Changes in the Wild Bee Fauna of Rockefeller Prairie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NENHC 2013 Oral Presentation Abstracts

Oral Presentation Abstracts Listed alphabetically by presenting author. Presenting author names appear in bold. Code following abstract refers to session presentation was given in (Day [Sun = Sunday, Mon = Monday] – Time slot [AM1 = early morning session, AM2 = late morning session, PM1 = early afternoon session, PM2 = late afternoon session] – Room – Presentation sequence. For example, Mon-PM1-B-3 indicates: Monday early afternoon session in room B, and presentation was the third in sequence of presentations for that session. Using that information and the overview of sessions chart below, one can see that it was part of the “Species-Specific Management of Invasives” session. Presenters’ contact information is provided in a separate list at the end of this document. Overview of Oral Presentation Sessions SUNDAY MORNING SUNDAY APRIL 14, 2013 8:30–10:00 Concurrent Sessions - Morning I Room A Room B Room C Room D Cooperative Regional (Multi- Conservation: state) In-situ Breeding Ecology of Ant Ecology I Working Together to Reptile/Amphibian Songbirds Reintroduce and Conservation Establish Species 10:45– Concurrent Sessions - Morning II 12:40 Room A Room B Room C Room D Hemlock Woolly Bird Migration and Adelgid and New Marine Ecology Urban Ecology Ecology England Forests 2:00–3:52 Concurrent Sessions - Afternoon I Room A Room B Room C Room D A Cooperative Effort to Identify and Impacts on Natural History and Use of Telemetry for Report Newly Biodiversity of Trends in Northern Study of Aquatic Emerging Invasive Hydraulic Fracturing Animals -

Thesis (6.864Mb)

NAVIGATING NUANCE IN NATIVE BEE RESPONSES TO GRASSLAND RESTORATION MANAGEMENT: A MULTI-ECOREGIONAL APPROACH IN THE GREAT PLAINS A Thesis by Alex Morphew Bachelor of Arts, University of Colorado, 2017 Submitted to the Department of Biological Sciences and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science December 2019 © Copyright 2019 by Alex Morphew All Rights Reserved NAVIGATING NUANCE IN NATIVE BEE RESPONSES TO GRASSLAND RESTORATION MANAGEMENT: A MULTI-ECOREGIONAL APPROACH IN THE GREAT PLAINS The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science with a major in Biological Sciences. Mary Jameson, Committee Chair Gregory Houseman, Committee Member Doug English, Committee Member iii “The idea of wilderness needs no defense, it just needs defenders.”—Edward Abbey “The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem it will avail us little to solve all others.”—Theodore Roosevelt iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research would not have been possible, by any stretCh of the imagination, without the immense number of people who played many integral roles along the way. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mary Liz Jameson; your willingness to adventure into the world of native bee eCology and your unwavering support gave me the motivation and Confidence I needed to be the sCientist I am today. Your enthusiasm for research and Conservation, your constant generosity and kindness, and your dediCation to your students is unparalleled, and I am beyond fortunate to have had the opportunity to work so closely with you. -

Land Uses That Support Wild Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Communities Within an Agricultural Matrix

Land uses that support wild bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) communities within an agricultural matrix A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elaine Celeste Evans IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Marla Spivak December 2016 © Elaine Evans 2016 Acknowledgements Many people helped me successfully complete this project. Many years ago, my advisor, mentor, hero, and friend, Marla Spivak, saw potential in me and helped me to become an effective scientist and educator working to create a more bee-friendly world. I have benefitted immensely from her guidance and support. The Bee Lab team, both those that helped me directly in the field, and those that advised along the way through analysis and writing, have provided a dreamy workplace: Joel Gardner, Matt Smart, Renata Borba, Katie Lee, Gary Reuter, Becky Masterman, Judy Wu, Ian Lane, Morgan Carr- Markell. My committee helped guide me along the way and steer me in the right direction: Dan Cariveau (gold star for much advice on analysis), Diane Larson, Ralph Holzenthal, and Karen Oberauser. Cooperation with Chip Eullis and Jordan Neau at the USGS enabled detailed land use analysis. The bee taxonomists who helped me with bee identification were essential for the success of this project: Jason Gibbs, John Ascher, Sam Droege, Mike Arduser, and Karen Wright. My friends and family eased my burden with their enthusiasm for me to follow my passion and their understanding of my monomania. My husband Paul Metzger and my son August supported me in uncountable ways. -

Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Habitat in Agroecosystems Morgan Mackert Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems Morgan Mackert Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Mackert, Morgan, "Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17255. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17255 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems by Morgan Marie Mackert A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Program of Study Committee: Mary A. Harris, Co-major Professor John D. Nason, Co-major Professor Robert W. Klaver The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2019 Copyright © Morgan Marie Mackert, 2019. All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Butterflies of North America

Insects of Western North America 7. Survey of Selected Arthropod Taxa of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma. 4. Hexapoda: Selected Coleoptera and Diptera with cumulative list of Arthropoda and additional taxa Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1177 2 Insects of Western North America. 7. Survey of Selected Arthropod Taxa of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma. 4. Hexapoda: Selected Coleoptera and Diptera with cumulative list of Arthropoda and additional taxa by Boris C. Kondratieff, Luke Myers, and Whitney S. Cranshaw C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 August 22, 2011 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity. Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1177 3 Cover Photo Credits: Whitney S. Cranshaw. Females of the blow fly Cochliomyia macellaria (Fab.) laying eggs on an animal carcass on Fort Sill, Oklahoma. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, 80523-1177. Copyrighted 2011 4 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................7 SUMMARY AND MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS -

An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes)

An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming BY David J. Drons A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Plant Science South Dakota State University 2012 ii An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming This thesis is approved as a credible and independent investigation by a candidate for the Master of Plant Science degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. __________________________________ Dr. Paul J. Johnson Thesis Advisor Date __________________________________ Dr. Doug Malo Assistant Plant Date Science Department Head iii Acknowledgements I (the author) would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Paul J. Johnson and my committee members Dr. Carter Johnson and Dr. Alyssa Gallant for their guidance. I would also like to thank the South Dakota Game Fish and Parks department for funding this important project through the State Wildlife Grants program (grant #T2-6-R-1, Study #2447), and Custer State Park assisting with housing during the field seasons. A special thank you to taxonomists who helped with bee identifications: Dr. Terry Griswold, Jonathan Koch, and others from the USDA Logan bee lab; Karen Witherhill of the Sivelletta lab at the University of New Mexico; Dr. Laurence Packer, Shelia Dumesh, and Nicholai de Silva from York University; Rita Velez from South Dakota State University, and Jelle Devalez a visiting scientist at the US Geological Survey. -

Zootaxa, a Review of the Cleptoparasitic Bee Genus Triepeolus

ZOOTAXA 1710 A review of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Triepeolus (Hymenoptera: Apidae).—Part I MOLLY G. RIGHTMYER Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand MOLLY G. RIGHTMYER A review of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Triepeolus (Hymenoptera: Apidae).—Part I (Zootaxa 1710) 170 pp.; 30 cm. 22 Feb. 2008 ISBN 978-1-86977-191-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-192-8 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2008 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2008 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 1710 © 2008 Magnolia Press RIGHTMYER Zootaxa 1710: 1–170 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A review of the cleptoparasitic bee genus Triepeolus (Hymenoptera: Apidae).— Part I MOLLY G. RIGHTMYER Department of Entomology, MRC 188, P. O. Box 37012, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 USA [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . .5 Introduction . .6 Materials and methods . .7 Morphology . .9 Key to the females of North and Central America . -

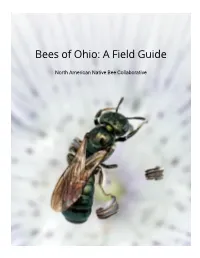

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

Community Patterns and Plant Attractiveness to Pollinators in the Texas High Plains

Scale-Dependent Bee (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) Community Patterns and Plant Attractiveness to Pollinators in the Texas High Plains by Samuel Discua, B.Sc., M.Sc. A Dissertation In Plant and Soil Science Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Scott Longing Chair of the Committee Nancy McIntyre Robin Verble Cynthia McKenney Joseph Young Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Samuel Discua Texas Tech University, Samuel Discua, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many who helped me along the way on this long and difficult journey. I want to take a moment to thank them. First, I wish to thank my dissertation committee. Without their guidance, I would not have made it. Dr. McIntytre, Dr. McKenney, Dr. Young and Dr. Verble served as wise committee members, and Dr. Longing, my committee chair, for sticking with me and helping me reach my goal. To the Longing Lab members, Roberto Miranda, Wilber Gutierrez, Torie Wisenant, Shelby Chandler, Bryan Guevara, Bianca Rendon, Christopher Jewett, thank you for all the hard work. To my family, my parents, my sisters, and Balentina and Bruno: you put up with me being distracted and missing many events. Finally, and most important, to my wife, Baleshka, your love and understanding helped me through the most difficult times. Without you believing in me, I never would have made it. It is time to celebrate; you earned this degree right along with me. I am forever grateful for your patience and understanding. -

Fire, Grazing, and Other Drivers of Bee Communities in Remnant Tallgrass Prairie

The Revery Alone Won’t Do: Fire, Grazing, and Other Drivers of Bee Communities in Remnant Tallgrass Prairie A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Patrick Pennarola IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Ralph Holzenthal, adviser April 2019 © Patrick Pennarola, 2019 Acknowledgement: This research was conducted on the colonized homelands of the Anishinaabe, Dakota, and Lakota peoples, who are still here. i Dedication To Anya, for who you are To my child, for whoever you become To Nora, for the courage to see it through ii Table of contents Acknowledgement . .. i Dedication . .. ii List of Tables . .. iv List of Figures . .. v Introduction . .. 1 Bees in decline . .. .1 Tallgrass prairie in Minnesota. .. 5 Bees’ response to management. .. 9 Conclusion . .. .12 Chapter 1: The role of fire and grazing in driving patterns of bee abundance, species richness, and diversity . .. 13 Synopsis. .13 Introduction . .13 Methods . .18 Results. 26 Discussion. 28 Chapter 2: The trait-based responses of bee communities to environmental drivers of tallgrass prairie . .. .51 Synopsis. .51 Introduction . .52 Methods . .57 Results. 68 Discussion. 70 Bibliography . .. 81 Appendix A: Table of species collected . .82 Appendix B: Table of species by traits . .96 iii List of Tables Table 1: Parameters for all linear and generalized-linear mixed-effects models built. 37 Table 2: Wald’s Test χ2 values for terms in generalized linear model of adjusted bee abundance . .38 Table 3: Wald’s Test χ2 values for terms in generalized linear model of Chao 2 estimated species richness . .39 Table 4: F-test values for terms in linear model of Shannon’s H diversity index . -

The Maryland Entomologist

THE MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST Insect and related-arthropod studies in the Mid-Atlantic region Volume 6, Number 1 September 2013 September 2013 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 6, Number 1 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY Executive Committee: President Frederick Paras Vice President Philip J. Kean Secretary Richard H. Smith, Jr. Treasurer Edgar A. Cohen, Jr. Historian Robert S. Bryant Publications Editor Eugene J. Scarpulla The Maryland Entomological Society (MES) was founded in November 1971, to promote the science of entomology in all its sub-disciplines; to provide a common meeting venue for professional and amateur entomologists residing in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and nearby areas; to issue a periodical and other publications dealing with entomology; and to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information through its meetings and publications. The MES was incorporated in April 1982 and is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, scientific organization. The MES logo features an illustration of Euphydryas phaëton (Drury), the Baltimore Checkerspot, with its generic name above and its specific epithet below (both in capital letters), all on a pale green field; all these are within a yellow ring double-bordered by red, bearing the message “● Maryland Entomological Society ● 1971 ●”. All of this is positioned above the Shield of the State of Maryland. In 1973, the Baltimore Checkerspot was named the official insect of the State of Maryland through the efforts of many MES members. Membership in the MES is open to all persons interested in the study of entomology. All members receive the annual journal, The Maryland Entomologist, and the monthly e-newsletter, Phaëton. Institutions may subscribe to The Maryland Entomologist but may not become members. -

(Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of St. Louis, Missouri, USA Author(S): Gerardo R

A Checklist of the Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of St. Louis, Missouri, USA Author(s): Gerardo R. Camilo, Paige A. Muñiz, Michael S. Arduser, and Edward M. Spevak Source: Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 90(3):175-188. Published By: Kansas Entomological Society https://doi.org/10.2317/0022-8567-90.3.175 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2317/0022-8567-90.3.175 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. JOURNAL OF THE KANSAS ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 90(3), 2017, pp. 175–188 A Checklist of the Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of St. Louis, Missouri, USA GERARDO R. CAMILO,1,*PAIGE A. MUNIZ˜ ,1 MICHAEL S. ARDUSER,2 AND EDWARD M. SPEVAK3 ABSTRACT: Concern over the declines of pollinator populations during the last decade has resulted in calls from governments and international agencies to better monitor these organisms.