The Silent Integration of Refugees on the Zambia-Angolan Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellow Fever Outbreak in Angola, 01 September 2016

YELLOW FEVER OUTBREAK WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT, INCIDENT MANAGEMENT TEAM—ANGOLA YELLOW FEVER OUTBREAK IN ANGOLA INCIDENT MANAGEMENT Vol: 8-03 SITUATION REPORT W35, 01 September 2016 I. Key Highlights A total of 2,807,628 (94 %) individuals 6 months and above have been vaccinated in the 22 most recently vaccinated districts as of 01 September 2016, 15 districts out of 22 achieved 90% or more of vaccination coverage. 4 districts achieved between 80-90%. Three districts did not reach 80% coverage and the vaccination campaign was extended there for another one week : Dirico, Namacunde and Sumbe in Currently the IM System is supporting the Ministry of Health in the preparation of the upcoming campaign in 21 districts in 12 provinces. The total population targeted in this new phase is 3,189,392 and requires 3,986,019 doses of vaccines. Is expected the arrival of 1.98 M doses from the last request approved by ICG. The ICG did not communicate yet the date of shipment but is already on process. The preparation of the coverage survey is ongoing. Table 1: National Summary of Yellow Fever Outbreak II. Epidemiological Situation as of 01 September 2016 Yellow Fever Outbreak Summary 26 Aug — 01 Sep 2016, (W35) Reported cases 24 Samples tested 24 Week 35 statistics (26 August to 1 September 2016): Confirmed cases 0 Of 24 suspected cases reported, all of them were tested by the National Total Deaths 1 Laboratory. None of them was positive for yellow fever Total provinces that reported cases 8 One(1) death was reported among the suspected cases during this period. -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

Floods; MDRAO002; Operations Update No. 1

Emergency Appeal MDRAO002 \ GLIDE no. FF-2007-000020-AGO ANGOLA: FLOODS 22 June 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief Appeal no. MDRAO002; Operations Update no. 1; Period covered: 29 January to 31 March 2007 (This update covers activities implemented using DREF support). Appeal coverage: 27.3%; Outstanding needs: CHF 1,029,252 (USD 836,790 or EUR 623,789). <Click here to go to the attached interim financial report> Appeal history: • Emergency Appeal was launched 23 February 2007 for CHF 1,416,264 (USD 1,133,011 or EUR 874,237) for three months to assist 30,000 beneficiaries (5,000 households). • Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: CHF 90,764 (USD 855,061 or EUR 639,771). For the DREF Bulletin, please refer to: http://www.ifrc.org/docs/appeals/06/MDRAO002.pdf Related Emergency Appeal: Appeal no. MDRAO001 (Angola: Cholera) Operational Summary: On 29 January 2007, the Federation allocated CHF 90,764 from its Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Angola Red Cross in responding to the needs of people affected by floods in Luanda. Following another spate of flooding in Moxico Province, the Federation launched an Emergency Appeal for CHF 1.4 million to assist 5,000 households for three months. Due to increased needs in Moxico, available relief items and funds were reallocated from Luanda and the two operations were merged. -

Working Papers Moving from War to Peace in the Zambia–Angola Borderlands

Working Papers Paper 63, November 2012 Moving from war to peace in the Zambia–Angola borderlands Oliver Bakewell This paper is published by the International Migration Institute (IMI), Oxford Department of International Development (QEH), University of Oxford, 3 Mansfield Road, Oxford OX1 3TB, UK (www.imi.ox.ac.uk). IMI does not have an institutional view and does not aim to present one. The views expressed in this document are those of its independent author. The IMI Working Papers Series IMI has been publishing working papers since its foundation in 2006. The series presents current research in the field of international migration. The papers in this series: analyse migration as part of broader global change contribute to new theoretical approaches advance understanding of the multi-level forces driving migration Abstract This paper explores the changing relationship between the people of North-Western Zambia and the nearby border with Angola, focusing on the period as Angola has moved from war to peace. Drawing on research conducted between 1996 and 2010, the paper examines how people’s interactions with the border have changed, focusing on their cross-border livelihoods, identities and mobility. With the end of the war and the rehabilitation of the formal border crossing, legal restrictions and practical obstacles to movement have relaxed; at the same time, the conventions – based on informal, ‘illicit’ understandings between local officials and inhabitants on both sides of the border – that operated for many years have been undermined. Hence, there has simultaneously been both an ‘opening’ and ‘closing’ of the border. Moreover, the breaking of these conventions since the end of the war has reduced the size of the zone of informal exchange and hybridity, or borderlands. -

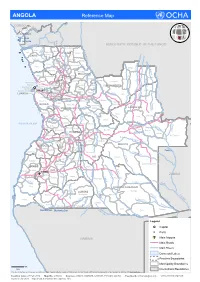

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Suma Rio Presidente Da Repubuca

Ter~a-feira, 25 de Fevereiro de 2014 I Serie-N.0 38 ORGAO OFICIAL DA REPUBLICA DE ANGOLA Pre~o deste numero- Kz: 430,00 Toda a correspondencia, quer oficial, quer ASSINATURA 0 pre90 de cada linha publicada nos Diarios relativa a anfulcio e assinaturas do «Diario Ano da Republica !.' e 2.' serie e de Kz: 75.00 e para da Republica», deve ser dirigida a Imprensa As tres series ................... Kz: 470 615.00 a 3.' serie Kz: 95.00, acrescido do respectivo Nacional • E.P., em Luanda, Rua Henrique de A!.' serie ................... Kz: 277 900.00 imposto do selo, dependendo a publica9ao da Carvalho n. 0 2, Cidade Alta, Caixa Postal 1306, www.imprensanacional.gov.ao • End. teleg.: A 2.' serie .... Kz: 145 500.00 3.'seriededep6sitoprevioaefectuarnatesouraria «Imprensa». A 3.' serie ... Kz: 115 470.00 da Imprensa Nacional - E. P. ARTIGO 2. 0 SUMA RIO (Revoga~ao) Presidente da Republica E revogada toda a legisla~ao que contrarie o disposto no presente Diploma. De creto Presidencial n. 0 46/14: 0 Aprova o Programa deAc9ao Nacional de Combate a Desertifica9ao. - ARTIGO 3. Revoga toda a legisla9ao que contrarie o disposto no presente Diploma. (Ditvidas e omissoes) As duvidas e omissoes resultantes eta inte1:preta~a o e apli Ministerio da Agricultura ca~ao do presente Decreto Presidencial sao resolvidas pelo Despacho n. 0 433/14: Presidente da Republica. Exonera Filomena Tavares de Almeida da Costa do cargo de Chefe de ARTIGO 4. 0 Sec9~0 de Tesoura1ia do Fundo de Desenvolviment.o do Cafe de Angola. (Entrada em vigor) Despacho n. -

Angola Livelihood Zone Report

ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………................……….…........……...3 Acronyms and Abbreviations……….………………………………………………………………......…………………....4 Introduction………….…………………………………………………………………………………………......………..5 Livelihood Zoning and Description Methodology……..……………………....………………………......…….…………..5 Livelihoods in Rural Angola….………........………………………………………………………….......……....…………..7 Recent Events Affecting Food Security and Livelihoods………………………...………………………..…….....………..9 Coastal Fishing Horticulture and Non-Farm Income Zone (Livelihood Zone 01)…………….………..…....…………...10 Transitional Banana and Pineapple Farming Zone (Livelihood Zone 02)……….……………………….….....…………..14 Southern Livestock Millet and Sorghum Zone (Livelihood Zone 03)………….………………………….....……..……..17 Sub Humid Livestock and Maize (Livelihood Zone 04)…………………………………...………………………..……..20 Mid-Eastern Cassava and Forest (Livelihood Zone 05)………………..……………………………………….……..…..23 Central Highlands Potato and Vegetable (Livelihood Zone 06)..……………………………………………….………..26 Central Hihghlands Maize and Beans (Livelihood Zone 07)..………..…………………………………………….……..29 Transitional Lowland Maize Cassava and Beans (Livelihood Zone 08)......……………………...………………………..32 Tropical Forest Cassava Banana and Coffee (Livelihood Zone 09)……......……………………………………………..35 Savannah Forest and Market Orientated Cassava (Livelihood Zone 10)…….....………………………………………..38 Savannah Forest and Subsistence Cassava -

Boletim Da SOCIEDADE PORTUGUESA De ENTOMOLOGIA

ISSN 0870-7227 Boletim da SOCIEDADE PORTUGUESA de ENTOMOLOGIA Vol. VIII-14 Bolm Soc. Port. Ent. N.º 228 2013.07.31 GAZETTEER OF THE ANGOLAN LOCALITIES KNOWN FOR BEETLES (COLEOPTERA) AND BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA: PAPILIONOIDEA) LUIS F. MENDES(1), A. BIVAR DE SOUSA(2), R. FIGUEIRA(3), & ARTUR R.M. SERRANO(4) Resumo: Apresenta-se uma lista de localidades de Angola de onde se tem conhecimento de se terem capturado coleópteros (Coleoptera) e lepidópteros diurnos (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea). Para cada localidade são indicadas a Província administrativa, e as longitude, latitude e altitude aproximadas, assim como o número da correspondente carta de levantamento aero-fotogramétrico na escala de 1:100 000. Quando é conhecido mais do que um nome para a mesma localidade selecciona-se o mais recente e/ou com a ortografia mais correcta, sendo os restantes considerados sinónimos. Palavras-chave: Coleoptera; Lepidoptera; Papilionoidea; Localidades de capturas; Coordenadas; Angola. DICIONÁRIO GEOGRÁFICO DAS LOCALIDADES CONHECIDAS DE ANGOLA PARA OS COLEÓPTEROS (COLEOPTERA) E OS LEPIDÓPTEROS DIURNOS (LEPIDOPTERA, PAPILIONOIDEA) Abstract: A list of Angolan localities where beetles (Coleoptera) and butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) were collected is presented. For each site the administrative Province, and the approximate longitude, latitude and altitude, as well as the number of the correspondent 1: 100 000 aero-photogrammetric survey map are reported. When more than one name is known to one only locality, the more recent denomination and/or the correct one is selected and the remaining ones are considered as synonyms. Key words: Coleoptera; Lepidoptera; Papilionoidea; Collecting localities; Coordinates; Angola. (1) Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (IICT). JBT/Zoologia. -

Dotação Orçamental Por Orgão

Exercício : 2013 REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA Emissão : 13/12/2012 MINISTÉRIO DAS FINANÇAS Página : 132 DOTAÇÃO ORÇAMENTAL POR ORGÃO Órgão: Assembleia Nacional RECEITA POR NATUREZA ECONÓMICA Natureza Valor % Total Geral: 120.000.000,00 100,00% Receitas Correntes 120.000.000,00 100,00% Receita De Serviços 120.000.000,00 100,00% Receita De Serviços Diversos 120.000.000,00 100,00% DESPESAS POR NATUREZA ECONÓMICA Natureza Valor % Total Geral: 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% 3 - Despesas Correntes 24.537.739.268,00 80,74% 3.1 - Despesas Com O Pessoal 12.848.012.895,00 42,27% 3.1.1 - Despesas Com O Pessoal Civil 12.848.012.895,00 42,27% 3.2 - Contribuições Do Empregador 282.895.626,00 0,93% 3.2.1 - Contribuições Do Empreg.P/A Segurança Social 282.895.626,00 0,93% 3.3 - Despesas Em Bens E Serviços 11.399.872.347,00 37,51% 3.3.1 - Bens 809.372.089,00 2,66% 3.3.2 - Serviços 10.590.500.258,00 34,85% 3.5 - Subsidios E Transferencias Correntes 6.958.400,00 0,02% 3.5.2 - Transferencias Correntes 6.958.400,00 0,02% 4 - Despesas De Capital 5.853.911.526,00 19,26% 4.1 - Investimentos 5.853.911.526,00 19,26% 4.1.1 - Aquisição De Bens De Capital Fixo 5.598.911.526,00 18,42% 4.1.4 - Compra De Activos Intangíveis 255.000.000,00 0,84% DESPESAS POR FUNÇÃO Função Valor % Total Geral: 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% 1 - Serviços Públicos Gerais 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% 1.0.2.0.0 - Órgãos Executivos 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% DESPESAS POR PROGRAMA Programa Valor % Total Geral: 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% Actividades Permanentes 30.391.650.794,00 100,00% DESPESAS DE FUNCIONAMENTO Projecto -

MINISTRY of PLANNING Public Disclosure Authorized

E1835 REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA v2 MINISTRY OF PLANNING Public Disclosure Authorized EMERGENCY MULTISECTOR RECOVERY PROJECT (EMRP) PROJECT MANAGEMENT IMPLEMENTATION UNIT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Process Report Volume 2 – Environmental and Social Diagnosis and Institutional and Legal Framework INDEX Page 1 - INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................4 2 - THE EMERGENCY ENVIRONMENTAL MULTISECTOR PROJECT (EMRP) ................................................................................................................5 2.1 - EMRP’S OBJECTIVES ..........................................................................................5 2.2 - PHASING................................................................................................................5 2.3 - COMPONENTS OF THE IDA PROJECT .............................................................6 2.3.1 - Component A – Rural Development and Social Services Scheme .............6 2.3.1.1 - Sub-component A1: Agricultural and Rural Development..........6 2.3.1.2 - Sub-Component A2: Health.........................................................8 2.3.1.3 - Sub-Component A3: Education ...................................................9 2.3.2 - Component B – Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of critical Infrastructures ............................................................................................10 2.3.2.1 - Sub-Component -

Angola), 1902‐1961

Neto, Maria da Conceição (2012) In Town and Out of Town: A Social History of Huambo (Angola), 1902‐1961. PhD Thesis, SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/13822 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. In Town and Out of Town: A Social History of Huambo (Angola) 1902-1961 MARIA NETO Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2012 Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2 Abstract This thesis is a history of the Angolan city of Huambo from 1902 to 1961. It is about social change, focusing mainly on people excluded from citizenship by Portuguese colonial laws: the so-called 'natives', whose activities greatly shaped the economic and social life of the city and changed their own lives in the process. Their experiences in coping with and responding to the economic, social and political constraints of the colonial situation were reconstructed from archival documents, newspapers and bibliographical sources, complemented by a few interviews. -

The Changing Face of the Zambia/Angola Border

Draft – not for citation The changing face of the Zambia/Angola border Paper prepared for the ABORNE Conference on ‘How is Africa Transforming Border Studies?’ Hosted by the School of Social Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa 10-14 September 2009 Oliver Bakewell International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, UK [email protected] August 2009 Abstract The establishment of the border between Zambia and Angola by the British and Portuguese at the beginning of the 20th century changed the nature of migration across the upper Zambezi region but did not necessarily diminish it. The introduction of the border was an essential part of the extension of colonial power, but at the same time it created the possibility of crossing the border to escape from one state’s jurisdiction to another: for example, to avoid slavery, forced labour, accusations of witchcraft, taxes and political repression. In the second half the 20th century, war in Angola stimulated the movement of many thousands of refugees into Zambia’s North‐Western Province. The absence of state structures on the Angolan side of the border and limited presence of Zambian authorities enabled people to create an extended frontier reaching deep into Angola, into which people living in Zambia could expand their livelihoods. This paper will explore some of the impacts of the end of the Angolan war in the area and will suggest that the frontier zone is shrinking as the ‘normal’ international border is being reconstructed. Draft – not for citation Draft – not for citation DRAFT – not for citation or circulation Introduction About a century ago, the British and Portuguese finally agreed on the line for the border between the northern portions of their colonies in Zambia and Angola,1 in the area known as the upper Zambezi.