Melisma Inside Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and Their Use for Composition

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and their Use for Composition submitted by Georg Boenn for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Bath Department of Computer Science February 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author. This thesis may not be consulted, photocopied or lent to other libraries without the permission of the author for 3 years from the date of acceptance of the thesis. Signature of Author . .................................. Georg Boenn To Daiva, the love of my life. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Musical Time and the Problem of Musical Form . 17 1.2 Context of Research and Research Questions . 18 1.3 Previous Publications . 24 1.4 Contributions..................................... 25 1.5 Outline of the Thesis . 27 2 Background and Related Work 28 2.1 Introduction...................................... 28 2.2 Representations of Musical Rhythm . 29 2.2.1 Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 29 2.2.2 The Piano-Roll Notation . 33 2.2.3 Necklace Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 34 2.2.4 Adjacent Interval Spectrum . 36 2.3 Onset Detection . 36 2.3.1 ManualTapping ............................... 36 The times Opcode in Csound . 38 2.3.2 MIDI ..................................... 38 MIDIFiles .................................. 38 MIDIinReal-Time.............................. 40 2.3.3 Onset Data extracted from Audio Signals . 40 2.3.4 Is it sufficient just to know about the onset times? . 41 2.4 Temporal Perception . -

The Haec Dies Gradual the Formulas and the Structure Pitches

68 The Haec dies Gradual The formulas and the structure pitches The primary structure pitches for recitation and accentuation are A (the Final of the mode) and C (the Dominant and a universal structure pitch). Punctuation occurs: 1) on A (the Final); 2) on C (the Dominant and universal structure pitch); 3) on F (the other universal structure pitch) and 4) on D (as a suspended cadence on the fourth above the Final). The first phrase (unique to this gradual): The structure pitches: -cc6côccc8cccc8ccccccccccc6ccccc Haec di- es, The initial structure pitch A is given a great deal of emphasis, both by the large Uncinus in Laon 239 and by the t (tenete = lengthen, hold) in the Cantatorium of St. Gall. It is followed by a rapidly moving ornament that circles the A much like the motion of a softball pitcher, in order to add momentum and intensity to the final A before ascending to C. The ornament ends with an Oriscus on the final A that builds the intensity even further until it reaches the C, the 69 climax of the entire melodic line over the word Haec. The tension continues over the accented syllable of the word di-es by means of the rapid, triple pulsation of the C, the Dominant of the piece. The melody then descends to A (the Final of the piece) and becomes a rapid alternation between A and G that swings forcefully to the last A on that syllable. The A is repeated for the final syllable of the word to produce a simple redundant cadence. -

Singing the Prostopinije Samohlasen Tones in English: a Tutorial

Singing the Prostopinije Samohlasen Tones in English: A Tutorial Metropolitan Cantor Institute Byzantine Catholic Metropolia of Pittsburgh 2006 The Prostopinije Samohlasen Melodies in English For many years, congregational singing at Vespers, Matins and the Divine Liturgy has been an important element in the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches of Southwestern Ukraine and the Carpathian mountain region. These notes describes one of the sets of melodies used in this singing, and how it is adapted for use in English- language parishes of the Byzantine Catholic Church in the United States. I. Responsorial Psalmody In the liturgy of the Byzantine Rite, certain psalms are sung “straight through” – that is, the verses of the psalm(s) are sung in sequence, with each psalm or group of psalms followed by a doxology (“Glory to the Father, and to the Son…”). For these psalms, the prostopinije chant uses simple recitative melodies called psalm tones. These melodies are easily applied to any text, allowing the congregation to sing the psalms from books containing only the psalm texts themselves. At certain points in the services, psalms or parts of psalms are sung with a response after each verse. These responses add variety to the service, provide a Christian “pointing” to the psalms, and allow those parts of the service to be adapted to the particular hour, day or feast being celebrated. The responses can be either fixed (one refrain used for all verses) or variable (changing from one verse to the next). Psalms with Fixed Responses An example of a psalm with a fixed response is the singing of Psalm 134 at Matins (a portion of the hymn called the Polyeleos): V. -

Music for a While’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

H Purcell: ‘Music for a While’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances Henry Purcell (1659–95) was an English Baroque composer and is widely regarded as being one of the most influential English composers throughout the history of music. A pupil of John Blow, Purcell succeeded his teacher as organist at Westminster Abbey from 1679, becoming organist at the Chapel Royal in 1682 and holding both posts simultaneously. He started composing at a young age and in his short life, dying at the early age of 36, he wrote a vast amount of music both sacred and secular. His compositional output includes anthems, hymns, services, incidental music, operas and instrumental music such as trio sonatas. He is probably best known for writing the opera Dido and Aeneas (1689). Other well-known compositions include the semi-operas King Arthur (1691), The Fairy Queen (1692) (an adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and The Tempest (1695). ‘Music for a While’ is the second of four movements written as incidental music for John Dryden’s play based on the story of Sophocles’ Oedipus. Dryden was also the author of the libretto for King Arthur and The Indian Queen and he and Purcell made a strong musical/dramatic pairing. In 1692 Purcell set parts of this play to music and ‘Music for a While’ is one of his most renowned pieces. The Oedipus legend comes from Greek mythology and is a tragic story about the title character killing his father to marry his mother before committing suicide in a gruesome manner. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Component 1 Appraising Music

AS Level MUSIC 7271 Mark scheme Specimen 2017 Version 1.0 aqa.org.uk Copyright © 2015 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved. AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (registered charity number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number 3644723). Registered address: AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX Mark schemes are prepared by the Lead Assessment Writer and considered, together with the relevant questions, by a panel of subject teachers. This mark scheme includes any amendments made at the standardisation events which all associates participate in and is the scheme which was used by them in this examination. The standardisation process ensures that the mark scheme covers the students’ responses to questions and that every associate understands and applies it in the same correct way. At preparation for standardisation each associate analyses a number of students’ scripts. Alternative answers not already covered by the mark scheme are discussed and legislated for. If, after the standardisation process, associates encounter unusual answers which have not been raised they are required to refer these to the Lead Assessment Writer. It must be stressed that a mark scheme is a working document, in many cases further developed and expanded on the basis of students’ reactions to a particular paper. Assumptions about future mark schemes on the basis of one year’s document should be avoided; whilst the guiding principles of assessment remain constant, details will change, depending on the content of a particular examination paper. Further copies of this mark scheme are available from aqa.org.uk. -

Liturgical Music: the Western Tradition

Liturgical Music: the Western Tradition Theologically, the West espoused the same basic idea regarding church music as the East: the words are most important, and the music must not distract too much from the meaning of the words but enhance it. The use of musical instruments Theoretically, the use of instruments had to be be curbed (due to its association with paganism: cf. Aelred of Rivaux’s opinion [Bychkov, “Image and Meaning”]). However, it was never considered unacceptable. Since 9-10th centuries, some instruments, such as the flute and lute, were used. Organs were used only in large cathedrals. In 14-15th centuries other instruments were used (such as the trumpet), but no large orchestras. From 16-17th centuries onwards we have larger bands of instruments used in churches. The use of instruments was usually reserved for great occasions and solemn Masses. Development of Western chant. Polyphony Plainchant (“Gregorian” chant) The earliest and simplest chants, still in use today, consist of one line of melody or one voice (monophonic, monody). The only way to elaborate such a chant is by holding individual notes for a longer period of time and ornamenting them by various melodic patterns (melisma, melismatic singing). Website example: Gradual, Easter Mass; early French music (11th c.) 31 Organum style polyphony The main principle of polyphony (many-voiced musical texture) is the addition of at least one other line of melody, or voice, that can be lower or higher than the main voice. In the organum style, the lower voice slowly chants a melody consisting of very long notes, while the upper voice provides elaboration or ornamentation. -

Melisma Melisma String of Several Notes Sung to One Syllable

P Tagg: Entry for EPMOW — melisma melisma string of several notes sung to one syllable. Melismatic is usually opposed to syllabic, the latter meaning that each note is sung to a different syllable. Melismatic and syllabic are used relatively to indicate the general character of a vocal line in terms of notes per syllable, some lines being more melismatic, others more syllabic. A sequence of notes sung staccato to the same syllable, for instance ‘oh - oh - oh - oh - oh’ in Peggy Sue (Holly 1957) or Vamos a la Playa (Righeira 1983), does not constitute a melisma be- cause each consecutive ‘oh’ is articulated as if it were a separate syllable (staccato = detached, cut up). A melisma is therefore always executed legato, each constituent note joined seamlessly to the preceding and/or subsequent one (legato = joined). Since inhalation before the start of a new phrase constitutes a break in the melodic flow, no melisma can last longer than the duration of one vocal exhalation. Since several notes are sung to one syllable within the duration of one musical phrase, long note values are uncommon in melismas. Melismatic singing differs more radically than syllabic singing from everyday speech in that it is uncommon to change pitch even once, let alone several times, within the duration of one spo- ken syllable. When such spoken pitch change does occur in English, for instance a quick de- scending octave portamento on the word ‘Why?’, it tends to signal heightened emotion. Together with the general tendency to regard melody as a form of heightened speech transcend- ing the everyday use of words (see MELODY §1.2), it is perhaps natural that melismatic singing is often thought to constitute a particularly emotional type of vocal expression. -

The Influence of Interactions Between Music and Lyrics: What Factors Underlie the Intelligibility of Sung Text?

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 9, No. 1, 2014 The Influence of Interactions Between Music and Lyrics: What Factors Underlie the Intelligibility of Sung Text? JANE GINSBORG Centre for Music Performance Research, Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester, UK ABSTRACT: This document provides a brief commentary on Johnson, Huron and Collister’s (2014) article entitled “Music and lyrics interactions and their influence on recognition of sung words: An investigation of word frequency, rhyme, metric stress, vocal timbre and repetition priming.” The commentary is written from the point of view of someone who is not only a fellow researcher in the field, but also a former professional singer and singing teacher. It begins by summarizing a previous study by two of the authors and the research of two further teams of investigators in the field. It concludes by focusing on each of the authors’ eight hypotheses, findings and discussion in turn. Submitted 2013 June 13; accepted 2013 July 22. KEYWORDS: singing, words, recognition, commentary THE study reported by Johnson, et al. (2014) is a follow-up to Collister and Huron’s (2008) investigation of the intelligibility of sung text in English. To summarize the background to that study, Smith and Scott (1980) and Benolken and Swanson (1990) reported that listeners find it hard to distinguish between different vowels when sung at high pitch by a trained soprano. Hollien, Mendes-Schwartz and Nielsen (2000) showed that even voice teachers, phoneticians and speech pathology students found it hard to identify vowels correctly when trained singers – male as well as female – sang too high, i.e. -

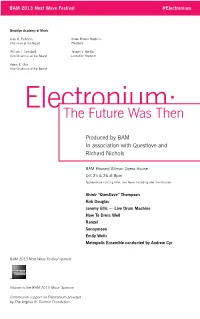

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

Note, Pitch, Scale, Melody, Harmony, Chord, Score, Orchestration, Instrumentation, Overture, Aria, Recitative, Finale, Beat, Pulse, Octave

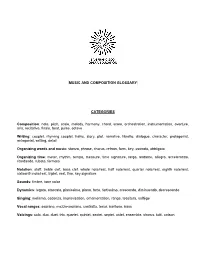

MUSIC AND COMPOSITION GLOSSARY CATEGORIES Composition: note, pitch, scale, melody, harmony, chord, score, orchestration, instrumentation, overture, aria, recitative, finale, beat, pulse, octave Writing: couplet, rhyming couplet, haiku, story, plot, narrative, libretto, dialogue, character, protagonist, antagonist, setting, detail Organizing words and music: stanza, phrase, chorus, refrain, form, key, ostinato, obbligato Organizing time: meter, rhythm, tempo, measure, time signature, largo, andante, allegro, accelerando, ritardando, rubato, fermata Notation: staff, treble clef, bass clef, whole note/rest, half note/rest, quarter note/rest, eighth note/rest, sixteenth note/rest, triplet, rest, fine, key signature Sounds: timbre, tone color Dynamics: legato, staccato, pianissimo, piano, forte, fortissimo, crescendo, diminuendo, decrescendo Singing: melisma, cadenza, improvisation, ornamentation, range, tessitura, solfège Vocal ranges: soprano, mezzo-soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, bass Voicings: solo, duo, duet, trio, quartet, quintet, sextet, septet, octet, ensemble, chorus, tutti, unison DEFINITIONS accelerando: gradually becoming faster allegro: quick tempo, cheerful andante: moderate tempo antagonist: the chief opponent of the protagonist in a drama aria: lyric song for solo voice with orchestral accompaniment, generally expressing intense emotion baritone: a male singer with a middle tessitura bass: a male singer with a low tessitura bass clef: a symbol placed at the beginning of the lower staff to indicate the pitch of the notes -

Elements of Music

GCSE Music DR SMITH Definitions Elements of Music & Listening and Appraising Support DR SMITH Definitions D Dynamics – Volume in music e.g. Loud (Forte) & Quiet (Piano). Duration – The length of notes, how many beats they last for. Link this to the time signature and how many beats in the bar. R Rhythm – The effect created by combining a variety of notes with different durations. Consider syncopation, cross rhythms, polyrhythm’s, duplets and triplets. S Structure – The overall plan of a piece of music e.g Ternary ABA and Rondo ABACAD, verse/chorus. M Melody – The effect created by combining a variety of notes of different pitches. Consider the movement e.g steps, skips, leaps. Metre – The number of beats in a bar e.g 3/4, 6/8 consider regular and irregular time signatures e.g. 4/4, 5/4. I Instrumentation – The combination of instruments that are used, consider articulation and timbre e.g staccato, legato, pizzicato. T Texture – The different layers in a piece of Music e.g polyphonic, monophonic, thick, thin. Tempo – The speed of the music e.g. fast (Allegro), Moderate (Andante), & slow (Lento / Largo). Timbre – The tone quality of the music, the different sound made by the instruments used. Tonality – The key of a piece of music e.g Major (happy), Minor (sad), atonal. H Harmony – How notes are combined to build up chords. Consider concords and discords. Elements of Music – Music Vocabulary Dynamics - Volume Fortissimo (ff) – Very loud Forte (f) – Loud Mezzo Forte (mf) – Moderately loud Mezzo Piano (mp) – Moderately quiet Piano (p) – Quiet Pianissimo (pp) – Very quiet Crescendo (Cresc.) - Gradually getting louder Diminuendo (Dim.) - Gradually getting quieter Subito/Fp – Loud then suddenly soft Dynamics - Listening Is the music loud or quiet? Are the changes sudden or gradual? Does the dynamic change often? Is there use of either a sudden loud section or note, or complete silence? Is the use of dynamics linked to the dramatic situation? If so, how does it enhance it? Duration/Rhythm (length of notes etc.) Note values e.g.