The President's Corner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America's Charity Fundraising

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: California Autographed Sports Memorabilia Inventory Updated 10/04/2013 California Angels 1. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $380.00 2. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $175.00 3. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001-02) $201.00 4. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $305.00 5. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001- 02) $150.00 6. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001-02) $175.00 LA Dodgers 1. Dusty Baker Los Angeles Dodgers Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $285.00 2. Autographed Pedro Guerrero Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $265.00 3. Autographed Pedro Guerrero MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $150.00 4. Autographed Orel Hershiser Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $325.00 5. Autographed Orel Hershiser Baseball Inscribed 88 WS MVP and 88 WS Cy Young (BWU001-02) $190.00 6. -

My Emlen Tunnell Story by David Lyons

My Emlen Tunnell Story By David Lyons I grew up listening to stories told by my father, Bill Lyons, about his friend Emlen Tunnell, and we were both always amazed that a biography was never written about him. After considerable reflection and a push from my dad, I decided that I would take that journey and write about our local legend’s life, so that more people would know about his remarkable life story. The American public knows plenty about sports heroes like Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron, but few remember or have even heard of Emlen Tunnell. He is a forgotten star who pioneered his way into the NFL in an uncharacteristic way at the time; he went to the New York Giants office and asked for a tryout. Dozens of books have been written about Jackie Robinson and Vince Lombardi, but none have ever been written about the great Emlen “the Gremlin” Tunnell, who most friends called “Em.” Emlen Tunnell wasn’t merely a legendary football player, he was a highly charismatic real person who was kind to his family and friends. He became a part of my childhood because my dad would share delightful stories around our dinner table with me and my six brothers. Dad was a neighbor and friend of Emlen’s. One of the stories Dad shared with us was how Emlen was moved to tears when a group of homeless guys took up a collection for him when the New York Giants held an Emlen Tunnell Day in 1958. The money collected was less than $30, but Emlen said, “These guys probably gave me all the money they had, and who can ever be more generous than that?” Emlen was a very sensitive and sentimental guy who wore his heart on his sleeve and would tear up rather easily when he felt moved. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

UD FB Media Guide.Indd

THE UNIVERSITY Rounded ..................................................................1850 Enrollment ......................................................... 8,000 Colors Red (PMS 199C) & Blue (PMS 655C) Conference ................Pioneer Football League President ...............................Dr. Daniel J. Curran VP/Director of Athletics .................Tim Wabler Stadium ....................................Welcome Stadium Capacity ...............................................................11,000 Surface ...............................................257 Sport Turf INTRODUCTION Laulien, Macis, Madden .................35 Press Box ......................................(937) 542-4093 Ticket Offi ce ...............................(937) 229-4433 Flyer Football Tradition ....................4 McManamon, Middleton, Morgan 36 The NFL Connection .......................5-6 Morgan, Nees, Ney .............................37 ATHLETICS COMMUNICATION The Outlook .......................................... 7-8 Nuzzolese, Osborne, Palin .............38 Football Contact .......................Doug Hauschild Email [email protected] Team Roster ............................................10 Pignatiello, Powers, Ryan ..............39 Offi ce ...............................................(937) 229-4390 Depth Chart/Roster ............................12 Sanders, Schwenke, Scott .............40 Cell .....................................................(937) 272-4503 Fax .....................................................(937) -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Clean Sweep All Sports Affordable Autograph/Memorabilia Auction Day One Wednesday December 11 Lots 1 - 804 Baseball Autographs ..................................................................................................................................... 6-43 Signed Cards ................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 Signed Photos.................................................................................................................................. 11-13, 24-31 Signed Cachets ............................................................................................................................................ 13-15 Signed Documents ..................................................................................................................................... 15-17 Signed 3x5s & Related ................................................................................................................................ 18-21 Signed Yearbooks & Programs ................................................................................................................. 21-23 Single Signed Baseballs ............................................................................................................................ -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

College All-Star Football Classic, August 2, 1963 • All-Stars 20, Green Bay 17

College All-Star Football Classic, August 2, 1963 • All-Stars 20, Green Bay 17 This moment in pro football history has always captured my imagination. It was the last time the college underdogs ever defeated the pro champs in the long and storied history of the College All-Star Football Classic, previously known as the Chicago Charities College All-Star Game, a series which came to an abrupt end in 1976. As a kid, I remember eagerly awaiting this game, as it signaled the beginning of another pro football season—which somewhat offset the bittersweet knowledge that another summer vacation was quickly coming to an end. Alas, as the era of “big money” pro sports set in, the college all star game quietly became a quaint relic of a more innocent sporting past. Little by little, both the college stars and the teams which had shelled out guaranteed contracts to them began to have second thoughts about participation in an exhibition game in which an injury could slow or even terminate a player’s career development. The 1976 game was played in a torrential downpour, halted in the third quarter with Pittsburgh leading 24-0, and the game—and, indeed, the series—was never resumed. But on that sultry August evening in 1963, with a crowd of 65,000 packing the stands, the idea of athletes putting financial considerations ahead of “the game” wasn’t on anyone’s minds. Those who were in the stands or watching on televiosn were treated to one of the more memorable upsets in football history, as the “college Joes” knocked off the “football pros,” 20-17. -

1961 Fleer Football Set Checklist

1961 FLEER FOOTBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Ed Brown ! 2 Rick Casares 3 Willie Galimore 4 Jim Dooley 5 Harlon Hill 6 Stan Jones 7 J.C. Caroline 8 Joe Fortunato 9 Doug Atkins 10 Milt Plum 11 Jim Brown 12 Bobby Mitchell 13 Ray Renfro 14 Gern Nagler 15 Jim Shofner 16 Vince Costello 17 Galen Fiss 18 Walt Michaels 19 Bob Gain 20 Mal Hammack 21 Frank Mestnik RC 22 Bobby Joe Conrad 23 John David Crow 24 Sonny Randle RC 25 Don Gillis 26 Jerry Norton 27 Bill Stacy 28 Leo Sugar 29 Frank Fuller 30 Johnny Unitas 31 Alan Ameche 32 Lenny Moore 33 Raymond Berry 34 Jim Mutscheller 35 Jim Parker 36 Bill Pellington 37 Gino Marchetti 38 Gene Lipscomb 39 Art Donovan 40 Eddie LeBaron 41 Don Meredith RC 42 Don McIlhenny Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 L.G. Dupre 44 Fred Dugan 45 Billy Howton 46 Duane Putnam 47 Gene Cronin 48 Jerry Tubbs 49 Clarence Peaks 50 Ted Dean RC 51 Tommy McDonald 52 Bill Barnes 53 Pete Retzlaff 54 Bobby Walston 55 Chuck Bednarik 56 Maxie Baughan RC 57 Bob Pellegrini 58 Jesse Richardson 59 John Brodie RC 60 J.D. Smith RB 61 Ray Norton RC 62 Monty Stickles RC 63 Bob St.Clair 64 Dave Baker 65 Abe Woodson 66 Matt Hazeltine 67 Leo Nomellini 68 Charley Conerly 69 Kyle Rote 70 Jack Stroud 71 Roosevelt Brown 72 Jim Patton 73 Erich Barnes 74 Sam Huff 75 Andy Robustelli 76 Dick Modzelewski 77 Roosevelt Grier 78 Earl Morrall 79 Jim Ninowski 80 Nick Pietrosante RC 81 Howard Cassady 82 Jim Gibbons 83 Gail Cogdill RC 84 Dick Lane 85 Yale Lary 86 Joe Schmidt 87 Darris McCord 88 Bart Starr 89 Jim Taylor Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan (ET) Tackle: Jim Parker (G) Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas (G) Bo Farrington Leon Clarke (ET) Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Dave Sherer PA Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee (G-ET) Tackle: Dick Schafrath (G) Woodley Lewis Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Bob Fry (G) Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska (G-C) Gene Selawski (G) Paul Dickson Center: Buzz Nutter (LB) Guard: Stan Jones (T) Guard: Jim Ray Smith(T) Byron Bradfute Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras (T) Gene Hickerson Dick Klein (DT) -

THE FORDHAM RAM Lol

I Giant-Fordham Football Rally At 11 A.M. In Gym THE FORDHAM RAM lol. 46, No. 16 Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y. 10458, October 9, 1964 401 Twelve Page* lialogue Lecturer Gives Gould Gets Post With ASGUSA O'Doherty to Speak; iews On Birth Control P.R. Committee Keating Reschedules Rev. George Hagmaier, C.S.P., speaking on "Marriage John Gould, a College junior, As the large division loblcm's and Agglonmmento," Wednesday night told a-Cam- has been named chairman of a political loyalties among Ford- is Center audience that Catholic parents "are not obliged committee to study public rela- tions for the Associated Student ham students is being record- I have as many children as God may send, but must take into Governments, United States of ed in this week's RAM straw 'nsidcration the economic, social, and psychological factors" America. Gould -was among tm-ee poll, Senatorial and Congres- which a child would he raised. Foidham men who attended the sional hopefuls of all parties ,'A moral responsibility," Fa-'* ' ASGUSA charter meeting last are planning to bring their jor Hagmaier continued, "is ex- April. battles to the Fordham cam- Iciscd in the sexual act, the At that time, student govern- pus. eminent of love," which, is the ment leaders from 62 colleges The American Age Lecture tal giving of one's total self. met in St. Louis to consider Series announced that Sen. Ken- a'viiagc : is ' not contained in the formation of a new "non- neth Keating and Robert F. Ken- ly this act, however, but is political" union of college gov- nedy, Republican and Democratic interaction of many eino- ernments in the U.S. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

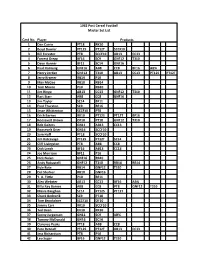

Master Set List

1962 Post Cereal Football Master Set List Card No. Player Products 1 Dan Currie PT18 RK10 2 Boyd Dowler PT12S PT12T SCCF10 3 Bill Forester PT8 SCCF10 AB13 CC13 4 Forrest Gregg BF16 SC9 GNF12 T310 5 Dave Hanner BF11 SC14 GNF16 6 Paul Hornung GNF16 AB8 CC8 BF16 AB¾ 7 Henry Jordan GNF12 T310 AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 8 Jerry Kramer RB14 P10 9 Max McGee RB10 RB14 10 Tom Moore P10 RB10 11 Jim Ringo AB13 CC13 GNF12 T310 12 Bart Starr AB8 CC8 GNF16 13 Jim Taylor SC14 BF11 14 Fred Thurston SC9 BF16 15 Jesse Whittenton SCCF10 PT8 16 Erich Barnes RK10 PT12S PT12T BF16 17 Roosevelt Brown OF10 PT18 GNF12 T310 18 Bob Gaiters GN11 AB13 CC13 19 Roosevelt Grier GN16 SCCF10 20 Sam Huff PT18 SCCF10 21 Jim Katcavage PT12S PT12T SC14 22 Cliff Livingston PT8 AB8 CC8 23 Dick Lynch BF16 AB13 CC13 24 Joe Morrison BF11 P10 25 Dick Nolan GNF16 RB10 26 Andy Robustelli GNF12 T310 RB14 RB14 27 Kyle Rote RB14 GNF12 T310 28 Del Shofner RB10 GNF16 29 Y. A. Tittle P10 BF11 30 Alex Webster AB13 CC13 BF16 AB¾ 31 Billy Ray Barnes AB8 CC8 PT8 GNF12 T310 32 Maxie Baughan SC14 PT12S PT12T 33 Chuck Bednarik SC9 PT18 34 Tom Brookshier SCCF10 OF10 35 Jimmy Carr RK10 SCCF10 36 Ted Dean OF10 RK10 37 Sonny Jurgenson GN11 SC9 AB¾ 38 Tommy McDonald GN16 SC14 39 Clarence Peaks PT18 AB8 CC8 40 Pete Retzlaff PT12S PT12T AB13 CC13 41 Jess Richardson PT8 P10 42 Leo Sugar BF16 GNF12 T310 43 Bobby Walston BF11 GNF16 44 Chuck Weber GNF16 RB10 45 Ed Khayat GNF12 T310 RB14 46 Howard Cassady RB14 BF11 47 Gail Cogdill RB10 BF16 48 Jim Gibbons P10 PT8 49 Bill Glass AB13 CC13 PT12S PT12T 50 Alex Karras