Journal of Stevenson Studies Volume 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: a Survey and Analysis

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: A Survey and Analysis STEPHEN E. TABACHNICK University of Memphis OWING TO A LARGE NUMBER of excellent adaptations, it is now possible to read and to teach a good deal ot the Transition period litera- ture with the aid of graphic, or comic book, novels. The graphic novei is an extended comic book, written by adults for adults, which treats important content in a serious artistic way and makes use of high- quality paper and production techniques not available to the creators of the Sunday comics and traditional comic books. This flourishing new genre can be traced to Belgian artist Frans Masereel's wordless wood- cut novel. Passionate Journey (1919), but the form really took off in the 1960s and 1970s when creators in a number of countries began to employ both words and pictures. Despite the fictional implication of graphic "novel," the genre does not limit itself to fiction and includes numerous works of autobiography, biography, travel, history, reportage and even poetry, including a brilliant parody of T. S. Eliot's Waste Land by Martin Rowson (New York: Harper and Row, 1990) which perfectly captures the spirit of the original. However, most of the adaptations of 1880-1920 British literature that have been published to date (and of which I am aware) have been limited to fiction, and because of space considerations, only some of them can be examined bere. In addition to works now in print, I will include a few out-of-print graphic novel adap- tations of 1880-1920 literature hecause they are particularly interest- ing and hopefully may return to print one day, since graphic novels, like traditional comics, go in and out of print with alarming frequency. -

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Robert Louis Stevenson By

iriLOUISiSTEVENSON ! BY J^ MARGARET OYES BIACK FAMOUS •SCOT5« •SERIES' THIS BOOK IS FROM THE LIBRARY OF Rev. James Leach ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ': J ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON BY : MARGARET MOVES BLACK ^"^'famous (^^ •SCOTS- •SERIES' PUBLISHED BY W OUPHANT ANDERSON IfFERRIEREDINBVRGH AND LONDON ^ '^;^ 3) n/^'^^' The designs and ornaments of this volume are by Mr Joseph Brown, and the printing from the press of Messrs TurnbuU & Spears, Edinburgh. PREFACE AND DEDICATION In so small a volume it would be somewhat hopeless to attempt an exhaustive notice of R. L. Stevenson, nor would it be desirable. The only possible full biography of him will be the Life in preparation by his intimate friend Mr Sidney Colvin, and for it his friends and his public look eagerly. This little book is only a remini- scence and an appreciation by one who, in the old days between 1869 and 1880, knew him and his home circle well. My earlier and later knowledge has been derived from his mother and those other members of his mother's family with whom it was a pleasure to talk of him, and to exchange news of his sayings and doings. In the actual writing of this volume, I have received most kind help for which I return grateful thanks to the givers. For the verification of dates and a few other particulars I am indebted to Mr Colvin's able article in the Dictionary of National Biography. It is dedicated, in the first instance, to the memory 6 PREFACE AND DEDICATION of Mr and Mrs Thomas Stevenson and their son, and, in the second, to all the dearly prized friends of the Balfour connection who have either, like the household at 1 7 Heriot Row, passed into the ' Silent Land,' or who are still here to gladden life with their friendship. -

Journal of Stevenson Studies

1 Journal of Stevenson Studies 2 3 Editors Dr Linda Dryden Professor Roderick Watson Reader in Cultural Studies English Studies Faculty of Art & Social Sciences University of Stirling Craighouse Stirling Napier University FK9 4La Edinburgh Scotland Scotland EH10 5LG Scotland Tel: 0131 455 6128 Tel: 01786 467500 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Contributions to future issues are warmly invited and should be sent to either of the editors listed above. The text should be submitted in MS WORD files in MHRA format. All contributions are subject to review by members of the Editorial Board. Published by The Centre for Scottish Studies University of Stirling © the contributors 2005 ISSN: 1744-3857 Printed and bound in the UK by Antony Rowe Ltd. Chippenham, Wiltshire. 4 Journal of Stevenson Studies Editorial Board Professor Richard Ambrosini Professor Gordon Hirsch Universita’ de Roma Tre Department of English Rome University of Minnesota Professor Stephen Arata Professor Katherine Linehan School of English Department of English University of Virginia Oberlin College, Ohio Professor Oliver Buckton Professor Barry Menikoff School of English Department of English Florida Atlantic University University of Hawaii at Manoa Dr Jenni Calder Professor Glenda Norquay National Museum of Scotland Department of English and Cultural History Professor Richard Dury Liverpool John Moores University of Bergamo University (Consultant Editor) Professor Marshall Walker Department of English The University of Waikato, NZ 5 Contents Editorial -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of J.M. Barrie, S.R. Crocket

——; — ! 92 STEVENSONIANA VIII ISLAND DAYS TO TUSITALA IN VAILIMA^ Clearest voice in Britain's chorus, Tusitala Years ago, years four-and-twenty. Grey the cloudland drifted o'er us, When these ears first heard you talking, When these eyes first saw you smiling. Years of famine, years of plenty, Years of beckoning and beguiling. Years of yielding, shifting, baulking, ' When the good ship Clansman ' bore us Round the spits of Tobermory, Glens of Voulin like a vision. Crags of Knoidart, huge and hoary, We had laughed in light derision. Had they told us, told the daring Tusitala, What the years' pale hands were bearing, Years in stately dim division. II Now the skies are pure above you, Tusitala; Feather'd trees bow down to love you 1 This poem, addressed to Robert Louis Stevenson, reached him at Vailima three days before his death. It was the last piece of verse read by Stevenson, and it is the subject of the last letter he wrote on the last day of his life. The poem was read by Mr. Lloyd Osbourne at the funeral. It is here printed, by kind permission of the author, from Mr. Edmund Gosse's ' In Russet and Silver,' 1894, of which it was the dedication. After the Photo by] [./. Davis, Apia, Samoa STEVENSON AT VAILIMA [To face page i>'l ! ——— ! ISLAND DAYS 93 Perfum'd winds from shining waters Stir the sanguine-leav'd hibiscus That your kingdom's dusk-ey'd daughters Weave about their shining tresses ; Dew-fed guavas drop their viscous Honey at the sun's caresses, Where eternal summer blesses Your ethereal musky highlands ; Ah ! but does your heart remember, Tusitala, Westward in our Scotch September, Blue against the pale sun's ember, That low rim of faint long islands. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson by Robert Louis

Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson By Robert Louis Stevenson 1 PREFACE The text of the following essays is taken from the Thistle Edition of Stevenson's Works, published by Charles Scribner's Sons, in New York. I have refrained from selecting any of Stevenson's formal essays in literary criticism, and have chosen only those that, while ranking among his masterpieces in style, reveal his personality, character, opinions, philosophy, and faith. In the Introduction, I have endeavoured to be as brief as possible, merely giving a sketch of his life, and indicating some of the more notable sides of his literary achievement; pointing out also the literary school to which these Essays belong. A lengthy critical Introduction to a book of this kind would be an impertinence to the general reader, and a nuisance to a teacher. In the Notes, I have aimed at simple explanation and some extended literary comment. It is hoped that the general recognition of Stevenson as an English classic may make this volume useful in school and college courses, while it is not too much like a textbook to repel the average reader. I am indebted to Professor Catterall of Cornell and to Professor Cross of Yale, and to my brother the Rev. Dryden W. Phelps, for some assistance in locating references. W.L.P., YALE UNIVERSITY, 13 February 1906. 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BIBLIOGRAPHY I ON THE ENJOYMENT OF UNPLEASANT PLACES NOTES II AN APOLOGY FOR IDLERS NOTES III AES TRIPLEX NOTES IV TALK AND TALKERS NOTES V A GOSSIP ON ROMANCE NOTES VI THE CHARACTER OF DOGS NOTES VII A COLLEGE MAGAZINE NOTES 3 VIII BOOKS WHICH HAVE INFLUENCED ME NOTES IX PULVIS ET UMBRA NOTES 4 INTRODUCTION I LIFE OF STEVENSON Robert Louis Stevenson[1] was born at Edinburgh on the 13 November 1850. -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of JM Barrie, SR Crocket

: R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES 225 XII R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES Few authors of note have seen so many and frank judg- ments of their work from the pens of their contemporaries as Stevenson saw. He was a ^persona grata ' with the whole world of letters, and some of his m,ost admiring critics were they of his own craft—poets, novelists, essayists. In the following pages the object in view has been to garner a sheaf of memories and criticisms written—before and after his death—for the most part by eminent contemporaries of the novelist, and interesting, apart from intrinsic worth, by reason of their writers. Mr. Henry James, in his ' Partial Portraits,' devotes a long and brilliant essay to Stevenson. Although written seven years prior to Stevenson's death, and thus before some of the most remarkable productions of his genius had appeared, there is but little in -i^^^ Mr. James's paper which would require modi- fication to-day. Himself the wielder of a literary style more elusive, more tricksy than Stevenson's, it is difficult to take single passages from his paper, the whole galaxy of thought and suggestion being so cleverly meshed about by the dainty frippery of his manner. Mr. James begins by regretting the 'extinction of the pleasant fashion of the literary portrait,' and while deciding that no individual can bring it back, he goes on to say It is sufficient to note, in passing, that if Mr. Stevenson had P 226 STEVENSONIANA presented himself in an age, or in a country, of portraiture, the painters would certainly each have had a turn at him. -

International Edition ACMRS PRESS 219

Spring 2021 CHICAGO International Edition ACMRS PRESS 219 ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY PRESSES 283 AUTUMN HOUSE PRESS 194 BARD GRADUATE CENTER 165 BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY PRESS 168 CAMPUS VERLAG 256 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY PRESS 185 CAVANKERRY PRESS 190 CSLI PUBLICATIONS 281 CONTENTS DIAPHANES 244 EPFL PRESS 275 General Interest 1 GALLAUDET UNIVERSITY PRESS 284 Academic Trade 19 GINGKO LIBRARY 202 Trade Paperbacks 29 HAU 237 Special Interest 39 ITER PRESS 263 Paperbacks 106 KAROLINUM PRESS, CHARLES UNIVERSITY PRAGUE 206 Distributed Books 118 KOÇ UNIVERSITY PRESS 240 Author Index 288 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN WARSAW 160 Title Index 290 NEW ISSUES POETRY AND PROSE 183 Guide to Subjects 292 OMNIDAWN PUBLISHING, INC. 177 Ordering Information Inside back cover PRICKLY PARADIGM PRESS 236 RENAISSANCE SOCIETY 163 SEAGULL BOOKS 118 SMART MUSEUM OF ART, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO 161 TENOV BOOKS 164 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA PRESS 213 UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1 UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI PRESS 199 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS The Subversive Simone Weil A Life in Five Ideas Robert Zaretsky Distinguished literary biographer Robert Zaretsky upends our thinking on Simone Weil, bringing us a woman and a philosopher who is complicated and challenging, while remaining incredibly relevant. Known as the “patron saint of all outsiders,” Simone Weil (1909–43) was one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable thinkers, a philos- opher who truly lived by her political and ethical ideals. In a short life MARCH framed by the two world wars, Weil taught philosophy to lycée students 200 p. 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 and organized union workers, fought alongside anarchists during the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54933-0 Spanish Civil War and labored alongside workers on assembly lines, Cloth $20.00/£16.00 joined the Free French movement in London and died in despair BIOGRAPHY PHILOSOPHY because she was not sent to France to help the Resistance. -

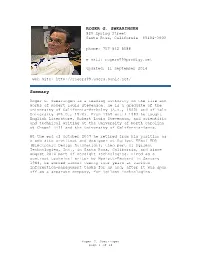

ROGER G. SWEARINGEN Summary

ROGER G. SWEARINGEN 829 Spring Street Santa Rosa, California 95404-3903 phone: 707 542-5088 e-mail: [email protected] updated: 11 September 2014 web site: http://rogers99.users.sonic.net/ Summary Roger G. Swearingen is a leading authority on the life and works of Robert Louis Stevenson. He is a graduate of the University of California-Berkeley (A.B., 1965) and of Yale University (Ph.D., 1970). From 1969 until 1983 he taught English Literature, Robert Louis Stevenson, and scientific and technical writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of California-Davis. At the end of October 2007 he retired from his position as a web site architect and designer at Agilent EEsof EDA (Electronic Design Automation), then part of Agilent Technologies, Inc., in Santa Rosa, California, and since August 2014 part of Keysight Technologies. Hired as a contract technical writer by Hewlett-Packard in January 1984, he worked almost twenty-four years at various information-management tasks for HP and, after it was spun off as a separate company, for Agilent Technologies. Roger G. Swearingen page 1 of 12 Publications Books The Hair Trunk or The Ideal Commonwealth: An Extravaganza . Edited with an introduction and notes from the manuscript in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Kilkerran, Scotland: Humming Earth / Zeticula, 2014. Robert Louis Stevenson in Australia: Treasures in the State Library of New South Wales . Commentaries created in support of an exhibition of Stevenson items by the State Library of New South Wales coordinated with 'RLS 2013: Stevenson, Time and History', the Seventh Biennial Robert Louis Stevenson Conference, hosted by the University of New South Wales, Sydney, 8 - 10 July 2013. -

Top Things to Do in Apia" This Quaint Capital of Samoa Is Known for Its Old Capital Mulinu'u and the Primary City Cathedral

"Top Things To Do in Apia" This quaint capital of Samoa is known for its old capital Mulinu'u and the primary city cathedral. But primarily, its the azure waters, the golden sand beaches and the green cityscape that brings in visitors year in, year out. 创建: Cityseeker 10 位置已标记 Mount Vaea山 "Samoa's Natural Landmark" One of Samoa’s most famous sights is the emerald green peak of Mount Vaea, where the famed writer Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife Fanny are buried. Buried here in 1894, the renowned writer spent the last four years of his life enjoying Samoa’s natural splendor. The trail up to Stevenson’s grave, which sits in the by Teinesavaii shadow of Mount Vaea’s peak, is known as the “Road of Loving Hearts.” Visitors to the burial site will have roughly an hour long walk ahead of them, their eyes treated to beautiful vistas along the way. The surrounding forests are protected by the Stevenson Memorial Reserve and Mount Vaea Scenic Reserve Ordinance. +685 6 3500 (Tourist Information) Off Cross Island Road, Apia To-Sua海沟 "Aquamarine Paradise" Right in the middle of a forested sprawl is a gaping swimming hole, filled with gorgeous aquamarine water that simply demands diving into. This stunning attraction is located on the island of Upolu. Visitors must descend a ladder to reach the diving point, from where they can plunge into epic crystalline waters below. by Rickard Törnblad +685 4 1699 www.to- tosua.oceantrench@gmail. Main South Coast Road, suaoceantrench.com/ com Apia 罗伯特·路易斯·史蒂文森博物馆 "A Poetic Tour" Catch a glimpse into the life and work of Scottish poet Robert Louis Stevenson at this beautiful, well-preserved museum, where this legendary literary figure spent the last few years of his life. -

Melancholia and Conviviality in Modern Literary Scots: Sanghas, Sengas and Shairs1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository Melancholia and Conviviality in Modern Literary Scots: Sanghas, Sengas and Shairs1 Sometimes I wonder if I belong to a country of the imagination. Outside it, I’m expected to explain, dismantle stereotypes, or justify my claim to being Scottish. […] These folk make me explain my species of Scottishness. A Hebridean, Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland, Scots-speaking father, who both spoke English. […] They raised four children between two cultures, three languages, surrounded by a wealth of domestic, social, religious, cultural and political paradoxes. (Bennett 2002: 18–19) In Postcolonial Melancholia, Paul Gilroy argues that ‘though the critical orientation toward our relation with our racial selves is an evasive thing, often easier to feel than to express, it does have important historical precedents’ (2005: 38). As Margaret Bennett’s remark above demonstrates, attempting to define one’s racial and cultural origins may quickly raise further questions about language, religion, socio-economic status and how those things came to be. Gilroy articulates a post-imperial Britain in which ‘a variety of complicated subnational, regional and ethnic factors has produced an uneven pattern of national identification, of loss and of what might be called an identity-deficit’ (2011: 190). Responses to this situation are observable in society and in the arts, and although Gilroy’s critiques are often scathing, he also recognises ‘spontaneous, convivial culture’ through which Britain has been able to ‘discover a new value in its ability to live with alterity without becoming anxious, fearful or violent’ (Gilroy 2005: xv).