVA BHOOTAATEANAY SWAHAA AUM NAMO NARAYAN AAYAY SWAHAA (3) AUM PURNA MEDAH, PURNA IDAM, PURNAT PURNA म煍जीवितं मे संदेशः। MU DAKSHYATAY, PURNASYA PURNAMAA DAAYAA PURNA majjīvitaṁ me saṁdeśaḥ. MEWAH VASHISHT YA TAY AUM PURNA AHUTI GUAM SHANTI SWAHAA. My Life is my Message Triveni Mandir 2014 - Morning Services Booklet 2 25 Opening prayer Aarti Gajananam Bhoota Ganadi Sevitam, Om Jai Jagadish Hare Swami Jaya Jagadish Hare Kapittha Jambu Phalasara Bhakshitam Bhakta janon ke sankat Daasa janon ke sankat Kshan me door kar Umasutam Shoka Vinasha Karanam Om Jai Jagadish Hare Namami Vighneswara Pada Pankajam Jo dhyave phal -

Gandhian Economics Is Relevant

Gandhian economics is relevant The Times of India, 2 Oct 2005, 0000 hrs IST, Pulin B. Nayak The writer is Director, Delhi School of Economics. In recent years there appears to have been a resurgence of interest in what may be called Gandhian economics. Gandhiji first enunciated some of these ideas about a hundred years ago. These are contained in his Hind Swaraj, written in 1908 during a voyage from London to South Africa. It was later published as a booklet. Gandhiji's economic ideas continued to evolve over the next four decades after he returned to India for good at the age of 45. He altered some of his more extreme positions on, say, machinery, but on a number of core formulations his conviction was unchanged. Even at the height of Gandhi's virtually unchallenged position during India's freedom struggle there were many within the Congress party, some of them his closest confidants, who were never impressed with his economic formulations. These included, notably, Jawaharlal Nehru and Jayaprakash Narayan. Nehru never challenged Gandhiji's overall moral and political pre-eminence, but his emphasis on heavy industry and investment planning was at variance with Gandhi's ideas. Hind Swaraj was a severe condemnation of modern civilisation. It aimed for self-rule in a context where the twin principles of satyagraha and non-violence were the core postulates. As one who had the most perspicacious understanding of the Indian countryside, Gandhi felt that the key to the country's progress lay in the strengthening of the decentralised, self-sufficient village economies. -

Ms Nabilam Gandhianeconomi

M.K.Gandhi was born on Oct 2, 1869, @ Porbander From 1893 to 1914 Gandhi rendered great service to the cause of racial equality in South Africa. His philosophy of passive resistence, as it was known then, against the unjust persecution of the Indians in South Africa won the hearts even of his opponents He served the people of South Africa for two decades and came back to India in 1915. In 1920 Gandhi started the non-cooperation movement. In 1930 he led the ‘salt satyagraha’( Dandi march) In 1919, he conducted the civil disobedience movement and 1942 he launched the Quit India movement On 30 January 1948 he was shot dead by an Indian, named Nathu Ram Godse ,who did not agree with his views on political matters HIS ECONOMIC IDEAS Gandhi did not believe in any definite scheme of economics thought. His economic ideas are found scattered all over his writings and speeches. To him,economics was a part of way of life and hence his economic ideas are part of his general philosophy of life Gandhi’s economic ideas are based on 4 cardinal principles: truth , nonviolence, dignity of labour, and simplicity. Gandhi said that the only means of attaining eternal happiness is to lead a simple life. He believed in the principle of ‘simple living and high thinking’ He was an apostle of non-violence, and his economics may be called as economics of non-violence. The principle of non-violence is the soul of Gandhian philosophy. He believed that violence in any form will not bring any kind of peace because it breeds greater violence. -

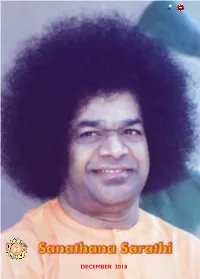

December 2018

DECEMBER 2018 S a n a t h a n a S a r a t h i Devoted to the Moral and Spiritual Uplift of Humanity through SATHYA DHARMA SANTHI PREMA AHIMSA Vol.: 61 Issue No. 12 Date of Publication: 5th December “Do you need a special time to December 2018 think of God? You can think © Sri Sathya Sai of God all the time you are Sadhana Trust, Publications Division Prasanthi Nilayam discharging your duties. Let Printed by K.S. RAJAN your every thought be of God. Published by K.S. RAJAN On behalf of the owner, Sri Sathya Sai See all work as God’s work, Sadhana Trust, Publications Division, Prasanthi Nilayam 515134, Anantapur District (A.P.) feel every place you go to as the And Printed at M/s Rajhans Enterprises, 136, 4th Main Road, Industrial Town, Rajaji Nagar, temple of God. If you think Bengaluru 560044, Karnataka like this, you will have no need And Published at Sri Sathya Sai Sadhana Trust, Publications Division, Prasanthi Nilayam to worry about time.” 515134, Anantapur Dist., Andhra Pradesh. Editor G.L. ANAND C O N T E N T S Assistant Editor P. RAJESH E-mail: [email protected] 4 Promote the Welfare of Others [email protected] For Audio Visual / Bhagavan’s Discourse: 2nd May 1997 Book Orders: [email protected] ISD Code : 0091 9 International Spiritual Conference on STD Code : 08555 Telephone : 287375 “Living with Sri Sathya Sai” Sri Sathya Sai Central Trust Telefax : 287390 A Report Sri Sathya Sai University - Administrative Office : 287191 / 287239 13 Living Under the Benevolent Care of Swami Sri Sathya Sai Higher Secondary School : 289289 Nidadavolu Suri Babu Sri Sathya Sai Primary School : 287237 15 It is the Same Baba in Shirdi SSSIHMS, Prasanthigram, Puttaparthi : 287388 Padmamma SSSIHMS, Whitefield, Bengaluru : 080 28411500 17 37th Annual Convocation of Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning Annual Subscription A Report acceptable for 1, 2 or 3 years. -

Syllabus Gandhi V2.Pdf

Gandhi and the Politics of Resistance Neil Desai Course Name: Politics of Resistance: the Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi Instructor: Name: Neil Desai Email: [email protected] Phone: 347-833-1178 Office Hours: By appointment Course Description in SIS/Introduction to the Class ! Political resistance has exploded over the past few years, spreading from Ben Arous and Tahrir Square to Jantar Mantar, Zuccotti Park, Puerta de Sol, Euromaidan, Ferguson, and most recently to our very own Rotunda. This course will take us back to where it all started, and explore the ideas of the man who, more than any other, was responsible for inventing Civil Disobedience. This will not, primarily, be a class on Gandhi’s life. Instead, we will examine the original writings of both Gandhi and some of his major contemporaries to better understand what civil disobedience is, what it is not, in what historical contexts it has been effective, and how it is still relevant today. Required Texts: All readings are available for free online. They can be accessed via the links provided in the course schedule. Students who prefer a paper copy can also find some of them in the library. Course Expectations: • The Code of Honor of the University of Virginia reads as follows: “On my honor, I pledge that I will not lie, cheat, or steal.” Students are expected to adhere to this code at all times, both inside and outside of class. It is especially important considering the nature of our subject matter, and students are encouraged to relate material from the class to their day-to-day experience as a member of our Community of Trust. -

Indian Premier Modi Tweets Praises for Bahrain

TWITTER CELEBS @newsofbahrain NEWS OF BAHRAIN 4 VIVA primed for further digital transformation INSTAGRAM Ariana Grande splits /nobmedia 16 from fiance LINKEDIN TUESDAY newsofbahrain OCTOBER 2018 Singer Ariana Grande and “Saturday Night Live” star WHATSAPP 200 FILS 38444680 ISSUE NO. 7901 Pete Davidson have called off their engagement. FACEBOOK /nobmedia The couple ended their engagement over the MAIL [email protected] weekend, TMZ reported on Sunday. WEBSITE newsofbahrain.com P13 Prince Harry and Meghan expecting their first baby 7 WORLD BUSINESS 11 Arcapita invests in Saudi women’s fitness chain Consensus on CR fees hike TDT | Manama he Chairman of the Bah- Inspect labour camps Train Chamber of Com- merce and Industry (BCCI) Sameer Nass yesterday said Strict legal action against providing substandard accommodation facilities to labourers that following lengthy discus- sions with the government officials a consensus was The directive follows reached, according to which • the fees for new Commercial the building collapse Registrations will be BD50 in the Salmaniya area with BD100 for up to three ac- last Tuesday, leaving tivities, while additional busi- four dead and more ness activities will be charged BD 100 each. than 30 injured. Mr Nass explained that the initial proposal of the cham- HRH the Premier ber was to keep the new fees reviewed• the steps within the range of neigh- taken by the ministries bouring Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries at of Labour and Social BD100 for new Commercial Development, the HRH the Premier chairs the Cabinet. Registrations and BD75 for Interior, Works, the renewal. Municipalities Affairs Municipalities Affairs and Urban The building, which was home Among other things, the session tation for two six-month periods He explained that the Planning to conduct frequent in- to over 170 labourers, collapsed welcomed Bahrain’s election as until the two sides reached an Chamber had formed an ac- and Urban Planning and spections to all labour accommo- following a gas cylinder blast. -

Exploring Gandhian Ideology for Sustainable Rural Development in India

Journal Global Values Vol- VII, No. 1, 2016 ISSN (P): 0976-9447, (e): 2454-8391 ICRJIFR, IMPACT FACTOR 3.8741 Exploring Gandhian Ideology for Sustainable Rural Development in India Meenu Sharma* Research Scholar Department of History Meerut College, Meerut & Shikha** Research Scholar Department of History Meerut College, Meerut Abstract: India has achieved a remarkable sustainable socio-economic development since Independence. Unfortunately, this development has not been shared equitably by all. Some sections of the society have been left out and some areas like rural, tribal and remote areas, could not keep pace with the urban areas in development. If vast sections of society and areas are left out, it breeds unrest and is not conducive to a sustainable development of the country. Communication strategies of various types have been developed and used for motivating people and increase their participation in the pathway for rural development. The R&D organizations interested in accelerating the process of social change through communication of innovations have their goal in which the participatory process is expected to make the rural audience the makers of their own destiny. Participation and empowerment have thus gained wide currency in recent development literature, as if the ideas that people at the grass roots level are the real flag bearers have been discovered only today. People do act, it is for us to appreciate it and materialize it for participatory people- centric movements. Gandhi, as a development actor emerged long ago in the vision and action at Wardha. Gandhi being a national political leader had basically relied on mobilization of the masses and their economic uplift through the development of cottage and small scale industries. -

''The Mahatma Is Our Past, He Is Our Present and He Is Also Our Future.'' Gandhi Strived to Lead the Country to Not

THE ORCHID SCHOOL SECONDARY AND SENIOR SECONDARY DOMAIN, 2020-2021 THEME ACTIVITY FOR THE MONTH OF JUNE ‘’The Mahatma is our past, He is our present and He is also our future.’’ Gandhi strived to lead the country to not just political independence, but to a better India and a society free of caste, religious, economic and even gender prejudices. He was the inspiration for our largely non-violent, inclusive and democratic freedom struggle. He continues to remain the ethical benchmark, against which we test our political ideas, government policies, and the hopes and wishes of our country men. The world needs to invoke his ideas in the building of the 21st century that is marked by justice and equality, by incorporating global peace and wisdom. Gandhi is revered, not only for his contributions as a freedom fighter, but also for conceptualizing and providing a new way to deal with injustice and oppression. He was an exponent of non- violence or Ahimsa and provided a unique philosophy, based on truth and non-violence as a guide to lead one’s life. Ahimsa is nothing but love, and love is that energy which cleanses our inner life and uplifts our thoughts. Such love perpetuates noble feelings like benevolence, compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, generosity, kindness, sympathy, etc. Young minds are the best assets a country can have and by using the power of ideas, they can lead us towards a New India, an India that has the best of education, health and technology, among others. Gandhi was a strong proponent of India where young minds lead the country to greater heights, India free from hunger, poverty and discrimination.