"'68: the Fire Last Time," Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1961 Fleer Football Set Checklist

1961 FLEER FOOTBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Ed Brown ! 2 Rick Casares 3 Willie Galimore 4 Jim Dooley 5 Harlon Hill 6 Stan Jones 7 J.C. Caroline 8 Joe Fortunato 9 Doug Atkins 10 Milt Plum 11 Jim Brown 12 Bobby Mitchell 13 Ray Renfro 14 Gern Nagler 15 Jim Shofner 16 Vince Costello 17 Galen Fiss 18 Walt Michaels 19 Bob Gain 20 Mal Hammack 21 Frank Mestnik RC 22 Bobby Joe Conrad 23 John David Crow 24 Sonny Randle RC 25 Don Gillis 26 Jerry Norton 27 Bill Stacy 28 Leo Sugar 29 Frank Fuller 30 Johnny Unitas 31 Alan Ameche 32 Lenny Moore 33 Raymond Berry 34 Jim Mutscheller 35 Jim Parker 36 Bill Pellington 37 Gino Marchetti 38 Gene Lipscomb 39 Art Donovan 40 Eddie LeBaron 41 Don Meredith RC 42 Don McIlhenny Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 L.G. Dupre 44 Fred Dugan 45 Billy Howton 46 Duane Putnam 47 Gene Cronin 48 Jerry Tubbs 49 Clarence Peaks 50 Ted Dean RC 51 Tommy McDonald 52 Bill Barnes 53 Pete Retzlaff 54 Bobby Walston 55 Chuck Bednarik 56 Maxie Baughan RC 57 Bob Pellegrini 58 Jesse Richardson 59 John Brodie RC 60 J.D. Smith RB 61 Ray Norton RC 62 Monty Stickles RC 63 Bob St.Clair 64 Dave Baker 65 Abe Woodson 66 Matt Hazeltine 67 Leo Nomellini 68 Charley Conerly 69 Kyle Rote 70 Jack Stroud 71 Roosevelt Brown 72 Jim Patton 73 Erich Barnes 74 Sam Huff 75 Andy Robustelli 76 Dick Modzelewski 77 Roosevelt Grier 78 Earl Morrall 79 Jim Ninowski 80 Nick Pietrosante RC 81 Howard Cassady 82 Jim Gibbons 83 Gail Cogdill RC 84 Dick Lane 85 Yale Lary 86 Joe Schmidt 87 Darris McCord 88 Bart Starr 89 Jim Taylor Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan (ET) Tackle: Jim Parker (G) Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas (G) Bo Farrington Leon Clarke (ET) Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Dave Sherer PA Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee (G-ET) Tackle: Dick Schafrath (G) Woodley Lewis Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Bob Fry (G) Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska (G-C) Gene Selawski (G) Paul Dickson Center: Buzz Nutter (LB) Guard: Stan Jones (T) Guard: Jim Ray Smith(T) Byron Bradfute Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras (T) Gene Hickerson Dick Klein (DT) -

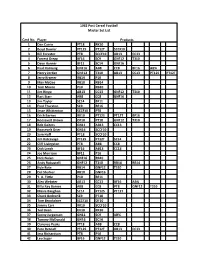

Master Set List

1962 Post Cereal Football Master Set List Card No. Player Products 1 Dan Currie PT18 RK10 2 Boyd Dowler PT12S PT12T SCCF10 3 Bill Forester PT8 SCCF10 AB13 CC13 4 Forrest Gregg BF16 SC9 GNF12 T310 5 Dave Hanner BF11 SC14 GNF16 6 Paul Hornung GNF16 AB8 CC8 BF16 AB¾ 7 Henry Jordan GNF12 T310 AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 8 Jerry Kramer RB14 P10 9 Max McGee RB10 RB14 10 Tom Moore P10 RB10 11 Jim Ringo AB13 CC13 GNF12 T310 12 Bart Starr AB8 CC8 GNF16 13 Jim Taylor SC14 BF11 14 Fred Thurston SC9 BF16 15 Jesse Whittenton SCCF10 PT8 16 Erich Barnes RK10 PT12S PT12T BF16 17 Roosevelt Brown OF10 PT18 GNF12 T310 18 Bob Gaiters GN11 AB13 CC13 19 Roosevelt Grier GN16 SCCF10 20 Sam Huff PT18 SCCF10 21 Jim Katcavage PT12S PT12T SC14 22 Cliff Livingston PT8 AB8 CC8 23 Dick Lynch BF16 AB13 CC13 24 Joe Morrison BF11 P10 25 Dick Nolan GNF16 RB10 26 Andy Robustelli GNF12 T310 RB14 RB14 27 Kyle Rote RB14 GNF12 T310 28 Del Shofner RB10 GNF16 29 Y. A. Tittle P10 BF11 30 Alex Webster AB13 CC13 BF16 AB¾ 31 Billy Ray Barnes AB8 CC8 PT8 GNF12 T310 32 Maxie Baughan SC14 PT12S PT12T 33 Chuck Bednarik SC9 PT18 34 Tom Brookshier SCCF10 OF10 35 Jimmy Carr RK10 SCCF10 36 Ted Dean OF10 RK10 37 Sonny Jurgenson GN11 SC9 AB¾ 38 Tommy McDonald GN16 SC14 39 Clarence Peaks PT18 AB8 CC8 40 Pete Retzlaff PT12S PT12T AB13 CC13 41 Jess Richardson PT8 P10 42 Leo Sugar BF16 GNF12 T310 43 Bobby Walston BF11 GNF16 44 Chuck Weber GNF16 RB10 45 Ed Khayat GNF12 T310 RB14 46 Howard Cassady RB14 BF11 47 Gail Cogdill RB10 BF16 48 Jim Gibbons P10 PT8 49 Bill Glass AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 50 Alex Karras -

Flour Bluff Volunteer Hereabouts in the Past Week

Inside the Moon Spring Break '16 A2 Ukeladies A2 Fishing A11 Live Music A18 Issue 663 The Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 December 29, 2016 Weekly FREE Around The Island by the numbers Island 2016 The Year Nueces County Emergency Services By Dale Rankin As we wind down to the end of 2016 District #2 on our little sandbar we are hunkered down for the last blue northern of the That Was $6919 cost per call for 2015, year to blow through as the Weather As we look back on 2016 here are some of the Wonks tell us to expect winds of 45 $8470 per call estimated for 2016 knots and offshore seas of nine to highlights that we saw on our Island. eleven feet. The Nueces County Emergency $1.2 million Net Assets of Lake Padre Work Services District #2 (Originally according to a 2015 audit Here is some of what has happened called the Flour Bluff Volunteer hereabouts in the past week. $837,335 raised from property Fire Department) is located at tax in 2015 New beach signs 337 Yorktown Road in Flour Bluff. They provide fire, water New signs are going up along our and auto rescue and EMS 2016-2017 beaches this week. The first of the services to an 80 square-mile new signs was at the parking lot at area which includes Flour Proposed Budget Michael J. Ellis Beach. Bluff, Padre Island, Padre Island National Seashore, and $1,177,330 total income unincorporated areas of Kleberg $8470 per service call in 2016- and Nueces County. -

APBA 1959 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1959 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1959 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1959 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 9-3 CHICAGO (W) 8-4 CHICAGO ( E) 2-10 CLEVELAND 7-5 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Harlon Hill Wide Receiver: Woodley Lewis Wide Receiver: Preston Carpenter Jim Mutscheller (DE) Willard Dewveall John Tracey Billy Howton Jerry Richardson Bill McColl Perry Richards TC Tackle: Lou Groza KA KOA Dave Sherer PA Lionel Taylor Sonny Randle OC Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Jim Parker Tackle: Herman Lee Tackle: Dale Memmelaar Fran O'Brien George Preas (LB) Dick Klein Ken Panfil OC Guard: Jim Ray Smith Sherman Plunkett OC Ed Nickla Bobby Cross (DT) OC Gene Hickerson Guard: Art Spinney Guard: Abe Gibron Mac Lewis Dick Schafrath Alex Sandusky Stan Jones Ed Cook (DT) KB KOB John Wooten Steve Myhra (2) OC KA KOA Center: John Mellekas Guard: Dale Meinert (MLB) Center: Art Hunter Center: Buzz Nutter John Damore Ken Gray (LB) OC Quarterback: Milt Plum KB Quarterback: Johnny Unitas MVP Larry Strickland Center: Don Gillis Jim Ninowski Halfback: Mike Sommer OB Quarterback: Ed Brown PA Quarterback: King Hill PB Bob Ptacek (HB) Lenny Moore Zeke Bratkowski M.C. -

Jimmy Orr Gino Marchetti Johnny Morris TA Doug Atkins Raymond

1963 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1963 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. BALTIMORE BALTIMORE CHICAG0 CHICAG0 OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Jimmy Orr End: Gino Marchetti EB: Johnny Morris TA End: Doug Atkins Raymond Berry Ordell Braase Bo Farrington Bob Kilcullen Willie Richardson TC OC Don Thompson Angelo Coia Ed O'Bradovich R.C. Owens Tackle: Jim Colvin Tackle: Bob Wetoska Tackle: Stan Jones Tackle: George Preas Fred Miller Herman Lee Earl Leggett Bob Vogel John Diehl Steve Barnett John Johnson OC Guard: Alex Sandusky LB: Jackie Burkett Guard: Roger Davis Fred Williams Jim Parker OC Bill Pellington Ted Karras LB: Joe Fortunato Dan Sullivan Don Shinnick Jim Cadile Bill George Palmer Pyle Bill Saul Center: Mike Pyle OC Larry Morris Center: Dick Szymanski Butch Maples ET: Mike Ditka Tom Bettis ET: John Mackey OB CB: Bobby Boyd Bob Jencks KA KOB PB Roger LeClerc (2) KA KOA Butch Wilson Lenny Lyles QB: Billy Wade CB: Bennie McRae QB: Johnny Unitas Safety: Andy Nelson Rudy Bukich Dave Whitsell (2) Gary Cuozzo Jim Welch HB: Willie Galimore OC J.C. -

APBA 1957 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1957 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1957 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1957 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Balimore Chicago (W) Chicago ( E) Cleveland Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Harlon Hill Wide Receiver: Woodley Lewis TA OA Wide Receiver: Pete Brewster Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Gern Nagler Preston Carpenter Tackle: Jim Parker Gene Schroeder Max Boydston Frank Clarke OC George Preas Tackle: Bill Wightkin Tackle: Len Teeuws Tackle: Lou Groza KA KOA Ken Jackson Kline Gilbert Jack Jennings Mike McCormack Guard: Art Spinney Guard: Herman Clark Dave Lunceford Guard: Herschel Forester Alex Sandusky Stan Jones Guard: Doug Hogland Fred Robinson TC Steve Myhra OC KOA KB Tom Roggeman Bob Konovsky Jim Ray Smith Center: Buzz Nutter Center: Larry Strickland Charlie Toogood Center: Art Hunter Dick Szymanski John Damore OC Center: Earl Putman Joe Amstutz Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Quarterback: Ed Brown PB Jim Taylor Quarterback: Tommy O'Connell George Shaw George Blanda KA KOA Quarterback: Lamar McHan PB Milt Plum Cotton Davidson OC PA Zeke Bratkowski PB Ted Marchibroda John Borton Halfback: L.G. -

Fred Miller, Pro Bowl Defensive Tackle

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 25, No. 4 (2003) Fred Miller, Defensive Tackle From the “Iron Men” of Homer, Louisiana, to the Super Bowl By Jim Sargent When Fred Miller began his final high school season in Homer, Louisiana, in 1957, he shared the same unspoken dreams of most of his teammates. He and his football buddies hoped Homer High would have a good year. Most of his teammates also hoped they could play college football and earn degrees. By the time Miller took off his pads for the last time after the 1972 season, football had provided him with a good life. Fred had anchored the line on Homer’s championship team, received All-American honors on two Louisiana State University bowl-winning squads, won Pro Bowl recognition three times with the Baltimore Colts in the National Football League, and earned a Super Bowl Ring in 1971. In other words, Miller had the ability and the good fortune of playing on outstanding teams at the high school, college, and pro levels. He still has good friends who played alongside him on all three teams. Fed says the camaraderie and the fleeting glory he experienced on those gridirons of three or four decades ago made all of the up-and-downs worthwhile. Born on August 8, 1940, Fred grew up in Homer, a small town in the oil field region of northern Louisiana. Most people in the area loved high school football. The Homer oil field became a boom area in the 1940s after H.L. Hunt drilled his first well within 20 miles. -

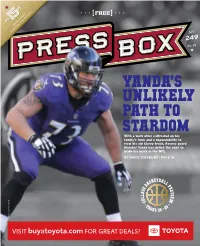

OPINION Parallels Can Be Drawn Between Ravens Head

families sports PA GE for winter activities 249 11.18 Yanda’s Unlikely Path To Stardom With a work ethic cultivated on his family’s farm and a dependability to rival his old Chevy truck, Ravens guard Marshal Yanda has defied the odds to make his mark in the NFL BY DAVID GINSBURG | PAGE 16 TB SKE ALL A P B R E E G V E I L E W L O C PA 9 GEs 26 - 2 KENYA ALLEN/PRESSBOX KENYA VISIT b uy a toyot a . c o m FOR GREAT DEALS! Issue 249 • 11.15.18 Epic - table of contents - Events COVER STORY at Yanda’s Unlikely Path To Stardom.......................... 16 INOURNEW SEATEVENTCENTER With a work ethic cultivated on his family’s farm and a depend- ability to rival his old Chevy truck, Ravens guard Marshal Yanda has defied the odds to make his mark in the NFL welcome to By David Ginsburg FEATURE STORIES Ravens Report w/ Bo Smolka.................................... 13 Orioles Report w/ Todd Karpovich .........................20 SOLD OUT Varsity Report w/ Jeff Seidel................................... 32 Sports Business w/ Baltimore Business Journal...... 34 SPECIAL SECTION CHRISD’ELIA College Basketball Preview.................................... 26 PATTILABELLE FOLLOWTHELEADERTOUR DECEMBER MARCH SPECIAL FEATURE Book Excerpt ...........................................................09 COLUMNS > One Fan’s Opinion .................................................05 Stan “The Fan” Charles > Upon Further Review ............................................21 JAGGEDEDGE& Jim Henneman FEATMIKE&SLIM THEXPERIENCETOUR > The Reality Check ................................................37 -

1961 Post Cereal Company Uncut Team Sheets

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #169 1961 POST CEREAL COMPANY UNCUT TEAM SHEETS For the first time in our nearly 50 years of business we have acquired a complete run of these amazing Post Cereal company uncut team sheets. Only available through a mail-in offer from Post. Sheets were issued in a perforated format and contain 10 players each. Extremely rare – call for your team or teams. Each sheet measures approximately 7” x 12-1/2” and are in solid EX-MT/NR-MT condition. Baltimore Orioles inc. B. Boston Red Sox inc. Tasby, Chicago Cubs inc. Banks, Chicago White Sox inc. Fox, Cincinnati Reds inc. F. Robinson, Wilhelm, Gentile, Runnels, Malzone, etc. Santo, Ashburn, etc. Aparicio, Minoso, Wynn, Robinson, Pinson, Billy etc. $595.00 $595.00 $695.00 etc. $495.00 Martin, etc. $650.00 Cleveland Indians inc. Kansas City A’s inc. Bauer, Los Angeles Dodgers inc. Milwaukee Braves inc. Minnesota Twins inc. Perry, Francona, Power, etc. Throneberry, Herzog, etc. Drysdale, Snider, Hodges, Aaron, Mathews, Spahn, Killebrew, Stobbs, Allison, $495.00 $495.00 Wills, etc. $995.00 Adcock, etc. $995.00 etc. $650.00 New York Yankees inc. Philadelphia Phillies inc. Pittsburgh Pirates inc. San Francisco Giants inc. St. Louis Cardinals inc. Mantle, Berra, Maris, Ford, Callison, Taylor, Robin Clemente, Mazeroski, Groat, Mays, McCovey, Cepeda, Boyer, White, Flood, etc. etc. $1995.00 Roberts, etc.$495.00 Law, etc. $995.00 etc. $895.00 $595.00 KIT YOUNG CARDS . 4876 SANTA MONICA AVE, #137. DEPT. 169. SAN DIEGO,CA 92107. (888) 548-9686. KITYOUNG.COM Page 2 GOODIES FROM THE ROAD Nacho and I have just returned from our longest buying trip ever. -

Championship Game, They Have the Home Field and They've Earned It

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS HEAD COACH BILL BELICHICK PRESS CONFERENCE January 18, 2007 BB: We're plugging along here, just watching the Colts on third down. They're pretty impressive really. Nobody does it better than they do. Offensively, they set the standard during the regular season this year, and of course in the playoffs, defensively, they've shut two teams down to almost nothing. I’m sure that will be a big factor in the game, as it always is a very important part of the game. We'll try to put a little extra work in on that and hope we can be competitive in that area. Q: When you look at [Tedy] Bruschi and Troy Brown's careers here, do you see a similarity in terms of what they've done here and how they've risen up as Patriots and what they've been to this franchise? BB: Sure. They probably would have a lot more in common as a comparison than some other guys that you could name. Yes. Tough, hard-working guys that set a great example. They're great players. They set a great example for everybody else. They put the team first. They're good to coach. They're good to work with. I'm glad we have them. Q: I would assume a big part of your preparation is to try to be third-and-manageable when you're working on third down. What is third-and-manageable? BB: No question we’re trying to do that. That's an objective for us every week. -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan Tackle: Jim Parker Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas Bo Farrington Leon Clarke Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Woodley Lewis Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee Tackle: Dick Schafrath Tackle: Bob Fry Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack Paul Dickson Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska Gene Selawski Byron Bradfute Center: Buzz Nutter Guard: Stan Jones Guard: Jim Ray Smith Dick Klein Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras Gene Hickerson Guard: Duane Putnam OC Ray Brown PA Roger Davis John Wooten Buzz Guy Halfback: Alex