The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: a Survey and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

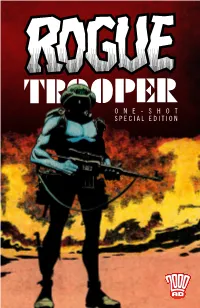

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

“War of the Worlds Special!” Summer 2011

“WAR OF THE WORLDS SPECIAL!” SUMMER 2011 ® WPS36587 WORLD'S FOREMOST ADULT ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 25, 2011 SUMMER 2011 $6.95 HM0811_C001.indd 1 5/3/11 2:38 PM www.wotw-goliath.com © 2011 Tripod Entertainment Sdn Bhd. All rights reserved. HM0811_C004_WotW.indd 4 4/29/11 11:04 AM 08/11 HM0811_C002-P001_Zenescope-Ad.indd 3 4/29/11 10:56 AM war of the worlds special summER 2011 VOlumE 35 • nO. 5 COVER BY studiO ClimB 5 Gallery on War of the Worlds 9 st. PEtERsBuRg stORY: JOE PEaRsOn, sCRiPt: daVid aBRamOWitz & gaVin YaP, lEttERing: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, aRt: PuPPEtEER lEE 25 lEgaCY WRitER: Chi-REn ChOOng, aRt: WankOk lEOng 59 diVinE Wind aRt BY kROmOsOmlaB, COlOR BY maYalOCa, WRittEn BY lEOn tan 73 thE Oath WRitER: JOE PEaRsOn, aRtist: Oh Wang Jing, lEttERER: ChEng ChEE siOng, COlORist: POPia 100 thE PatiEnt WRitER: gaVin YaP, aRt: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, COlORs: ammaR "gECkO" Jamal 113 thE CaPtain sCRiPt: na'a muRad & gaVin YaP, aRt: slaium 9. st. PEtERsBuRg publisher & editor-in-chief warehouse manager kEVin Eastman JOhn maRtin vice president/executive director web development hOWaRd JuROFskY Right anglE, inC. managing editor translators dEBRa YanOVER miguEl guERRa, designers miChaEl giORdani, andRiJ BORYs assOCiatEs & JaCinthE lEClERC customer service manager website FiOna RussEll WWW.hEaVYmEtal.COm 413-527-7481 advertising assistant to the publisher hEaVY mEtal PamEla aRVanEtEs (516) 594-2130 Heavy Metal is published nine times per year by Metal Mammoth, Inc. Retailer Display Allowances: A retailer display allowance is authorized to all retailers with an existing Heavy Metal Authorization agreement. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities Illustration from Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde Based on the series Graphic Classics published by Magic Wagon, a division of ABDO. 1-800-800-1312 • www.abdopublishing.com Not for resale • Photocopy and adapt as needed for classroom and library use. Table Of Contents Comic book text is short, but that doesn’t mean students don’t learn a lot from it! Comic books and graphic novels can be used to teach reading processes and writing techniques, such as pacing, as well as expand vocabulary. Use this PDF to help students get more out of their comic book reading. Here are some of the projects you can give to your students to make comics educational and enjoyable! General Activities Publication History & Research --------------------------------- 1 Book vs. Movie vs. Graphic Novel ----------------------------- 2 Shared Reading & Fluency Practice --------------------------- 3 Scary Horror Stories ------------------------------------------------ 4 Create a Ghost Story ---------------------------------------------- 4 Work with Your Library -------------------------------------------- 5 Activities For Each Story The Creature from the Depths ---------------------------------- 6 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde -------------------------------------------- 7 Frankenstein ----------------------------------------------------------- 8 The Legend of Sleepy Hollow ----------------------------------- 9 Mummy ------------------------------------------------------------------ 10 Werewolf ---------------------------------------------------------------- -

Original Text Publisher: Classical Comics Ltd Author: William Shakespeare

New Title Information Classical Comics Ltd., PO Box 7280, Litchborough, Towcester NN12 9AR. Tel: 0845 812 3000 Fax: 0845 812 3005 Email: [email protected] www.classicalcomics.com Title: The Tempest The Graphic Novel Sub title: Original Text Publisher: Classical Comics Ltd Author: William Shakespeare ISBN: UK: 978-1-906332-29-7 US: 978-1-906332-69-3 Contributors: Script Adaptation: John McDonald Pencils: Jon Haward Inks: Gary Erskine Colouring & lettering: Nigel Dobbyn Design & Layout: Jo Wheeler Editor in Chief: Clive Bryant Brief description of the book: This is the unabridged play brought to life in full colour! Ideal for purists, students and readers who will appreciate the unaltered text. Although The Tempest Folio printing of Shakespeare's plays, it was almost certainly the last play he wrote alone. It held pride of place in that crowning glory to the career of the most brightest of playwrights. Needless to say, we had to select the very best artists to do it justice, and to bring you the stunning artwork that you've come to expect from our titles. Poignant to the last, this book is a classic amongst classics. Coupled with stunning artwork, this is a must-have for any Shakespeare lover. Key sales points: • ENTIRE, UNABRIDGED ORIGINAL SCRIPT - just as The Bard intended. Ideal for purists, students and for readers who want to experience the unaltered text. • Full colour graphic novel format. • Meets UK curriculum requirements. • Teachers notes/study guide available. Publisher information: Classical Comics is a UK publisher creating graphic novel adaptations of classical literature. True to the original vision of the author, the book has been further experience. -

Libro Gratis Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics)

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics) PDF DRACULA, 2 (GRAPHIC CLASSICS) Tapa blanda Abreviado, 2 junio 2020 Author : Descripcin del productoBiografa del autorAbraham 'Bram' Stoker (1847 - 1912) was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and joined the Irish Civil Service before his love of theatre led him to become the unpaid drama critic for the Dublin Mail. He went on to act as as manager and secretary for the actor Sir Henry Irving, while writing his novels, the most famous of which is Dracula. Abraham (Bram) Stoker was an Irish writer, best known for his Gothic classic Dracula, which continues to influence horror writers and fans more than 100 years after it was first published.Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, in science, mathematics, oratory, history, and composition, Stoker's writing was greatly influenced by his father's interest in theatre and his mother's gruesome stories ... I collect graphic novels based on classic literature, so I had high hopes for this series by Barron's. In addition to Dracula, they've also published Treasure Island, Frankenstein, Kidnapped, Moby-Dick, and Journey to the Center of the Earth (maybe others I'm unaware of too). 'Dracula (Dover Graphic Novel Classics)' is a faithful adaptation of the novel told in graphic novel format. As a bonus, all the art is presented black and white so that it can be colored. It's all here. The creepy castle and creepier Count Dracula. The Harkners, Van Helsing and Renfield. The dark and tragic death. This item: Dracula Graphic Novel (Illustrated Classics) by Bram Stoker Paperback $9.95. -

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Narratives in Comics1

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Narratives in Comics1 Derek Parker Royal Classic works of American literature have been adapted to comics since the medium, especially as delivered in periodical form (i.e., the comic book), first gained a pop cultural foothold. One of the first texts adapted by Classic Comics, which would later become Classics Illustrated,2 was James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, which appeared in issue #4, published in August 1942. This was immediately followed the next month by a rendering of Moby-Dick and then seven issues later by adaptations of two stories by Washington Irving, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Headless Horseman.”3 As M. Thomas Inge points out, Edgar Allan Poe was one of the first, and most frequent, American authors to be translated into comics form (Incredible Mr. Poe 14), having his stories adapted not only in early issues of Classic Comics, but also in Yellow- jacket Comics (1944–1945) and Will Eisner’s The Spirit (1948).4 What is notable here is that almost all of the earliest adaptations of American literature sprang not only from antebellum texts, but from what we now consider classic examples of literary romance,5 those narrative spaces between the real and the fantastic where psychological states become the scaffolding of national and historical morality. It is only appropriate that comics, a hybrid medium where image and text often breed an ambiguous yet pliable synthesis, have become such a fertile means of retelling these early American romances. Given this predominance of early nineteenth-century writers adapted to the graphic narrative form, it is curious how one such author has been underrepresented within the medium, at least when compared to the treatment given to his contemporaries. -

Comic Book Club Handbook

COMIC BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for comics and graphic novels! STAFF COMIC BOOK LEGAL Charles Brownstein, Executive Director Alex Cox, Deputy Director DEFENSE FUND Samantha Johns, Development Manager Kate Jones, Office Manager Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Betsy Gomez, Editorial Director protecting the freedom to read comics! Our work protects Maren Williams, Contributing Editor readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor tors who face the threat of censorship. We monitor legislation Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. BOARD OF DIRECTORS We create resources that promote understanding of com- Larry Marder, President ics and the rights our community is guaranteed. Every day, Milton Griepp, Vice President Jeff Abraham, Treasurer we publish news and information about censorship events Dale Cendali, Secretary as they happen. We are partners in the Kids’ Right to Read Jennifer L. Holm Project and Banned Books Week. Our expert legal team is Reginald Hudlin Katherine Keller available at a moment’s notice to respond to First Amend- Paul Levitz ment emergencies. CBLDF is a lean organization that works Andrew McIntire hard to protect the rights that our community depends on. For Christina Merkler Chris Powell more information, visit www.cbldf.org Jeff Smith ADVISORY BOARD Neil Gaiman & Denis Kitchen, Co-Chairs CBLDF’s important Susan Alston work is made possible Matt Groening by our members! Chip Kidd Jim Lee Frenchy Lunning Join the fight today! Frank Miller Louise Nemschoff http://cbldf.myshopify Mike Richardson .com/collections William Schanes José Villarrubia /memberships Bob Wayne Peter Welch CREDITS CBLDF thanks our Guardian Members: Betsy Gomez, Designer and Editor James Wood Bailey, Grant Geissman, Philip Harvey, Joseph Cover and interior art by Rick Geary. -

British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2013 Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Salisbury, Derek, "Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books" (2013). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 209. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. -

Shakespeare and Contemporary Adaptation: the Graphic Novel

SHAKESPEARE AND CONTEMPORARY ADAPTATION: THE GRAPHIC NOVEL By MARGARET MARY ROPER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with Integrated Studies The Shakespeare Institute College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham December 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the process of adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays into the graphic novel medium. It traces the history of these adaptations from the first comic books produced in the mid-twentieth century to graphic novels produced in the twenty-first century. The editions used for examination have been selected as they are indicative of key developments in the history of adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays into the medium. This thesis explores how the plays are presented and the influences on the styles of presentation. It traces the history of the form and how the adaptations have been received in various periods. It also examines how the combination of illustrations and text and the conventions of the medium produce unique narrative capacities, how these have developed over time and how they used to present the plays. -

Criminals Clone Wars Fan Sourcebook

Criminals Clone Wars Fan Sourcebook RYAN BROOKS, KEITH KAPPEL ©2009 Fandom Comics and ® & ™ where indicated. All rights re- Credits served. All material contained within this document not already under ownership of seperate parties are intellectual property of Fandom Comics. WRITERS Keith Kappel The Wizards of the Coast logo is a registered trademark owned by Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Original document design created by Wizards of the Coast, Inc. EDITORS Ryan Brooks, Keith Kappel The d20 System logo and d20 are trademarks owned by Wizards of the Coast, Inc. DESIGN Ryan Brooks Star Wars® and all related material are trademarks of LucasFilm Ltd. or their respective trademark and copyright holders. Unless WEB PRODUCTION Ryan Brooks otherwise stated, all original material held within this document is intellectual property of Fandom Comics. Fandom Comics is not affiliated in any way to LucasFilm, Ltd. or Wizards of the Coast, chapter V Brian Ching, Cam Kennedy, Inc. Fillbach Brothers, Genndy Tartakovsky, Grant Gould, Jan Duursema, LucasArts, LucasFilm LTD., Luke Ross, Some rules mechanics are based on the Star Wars Roleplaying OFFICIAL ARTWORK Penny-arcade.com, Ramón K. Pérez Game Revised Core Rulebook by Bill Slavicsek, Andy Collins, and JD Wiker, the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® rules created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and the new DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® game designed by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, 2 Allies and opponents Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkinson. Criminals Any similarities to actual people, organizations, places or events are purely coincidental. This document is not intended for sale and may not be altered, reproduced, or redistributed in any way without written consent from Fandom Comics. -

Shakespeare in Graphic Novels

Shakespeare in Graphic Novels Shakespeare is available in many mediums and with many variations, including graphic novels. Here are some various forms of Shakespeare available in graphic novels: Shakespeare in Direct re-telling of Shakespearean plays Graphic Novels Adaptations of plays The use of Shakespearean characters GNs about or featuring Shakespeare himself By Lindsay Parsons What are graphic novels? Benefits of Graphic Novels Graphic novels (GN for short) are essentially comics bound into a book. For Engage reluctant readers and readers who are more visually oriented many years graphic novels have been Faster to read, therefore teens can banned from classrooms because of the pick one up anytime negative stigma that they are a ‘dumbed- Great for teens learning a new language because images provide down’ book. That is now changing and context many teachers are incorporating GNs into Helps expand vocabulary and their curriculum, (Méndez, 2004). understanding of storylines Strong appeal factor for YA Why add Graphic Novels to your audiences, (Méndez, 2004) collection? Contrary to some beliefs, graphic novels Graphic novels appeal to a wide do not discourage reading books in text variety of readers Many different genres are available format, they actually encourage it. Graphic Graphic novels help develop literacy novels also require an expanded use of skills cognitive skills to understand the dialogue in Provides a visual form of literature the literature, (Schwarz, 2002). Therefore, that allow readers to expand their interpretation, (Schwarz, 2006) providing teens with Shakespearean graphic 14 novels can spark an interest in Shakespeare becoming increasingly popular, especially in and a broader comprehension of his work.