Paper-Making Materials and Their Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCCASION This Publication Has Been Made Available to the Public on The

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] I DM •JlStr. I 1 / V | \ J LIMITED ID/wG.352/1 7 October 193' United Nations Industrial Development Organization ENGLISH International Experts Group Meeting, on Pulp and Paper Technology Manila, Philippines, 3 - 8 November 1980 THE PHILIPPINE PULP AND PAPER INDUSTHT* by Vicente 0. -

Predicting the Future Illustrated Art Lessons

Predicting the Future Illustrated Art Lessons Drawing Storyboards Materials: 12" x 18" manila paper • pencils • erasers • colored markers or tempera paint and paintbrushes 3. Carefully think through the events that may have led up to the scene in the focus work. Draw those events in sequential order, beginning with the first box. 1. To divide the paper into eight rectangles, fold it in half horizontally, then fold it in half again parallel to the first fold. Unfold the sheet and fold it in half vertically. When opened, the fold lines will form eight rectangles. 4. Imagine the events that followed the scene in the focus work, then sketch them in sequential order. 2. Lightly sketch the focus work of art in the fourth or fifth rectangle. 5. Use paint or markers to complete the drawings and add expression. Unify the storyboard by repeating colors. The Learning Through Art program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is underwritten by: The Learning Through Art curriculum website is made possible in part by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. 17.285 Predicting the Future Illustrated Art Lessons Constructing a Family Tree Materials: 12" x 18" white paper • smaller sheets of manila or white paper • colored pencils • glue • scissors 1. Draw a full-length self-portrait about 6 inches tall. Include as many details as possible to show hair color, eye color, and other distinctive features. 4. Construct the family tree on a 12" x 18" sheet of white paper. Paste the self-portrait at the bottom of the page. -

Proposed Roadmap for the Paper Industry in Philippines

ROADMAP FOR THE PAPER INDUSTRY IN PHILIPPINES (2014-2020) _________________________________________ Ray N. Geganto Exec. Director Philippine Paper Manufacturers Association Inc. (PPMAI) formerly Pulp &Paper Manufacturers Assoc. of the Phils. (PULPAPEL) The Phil. Paper Manufacturers Assoc. Inc. (PPMAI): (formerly Pulp and Paper Assoc. of the Phils.(PULPAPEL) MEMBERS MILLSITE 1. Trust International Paper Corp. (TIPCO) Mabalacat, Pampanga 2. United Pulp and Paper Co. (UPPC) Calumpit, Bulacan 3. Bataan 2020 Inc. Samal, Bataan; Baesa, Q.C. 4. Container Corp. of the Phils. (CCP) Balintawak, Q.C. 5. Noahs Paper Mill, Inc. Marikina 6. Liberty Paper Inc. Valenzuela City 7. Paperland, Inc. Balintawak, Q.C. 8. Fiber Sorting Inc. Pampanga 9. Asia Paper Ind. Corp. Trece Martires, Cavite 10.St. Thomas Paper Corp. Sto. Tomas, Batangas 11. Hansson Paper Phils. Corp. Pasig, NCR 12. Vanson Paper Ind. Corp. Valenzuela, NCR What is Paper and Paperboard? Paper Industry in Phils. -Current State and Background 2001 2010 2012 Historical Est. Trend % p.a. No. of Paper Mills 43 27 24 Industry Capacity, ‘000 Tons 1,580 1,297 1,200 -2.2% Production 1,056 1,038 825 -2% Imports 533 961 1,100 +9.5% Exports 139 165 110 -2% CONSUMPTION 1,450 1,834 1,810 +2.2% Paper &Board per Capita 16 20 19 +2% Consumption Paper Mills remaining in Operation (2012) 1. Trust International Paper Pampanga Newsprint, Printing &Writing 2. United Pulp and Paper Bulacan Containerboards 3. Bataan 2020 Bataan, Q.C. Pr &Wr, Containerboards,Bag paper 4. Container Corp. of Phils. Quezon City Containerboards, Cartonboard 5. Noahs Paper Mill Marikina Pr &Wr, Bag paper 6. -

Changes in Print Paper During the 19Th Century

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Charleston Library Conference Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century AJ Valente Paper Antiquities, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/charleston An indexed, print copy of the Proceedings is also available for purchase at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston. You may also be interested in the new series, Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences. Find out more at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston-insights-library-archival- and-information-sciences. AJ Valente, "Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century" (2010). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314836 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. CHANGES IN PRINT PAPER DURING THE 19TH CENTURY AJ Valente, ([email protected]), President, Paper Antiquities When the first paper mill in America, the Rittenhouse Mill, was built, Western European nations and city-states had been making paper from linen rags for nearly five hundred years. In a poem written about the Rittenhouse Mill in 1696 by John Holme it is said, “Kind friend, when they old shift is rent, Let it to the paper mill be sent.” Today we look back and can’t remember a time when paper wasn’t made from wood-pulp. Seems that somewhere along the way everything changed, and in that respect the 19th Century holds a unique place in history. The basic kinds of paper made during the 1800s were rag, straw, manila, and wood pulp. -

Home & Garden Fair GENERAL RULES

Home & Garden Fair GENERAL RULES 2015-2016 Home & Garden Fair Mandy Patrick - Chairperson DIVISIONS Photography Art Elementary Art Horticulture Foods Canning Crafts Woodworking Quilts (Adults Only) ELIGIBILITY 1. The Home & Garden Fair is open to all residents of Houston County. 2. ENTRY FEES per Entry: Elementary Art – all grades K through 6th - $1.00. ALL OTHER ENTRIES: Youth (3rd-12th grades), $2.00, Adults $3.00 GENERAL RULES 1. All exhibits must be the work of the contestant and may not have been entered in previous Houston County Fairs. All Home & Garden Project entries must have been made in 2015-2016 and must be completed. 2. All entries except BAKED GOODS & QUILT ENTRIES are to be brought to the CIVIC CENTER on TUESDAY, April 5th, between the hours of 6:00-8:00 p.m. 3. BAKED GOOD ENTRIES are to be brought to the CIVIC CENTER on WEDNESDAY, April 6th, between the hours of 8:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. 4. Exhibitors may enter as many items in a class/category as desired except in Photography (limited to 4 items per class), provided entry fee is paid for EACH exhibited item. 5. QUILTS should be brought to the Houston County Extension Office by 3:30pm on the Tuesday of Fair Week. 6. All exhibits on display must be clearly labeled with the NAME, ADDRESS, TELEPHONE NUMBER, AND SCHOOL (IF APPLICABLE) of the contestant. Labels should be placed on the BACK of the article. 7. The Civic Center will be closed from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. -

Paper Packaging Industry

Industry Structure and Competitiveness PAPER INDUSTRY Introduction In the manufacture of paper-based packaging, the following paper products are used: kraftliner/sack kraft paper, multi-ply paper and paperboard, corrugating medium, and corrugated paper. The attached linkage chart shows the flow of commodities from the raw materials to paper-based packaging (see Figure 1). The production process from raw materials to finished cartons and boxes is as follows: ➲ Pulp and waste paper preparation – involves sorting, handling and feeding of fiber and old carton/paper into the stock line. ➲ Stock preparation- involves pulping, steaming, screening, refining and blending of different grades of raw materials. ➲ Filler and additives preparation – involves the storing, diluting and feeding of rosin, alum and dye to the pulp stock in the machine chest. ➲ Board forming – involves the final screening, pressing (removal of water), drying and surface sizing of the board. ➲ Finishing – involves the winding, and slitting of rolls to the desired trim size and roll diameter before storing in the warehouse. The objective of this study is to provide a competition analysis of the paper industry which serves as input to the paper-based packaging industry, using an analytical framework specifically developed for this purpose, and to make recommendations, if necessary, on how to make the industry competitive or improve its competitiveness. It is hypothesized that to improve the input sectors of the Philippine export industry will translate into competitiveness or better competitiveness of Philippine exports. The packaging industry is critical to the export sector since high-quality and sophisticated packaging is a requirement for success in the global market. -

Paper Manufacturing Industry-223067-.Pdf

www.entrepreneurindia.co Introduction Paper is one of the basic needs of modern life. It is a well-known product, which is the only media of communication through writing. It is used in every part of life, i.e., education, office, researches, engineering, art, book printing, magazine, newspaper, etc. Paper is an important material, used daily for many purposes worldwide. Used in a wide variety of forms, paper and paperboard are characterized by a wide range of properties. www.entrepreneurindia.co Papers are used for writing purpose and printing purpose. Books are created using papers and newspapers etc. Now most of them used computers for creating notes but if computer get damaged also disappeared, where the note in paper permanent and reading is a good habit and its increase our knowledge level, reading lots of book is good habit but Reading things in computer decrease power of eye. Papers are made from some kind of trees. www.entrepreneurindia.co Uses and Applications: Media Kraft Paper: This is used in corrugated box manufacturing and by all the industrial packaging units. The main market lies in Chennai, Madurai, Coimbatore, Virudhunagar and Sivakasi. Plain/Ribbed Kraft Paper: This is used as wrappers for books and notebooks and also in all packaging industries. White Poster and Color Poster: These are consumed by the printing presses for wall posters and also for printing tickets, vouchers, etc. The main market is at Chennai and Sivakasi where there number of printing presses exist. www.entrepreneurindia.co Manila paper: This is made out of No.1 white cutting, used for making envelopes and will be marketed in Chennai and Sivakasi. -

Art Activity & Appreciation Kits

Fairbanks North Star Borough School District Artwork by Austin Cain Revised July 2019 Distributed By: and the Department of Teaching & Learning Art Center Location: Ryan Middle School 1450 Cowles Street Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Phone: (907) 328-0701 option 1 Art Center Fax: (907) 456-2594 Art Center Website: http://www.k12northstar.org/ArtCenter To Search for Art Kits in Destiny: http://destiny.k12northstar.org For Art Kit Checkout Instructions: http://www.k12northstar.org/Page/2530 Fairbanks North Star Borough School District i 2019 – 2020 Art Kit Catalog Introduction About the Kits ............................................................................................................................................ iii NEW Kits for 2019 – 2020! ....................................................................................................................... iv Elementary Grade – Level Artists............................................................................................................... v Alaska Native Artists ................................................................................................................................. vi Art Kit Support Supply List ...................................................................................................................... vii Art Kits Kindergarten ............................................................................................................................................... 8 First Grade ............................................................................................................................................... -

Kaufman School Supplies 2020-2021

School Supplies Kaufman Elementary School Conroe Independent School District 2020 2021 Kindergarten - No rolling backpacks Manila paper (12”x 18”, 50 count) .........................................................1 pkg. Paper (colored, card stock, boys only) ..........................................................1 Pocket folder (plastic, 1 each red and blue) ................................................... 2 Paper (white, card stock, girls only) ..............................................................1 Plastic school box (large size).......................................................................1 Copy paper (colored, boys only) ..........................................................1 pkg. Pocket folders (w/brads, 1 each green, yellow, orange) ................................. 3 Copy paper (500 sheets/ream, white, 8.5”x11”) ............................................1 Red grading pens ..................................................................................... 2 Construction paper (assorted colors, 9”x12”, 50 count) ...........................1 pkg. Glue stick (large, .77 oz) ............................................................................ 8 Manila paper (9”x12”, 50 count) ...........................................................1 pkg. Ziploc bags (quart size—boys only, gallon size—girls only)........................1 box Pocket folder (plastic, w/prongs, 1 each green and red) ................................ 2 Binder (1⁄2”, white) .....................................................................................1 -

Nesmith Elementary School Supply List 18-19 Pre-K Kindergarten 2 Facial Tissue 100 Ct

NeSmith Elementary School Supply List 18-19 Pre-K Kindergarten 2 Facial Tissue 100 ct. 20 Pencils #2 2 Crayola Crayons 24 ct. 6 Crayola Crayons 24 ct. 2 Expo Markers 2pk (any color) Dry Erase (girls) 1 5" Blunt Scissor 4 Elmer's Glue Stick (small) 10 Elmer's Glue Stick (small) 2 Gallon ziploc bags (slide top preferred) (boys) 1 Pink Bevel Eraser 1 Washable Watercolor Paints w/ brush 1 Plastic School Box 1 Crayola Large Tip Washable Markers 4 Black Expo2 Low Odor Chsl Tip Dry Erase 1 Crayola Super Tips thin tip Washable Markers 2 Blue Plastic Pocket & Brad Folder 3 Plastic Pocket folder w/ Brads 2 Composition Book 1 12X18 Manila Paper 50 ct. (Boys) 2 Dixie Cups 100 ct. 3 oz. 1 9X12 Colored Construction Paper 50 ct. (girls) 2 Mead Marble Comp w/story paper rd Bsline 100 ct. (Primary) 1 Plastic School Box 2 5 oz. cans of Play-Doh 1 4 Color Pk Play Doh (5oz. Cans) 1 Washable Markers Broad Tip 3 Marble Comp w/story paper 100 ct.(Primary) 2 Facial Tissue (100 ct.) 1 Babywipes 80 ct. 2 Elmer's Glue All 4 oz. 2 Hand Sanitizer w/pump 8 oz. 1 Headphones (no earbuds) 2 Lysol Disinfecting Wipes (boys) 1 12X18 Manila Paper 50 ct. 2 Plastic Cups - 12 oz. (girls) 1 gallon ziploc bags (slide top preferred) 2 Coffee Filters (used for snack "plates") 1 spill-proof/spout top refillable water bottle 1 Box of Sidewalk Colored chalk (girls) 1 Babywipes 80 ct. 1 Box of Colored chalk (thin) (boys) 1 Hand Sanitizer w/pump 8 oz. -

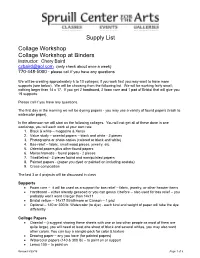

Supply List Collage Workshop Collage Workshop at Binders

Supply List Collage Workshop Collage Workshop at Binders Instructor: Chery Baird [email protected] (only check about once a week) 770-448-5000 - please call if you have any questions We will be creating approximately 6 to 10 collages; if you work fast you may want to have more supports (see below). We will be choosing from the following list. We will be working fairly small; nothing larger than 14 x 17. If you get 2 hardboard, 2 foam core and 1 pad of Bristol that will give you 19 supports. Please call if you have any questions. The first day in the morning we will be dyeing papers - you may use a variety of found papers (trash to watercolor paper). In the afternoon we will start on the following collages. You will not get all of these done in one workshop, you will each work at your own rate. 1. Black & white – magazine & Xerox 2. Value study – oriental papers – black and white - 2 pieces 3. Photographs or photo copies (colored or black and white) 4. Bas-relief – fabric, small wood pieces, jewelry, etc. 5. Oriental papers plus other found papers 6. Monochromatic - found papers - 2 pieces 7. Triad/tetrad - 3 pieces found and manipulated papers 8. Painted papers - (paper you dyed or painted on including acetate) 9. Cross-composition The last 3 or 4 projects will be discussed in class Supports Foam core – it will be used as a support for bas relief – fabric, jewelry, or other heavier items Hardboard – either already gessoed or you can gesso it before – also used for bas relief – you probably won’t want it larger than 14x11 Bristol vellum – 14x17 Strathmore or Canson – 1 pad Optional – 140 or 300 lb. -

Evolution of a Paper Co~Wany: the Carlisle-Ferguson Years at St. Regis

EVOLUTION OF A PAPER CO~WANY: THE CARLISLE-FERGUSON YEARS AT ST. REGIS Interviews with 'c, "• Homer A. Vilas and James E. Kussman;' conducted by " , /' ,., Elwood R. Maunder and John R. Ross and"appen~ded -inte-rview with '.~ ,Carl B. ,Martin James E. Kussmann and Samuel Shane Forest History Society - Santa Cruz, California 1977 -, ,'. - .. ·.--.P '. .... ~ This volume is second in a series of or~l histor£~s on St. Reg4s Paper Company. The·~irit volu,me,. THREE MEMOIRS ON ST. REGIS PAPER COMPANY RI~.T6RY (Eunice Remington 'Nardwell, Louise E .. ·. Richter, and' Harold S. Sutton), was published i.n 1976. '-. ,. "," Forest History Society, Inc. P. O. Box 1581 Santa Cruz, California 95061 Copyright ©1977 by Forest History Society, Inc. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . vii INTERVIEW I: H01ffiR A. VILAS, DECEMBER 8, 1975 NEW YORK, NEW YORK . 1 First encounter with Roy K. Ferguson in 1921;. F. L. Carlisle and Company; Ferguson, Carlisle, and the pre-Depression business world; St. Regis during the Depression; Sandy Calder and Union Bag and Paper Company; Remarks on the brokerage business; Charles E. Norris, H. Edmund Machold, and Al Smith; Ferguson's relationship with Carlisle; contemplated merger of St. Regis with Union Bag and Paper Company; F_e]guson' s leader-' ,.--'--~ --"-~ .:::~. ----.~-_.- -,,- - - ',- ,.. _,,- ',- . .-'/ - ';,- .. ,,-"'--- - .. - .. sh-ip a'tSt.· Regis';-· tile pe;rsonal)Vorld of, Roy K. Ferguson'---religioiis-'faith, familY-; -and p-astimes; reflections on Ferguson as a friend. INTERVIEW II: JAMES E. KUSSMANN, OCTOBER 17, 1975 ,fJEWYOBK; NEW YORK . 31 Session 1: Roy K. Ferguson takes charge of St. Regis in 1934; separation of papermaking and public utilities interests; the company during the wartime period--1939~1945; postwar expansion in printing papers and the move to the South; impacts of World War II; St.