Among the Csango Hungarians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

A Concise History of Hungary

A Concise History of Hungary MIKLÓS MOLNÁR Translated by Anna Magyar published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru, UnitedKingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org Originally publishedin French as Histoire de la Hongrie by Hatier Littérature Générale 1996 and© Hatier Littérature Générale First publishedin English by Cambridge University Press 2001 as A Concise History of Hungary Reprinted 2003 English translation © Cambridge University Press 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception andto the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Printedin the UnitedKingdomat the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Sabon 10/13 pt System QuarkXPress™ [se] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 66142 0 hardback isbn 0 521 66736 4 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page viii Acknowledgements xi Chronology xii 1 from the beginnings until 1301 1 2 grandeur and decline: from the angevin kings to the battle of mohács, 1301–1526 41 3 a country under three crowns, 1526–1711 87 4 vienna and hungary: absolutism, reforms, revolution, 1711–1848/9 139 5 rupture, compromise and the dual monarchy, 1849–1919 201 6 between the wars 250 7 under soviet domination, 1945–1990 295 8 1990, a new departure 338 Bibliographical notes 356 Index 357 ILLUSTRATIONS plates 11. -

HSR Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018)

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) In this volume: Jason Kovacs reviews the history of the birth of the first Hungarian settlements on the Canadian Prairies. Aliaksandr Piahanau tells the story of the Hungarian democrats’ relations with the Czechoslovak authorities during the interwar years. Agatha Schwartz writes about trauma and memory in the works of Vojvodina authors László Végel and Anna Friedrich. And Gábor Hollósi offers an overview of the doctrine of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Plus book reviews by Agatha Schwartz and Steven Jobbitt A note from the editor: After editing this journal for four-and-a-half decades, advanced age and the diagnosis of a progressive neurological disease prompt me to resign as editor and producer of this journal. The Hungarian Studies Review will continue in one form or another under the leadership of Professors Steven Jobbitt and Árpád von Klimo, the Presidents res- pectively of the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and the Hungarian Studies Association (of the U.S.A.). Inquiries regarding the journal’s future volumes should be directed to them. The contact addresses are the Departments of History at (for Professor Jobbitt) Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, RB 3016, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, P7B 5E1. [email protected] (and for Prof. von Klimo) the Catholic University of America, 620 Michigan Ave. NE, Washing- ton DC, USA, 20064. [email protected] . Nándor Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) Contents Articles: The First Hungarian Settlements in Western Canada: Hun’s Valley, Esterhaz-Kaposvar, Otthon, and Bekevar JASON F. -

Download (2MB)

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 7 No. 1 2018 Ethnonyms in Europe and Asia: Studies in History and Anthropology Zsuzsanna Zsidai Special Editor of the Thematic Issue Contents WALTER POHL Ethnonyms and Early Medieval Ethnicity: Methodological Reflections 5 ODILE KOMMER, SALVATORE LICCARDO, ANDREA NOWAK Comparative Approaches to Ethnonyms: The Case of the Persians 18 ZSUZSANNA ZSIDAI Some Thoughts on the Translation and Interpretation of Terms Describing Turkic Peoples in Medieval Arabic Sources 57 GYÖRGY SZABADOS Magyar – A Name for Persons, Places, Communities 82 DÁVID SOMFAI KARA The Formation of Modern Turkic ‘Ethnic’ Groups in Central and Inner Asia 98 LÁSZLÓ KOppÁNY CSÁJI Ethnic Levels and Ethnonyms in Shifting Context: Ethnic Terminology in Hunza (Pakistan) 111 FEATURED REVIEW A szovjet tényező: Szovjet tanácsadók Magyarországon [The Soviet factor: Soviet advisors in Hungary]. By Magdolna Baráth. Reviewed by Andrea Pető 136 http://www.hunghist.org tartalomjegyzek.indd 1 5/29/2018 2:40:48 PM Contents BOOK REVIEWS “A Pearl of Powerful Learning:” The University of Cracow in the Fifteenth Century. By Paul W. Knoll. (Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, 52.) Reviewed by Borbála Kelényi 142 Writing History in Medieval Poland: Bishop Vincentius of Cracow and the Chronica Polonorum. Edited by Darius von Güttner-Sporzyński. (Cursor Mundi 28.) Reviewed by Dániel Bagi 145 Kaiser Karl IV. 1316–2016. Ausstellungskatalog Erste Bayerisch-Tschechische Landesausstellung. Edited by Jiří Fajt and Markus Hörsch. Reviewed by Balázs Nagy 148 The Art of Memory in Late Medieval Central Europe (Czech Lands, Hungary, Poland). By Lucie Doležalová, Farkas Gábor Kiss, and Rafał Wójcik. -

A Gangesz Partjától a Hunyadiak Hollójáig. Petőfi, Arany És Ady

Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények (ItK) 122(2018) HALMÁGYI MIKLÓS A Gangesz partjától a Hunyadiak hollójáig Petőfi, Arany és Ady történelmi témájú műveinek középkori forráshátteréhez1 Történelmi tárgyú szépirodalmi műveket tanulmányozva fölvetődhet a kérdés: milyen forrásra vezethető vissza az, ami a műalkotásban olvasható? Miként vált a történelmi forrásból szépirodalom? A források ismerete a műalkotás befogadásához is többletél- ményt nyújthat, gazdagabbá teheti az értelmezési lehetőségek körét. Az alábbiakban történelmi témájú magyar szépirodalmi művek forráshátterét vizsgálom, figyelmet for- dítva arra az átalakulásra, ahogy a források ismerete művészetté kristályosodik. „Jöttem a Gangesz partjairól…” India mint őshaza? Ady Endre A Tisza parton című versének jól ismert, nagy erejű kezdősora ez. Bizo- nyára többen fölteszik a kérdést: miért érkezik a vers beszélője éppen a Gangesz folyó partjáról, Indiából? Hogy kerül egy magyar költő Indiába? Adódhat a válasz: sajátos őstörténeti eredettudat állhat Ady verssora mögött.2 A probléma azonban ezzel nem oldódik meg. Fönnáll a kérdés: ismerünk-e olyan eredethagyományt, mely a Gangesz vidékéről származtatta volna a magyarokat? Nem vállalkozom rá, hogy megoldom a kérdést, de szeretném felhívni a figyelmet néhány válaszlehetőségre. A téma tárgyalá- sa lehetőséget ad arra is, hogy a középkori magyar hagyomány indiai vonatkozására is rámutassunk. Ady költészete sokarcú líra. Írt szilaj, háborgó költeményeket, más műveiben azonban a lelki béke iránti vágyat, az Istennel való kibékülés vágyát fejezi ki. Egyes műveiben szembeszáll a keresztény vallással, pogány hitvilág után vágyódik, másutt azonban he- lyet kap költészetében a Krisztus iránti tisztelet. Pogány verseit a fájdalom tüneteként, panaszként érthetjük. Ezek közé sorolható a Lótusz című vers is, mely először 1902-ben látott nyomdafestéket, 1903-ban pedig helyet kapott Méga egyszer című kötetben.3 * A szerző középkortörténész, irodalomtörténész, PhD (2014). -

Anonymus 7.Indd

JUHÁSZ PÉTER ANONYMUS: FIKCIÓ ÉS REALITÁS. AZ ÁLMOS-ÁG HONFOGLALÁSA JUHÁSZ PÉTER ANONYMUS: FIKCIÓ ÉS REALITÁS. AZ ÁLMOS-ÁG HONFOGLALÁSA 2019 A könyv megjelenését támogatta Borítóterv: Majzik Andrea Lektorálta: prof. dr. Veszprémy László ISBN 978-615-5372-96-4 [print] ISBN 978-615-5372-97-1 [online PDF] © Juhász Péter, 2019 © Belvedere Meridionale, 2019 Tartalom Prológus ............................................................................................................. 7 A Gesta kézirata és szerkezete ........................................................................... 9 A Gesta Hungar(or)um – történetírás vagy irodalom? ..................................... 16 Anonymus írói módszerei. A krónikák történelme és Anonymus története .....19 Anonymus és az „ősgeszta” ............................................................................. 21 A Gesta stílusának forrásai A 12. századi francia reneszánsz és a honfoglalók felfedezése ....................... 33 Hivatalnok vagy irodalmár? A hivatalos írásbeliség és a Gesta ...................... 41 Oklevélformulák a Gestában ............................................................................ 44 A Gesta társadalmi ideálja: ellentmondó magyarázatok .................................. 48 A Gesta névanyaga: helyszínek és szereplők ................................................... 53 A Gesta jogi felfogása. Szuverenítás és jogos foglalás ................................... 68 A korhatározás sarokpontjai. A 12. századi Kelet-Európa a Gestában ............73 Gloriosissimus -

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

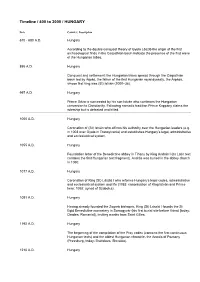

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

![XI–XIII. Század Közepe) [The Writing and Writers of History in Árpád- Era Hungary, from the Eleventh Century to the Middle of the Thirteenth Century]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7540/xi-xiii-sz%C3%A1zad-k%C3%B6zepe-the-writing-and-writers-of-history-in-%C3%A1rp%C3%A1d-era-hungary-from-the-eleventh-century-to-the-middle-of-the-thirteenth-century-2187540.webp)

XI–XIII. Század Közepe) [The Writing and Writers of History in Árpád- Era Hungary, from the Eleventh Century to the Middle of the Thirteenth Century]

Hungarian Historical Review 10, no. 1 (2021): 155–159 BOOK REVIEWS Történetírás és történetírók az Árpád-kori Magyarországon (XI–XIII. század közepe) [The writing and writers of history in Árpád- era Hungary, from the eleventh century to the middle of the thirteenth century]. By László Veszprémy. Budapest: Line Design, 2019. 464 pp. The centuries following the foundation of the Christian kingdom of Hungary by Saint Stephen did not leave later generations with an unmanageable plethora of written works. However, the diversity of the genres and the philological and historical riddles which lie hidden in these works arguably provide ample compensation for the curious reader. There are numerous textual interrelationships among the Gesta Hungarorum by the anonymous notary of King Béla known as Anonymus, the Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum by Simon of Kéza and the forteenth-century Illuminated Chronicle consisting of various earlier texts, not to mention the hagiographical material on the canonized rulers. For the historian, the relationships among these early historical texts and the times at which they were composed (their relative and absolute chronology) are clearly a matter of interest, since the judgment of these links affects the credibility of the historical information preserved in them. In an attempt to establish the relative chronology, philological analysis is the primary tool, while in our efforts to determine the precise times at which the texts were composed, literary and legal history may offer the most reliable guides. László Veszprémy has very clearly made circumspect use of these methods in his essays, thus it is hardly surprising that many of his colleagues, myself included, have been eagerly waiting for his dissertation, which he defended in 2009 for the title of Doctor of Sciences, to appear in the form of a book in which the articles he has written on the subject since are also included. -

The White Horse Press Climatic Changes in the Carpathian Basin

The White Horse Press Climatic Changes in the Carpathian Basin during the Middle Ages. The State of Research András Vadas, Lajos Rácz Global Environment 12 (2013): 198–227 The aim of the paper is to present a summary of the current scholarship on the climate of the Carpathian Basin in the Middle Ages. It draws on the results of three substantially differing branches of science: natural sciences, archaeology and history are all taken into consideration. Based on the most important results of the recent decades different climatic periods can be identified in the scholarship. The paper attempts to summarize the different view of these major climatic periods. Based on present scholarship the milder climate of the Roman Period was followed by a cooler period from the 4th century, attested by both historical and natural-historical sources, and apparently climate had also become drier. The cool period of the Great Migrations concluded in the Carpathian Basin between the end of the 7th and the turn of the 8th-9th centuries. The winters in the first half of the 9th century were probably milder. In the warmer medieval period (called Medieval Climatic Anomaly in recent scholarship) winters had clearly become milder and summers warmer, while the climate was probably still dry. The first cooling signs of the “Little Ice Age” had already become apparent in the 13th century, but the cold and rainy character of the climate could only become dominant in the Carpathian Basin in the early 14th century, which then, albeit with great anomalies, endured until the second half of the 19th century. -

From the Anonymous Gesta to the Flight of Zalán by Vörösmarty*

chapter 5 From the Anonymous Gesta to the Flight of Zalán by Vörösmarty* János M. Bak My initial question was: why did the Hungarians, well known for politicizing history and historicizing politics,1 not produce some spectacular forgeries (or confabulations) around 1800 to boost national consciousness.2 There must have been several reasons for this. Maybe among the Hungarians there was more of a continuity of national memory of heroic past and of tragic defeats than elsewhere. While Hungary had become part of the Habsburg monarchy centuries before and rebellions against this failed, the status of the kingdom within the empire was by no means similar to that of nationalities without political rights in need of establishing a national identity, true or false. And, although, for example, the Bohemian aristocracy had a strong voice in Vienna, the Czechs felt themselves overwhelmed by the Germans and seemed in need of a new mythical past of their nation, more so than the Magyars.3 Whatever the case may be, I dare answer my rhetorical question by pointing to the dis- covery and popularization of the “Deeds of the Hungarians” by an anonymous notary of the medieval royal court, published in the mid-eighteenth century. * I should like to express my thanks to my fellow fellow Péter Dávidházi for referring me to the exciting contemporary writings (including his own) on Vörösmarty and his age. 1 For the contemporary aspect of this, see my “Die Mediävisierung der Politik im Ungarn des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts,” in Umkämpfte Vergangenheit: Geschichtsbilder, Erinnerung und Vergangenheitspolitik im internationalen Vergleich, Petra Bock & Edgar Wolfrum (eds.), (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1999) (Sammlung Vandenhoeck), 103–13. -

Hungary Part 2 “Culture Specific” Describes Unique Cultural Features of Hungarian Society

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Hungarian military member Rosie the Riveter, right, is considered a symbol of American feminism). ECFG The guide consists of two parts: Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Eastern Europe. Hungary Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Hungarian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: Hungarian Brig Gen Nándor Kilián, right, chats with USAF Brig Gen Todd Audet). For further information, contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected] or visit the AFCLC website at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Timeline / 400 to 1725 / HUNGARY

Timeline / 400 to 1725 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia).