Type of Paper: Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2013 Nr

946.223.3 Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2013 Nr. 143 ausgegeben am 25. März 2013 Verordnung vom 20. März 2013 betreffend die Abänderung der Verordnung über Massnahmen gegenüber der Islamischen Republik Iran Aufgrund von Art. 2 des Gesetzes vom 10. Dezember 2008 über die Durchsetzung internationaler Sanktionen (ISG), LGBl. 2009 Nr. 41, unter Einbezug der aufgrund des Zollvertrages anwendbaren schweizeri- schen Rechtsvorschriften und der Beschlüsse des Rates der Europäischen Union vom 26. Juli 2010 (2010/413/GASP), vom 12. April 2011 (2011/235/GASP), vom 23. Mai 2011 (2011/299/GASP), vom 10. Oktober 2011 (2011/670/GASP), vom 1. Dezember 2011 (2011/783/GASP), vom 23. Januar 2012 (2012/35/GASP), vom 15. März 2012 (2012/152/GASP), vom 23. März 2012 (2012/168/GASP), vom 23. April 2012 (2012/205/GASP), vom 2. August 2012 (2012/457/GASP), vom 15. Oktober 2012 (2012/635/GASP), vom 21. Dezember 2012 (2012/829/GASP) und vom 11. März 2013 (2013/124/GASP) sowie in Ausführung der Resolutionen 1737 (2006) vom 23. Dezember 2006, 1747 (2007) vom 24. März 2007, 1803 (2008) vom 3. März 2008 und 1929 (2010) vom 9. Juni 2010 des Si- cherheitsrates der Vereinten Nationen verordnet die Regierung: I. Abänderung bisherigen Rechts Die Verordnung vom 1. Februar 2011 über Massnahmen gegenüber der Islamischen Republik Iran, LGBl. 2011 Nr. 55, in der geltenden Fas- sung, wird wie folgt abgeändert: 2 Anhang 6 Bst. A Überschrift vor Ziff. 1, Überschrift nach Ziff. 326 sowie Ziff. 1 A. Unternehmen und Organisationen a) Beschluss 2010/413/GASP … b) Beschluss 2011/235/GASP Name Identifizierungsinformation 1. -

Asia 21 Press Release FINAL3

News Public Relations Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 www.AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Fax 212.517.8315 E-mail [email protected] ASIA SOCIETY ANNOUNCES 2010-2011 FELLOWS CLASS OF ASIA 21 YOUNG LEADERS 19 Fellows selected representing 16 countries New York, January 27, 2010 – The Asia Society today announced the names of its 2010-2011 Class of Asia Society Asia 21 Fellows, a total of 19 next generation leaders from 16 countries in the Asia Pacific region. The Asia 21 Young Leaders Initiative, established by the Asia Society with support from Founding International Sponsor Bank of America Merrill Lynch, is the pre- eminent leadership development program in the Asia-Pacific region for emerging leaders under the age of 40. Representing a broad range of sectors, the Fellows will come together three times during their Fellowship year to address topics relating to environmental degradation, economic development, poverty eradication, universal education, conflict resolution, HIV/AIDS and public health crises, human rights, and other issues. They will meet twice at the Asia 21 Young Leaders Forum, and once at the Asia 21 Young Leaders Summit, set to be held in late 2010. The first meeting of the 2010-2011 Class will be held in Florida from February 28 to March 3, 2010 where they will participate in a series of meetings designed to generate creative, shared approaches to leadership and problem solving and develop collaborative public service projects. The Class includes an Iranian journalist and filmmaker whose detention after last year’s Iranian elections led to a major international campaign for his release, one of the leading environmental lawyers in China, and an astronaut trainer. -

Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’S Proliferation Strategy

Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’s Proliferation Strategy Michael Eisenstadt and Mehdi Khalaji Policy Focus #115 | September 2011 Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’s Proliferation Strategy Michael Eisenstadt and Mehdi Khalaji Policy Focus #115 | September 2011 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei delivering a speech on November 8, 2006, where he stated that his country would continue to acquire nuclear technology and challenge “Western fabrications.” (AP Photo/ISNA, Morteza Farajabadi) Contents About the Authors. v Preface. vii Executive Sumary . ix 1. Religious Ideologies, Political Doctrines, and Nuclear Decisionmaking . 1 Michael Eisenstadt 2. Shiite Jurisprudence, Political Expediency, and Nuclear Weapons. 13 Mehdi Khalaji About the Authors Michael Eisenstadt is director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. A spe- cialist in Persian Gulf and Arab-Israeli security affairs, he has published widely -

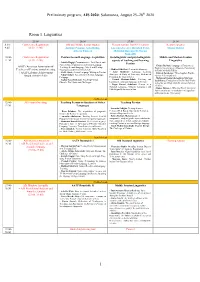

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Event Archives August 2014 - July 2015 Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations

Event Archives August 2014 - July 2015 Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations Events at Duke, Events at UNC, Events in the Triangle Tues, Aug 19 – Fri, Visual Reactions: A View from the Middle East Oct 31, 2014 Time: August 19, 2014 - October 31, 2014, building hours weekdays 7:30am-9:00pm Location: FedEx Global Education Center UNC Chapel Hill Categories: Art, Exhibit Description: “Visual Reactions: A View from the Middle East” features more than 20 illustrations by Kuwaiti artist and graphic designer Mohammad Sharaf. Inspired by current events, Sharaf’s designs address controversial political and social topics. Sharaf’s illustrations will be on display in the UNC FedEx Global Education Center from Aug. 19 to Oct. 31. The exhibition touches on topics ranging from women’s rights to the multiple iterations of the Arab spring in the Middle East. Sharaf’s work also portrays current events, such as Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to allow women to drive motorcycles and bicycles as long as a male guardian accompanies them. A free public reception and art viewing will be held on Aug. 28 from 5:30 to 8 p.m. at the UNC FedEx Global Education Center. Sponsors: Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations, the Center for Global Initiatives, the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies and Global Relations with support from the Department of Asian Studies. Special thanks to Andy Berner, communications specialist for the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Program Thurs, -

Incitement: Antisemitism and Violence in Iran’S Current State Textbooks

A report from ADL International Affairs FEB 2021 Incitement: Antisemitism and Violence in Iran’s Current State Textbooks (top) Image titled “Let’s Go” from a current Iranian state textbook depicting an IRGC officer killed in Syria named Mohsen Hojaji. Grade 10, Defense Preparation, page 123 (bottom) Image from a current Iranian state textbook, in a lesson titled “Cultural Attack”. Grade 9, Heaven’s Messages: Islamic Education and Training, p. 105 Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment to all. ADL INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ADL’s International Affairs (IA) pursues ADL’s mission around the globe, fighting antisemitism and hate, supporting the security of Jewish communities worldwide and working for a safe, democratic and pluralistic State of Israel at peace with her neighbors. ADL places a special emphasis on Europe, Latin America and Israel, but advocates for many Jewish communities around the world facing antisemitism. With a full-time staff in Israel, IA promotes social cohesion in Israel as a means of strengthening the Jewish and democratic character of the State, while opposing efforts to delegitimize it. The IA staff helps raise these international issues with the U.S. and foreign ABOUT THE AUTHOR governments and works with partners around the world to provide research and David Andrew Weinberg is analysis, programs and resources to fight antisemitism, extremism, hate crimes ADL’s Washington Director for and cyberhate. With a seasoned staff of international affairs experts, ADL’s IA International Affairs. He also division is one of the world’s foremost authorities in combatting all forms of serves as the organization’s hate globally. -

Council Decision (Cfsp) 2021/595

L 125/58 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 13.4.2021 COUNCIL DECISION (CFSP) 2021/595 of 12 April 2021 amending Decision 2011/235/CFSP concerning restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities in view of the situation in Iran THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in particular Article 29 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 12 April 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/235/CFSP (1). (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/235/CFSP, the Council considers that the restrictive measures set out therein should be renewed until 13 April 2022. (3) One person designated in the Annex to Decision 2011/235/CFSP is deceased, and his entry should be removed from that Annex. The Council has also concluded that the entries concerning 34 persons and one entity included in the Annex to Decision 2011/235/CFSP should be updated. (4) Decision 2011/235/CFSP should therefore be amended accordingly, HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: Article 1 Decision 2011/235/CFSP is amended as follows: (1) in Article 6, paragraph 2 is replaced by the following: ‘2. This Decision shall apply until 13 April 2022. It shall be kept under constant review. It shall be renewed, or amended as appropriate, if the Council deems that its objectives have not been met.’; (2) the Annex is amended as set out in the Annex to this Decision. Article 2 This Decision shall enter into force on the date of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. -

MDE 130622010 from Protest to Prison WITHOUT PICTURE

FROM PROTEST TO PRISON IRAN ONE YEAR AFTER THE ELECTION Amnesty International Publications First published in 2010 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2008 Index: MDE 13/062/2010 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................5 2. Who are the prisoners? ..............................................................................................9 Political activists .....................................................................................................10 -

The Current Volume 23

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 10-16-2012 The urC rent Volume 23 : Issue 9 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The urC rent Volume 23 : Issue 9" (2012). The Current. 372. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/372 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , . .. .. , . • • •• . nsucurrent.nova.edu Coach's Page 6 fJoge '5 NSU plays host to . senatori debate Jt~ .: .S~y. .R~~,:ir() .... ... .... On Oct.17, NSU will host a live televised debate in the race for United States Senator from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. in the Rose and Alfred Miniaci Performing Arts Center. ''Decision 2012: Before You VOle". a project created by Leadership Florida in pannership with the Florida Press Association, is pairing up with NSU to host the general election debate between Democratic candidate, incumbent U.S. Senator Bill Nelson and Republican candidate. U.S. Representative Connie Mack. This is not the first time NSU has been chosen as an arena for politics. In both 2006 and 2010, the university hosted the debate in the state race for U.S. senator. Brandon Hensler, assistant COURTESY OF NEVERAGAINPHOTOGRAPHY.BIZ SEE DEBATE 2 COURTESY OF LAnMES.COM Democratic candidate, incumbenl U.S Senator, BUI Nelsoo. Republican candidate, U.s, Representative Connie Mack. Iran prison survivor to visit NSU On Oct. -

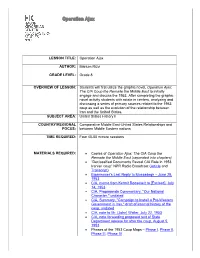

Operation Ajax

Operation Ajax LESSON TITLE: Operation Ajax AUTHOR: Marium Rizvi GRADE LEVEL: Grade 8 OVERVIEW OF LESSON: Students will first utilize the graphic novel, Operation Ajax: The CIA Coup the Remade the Middle East to initially engage and discuss the 1953. After completing the graphic novel activity students with rotate in centers, analyzing and discussing a series of primary sources related to the 1953 coup as well as the evolution of the relationship between Iran and the United States. SUBJECT AREA: United States History II COUNTRY/REGIONAL Comparative Middle East-United States Relationships and FOCUS: between Middle Eastern nations TIME REQUIRED: Four 45-55 minute sessions MATERIALS REQUIRED: • Copies of Operation Ajax: The CIA Coup the Remade the Middle East (separated into chapters) • “Declassified Documents Reveal CIA Role in 1953 Iranian coup” NPR Radio Broadcast (Article and Transcript) • Eisenhower’s Last Reply to Mossadegh – June 29, 1953 • CIA, memo from Kermit Roosevelt to [Excised], July 14, 1953 • CIA, Propaganda Commentary, "Our National Character," undated • CIA, Summary, "Campaign to Install a Pro-Western Government in Iran," draft of internal history of the coup, undated • CIA, note to Mr. [John] Waller, July 22, 1953 • CIA, note forwarding proposed text of State Department release for after the coup, August 5, 1953 • Phases of the 1953 Coup Maps – Phase I, Phase II, Phase III, Phase IV Operation Ajax • Iranian Parliament Passes Bill To Sue Washington Over 1953 Coup • Iran seeks money from U.S. over 1953 coup that empowered American-backed shah • Can Iran sue the US for Coup & supporting Saddam in Iran-Iraq War? • Iran MPs want US to pay for damage inflicted since 1953 (PressTV clip) • CIA, Memo, "Proposed Commendation for Communications Personnel who have serviced the TPAJAX Operation," Frank G. -

Download the Transcript

IRAN-2018/01/05 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM THE PROTESTS IN IRAN Washington, D.C. Friday, January 5, 2018 Introduction: NATAN SACHS Fellow and Director, Center for Middle East Policy The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: MAZIAR BAHARI Founder, IranWire Author, Then They Came for Me Discussant: SUZANNE MALONEY Senior Fellow and Deputy Director, Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution Moderator: SUSAN GLASSER Chief International Affairs Columnist Politico * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 IRAN-2018/01/05 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. SACHS: Good morning everyone. Thank you for braving the aftermath of the cyclone bomb and the polar vortex, and other linguistic innovations. And welcome on behalf of Brookings and the Center for Middle East Policy. My name is Natan Sachs; I'm the Director of the Center for Middle East Policy. And, again, welcome to everyone here in the room, everyone joining us on our webcast on the Brookings website, and everyone joining via C-SPAN at home. We have an extremely important topic this morning and an excellent panel to discuss it. We often have debates on Middle East policy on interests and what the U.S. should do in terms of immediate policy and pursuing its interests. We often have debates about what the U.S. should do in terms of its values, promoting its vision of the good life, its vision of what the world should look like. And once in a while we have an issue that very clearly encapsulates both, and this is one of them. -

Workers Committees Spread Throughout Country ·Iranian Soldier Appeals to American Gls • SAVAK Killer Admits C La Complici

DECEMBER 28, 1979 50 CENTS VOLUME 43/NUMBER 50 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Banner on occupied U.S. Embassy. Millions of Iranians dentify y w th strugg es o etnamese, ans, and Nicaraguans against exploitation and domination by Washington. For firsthand reports from 'Militant' editor Cindy Jaquith in Tehran, see pages 5-9. Exclusive reports from Tehran: ·Workers committees spread throughout country ·Iranian soldier appeals to American G.l.s • SAVAK killer admits ClA complicity Sleet In Our Opinion VOLUME 43/NUMBER 50 DECEMBER 28, 1979 CLOSING NEWS DATE-DEC. 19 That is why students in the embassy and Carter shifts shah to Panama, millions of other Iranians insist on a trial or international tribunal in which some of the embassy personnel might figure as defendants escalates war threats against Iran or witnesses. (At the same time, they stress The following statement was issued bloody criminal. The demand for the extradi that the hostages will be released when the December 19 by Socialist Workers Party tion of the shah to Iran is gaining support. shah is returned, regardless of the outcome of presidential candidate Andrew Pulley. Carter hopes moving the shah will make the the hearings). American people stop thinking about and They want to expose the crimes of the shah, Carter is again trying to escalate the conflict discussing the mass murderer and his record. and the U.S. government's role in imposing with Iran. This maneuver is also an insult to the his tyranny on Iran-organizing and supply He has threatened a naval blockade or other Panamanian people.