The New Yorker January 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist C.V. (PDF)

WALTON FORD BORN IN LARCHMONT, NEW YORK 1960 LIVES AND WORKS IN NEW YORK, NEW YORK EDUCATION 1982 BFA, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI European Honors Program, Rhode Island School of Design, Rome, Italy SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 “Walton Ford: Barbary,” Kasmin, New York, NY “Walton Ford: New Watercolors,” Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz, Switzerland 2017 “Walton Ford: Calafia,” Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA 2015-16 “Walton Ford,” Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris, France 2014 “Watercolors,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2011 “I don't like to look at him, Jack. It makes me think of that awful day on the island,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2010 “Walton Ford: Bestiarium,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark; Hamburger Bahnhof Museum fur Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany and Albertina, Vienna, Austria 2009 “Walton Ford: New Work,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2008 “Walton Ford,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2007 "Tigers of Wrath: Watercolors by Walton Ford" Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio, TX 2006 “Tigers of Wrath: Watercolors by Walton Ford,” Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY “Walton Ford: Works on Paper,” John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2005 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2004 “Bitter Gulfs,” Paul Kasmin Gallery at 511, New York, NY New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2002 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY “Brutal Beauty,” Bowdin -

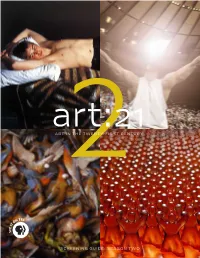

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Tigers of Wrath:Watercolors by Walton Ford

Walton Ford (American, born 1960). Falling Bough, 2002. Watercolor, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery Educator packet for the special exhibition Tigers of Wrath: Watercolors by Walton Ford on view at the Brooklyn Museum, November 3, 2006–January 28, 2007 narrative—the passenger pigeons are attacking each other and their young as the branches crash to the ground. Falling Bough The works in Tigers of Wrath are watercolors; the animals depicted are life- scale (another legacy from Audubon) and are often surrounded by notes, the American History and Natural History Latin names for the animals, and the artwork’s title. Questions for Viewing Content recommended for Middle and High School students What is going on in this image? Describe the types of animals and the landscape. Description What are the birds doing? Zoom in on different sections of the branch. In this large watercolor painting, passenger pigeons alight from a huge falling branch. The birds that are clustered on the bough are attacking each Ford has commented on the dreamlike state of his scenes. What seems other, knocking over nests, destroying eggs—all as the branch is falling to the ground. In the background there are other flocks of passenger pigeons unreal in this image? Why? and snapped branches and trees. Ford is inspired by Audubon’s writing as well as his artwork. Read the excerpt The passenger pigeon constituted a third of the natural birds in North from Audubon in Description. Compare and contrast the written text with America when European colonists arrived, but by the early twentieth century, Falling Bough. -

Walton Ford Grew up in the Hudson Valley and Currently Lives and Works in New York

WALTON FORD Walton Ford grew up in the Hudson Valley and currently lives and works in New York. He first studied film at the Rhode Island School of Design before focusing solely on painting. Inspired by the work of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Ford’s engage- ment with historical subject matter imbues his large-scale watercolors with an old-world feel. He can often be found at the American Museum of Natural History sketching animal anatomy and relishing in the picturesque dioramas. Public collections include the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. Ford’s solo exhibitions include Tigers of Wrath: Watercolors by Walton Ford, at the Brooklyn Museum, New York; Walton Ford: Bestiarium, which opened at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin and traveled to the Albertina, Vienna, and Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark; Walton Ford, at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris. Vito Schnabel Gallery presented New Watercolors in St. Moritz in March 2018. Ford lives and works in New York. WALTON FORD B.1960, HUDSON VALLEY, NY LIVES AND WORKS IN GREAT BARRINGTON, MA 1982 BFA, RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL FOR THE ARTS, PROVIDENCE, RI SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Walton Ford: Aquarelle, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany 2018 Walton Ford: Barbary, Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY Walton Ford: New Watercolors, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz, Switzerland 2017 Walton Ford: Calafia, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2016 Naturalia, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2015 Walton Ford, Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris, France Walton Ford, Hôtel de Mongelas, Paris, France 2014 Walton Ford: Watercolors, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Walton Ford, I Don’t Like To Look At Him, Jack. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture PLANTAE, ANIMALIA, FUNGI: TRANSFORMATIONS OF NATURAL HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN ART A Dissertation in Art History by Alissa Walls Mazow © 2009 Alissa Walls Mazow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The Dissertation of Alissa Walls Mazow was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Richard M. Doyle Professor of English, Science, Technology and Society, and Information Science and Technology Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the ways that five contemporary artists—Mark Dion (b. 1961), Fred Tomaselli (b. 1956), Walton Ford (b. 1960), Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and Cy Twombly (b. 1928)—have adopted the visual traditions and theoretical formulations of historical natural history to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture” and begin new dialogues about emerging paradigms, wherein plants, animals and fungi engage in ecologically-conscious dialogues. Using motifs such as curiosity cabinets and systems of taxonomy, these artists demonstrate a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history. For these practitioners natural history operates within the realm of history, memory and mythology, inspiring them to make works that examine a scientific paradigm long thought to be obsolete. This study, which itself takes on the form of a curiosity cabinet, identifies three points of consonance among these artists. -

Walton Ford Calafia

G A G O S I A N October 5, 2017 WALTON FORD CALAFIA Opening reception: Thursday, November 2, 6–8PM November 2–December 16, 2017 456 North Camden Drive Beverly Hills, CA 90210 It’s a sort of attraction-repulsion thing, beautiful to begin with until you notice that some sort of horrible violence is about to happen, or is in the middle of happening. ―Walton Ford Gagosian is pleased to present “Calafia,” new watercolor paintings by Walton Ford. This is his first exhibition with the gallery. Page 1 of 3 G A G O S I A N Ford’s work explores where natural history and human culture intersect. His large-scale, empirically precise, and highly detailed paintings consider the drama and history of animals as they exist in the human imagination, revealing the deeply intertwined relationships between nature and civilization. Using the visual language and medium of nineteenth century naturalist illustrators such as John James Audubon, Ford masters the aesthetics of scientific truth only to amplify and subvert them, creating provocative, and sometimes fanciful narratives out of facts. “Calafia” comprises a new series of epic paintings in which Ford depicts California through an amalgam of its myths, legends, and folklore. In a sixteenth century novel, Las sergas de Esplandían (The Adventures of Esplandian), the Castilian author Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo wrote of a fictitious island, inhabited by enormous flying griffins. On this island lived a tribe of Amazons, ruled by a warrior queen named Calafia. When the Spanish sailed up the western coast of North America, they named the land after this same imaginary island they had read about— thus fiction became history. -

Brutal Beauty: Paintings by Walton Ford

PAINTINGS BY WALTON FORD Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine ^ This catalosfiic accDinpanics iIk- cxhiliition ol the same name at the Bdwdoin College Museum of .\rt, Brunswick, Maine, September 29 - December 10, 2000. Lenders to the exhibition: Bill .-Vrning Rogers Beasley Janice and Mickey Cartin Madison Cox Beth Rudin De\\bod\ Bruce AIKti F.issner and Judith Pick Eissner Jerald Dillon Fcsscnden Xicole Klagsbrun Martin Kline Laura-Lee VV. Woods Private collection, courtesy Paul Kasnun (nillery Special Collections & .\rchives, Bowdoin College Libran' United \arn Products Oimpany, Inc., New Jersc\- University Art Museum, ("alifornia State L^niversity, Long Beach .%ion\iiious lenders Bnitiil Bciiiit)': Piiiiitiiii^f h\ Wiiltdii Font is supported b\- the Stevens L. Frost Endowment F'und, the George Otis Hamlin F'und, and the Elizabeth B. G. Hamhn Fund. Cover illustration: The Hoiiseboldei\ 1997 oil on wood panel, 6? x 46 inches Courtesy Janice and Mickey Cartin Endsheets: landscape detail from Chalo, Chalo, Chalo!, 1997 watercolor, gouache, pencil and ink on paper 59 1/2 X 40 'A inches Courtesy Bruce ••Mlyn Eissner and Judith Pick Eissner Photography: .Vdam Reich; cover, pp. 17, ly, 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29 Dennis Griggs; pp. 8 and 14 Courtesy Paul Kasmin Ciallen.'; pp. 4 and 30 C'atalogue design: Judy Kohn, Kohn CruiLshank, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts Printing: Champagne Lafayette Communications Inc. Natick, .Massachusetts (xjpyright © 2000 Bowdoin College ISBN: 916606-32-5 — Paintings by Walton Ford it possible to observe the stylistic similarities between is the largest exhibition of Walton Ford's work to date the work of Audubon and Ford but will allow us to pick out and focuses on his briUiant, sometimes biting paintings of some of Ford's direct quotes from Audubon's works. -

Heroic Painting

HEROI F36 12:H55 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/heroicpaintingfeOOIubo EROIC PAINI ING FEBRUARY 3 - APRIL 21, 1996 SECCA SOUTHEASTERN CENTER FOR CONTEMPORARY ART Sara Lee Corporation is the corporate sponsorfor this exhibition ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A number of people helped me understand the Douglas Bohr, installations manager/registrar, and evolving notion of the hero that is explored in Karin Lusk, executive administrative assistant, "Heroic Painting." They work in diverse fields from coordinated the research and administration of the social services to the arts, but all in some way installation and catalogue. Their contribution far interface with the heroic acts of daily life. I am exceeded the parameters of their jobs. I would also grateful to Gayle Dorman, Suzi Gablik, Connie like to acknowledge Jeff Fleming, curator; AngeUa Grey, Nan Holbrook, Basil Talbott, and Emily Debnam, programs administrative assistant; and Wilson for their input. Mel White, programs assistant. Thanks are also due to Ruth Beesch, director of Finally, I am indebted to the artists for providing the Weatherspoon Art Gallery, for helping me in insights on their work and to the lenders for their my search for women artists. SECCA's staff worked generosity. diligently on many aspects of the exhibition. — S.L. This publication accompanies the exhibition EXHIBITION TOUR: "HEROIC PAINTING" Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, Florida May 5 - June 30, 1996 February 3 - April 21, 1996 Queens Museum of Art, New York at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, July 19 - September 8, 1996 Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Knoxville Museum of Art, ICnoxville, Tennessee October 11, 1996 - January 12, 1997 SECCA is supported by The Arts Council of Winston-Salem and Forsyth County, and the The Contemporary Arts Center, North Carolina Arts Council, a state agency. -

Lowbrow Art : the Unlikely Defender of Art History's Tradition Joseph R

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2013 Lowbrow art : the unlikely defender of art history's tradition Joseph R. Givens Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Givens, Joseph R., "Lowbrow art : the unlikely defender of art history's tradition" (2013). LSU Master's Theses. 654. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOWBROW ART: THE UNLIKELY DEFENDER OF ART HISTORY’S TRADITION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Joseph R. Givens M.S., Arkansas State University, 2005 May 2013 I dedicate this work to my late twin brother Joshua Givens. Our shared love of comics, creative endeavors, and mischievous hijinks certainly influenced my love of Lowbrow Art. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professor Darius Spieth. Without his open mind and intellectual guidance, a thesis on this marginalized movement would not have been possible. I want to express my gratitude to Robert and Suzanne Williams who have patiently answered all of my inquiries without hesitation. -

Postcoloniality in the Art of Walton Ford Jaeun Ahn Wellesley College, [email protected]

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2012 The Return of Colonialism's Repressed: Postcoloniality in the Art of Walton Ford Jaeun Ahn Wellesley College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation Ahn, Jaeun, "The Return of Colonialism's Repressed: Postcoloniality in the Art of Walton Ford" (2012). Honors Thesis Collection. 15. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/15 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WELLESLEY COLLEGE THE RETURN OF COLONIALISM’S REPRESSED: POSTCOLONIALITY IN THE ART OF WALTON FORD A SENIOR THESIS SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR DEPARTMENTAL HONORS IN ART HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY JAEUN (CABELLE) AHN ADVISED BY DR. PATRICIA G. BERMAN WELLESLEY, MA MAY 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Jaeun (Cabelle) Ahn All rights reserved Reproduction prohibited without permission of the copyright owner. Acknowledgements: I would like first to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Patricia Berman, without whom this project would not have been possible. I am deeply grateful for her advice and support over the course of this project. Our stimulating discussions this past year have not only shaped my thesis but also my own professional development as a nascent academic. I am also grateful to the members of my thesis committee—Professor R. Bedell, Professor M. Carroll, Professor J. Oles, and Professor M. -

Walton Ford Aquarelle Bleibtreustraße 45, 10623 Berlin

Walton Ford Aquarelle Bleibtreustraße 45, 10623 Berlin 18 June – 14 August 2021 Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to announce Aquarelle, a solo exhibition of recent works by Walton Ford at Bleibtreustraße 45, Berlin. This is the artist’s frst solo presentation with the gallery. Ford is known for his monumental and extremely detailed watercolours depicting wild animals. His works expand upon the visual language and narrative scope of traditional natural history painting. Infuenced by historical sources such as the illustrations of John James Audubon (1785-1851), who gained popularity with his life-sized drawings of birds, the artist creates works of a unique luminosity in watercolour, gouache, and ink. Walton Ford, Detested, 2020, 152.4 x 212 cm.; 60 x 83 1/2 in. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging Drawing from a variety of sources, including scientifc illustrations, historical events, underground comics, literature, flms, and myths, he creates unique, surreal stories with a spark of black humour. “When I read a story that gives me an idea for a picture,” he explains, “I try to bring elements to the painting that are not contained in the text, so there’s a visual dimension to it you could never fnd elsewhere.” Ford’s masterfully precise way of working presents minutely detailed renderings of individual species and their behavioural patterns, and foregrounds the cultural-historical encounter between animals and humans as well. Many of the works on view at Galerie Max Hetzler powerfully refect on bizarre and often violent encounters between humans and wildlife, and their consequences. Although animals such as monkeys, felines, wolves, bears, and birds are undoubtedly the main protagonists in the artist's works, and human fgures rarely appear, their presence is always implied. -

Postcoloniality in the Art of Walton Ford a Senior Thesis

WELLESLEY COLLEGE THE RETURN OF COLONIALISM’S REPRESSED: POSTCOLONIALITY IN THE ART OF WALTON FORD A SENIOR THESIS SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR DEPARTMENTAL HONORS IN ART HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY JAEUN (CABELLE) AHN ADVISED BY DR. PATRICIA G. BERMAN WELLESLEY, MA MAY 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Jaeun (Cabelle) Ahn All rights reserved Reproduction prohibited without permission of the copyright owner. Acknowledgements: I would like first to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Patricia Berman, without whom this project would not have been possible. I am deeply grateful for her advice and support over the course of this project. Our stimulating discussions this past year have not only shaped my thesis but also my own professional development as a nascent academic. I am also grateful to the members of my thesis committee—Professor R. Bedell, Professor M. Carroll, Professor J. Oles, and Professor M. Viano—for their generous advice during this project and for their suggestions for its future. I would also like to acknowledge the following professors at Wellesley College: Professor W. Wood, Professor C. Dougherty, Professor K. Cassibry, Professor P. McGibbon, and Professor W. Rollman. Their probing questions and thoughtful suggestions have deeply impacted and shaped my thesis. I am indebted to Dr. Kristina Jones, the director of the Wellesley College Botanical Gardens, and to David Sommers, the assistant horticulturist at WCBG, for their patience with my embarrassing lack of botanical knowledge. I would also like to thank Brooke Henderson at the Wellesley College Art Library, for sharing her amazing research skills and for accommodating my most obscure and bizarre research requests.