Discovery of Nuclear Fission in Berlin 1938

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Tablets*

Memorial Tablets* Gregori Aminoff 1883-1947 Born 8 Feb. 1883 in Stockholm; died 11 Feb. 1947 in Stockholm. 1905 First academic degree, U. of Uppsala, after studying science in Stockholm. 1905 to about 19 13 studied painting in Florence and Italy. 1913 Returned to science. 1918 Ph.D. ; appointed Lecturer in Mineralogy and Crystallo- graphy U. of Stockholm. Thesis: Calcite and Barytes from Mzgsbanshiitten (Sweden). 1923-47 Professor and Head of the Department of Mineralogy of the Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. 1930 Married Birgit Broome, herself a crystallographer. see Nature (London) 1947, 159, 597 (G. Hagg). Dirk Coster 1889-1950 Born 5 Oct. 1889 in Amsterdam; died 12 Feb. 1950 in Groningen. Studied in Leiden, Delft, Lund (with Siegbahn) and Copenhagen (with Bohr). 1922 Dr.-ing. Tech. University of Delft. Thesis: X-ray Spectra and the Atomic Theory of Bohr. 1923 Assistant of H. A. Lorentz, Teyler Stichting in Haarlem. 1924-50 Prof. of Physics and Meteorology, U. of Groningen. Bergen Davis 1869-1951 Born 31 March 1869 in White House, New Jersey; died 1951 in New York. 1896 B.Sc. Rutgers University. 1900 A.M. Columbia University (New York). 1901 Ph.D. Columbia University. 1901-02 Postgraduate work in GMtingen. 1902-03 Postgraduate work in Cambridge. * The author (P.P.E.) is particularly aware of the incompleteness of this section and would be gratefid for being sent additional data. MEMORIAL TABLETS 369 1903 Instructor 1 1910 Assistant Professor Columbia University, New York. 1914 Associate Professor I 1918 Professor of Physics ] Work on ionization, radiation, electron impact, physics of X-rays, X-ray spectroscopy with first two-crystal spectrometer. -

Hitler and Heisenberg

The Wall Street Journal December 27-28, 2014 Book Review “Serving the Reich” by Philip Ball, Chicago, $30, 303 pages Hitler and Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg thought that once Germany had won, the ‘good Germans’ would get rid of the Nazis. Fizzing The museum inside the former basement tavern where in early 1945 German scientists built a small nuclear reactor. Associated Press by Jeremy Bernstein The German scientists who remained in Germany throughout the Nazi period can be divided into three main groups. At one end were the anti-Nazis—people who not only despised the regime but tried to do something about it. They were very few. Two that come to mind were Fritz Strassmann and Max von Laue. Strassmann was a radiochemist—a specialist in radioactive materials—who was blacklisted from university jobs by the Society of German Chemists in 1933 for his anti-Nazi views. He was fortunate to get a half-pay job at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, which got some of its funding from industry. He and his wife (they had a 3-year-old son) hid a Jewish friend in their apartment for months. With the radiochemist Otto Hahn, he performed the 1938 experiment in which fission was observed for the first time. Von Laue won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1914. Soon after Einstein published his 1905 paper on relativity, von Laue went to Switzerland to see him. They remained friends for life. Under the Nazis, Einstein’s work was denounced as “Jewish science.” When a number of von Laue’s colleagues agreed to use relativity but attribute it to some Aryan, he refused. -

The Transuranium Elements: from Neptunium and Plutonium to Element 112

UCRL-JC- 124728 The Transuranium Elements: From Neptunium and Plutonium to Element 112 Professor Darleane C. Hoffman Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory G. Seaborg Institute for Transactinium Science RECEIVED T. Isotope Sciences Division sEp23 ?9g6 This paper was prepared for submittal to the Conference Proceedings NATO Advanced Study Institute on "Actinides and the Environment" Chania, Crete, Greece July 7-19, 1996 July 26, 1996 DISCWMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor the University of California nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or the University of California, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best avaiiable original document. c THE TRANSURANIUM ELEMENTS: FROM NEPTUNIUM AM) PLUTONIUM TO ELEMENT112 DarIeane C. Hoffman Nuclear Science Division & Chemistry Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 & G. T. Seaborg Institute for ' Transactinium Science, MS-L23 1, LLNL, Livermore, CA 94550. -

Zirconium and Hafnium in 1998

ZIRCONIUM AND HAFNIUM By James B. Hedrick Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Imogene P. Bynum, statistical officer, and the world production table was prepared by Regina R. Coleman, international data coordinator. The principal economic source of zirconium is the zirconium withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data. silicate mineral, zircon (ZrSiO4). The mineral baddeleyite, a Domestic production of zircon increased as a new mine in natural form of zirconia (ZrO2), is secondary to zircon in its Virginia came online. Production of milled zircon was economic significance. Zircon is the primary source of all essentially unchanged from that of 1997. According to U.S. hafnium. Zirconium and hafnium are contained in zircon at a Customs trade statistics, the United States was a net importer of ratio of about 50 to 1. Zircon is a coproduct or byproduct of the zirconium ore and concentrates. In 1998, however, the United mining and processing of heavy-mineral sands for the titanium States was more import reliant than in 1997. Imports of minerals, ilmenite and rutile, or tin minerals. The major end zirconium ore and concentrates increased significantly as U.S. uses of zircon are refractories, foundry sands (including exports of zirconium ore and concentrates declined by 7%. investment casting), and ceramic opacification. Zircon is also With the exception of prices, all data in this report have been marketed as a natural gemstone, and its oxide processed to rounded to three significant digits. Totals and percentages produce the diamond simulant, cubic zirconia. Zirconium is were calculated from unrounded numbers. used in nuclear fuel cladding, chemical piping in corrosive environments, heat exchangers, and various specialty alloys. -

George De Hevesy in America

Journal of Nuclear Medicine, published on July 13, 2019 as doi:10.2967/jnumed.119.233254 George de Hevesy in America George de Hevesy was a Hungarian radiochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1943 for the discovery of the radiotracer principle (1). As the radiotracer principle is the foundation of all diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine procedures, Hevesy is widely considered the father of nuclear medicine (1). Although it is well-known that he spent time at a number of European institutions, it is not widely known that he also spent six weeks at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, in the fall of 1930 as that year’s Baker Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry (2-6). “[T]he Baker Lecturer gave two formal presentations per week, to a large and diverse audience and provided an informal seminar weekly for students and faculty members interested in the subject. The lecturer had an office in Baker Laboratory and was available to faculty and students for further discussion.” (7) There is also evidence that, “…Hevesy visited Harvard [University, Cambridge, MA] as a Baker Lecturer at Cornell in 1930…” (8). Neither of the authors of this Note/Letter was aware of Hevesy’s association with Cornell University despite our longstanding ties to Cornell until one of us (WCK) noticed the association in Hevesy’s biographical page on the official Nobel website (6). WCK obtained both his undergraduate degree and medical degree from Cornell in Ithaca and New York City, respectively, and spent his career in nuclear medicine. JRO did his nuclear medicine training at Columbia University and has subsequently been a faculty member of Weill Cornell Medical College for the last eleven years (with a brief tenure at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (affiliated with Cornell)), and is now the program director of the Nuclear Medicine residency and Chief of the Molecular Imaging and Therapeutics Section. -

Ian Rae: “Two Croatian Chemists Who Were Awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry”

Croatian Studies Review 13 (2017) Ian Rae: “Two Croatian Chemists who were Awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry” Ian Rae School of Chemistry University of Melbourne [email protected] Abstract Two organic chemists of Croatian origin, Leopold Ružička and Vladimir Prelog, made significant contributions to natural product chemistry during the twentieth century. They received their university education and research training in Germany and Czechoslovakia, respectively. Both made their careers in Zürich, Switzerland, and both shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, in 1939 and 1975, respectively. In this article, I have set the details of their lives and achievements against the education and research climates in Europe and other regions, especially as they apply to the field of chemistry. Key words: Croatia, organic, chemistry, Nobel, Ružička, Prelog 31 Croatian Studies Review 13 (2017) Introduction1 In the twentieth century two organic chemists of Croatian origin were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. They were Lavoslav (Leopold) Ružička (1887-1976) and Vladimir Prelog (1906-1998), whose awards came in 1939 and 1975, respectively. Both were living and working in Switzerland at the time of the awards and it was in that country – specifically in the city of Zürich – that they performed the research that made them Nobel Laureates. To understand the careers of Ružička and Prelog, and of many other twentieth century organic chemists, we need to look back to the nineteenth century when German chemists were the leaders in this field of science. Two developments characterise this German hegemony: the introduction of the research degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), and the close collaboration between organic chemists in industry and university. -

Pauling-Linus.Pdf

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES L I N U S C A R L P A U L I N G 1901—1994 A Biographical Memoir by J A C K D. D UNITZ Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1997 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. LINUS CARL PAULING February 28, 1901–August 19, 1994 BY JACK D. DUNITZ INUS CARL PAULING was born in Portland, Oregon, on LFebruary 28, 1901, and died at his ranch at Big Sur, California, on August 19, 1994. In 1922 he married Ava Helen Miller (died 1981), who bore him four children: Linus Carl, Peter Jeffress, Linda Helen (Kamb), and Edward Crellin. Pauling is widely considered the greatest chemist of this century. Most scientists create a niche for themselves, an area where they feel secure, but Pauling had an enormously wide range of scientific interests: quantum mechanics, crys- tallography, mineralogy, structural chemistry, anesthesia, immunology, medicine, evolution. In all these fields and especially in the border regions between them, he saw where the problems lay, and, backed by his speedy assimilation of the essential facts and by his prodigious memory, he made distinctive and decisive contributions. He is best known, perhaps, for his insights into chemical bonding, for the discovery of the principal elements of protein secondary structure, the alpha-helix and the beta-sheet, and for the first identification of a molecular disease (sickle-cell ane- mia), but there are a multitude of other important contri- This biographical memoir was prepared for publication by both The Royal Society of London and the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. -

CARL BOSCH and HIS MUSEUM Fathi Habashi, Laval University

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 35, Number 2 (2010) 111 CARL BOSCH AND HIS MUSEUM Fathi Habashi, Laval University Carl Bosch (1874-1940) (Fig. 1) was for the development of the catalysts. born in Cologne, studied metallurgy Further problems which had to be and mechanical engineering at the Tech- solved were the construction of safe nische Hochschule in Berlin (1894-96), high-pressurized reactors and a cheap then chemistry at Leipzig University, way of producing and cleaning the graduating in 1898. In 1899 he entered gases necessary for the synthesis of the employ of the Badische Anilin- und ammonia. Step by step Bosch went Sodafabrik in Ludwigshafen (Fig. 2) on to using increasingly larger manu- and participated in the development facturing units. In order to solve the of the then new industry of synthetic growing problems posed by materials indigo. and related safety problems, BASF set up the chemical industry’s first When in 1908 the Badische ac- Materials Testing Laboratory in 1912 quired the process of high-pressure to identify and control problems in synthesis of ammonia, which had been materials for instrumentation and developed by Fritz Haber (1868-1934) process engineering. at the Technische Hochschule in Karl- sruhe, Bosch was given the task of The plant in Oppau for the pro- developing this process on an industrial duction of ammonia and nitrogen Figure 1. Carl Bosch (1874-1940) scale. This involved the construction of fertilizers was opened in 1913. Bosch plant and apparatus which would stand up wanted fertilizers to be tested thorough- to working at high gas pressure and high-reaction tem- ly, so that customers were to be given proper instructions peratures. -

April 17-19, 2018 the 2018 Franklin Institute Laureates the 2018 Franklin Institute AWARDS CONVOCATION APRIL 17–19, 2018

april 17-19, 2018 The 2018 Franklin Institute Laureates The 2018 Franklin Institute AWARDS CONVOCATION APRIL 17–19, 2018 Welcome to The Franklin Institute Awards, the a range of disciplines. The week culminates in a grand United States’ oldest comprehensive science and medaling ceremony, befitting the distinction of this technology awards program. Each year, the Institute historic awards program. celebrates extraordinary people who are shaping our In this convocation book, you will find a schedule of world through their groundbreaking achievements these events and biographies of our 2018 laureates. in science, engineering, and business. They stand as We invite you to read about each one and to attend modern-day exemplars of our namesake, Benjamin the events to learn even more. Unless noted otherwise, Franklin, whose impact as a statesman, scientist, all events are free, open to the public, and located in inventor, and humanitarian remains unmatched Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. in American history. Along with our laureates, we celebrate his legacy, which has fueled the Institute’s We hope this year’s remarkable class of laureates mission since its inception in 1824. sparks your curiosity as much as they have ours. We look forward to seeing you during The Franklin From sparking a gene editing revolution to saving Institute Awards Week. a technology giant, from making strides toward a unified theory to discovering the flow in everything, from finding clues to climate change deep in our forests to seeing the future in a terahertz wave, and from enabling us to unplug to connecting us with the III world, this year’s Franklin Institute laureates personify the trailblazing spirit so crucial to our future with its many challenges and opportunities. -

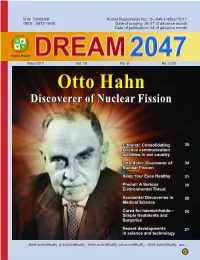

Otto Hahn Otto Hahn

R.N. 70269/98 Postal Registration No.: DL-SW-1/4082/15-17 ISSN : 0972-169X Date of posting: 26-27 of advance month Date of publication: 24 of advance month May 2017 Vol. 19 No. 8 Rs. 5.00 Otto Hahn Discoverer of Nuclear Fission Editorial: Consolidating 35 science communication activities in our country Otto Hahn: Discoverer of 34 Nuclear Fission Keep Your Eyes Healthy 31 Phenol: A Serious 30 Environmental Threat Accidental Discoveries in 28 Medical Science Cures for haemorrhoids— 24 Simple treatments and Surgeries Recent developments 21 in science and technology 36 Editorial Consolidating science communication activities in our country Dr. R. Gopichandran It is well known that the National Council of Science Museums of India’s leadership in science technology and innovation (STI) across the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, the National Institute the bilateral and multilateral framework also. The news feature service of Science Communication and Information Resources (NISCAIR) and the portal activity have well defined action plans to reach out to of CSIR, the National Council for Science and Technology fellow institutions and citizens with suitably embellished platform Communication (NCSTC) of the Department of Science and and opportunities for all to deliver together. Technology (DST), Government of India and Vigyan Prasar, also While these are interesting and extremely important, especially of DST, have been carrying out excellent science communication because they respond to the call to upscale and value add science activities over the years. It cannot be denied that the reach has been and technology communication, it is equally important to document quite significant collectively. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

Milestones and Personalities in Science and Technology

History of Science Stories and anecdotes about famous – and not-so-famous – milestones and personalities in science and technology BUILDING BETTER SCIENCE AGILENT AND YOU For teaching purpose only December 19, 2016 © Agilent Technologies, Inc. 2016 1 Agilent Technologies is committed to the educational community and is willing to provide access to company-owned material contained herein. This slide set is created by Agilent Technologies. The usage of the slides is limited to teaching purpose only. These materials and the information contained herein are accepted “as is” and Agilent makes no representations or warranties of any kind with respect to the materials and disclaims any responsibility for them as may be used or reproduced by you. Agilent will not be liable for any damages resulting from or in connection with your use, copying or disclosure of the materials contained herein. You agree to indemnify and hold Agilent harmless for any claims incurred by Agilent as a result of your use or reproduction of these materials. In case pictures, sketches or drawings should be used for any other purpose please contact Agilent Technologies a priori. For teaching purpose only December 19, 2016 © Agilent Technologies, Inc. 2016 2 Table of Contents The Father of Modern Chemistry The Man Who Discovered Vitamin C Tags: Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, chemical nomenclature Tags: Albert Szent-Györgyi, L-ascorbic acid He Discovered an Entire Area of the Periodic Table The Discovery of Insulin Tags: Sir William Ramsay, noble gas Tags: Frederick Banting,